Petit Palais

14 November 2023 to 14 April 2024

After Romantic Paris, 1815-1858 and Paris 1900, City of Entertainment, the Petit Palais is devoting the last section of its trilogy to Modern Paris, 1905-1925. From the Belle Époque to the Roaring Twenties, Paris continued, more than ever before, to attract artists from all around the world. This cosmopolitan city was both a capital where innovation thrived and a place of tremendous cultural influence. Paris would maintain this status despite the reorganization of the international scene following the First World War, a period during which women played a major role, which has too often been forgotten.

Ambitious, unique, and exciting, this exhibition aims to demonstrate the dynamism of the period by highlighting the ruptures and brilliant advances that occurred, both artistic and technological. It brings together almost four hundred works by Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Marie Laurencin, Fernand Léger, Tamara de Lempicka, Jacqueline Marval, Amedeo Modigliani, Chana Orloff, Pablo Picasso, Marie Vassilieff, and many others. It also features clothing designs by Paul Poiret and Jeanne Lanvin, jewellery by Cartier, a plane from Le Bourget Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace, and even a car on loan from the Musée national de l’Automobile in Mulhouse. Through fashion, cinema, photography, painting, sculpture, and drawing, as well as dance, design, architecture, and industry, this exhibition showcases the rich creativity of the period 1905-1925.

The exhibition, organized both chronologically and thematically, draws its originality from the geographical perimeter on which it mainly focuses, i.e., the Champs-Élysées, halfway between the districts of Montmartre and Montparnasse. Stretching from the Place de la Concorde to the Arc de Triomphe and the Esplanade des Invalides, it encompasses the Petit and Grand Palais, as well as the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, and rue de la Boétie. This district was a veritable cradle and hub of Modernity. At the time, the Grand Palais hosted the latest in artistic creation at the Salon d’Automne and Salon des Indépendants every year, where the public could discover works by Douanier Rousseau, Henri Matisse, and Kees van Dongen amongst others.

During the First World War, the Petit Palais played an important patriotic role, exhibiting works of art that had been damaged during the conflict, as well as Mimi Pinson cockade (tricolour rosette) competitions. In 1925, it hosted the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, displaying an exciting mix of traditional, Art Deco, and international avant-garde productions. A few steps away, on the current-day Avenue Franklin Roosevelt, at that time called the Avenue d’Antin, the great fashion designer Paul Poiret moved into a sumptuous private mansion in 1909. He soon earned a reputation for his lavish costume parties, such as “The Thousand and Second Night” held there in 1911, for which the designer created outfits and matching accessories. His mansion also housed the Galerie Barbazanges, where Picasso’s Young Ladies of Avignon was exhibited for the first time in 1916. The Spanish artist lived on the nearby rue de la Boétie with his wife Olga. The exhibition also offers an insight into the interiors of their home, allowing an unprecedenteglimpse into the couple’s private life. After the war, the Galerie Au Sans Pareil on the Avenue Kléber opened its doors to Dada and Surrealist art. On the Avenue Montaigne, the Théâtre des ChampsÉlysées, which had opened in 1913, hosted ballet productions by the Russian, and later Swedish Ballet Companies up until 1924, with works like Relâche and The Creation of the World.

![]()

Kees van Dongen, Josephine Baker, 1925. Indian ink and watercolour on paper, on deposit at the Musée Singer Laren, Meerhout. © ADAGP, Paris 2023. Photo © AKG images.

In 1925, Josephine Baker, newly arrived in Paris, caused a sensation there with the Revue nègre. She frequented cabarets like Le Boeuf sur le Toit which opened in 1922 on the rue Boissy d’Anglas and where Jean Cocteau attracted many of the capital’s socialites. This history of “Modern Paris” is not linear; it was instead marked by numerous “accidents” and dramatic events. The scandals that punctuated artistic life are touched upon here: from the “wild beasts’ cage” (cage aux fauves) and the “Kubism” of Braque and Picasso to the highly erotic Nijinsky performing as a faun in The Rite of Spring, produced by the Ballets Russes in 1913, to the ballet Parade created by Cocteau during the war, with costumes designed by Picasso, of which some may be seen here.

Modernity assimilated all these scandals with many of them becoming key stages in the consecration of certain artists. Modernity also involved progress in the fields of technology and industry. Speed was of the essence with the development of bicycles, automobiles, and airplanes, to which trade fairs were dedicated at the Grand Palais.

