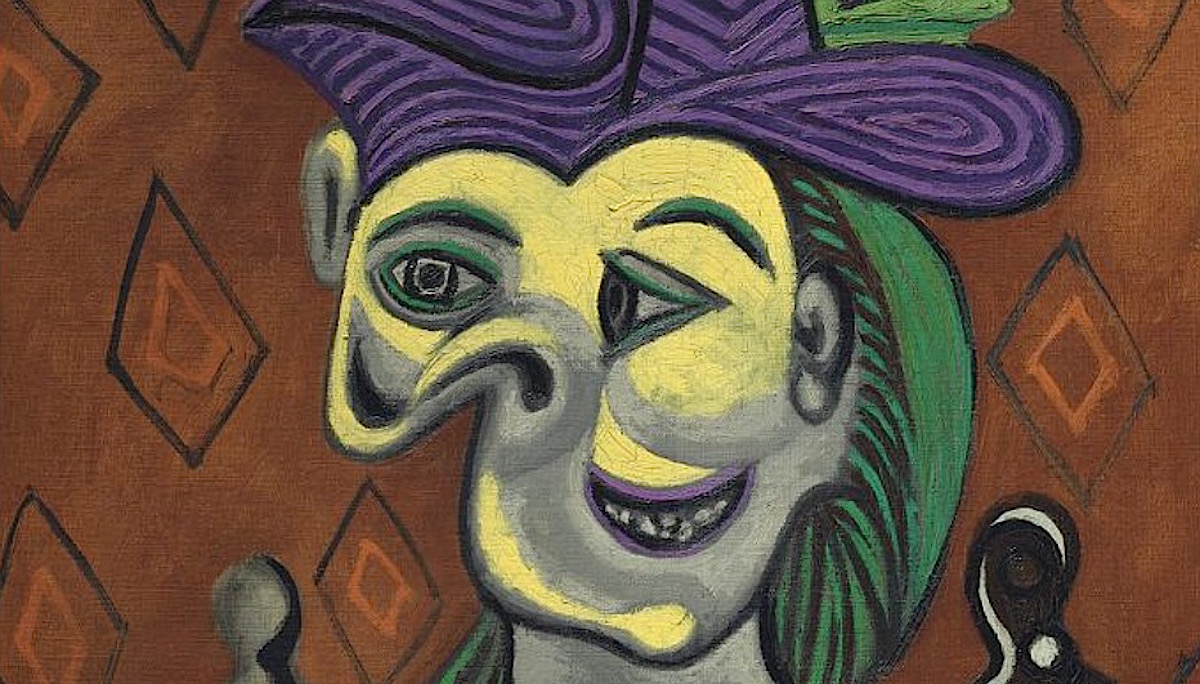

Pablo Picasso. Femme assise, robe bleue. Oil on canvas. Painted on 25 October 1939. Estimate: $35,000,000-50,000,000.

On May 15, Christie’s will offer Femme assise, robe bleue by Pablo Picasso as a highlight of its Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (Estimate: $35,000,000-50,000,000). Painted on 25 October 1939, Femme assise, robe bleue is a searing portrait of Picasso’s lover, Dora Maar. Painted on the artist's birthday just after the beginning of the World War II, the work is filled with the unique character, distortions and tension that mark Picasso’s greatest portraits of Dora; at the same time, there is a tender sensuality present in the organic, curvaceous forms of the face which provides some insight into their relationship. This picture was formerly owned by G. David Thompson, to whom the great curator and art historian Alfred H. Barr, Jr. referred as, 'one of the great collectors of the art of our time.' (A.H. Barr, Jr., 'Foreword', auction catalogue, Parke-Bernet, New York, 1966, n.p.).

Giovanna Bertazzoni, Deputy Chairman, Impressionist and Modern Art, remarked,

Dora Maar was one of Picasso's most important Muses. His affair with Dora came in the latter years of his relationship with Marie-Thérèse Walter. Marie-Thérèse had been young, blond and athletic, with a sunny disposition and a sweet character; Picasso's time with her had resulted in flowing, sensual images. Dora was a marked contrast, as is demonstrated by Femme assise, robe bleue: a complex, troubled character, intellectual and creative, a photographer and an artist in her own right. She was a sparring partner for Picasso, a challenging voice, having already been an established figure in Surreal circles by the time the pair were introduced.

Picasso often presented Dora with her signature hats that she often sported, a quality that distinguishes her among Picasso’s muses at first glance. Certainly in Femme assise, robe bleue the hat is present and correct, a striped purple confection with what appears to be a green feather or foliage of some sort. These hats often add a playful air to Picasso's paintings of Dora. They also serve as a counterbalance to the severity with which he presented her features, as is the case in the shifting, vulnerable flesh of Femme assise, robe bleue. Some critics have linked the pictures of Dora specifically to tension caused by the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War. However, it appears that Picasso, whose paintings often functioned as a barometer for his own state of mind, had found a Muse who was perfectly suited to his tense depictions of that period. It was both Dora's personality and a wider sense of unease at the situation in the world that Picasso managed to express in these bracing paintings.

On May 15, Christie’s will also offer Property from the Collection of Greta Garbo in its Evening Sale of Impressionist and Modern Art, including prime examples from artists including Jan Alexej Von Jawlensky, Chaim Soutine and Robert Delaunay. In the history of cinema, few individuals remain as enigmatic and iconic as the actress Greta Garbo. “Of all the stars who have ever fired the imaginations of audiences,” film historian Ephraim Katz wrote, “none has quite projected a magnetism and a mystique equal to [hers].”

Derek Reisfield, Greta Garbo’s great nephew, remarked:

Much of the public’s fascination with Garbo stemmed from the actress’s successful evasion of the Hollywood publicity machine. From her earliest years in film to her death in 1990, Garbo granted few interviews, declined to sign autographs, and avoided public functions such as the Academy Awards. After retiring from cinema at just thirty-five years old, the actress transitioned to a life dedicated to fine art, scholarship, and the many friends she held dear. From the 1940s, Garbo began to assemble a remarkable private collection of painting, sculpture, works on paper, and decorative art. For those fortunate enough to be welcomed into the actress’s wood-paneled Manhattan residence, the ‘real’ Garbo would be revealed: a vivacious, quick-witted woman who lived each day surrounded by beauty.

Through both personal erudition and friendships with luminaries such as the Barnes Foundation’s visionary founder Albert Barnes, and Alfred Barr, the Museum of Modern Art’s first director, Garbo steadily acquired works by a range of artists. Dynamically composed in brilliant hues, the collection was largely hidden from public view—a treasure to be absorbed through intimate contemplation and conversation.

The evening sale of Impressionist and Modern art will encompass three canvases that exemplify Garbo’s sophisticated taste and proclivity for dazzling color.

Chaïm Soutine’s Femme à la poupée, 1923-1924 (estimate: $3.5-4.5million),

![]()

Alexej von Jawlensky (1864-1941), Das blasse Mädchen mit grauen Zopfen, signed ‘A. Jawlensky’ (lower left) and signed again 'A. Jawlensky' (upper left), oil over pencil on linen-finish paper laid down on Masonite, 25 x 19 1/2 in. (63.5 x 49.5 cm.), Painted circa 1916, Estimate $1-1.5M

and Alexej von Jawlensky’s Das blasse Mädchen mit Grauen Zopfen, 1916 (estimate $1-1.5million)

Garbo’s grandniece, Gray Reisfield Horan, recalled her aunt’s profound love for the collection. “What are they talking about?” she would ask visitors about the pictures. “What do they say to each other?” It was a tremendously personal assemblage, one the actress arranged and re-hung with each new purchase. Horan described the image Garbo sitting each night in front of her favorite paintings, “enjoying her evening scotch and a Nat Sherman cigarettello… held so elegantly with her gemstone encrusted Van Cleef & Arpels holder.”

In many ways, the collection both reflected and rebutted Garbo’s illustrious career: suffused with undeniable visual power, its boldness of color stood in contrast with the argent mystique of early Hollywood. “Color,” Horan recalled of her aunt’s acquisitions, “was always the essential component…. The works meshed and flowed in a wondrous explosion of enveloping hues…. Nothing was black and white.” Garbo herself, mesmerized by Delaunay’s vibrant La femme à l’ombrelle, would often remark of the canvas, “It makes a dour Swede happy.” If Garbo managed to enchant audiences via movement and gaze, so did the artists in her collection similarly capture the viewer through their pioneering use of brushwork and palette. “Color,” she enthused, “is just the starting point. There is so much more.”

Thoughtfully assembled in New Orleans during the opening years of the twentieth century, a large portion of works have remained in the family’s collection since 1913. At that time, New Orleans was an epicenter of culture, more artistically engaged than any other city in the American South, owing to its well-established cosmopolitanism and its historical and cultural ties to France. Yet the city had only one art collector of truly national standing – the sugar magnate Hunt Henderson. The resulting collection is a world-class assemblage of avant-garde art, from Impressionism through early modernism, with the selection featured in the spring season sales to encompass works by Paul Cézanne, Honoré Daumier, Edgar Degas, Raoul Dufy, Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renior, and James McNeil Whistler expected to realize in excess of $23 million.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), La route de Vétheuil, effet de neige, oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 32 1/8 in. Painted in 1879.