This exhibition, which features an airplane and a Peugeot car, shows how the popularity of such fairs with artists like Marcel Duchamp and Robert Delaunay had a lasting influence on their work. The war also saw photographs flood the press. The development of cinema, machinery, and speed transformed society and Paris into an urban spectacle, akin to the one presented at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Fernand Léger’s Ballet Mécanique, in 1924. The role of women during this period is highlighted throughout the exhibition.

From 1905 to 1925, French society experienced dramatic social upheavals. Women enjoyed a greater sense of freedom by doing away with the corset. Artists like Marie Laurencin, Sonia Delaunay, Jacqueline Marval, Marie Vassilieff, and Tamara de Lempicka held an important place in the avant-garde. A symbol of female emancipation, the figure of the flapper was immortalized in Victor Margueritte’s novel in 1922.

With her short stature and slim waist, Josephine Baker was the embodiment of this freedom. A biracial woman from St. Louis in the United States, she experienced terrible racial riots as a child, and upon her arrival in France, marvelled at the possibility of being served in a café on the Champs-Élysées like everyone else. Paris became her city, and France, her country of adoption. Josephine Baker was just one figure in a growing multicultural movement within French society. Aïcha Goblet for example, a renowned artists’ model of West Indian origin, was immortalized in works by Félix Vallotton.

The ballroom on the rue Blomet was a popular venue for Biguine (Martiniquanstyle) music. From the underground arts scene to elite social circles, well-known figures like Max Jacob and Gertrude Stein strove to build bridges: poor artists rubbed shoulders with the rich in Montparnasse, and the luckiest amongst them attracted the attention of generous patrons such as Chaïm Soutine or American billionaire Albert Barnes. A beacon for artists and tourists from all over—Eastern Europe, Brazil, the United States, and Russia—Paris was truly the “international capital of the world”.

The scenography designed by Philippe Pumain immerses visitors in this fascinating epoch, punctuated by a selection of films by René Clair, Fernand Léger, and Charlie Chaplin.

Curators: Annick Lemoine, Director and Head Curator of the Petit Palais Juliette Singer, Chief Heritage Curator, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Petit Palais

Section 1 – Montmartre and Montparnasse, hubs of creation

At the beginning of the 20th century, artists’ studios were mainly located in Montmartre, and later in Montparnasse. Located on the fringes, these neighbourhoods offered artistic bohemians a lively setting. The public space, with its cafés and community networks, held an important place. Since the late 19th century onwards, Montmartre had attracted “rapins” or budding artists. Coming from Paris or other regions of France, as well as Spain and Italy, they moved into inexpensive studios: those at the Bateau-Lavoir welcomed, from 1904 onwards, the “Picasso Gang”. A laboratory of modernity, this collective studio was a hub of impassioned aesthetic and artistic discussions. The regular meeting place was the Lapin-Agile Cabaret, where artists mingled with poets and writers, as well as the worst types of “villainous scoundrels”.

Incessant construction, a lack of safety, the emergence of tourism, and increasing rents gradually pushed these artists to leave Montmartre for Montparnasse, on the Left Bank of the Seine.

Section 2 – The Parisian Salons at the heart of the artistic sphere

The famous artistic exhibitions that were the Parisian Salons were the heirs to an academic tradition and remained essential events for the arts world of the early 20th century. Organized by artists’ societies, these salons had always been open to women. A place where artworks were sold and presented to the public and amateurs, they were of great importance to artists. Founded in 1884, the Salon des artistes indépendants offered a counterpart to the Salon des artistes français, which exhibited official trends. Established in 1903, the Salon d’Automne was held at the Petit Palais, before moving to the Grand Palais the following year. Its objective was to provide opportunities for young artists, and to showcase new trends to the general public. As early as 1905, it caused controversy with the presentation of Fauvist works, and by exhibiting the Neo-Impressionists, as well as the Cubists, it may be said to have accompanied the birth of Modern art.

Section 3 – The growing popularity of bicycle, automobile, and aviation fairs

The new and emerging modes of transport — the velocipede, automobile, and aviation — would soon have their own fairs in Paris. In 1901, the Grand Palais hosted the International Automobile, Bicycle, and Sports Exhibition, which was subsequently held every year, except in 1909 and 1911. Visitors flocked there in the hundreds of thousands to discover Serpollet automobiles, the first Renault car, and many other vehicles. In 1908, a small part of the fair was devoted to airplanes and balloons. The public could admire Clément Ader’s airplane, as well as Levavasseur’s Antoinette and Santos-Dumont’s Demoiselle. The success was such that a new fair specially dedicated to aviation was created. The first International Exhibition of Air Navigation was inaugurated in 1909 by the President of the Republic Armand Fallières.

![]()

Pablo Picasso, Bust of a Woman or a Sailor (Study for The Young Ladies of Avignon), Paris, 1907. Oil on card, 53.5×36.2 cm. Musée national Picasso, Paris.© Succession Picasso 2023. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris)/

Section 4 – “Poiret the Magnificent”

The son of a draper, Paul Poiret founded his own fashion house in 1903, at a very young age. History recounts that he “liberated” women from corsets in 1906. Above all, he provided a certain freedom of movement to his models, while taking inspiration from Fauvist artists and oriental aesthetics. A “marketing” genius, he invented the concept of derivative products, launching the first designer perfume in 1911. That same year, he established the Maison Martine, which manufactured decorative art items designed by young and creative apprentices, based on the model of the Viennese workshops, such as the Wiener Werkstätte. Strengthening his reputation thanks to the “stars” of the day, including actresses Réjane and Mistinguett, he quickly understood the importance of using the new media of film, the press, and photography to promote his designs. He was also amongst the first couturiers to open a premises on the Champs-Élysées. In his private mansion, he organized lavish themed parties, where guests wore fancy dress.

Section 5 – The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées opens!

When it opened in 1913, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées was at the cutting edge of modernity. Built by Auguste and Gustave Perret, the building in reinforced concrete combined innovative materials and technologies with a refined aesthetic, foreshadowing art deco. The sculptor Antoine Bourdelle designed the decoration of the facade and oversaw the theatre’s interior decoration. Different artists played a role, including Maurice Denis, Édouard Vuillard, and Jacqueline Marval.

An exciting programme was inaugurated by the Russian Ballet Company (Ballets russes), founded by Serge Diaghilev, and whose star dancer was Vaslav Nijinsky. On 29 May 1913, to the music of Igor Stravinsky, the troupe shocked the public and critics alike with The Rite of Spring, adding to the renown of the work and the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées itself. These colourful Russian ballets, whose costumes were often inspired by traditional Russian folklore, were extremely popular, and influenced both fashion and jewellery of the time.

Section 6 – France at war

On 3 August 1914, Germany declared war on France. The lives of an entire nation were turned upside down: 72 million men were mobilized, and many experienced the horrors of the trenches. This war would be one of the deadliest in history, with almost 10 million killed and over 21 million injured. In Paris, taxis played a key role, transporting soldiers to the Front to the First Battle of the Marne. The Grand Palais served as a barracks, then as a military hospital, dependent on the Val-de-Grâce. It welcomed crippled soldiers and treated the disfigured, victims of a scientific and modern war that made use of new weapons. For the first time ever, war was filmed and photographed: the images from the Front, broadcast in Paris, contradicted those of propaganda campaigns.

Targeted by zeppelins (German-made airships), enemy planes, and cannons, Parisian civilians were not spared. Women worked as nurses or replaced men in vacant positions, and earned their living, amongst other places, in arms factories, where they were paid half as much as men. Many children, sometimes also forced to work, became orphans or “wards of the State”.

Section 7 – Far from the Front, life goes on

Parisian cultural life came to an abrupt halt when the capital was declared in a state of siege in August 1914. It gradually resumed in late 1915. The association Lyre and Palette organized readings and concerts, but also hosted the first French exhibition of African and Oceanian art, in November 1916, in the studio of painter Émile Lejeune. In Paul Poiret’s home, the Galerie Barbazanges presented “Modern Art in France” in July 1916, an exhibition organized by André Salmon. In it, Picasso exhibited his Young Ladies of Avignon for the first time.

The following year, an exhibition devoted to Amedeo Modigliani at the Galerie Berthe Weill had to be partly dismantled for “indecent exposure”, as his Nudes displayed hair on certain parts of the body! Theatres and performance halls also gradually reopened, and the public frequented cinemas in search of entertainment. With the representations of the ballet Parade in 1917 at the Théâtre du Châtelet, paradoxically, this period was a time of cultural effervescence and major artistic innovation.

Section 8 – Montparnasse: international melting pot

The return of peace saw the arrival of the so-called “Roaring Twenties”, characterized by intense artistic, social, and cultural activity. Coming from all over the world, myriads of artists flocked to Montparnasse. They formed what critic André Warnod called in 1925, the École de Paris (Paris School). Salons, galleries, art dealers, and free academies emerged. Cafés became meeting and exhibition spaces. Artists, Chaïm Soutine and Tsuguharu Foujita, enjoyed great success. Kiki of Montparnasse was the muse of this 1920s’ Paris that never slept, which saw the appearance of the first dance halls. Jazz was largely imported by Americans, many of whom had come to Europe to escape Prohibition, then in full swing at home. Some of them also fled American Segregationist laws.

Balls sprung up all over the city and cemented the sense of an artistic community. The Bal colonial (Colonial Ball) — later called the “Bal nègre” — was also a highlight of Parisian nightlife, with its Martinican biguine music.

Section 9 – Paris “faster, higher, stronger”

From 1920 to 1929, the Roaring Twenties celebrated a newfound peace coupled with a great thirst for life. The generation that had experienced the turmoil and conflicts of the Great War sought oblivion through alcohol and debauchery. They nonetheless contributed to making Paris into a kind of Eden, as Ernest Hemingway depicted in his novel A Moveable Feast (1964). Clothes reflected this novel art of living: cocktail dresses, sequins, and feathers were ideal for the new style of frenzied dancing. Dances too had accelerated, at a time when speed was embodied in everything new: from jazz and the Charleston from across the Atlantic, to the cinema, automobiles, trains, liners, etc. The ambivalent figure of the “flapper” appeared in this context. This “new woman”, with multiple facets, was both fascinating and disturbing. Depicted as a heroine by Victor Margueritte, she spread through literature and won over the female press, advertising, and the cosmetics industry.

Section 10 – The Swedish Ballets and La Revue nègre des ChampsÉlysées

In 1920, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées renewed its repertoire with the Swedish Ballets, under the patronage of collector Rolf de Maré. He designed these performances as a total work of art showcasing his own collection. The choreography was created by Swedish dancer Jean Börlin up until 1925. Exploring the relationships between stage and painting, Börlin pushed the limits of dance in its interactions with the visual arts. The composers of the group Les Six (Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc, Germaine Tailleferre), gathered around Jean Cocteau, participated in certain seasons, as did artists Marie Vassilieff and Fernand Léger.

After the departure of the Swedish Ballets, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées hosted La Revue nègre in October 1925. Coming from the United States, the young Josephine Baker caused a sensation with her thrilling dance style. She was welcomed in Paris in a society free from segregation laws. She would later adopt France as her homeland.

Section 11 – The International Exhibition of Decorative Arts, 1925

Postponed three times, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts opened its doors on 28 April 1925. By the time it closed on 25 October, it had welcomed over 15 million visitors and met with immense popular success. This large-scale event was held from the Place de la Concorde to the Pont de l’Alma and extended from the Champs-Élysées roundabout to the Esplanade des Invalides, via the Alexandre-III Bridge. It brought together twenty-one nations–despite the absence of both Germany and the United States–represented by one hundred and fifty galleries and ephemeral pavilions, including the Grand Palais. Its importance was both economic and cultural. The aim was to promote the excellence of French traditions, in the face of a defeated Germany and international competition. It was also essential to revive industrial production and the luxury goods industry, in a France crippled by inflation. Dedicated to art, decoration, and modern life, this great celebration, sometimes considered the swan song of a luxury aesthetic, marked the appearance of the expression “art deco”. This style would have a global influence, from Asia to Oceania to the Americas, with Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro, the largest art deco sculpture in the world.

![]()

Paul Colin, Poster for La Revue nègre at the Champs-Élysées music hall, c. 1925. © ADAGP, Paris 2023 Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Blérancourt) / Gérard Blot. Modern Paris – 14 November 2023 to 14 April 20249 Press Visuals 1.

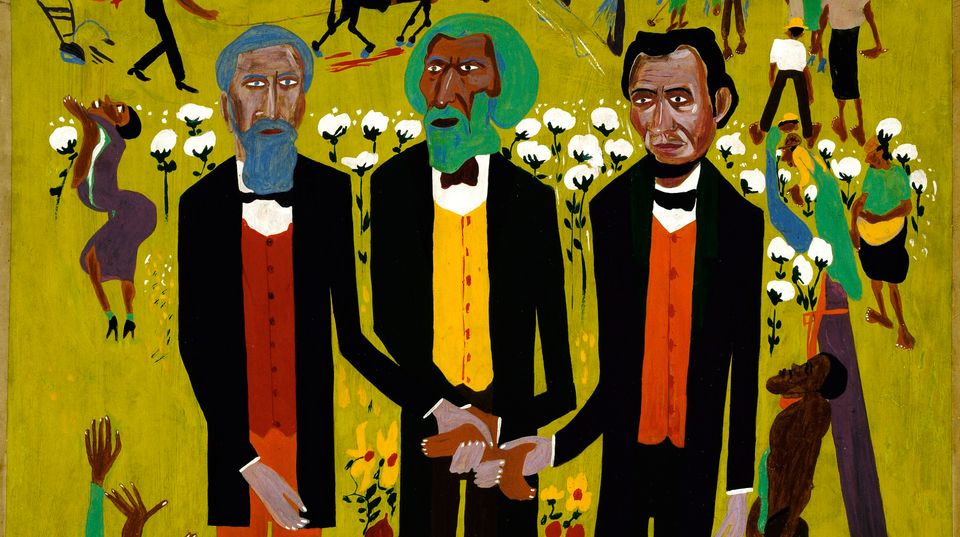

At the Bateau-Lavoir, Picasso painted The Young Ladies of Avignon, a major turning point in his work. The final composition focuses on five massive female nudes, while the studies and preparatory sketches also included male figures. The bodies are violently abbreviated, constructed using large geometric lines. The faces are simplified and marked with hatching. The work breaks away from Western tradition and heralds the Cubist revolution. It made headlines with its obvious eroticism and references to African art.

Once nicknamed a “Jack of all trades” (“Jack of all trades, master of none”), Marie Vassilieff was a key figure of “Montparnos”. Her Scipio Africanus challenged the codes of portraiture and was inspired by Picasso’s formal deconstructions. The use of Black models and the pioneering valorisation of the Other were constants in the painter’s work. Here, the odalisque with the obelisk, which pays tribute to Vassilieff’s African domestic worker, is also a daring variation on the masculinefeminine gender binary.

Objects from Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania provided artists with novel plastic solutions in line with their quest for abstraction. Picasso, Vlaminck, and Van Dongen considered these artworks in a new light, not devoid of an element of imagination concerning their ancient origin. The arts of Africa or Oceania, however, had nothing “primitive” or archaic about them, but were instead, often quite contemporary. Some artists, such as Vlaminck, collected them, and others, even attempted to sell them.

Joachim-Raphaël Boronali, also known as Lolo the Donkey, Aliboron the Donkey, Sunset over the Adriatic, 1910. Oil on canvas, 54×81 cm. Espace culturel communal Paul Bédu, Milly-la-Forêt.

Exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1910, this sunset was painted by Joachim-Raphaël Boronali, an Italian artist laying claim to “Excessivism”. The critics’ reactions were rather positive, but the truth behind the work was soon revealed: a brush dipped in paint had been attached to the tail of a donkey. The animal’s movements smeared the canvas held behind it by the jokers. Orchestrated by writer Roland Dorgelès, this hoax was typical of the rebellious and playful spirit of Montmartre.

Henri Rousseau, also known as Douanier Rousseau, The Snake Charmer, 1907. Oil on canvas, 167×189.5 cm. Établissement public du musée d’Orsay et du musée de l’Orangerie - Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski. At the Salon d’Automne of 1905,

Douanier Rousseau exhibited The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope (Basel, Fondation Beyeler), whose lion may have indirectly inspired the term “fauve”, literally meaning “wild animal”. Two years later, he exhibited his famous Snake Charmer at the same Salon. In it, we can see a Black Eve playing music in a primitive natural setting that is as fantastic as it is disturbing, thus opening other paths to Modernity.

![]()

Gino Severini, The Pan Pan Dance, 1909-1960 (copy of the original from 1910-1911). Oil on canvas, 280×400 cm. Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Centre de création industrielle © ADAGP, Paris 2023 Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI) / Hélène Mauri.

Severini’s Pan Pan Dance was hailed by Apollinaire as “the most important work painted by a Futurist brush” (L’Intransigeant, 7 February 1912). In the middle of the canvas are two dancers in red, depicted in movement. Around them is a compact lively crowd, comprising colourful diffracted shapes. The scene appears as if seen through a kaleidoscope. The painter succeeds in conveying the animation of a joyous working-class crowd and the spirited atmosphere of certain fashionable Parisian cafés.

Robert, Delaunay, Tribute to Blériot, 1914. Oil on canvas, 46.7×46.5 cm. Musée de Grenoble. Photo © Ville de Grenoble /Musée de Grenoble / J.L. Lacroix.

After visiting the Buc Airfield, near Paris, Robert Delaunay paid tribute to the career of Blériot, a great manufacturer of biplanes, monoplanes, and military aircraft, who had also founded this airfield. Continuing his research into simultaneous contrasts, Delaunay built the painting around the motif of the propeller in motion. Its rotation creates a dynamic that radiates throughout the composition and translates the excitement of air shows.

The first International Air Transport Exhibition was held at the Grand Palais in 1909. The manufacturer and businessman Armand Deperdussin caused a sensation with his "monoplane". Hiring the services of young engineer Louis Béchereau, the Type B aeroplane exceeded 200 km/h for the first time and won the GordonBennett trophy in 1912 and 1913. Béchereau's talent survived Deperdussin's bankruptcy, and was put to good use on aircraft intended for aerial warfare.

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1913/1914. 126.5×31.5×6.5 / 53 cm (stool height) / 73 cm (wheel height) / 63.5 cm (wheel diameter), Object, metal, painted wood. Musée National d’Art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou © ADAGP, Paris 2023 © Association Marcel Duchamp Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI) / Christian Bahier / Philippe Migeat.

In 1912, Marcel Duchamp visited the 4th International Exhibition of Air Navigation with Fernand Léger and Constantin Brancusi. Fascinated by a large propeller exhibited amongst the engines and airplanes, he declared: “Painting is finished. Who could do anything better than this propeller?” and grabbed a stool to attach a wheel to it, which he made turn. The following year, he bought a bottle rack at the Bazar de l’Hôtelde-Ville department store and signed it. By elevating these “ready-made, already there” objects into works of art, he invented the concept of the ready-made.

![]()

Marie Laurencin, The Dreamer, 1910-1911 Oil on canvas, 91.7×73.2×2.5 cm. Musée national Picasso, Paris. © ADAGP, Paris 2023, Photo © RMNGrand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Adrien Didierjean © Fondation Foujita. 1

Having already covered the Balkan Wars in 1912, Georges Scott produced numerous drawings during the Great War, for the magazine L’Illustration. In this work, he provides a striking account of a shell explosion, which blows away all the soldiers in its path. An exhibition was dedicated to him at the Galerie Georges Petit in February 1915, entitled "Visions of War".

![]()

Jacqueline Marval, Patriotic Dolls, 1915. Oil on canvas, 80×70 cm. Comité Jacqueline Marval. Photo © Courtesy Comité Jacqueline Marval, Paris / Nicolas Roux Dit Buisson.

![]()

Marevna, Death and the Woman, 1917. Oil on wood, 107×134 cm. Association des Amis du Petit Palais, Geneva. Photo © Studio Monique Bernaz, Geneva

The war violently erupts in this work by Marie Vorobieff, known as Marevna, who arrived from Russia in 1912. A young woman, wearing a light dress and fishnet stockings, is concealed under a gas mask. Sitting opposite her, Death has the features of a medal-winning soldier in a horizonblue uniform. His mutilated body features prosthetic legs and hands. The black and white tiles evoke a chessboard. The scene resembles a sinister game of chess, the outcome of which is likely to be catastrophic.

Here, Kees van Dongen paints a sensual portrait of his mistress, the eccentric and wealthy Countess Luisa Casati. She appears perched on high heels, contemplating her barely veiled nudity in a mirror. A glowing skull in the darkness (on the right), contrasts with this scene, evocative of the worldly life that the painter then led with his mistress, far from the Front. As with the ancient vanitas, it reminds us that death lurks in this time of war. 23.

![]()

Madeleine Julie Goblet Oil on canvas, 100×81.5 cm. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais. With a Martinican father and a mother from mainland France, Madeleine Julie Goblet stands out by wearing a turban and adopting the oriental pseudonym Aïcha. An actress, circus, and music-hall artist, she became a “star” model in 1920s’ Paris. Painted by Jules Pascin, Moïse Kisling, Henri Matisse, and Kees van Dongen, she was also represented by Félix Vallotton, here in a style with both classical and Modern undertones.

![]()

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitsky), Black and White, 1926-1980 (print). Black and white photograph, 18×23.5 cm FRAC Bourgogne, Dijon. © ADAGP, Paris 2023 Photo © Telimages.

With her boyish haircut, upturned nose, and smooth, hairless body, Kiki (Alice Prin, her real name) was a Montparnasse legend. She was immortalized by both Foujita and Pablo Gargallo. In 1921, she became the companion and muse of American artist Man Ray, inspiring him to create works that marked the history of photography, including Black and White, for which she posed with a Baoulé mask. For Ingres’s Violin, she posed naked, shot from behind, her body transformed into a musical instrument by the addition of two f-holes positioned in the hollow of her back

![]()

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitsky), Ingres’s Violin, 1924-1977 (print). Black and white photograph, 27×20 cm. FRAC Bourgogne, Dijon. © ADAGP, Paris 2023.

![]()

Chaïm Soutine, My Bride, 1923. Oil on canvas, 91×55 cm. Établissement public du musée d’Orsay et du musée de l’Orangerie - Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée de l’Orangerie) / Hervé Lewandowski.

![]()

Amedeo Modigliani, Seated Woman with Child (Motherhood), 1919. Oil on canvas, 130×81 cm. Musée National d’Art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris on deposit at the LaM, Villeneuve-d’Ascq. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI) / Bertrand Prévost.

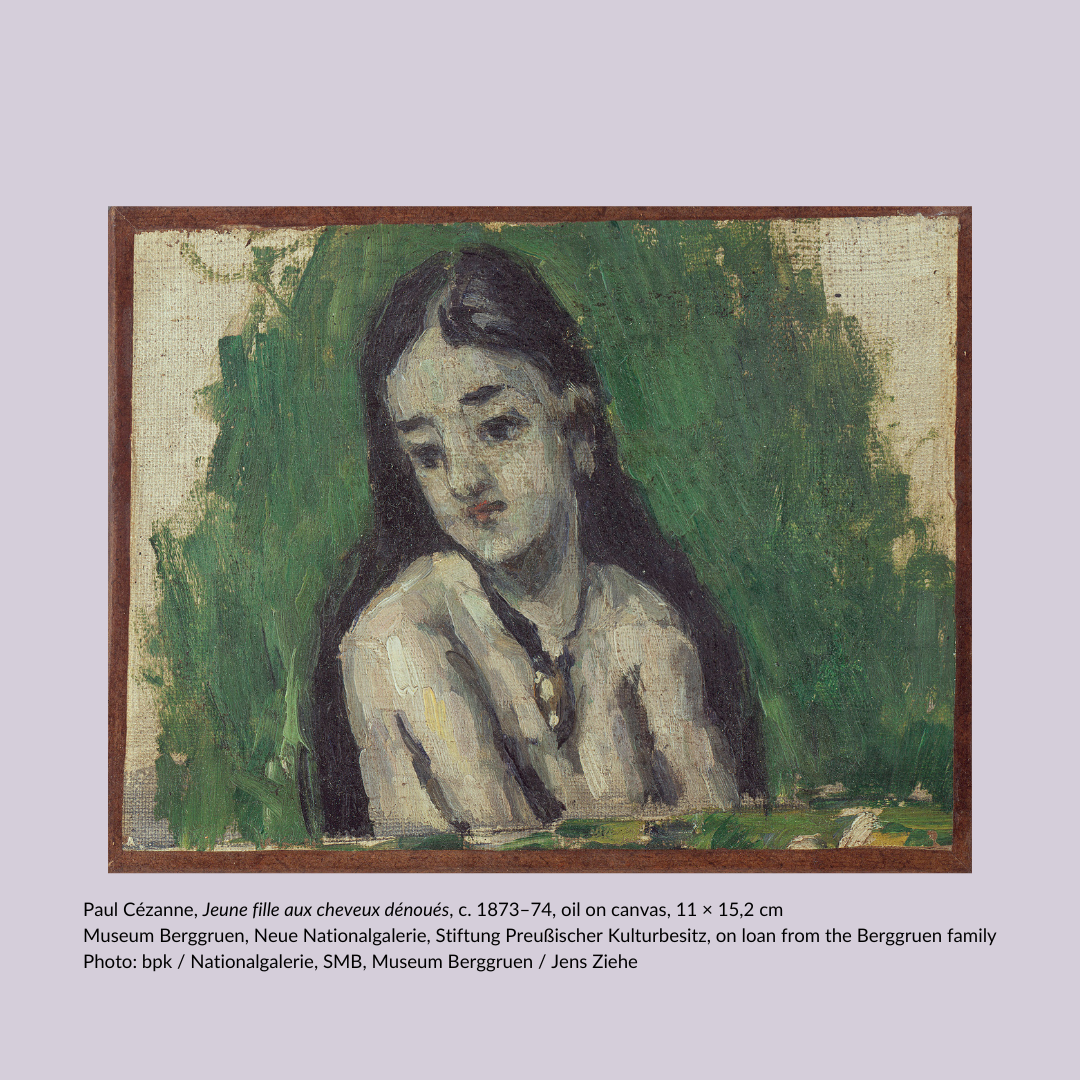

Amedeo Modigliani painted this maternal scene at a time when his partner, Jeanne Hébuterne, was pregnant with their second child. Here, he renews the classical motif of the Virgin and Child in a secular fashion, with a pyramidal composition. This painting comprised one of his largest formats, for which he made use of materials provided by Polish art dealer Léopold Zborovski. Dying at age thirty-six, a few months after completing this painting, Modigliani left behind some three hundred portraits and twenty-five sculpted figures.

Tarsila do Amaral, A Cuca, c. February 1924. Oil on canvas, 60.5×72.5 cm. CNAP/FNAC, Paris la Défense on deposit at the Musée de Grenoble. Photo © Ville de Grenoble/Musée de Grenoble JeanLuc Lacroix. © Tarsila do Amaral Licenciamento e Empreendimentos Ltda / Cnap.

![]()

Max Ernst, Aquis Submersus, 1919. Oil on canvas, 54×43.8 cm. Städel Museum, Germany. © ADAGP, Paris 2023 Photo © RMN- Grand Palais (BPK, Berlin) / Image Städel Museum.

Aquis submersus means “submerged by water” in Latin. Flanked by blind buildings, a swimming pool features the round reflection of a moon dial in its centre. The two figures seem foreign to each other: in the foreground, we see a moustachioed being with an ambiguous shape, and in the swimming pool, a bather, doing a handstand, of whom we only see the legs. Enigmatic and as if frozen in time, this composition by Max Ernst recalls the metaphysical paintings of his contemporary, Italian artist Giorgio De Chirico.

Jean Cocteau, “Write legibly” Masked SelfPortrait, 1919. Lithograph, 75×60 cm. Musée Jean Cocteau, Menton © ADAGP Paris, 2023. Photo © Musée Jean Cocteau Séverin Wunderman Collection, Menton / Serge Caussé.

![]()

Fernand Léger, Man with a Pipe, 1920. Oil on canvas, 91×65 cm. Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris. © ADAGP, Paris 2023. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais / Agence Bulloz. Modern Paris – 14 November 2023 to 14 April 202421

![]()

Tamara de Lempicka, Saint-Moritz, 1929. Oil on wood, 35×27×0.5 cm. Musée des BeauxArts d’Orléans / photo François Lauginie © ADAGP, Paris 2023 © Tamara Art Heritage.

The skier represented in this work appears almost as an archetype of the Art Deco style. With short hair and crimson lips, and a sweater borrowed from a man’s wardrobe, this modern woman, at the height of her seduction and social success, seems to emerge from the frame. Her features are a subtle combination of post-Cubism and Neoclassicism. Painted in 1929 for the cover of a magazine, the image can be said to embody the ascent of the “flapper” climbing the snowy peaks: skiing had only recently become a resort sport associated with the values of Modernity.

Born in St Louis, Missouri, Freda Josephine McDonald (1906-1975) worked as a maid as a child. She made a name for herself in music hall thanks to her flexible footwork and sense of burlesque. Biracial, she appeared as “White” or “Black” depending on the show. Spotted at the Plantation Club in New York, she joined La Revue nègre in Paris. The young dancer that can be seen in Paul Colin’s poster was inspired by a drawing by Miguel Covarrubias published in Vanity Fair and Josephine Baker was very quickly associated with this “Jazz Baby” figure.

Robert Delaunay, Paris – Die Frau und der Turm (The City of Paris – The Woman and the Tower), 1925. Oil on canvas, 52.5×207.5 cm. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. Photo © BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image Staatsgalerie Stuttgart.

To decorate the Pavilion of the Society of Decorative Artists, Robert Delaunay painted an immense Eiffel Tower measuring four and a half meters high, of which The Woman and the Tower constitutes a smaller version. Surrounded by factories, the Concorde Obelisk, and the roundabout at the Champs-Élysées, the Tower is painted here in bright colours. Represented from a low but dynamic angle, it was both the emblem of Paris and Modernity. In total, the artist dedicated over fifty paintings to the Eiffel Tower from 1911 onwards. According to him, “the Tower speaks to all humanity”.

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

,%20detail%20uit%20rechterdeel%20.jpg)

.jpg?mode=max)

,%202000.JPG)

,%202000.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)

.jpeg/564px-Zacharie_Astruc_-_Femme_endormie%2C_dans_un_int%C3%A9rieur_artistique_(sc%C3%A8ne_de_somnambulisme).jpeg)