Leading the collection is Claude Monet’s, La route de Vétheuil, effet de neige, painted in 1879 (estimate: $10,000,000-15,000,000). Monet painted this exquisitely subtle and delicate view of Vétheuil under heavy snow in 1879, during his first full year living in the rural hamlet about sixty kilometers northwest of Paris. This canvas is the first in a sequence of three painted from approximately the same vantage point, exploring the changes in the winter landscape over a period of days. The three years spent at Vétheuil represent a decisive moment of artistic reassessment for the Impressionist painter. It was here that Monet abandoned scenes of modern life and leisure that had dominated his earlier work and began to focus on capturing the fleeting aspects of nature, employing a nascent serial technique that laid the groundwork for his most important later production.

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), La côte Saint-Denis à Pointoise, oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 21 3/8 in. Painted circa 1877.

Also on offer will be an exemplary canvas by Paul Cézanne, La côte Saint-Denis à Pontoise, painted circa 1877 (estimate: $5,000,000-7,000,000). This landscape, which Cézanne painted during a visit with Pissarro at Pontoise, bears witness to the extraordinary creative partnership between the artist and his Impressionist mentor. Pissarro produced a view of the identical motif in the same year, the two artists very possibly setting up their easels side-by-side. The paintings both depict a cluster of red- and blue-roofed houses on the rue Vieille-de-l’Hermitage, just a short walk from Pissarro’s home. Equally significant, however, are the differences between the two artists’ interpretations of their shared motif. While Pissarro continued to work within the Impressionist idiom, Cézanne had already begun to experiment with an increasingly abstract construction of the landscape, transmuting the vagaries of the natural world into the forms of an ideal order.

Giovanna Bertazzoni, Deputy Chairman, Impressionist and Modern Art, remarked,

“Femme assise, robe bleue is an extraordinary portrait of Picasso’s great Muse and love, Dora Maar. It exhibits all of the most exhilarating qualities that Dora brought out in Picasso’s work: the striking palette, ornate headwear, and remarkable complexity conveyed by Dora’s distorted features. The rich, thick twirls of oil depicting the mass of her hair (which Picasso was mesmerised by) and the shapes of her hat convey the impetus and passion at the core of this portrait. We are bringing Femme assise, robe bleue to the market at a time when the demand for Picasso’s portraits of one of his greatest subjects, Dora Maar, is at an all-time high. The canvas is a powerful example of Picasso’s creative imagination and the passion which Dora inspired in him.”Francis Outred, Chairman and Head of Post-War and Contemporary Art, EMERI continued:

“Femme assise, robe bleue is a timeless icon of artist and muse which speaks to collectors across the centuries and continents. Coming from a major European collection, the picture holds within it an incredible story. It originally belonged to Picasso’s dealer, Paul Rosenberg but was confiscated in 1940 soon after its creation. Later in the War it was intended to be transported to Germany but was famously intercepted and captured by members of the French Resistance, an event immortalised, albeit in fictional form, in the 1966 movie The Train, starring Burt Lancaster and Jeanne Moreau. In real life, one of the people who helped to sabotage the National Socialists’ attempt to remove countless artworks from France towards the end of the war was in fact Alexandre Rosenberg. The son of Paul Rosenberg, he had enlisted with the Free French Forces after the invasion of France in 1940. The painting was subsequently owned by the Pittsburgh steel magnate and legendary collector, George David Thompson, from whose collection many works now grace the walls of museums in the United States and Europe. We fully expect the romance and power of this painting and its remarkable story to capture the hearts and minds of our global collectors of masterpieces from Old Masters to Contemporary, this May.”

Dora Maar was one of Picasso's most important Muses. His affair with Dora came in the latter years of his relationship with Marie-Thérèse Walter. Marie-Thérèse had been young, blond and athletic, with a sunny disposition and a sweet character; Picasso's time with her had resulted in flowing, sensual images. Dora was a marked contrast, as is demonstrated by Femme assise, robe bleue: a complex, troubled character, intellectual and creative, a photographer and an artist in her own right. She was a sparring partner for Picasso, a challenging voice, having already been an established figure in Surreal circles by the time the pair were introduced.

Picasso often presented Dora with her signature hats that she often sported, a quality that distinguishes her among Picasso’s muses at first glance. Certainly in Femme assise, robe bleue the hat is present and correct, a striped purple confection with what appears to be a green feather or foliage of some sort. These hats often add a playful air to Picasso's paintings of Dora. They also serve as a counterbalance to the severity with which he presented her features, as is the case in the shifting, vulnerable flesh of Femme assise, robe bleue. Some critics have linked the pictures of Dora specifically to tension caused by the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War. However, it appears that Picasso, whose paintings often functioned as a barometer for his own state of mind, had found a Muse who was perfectly suited to his tense depictions of that period. It was both Dora's personality and a wider sense of unease at the situation in the world that Picasso managed to express in these bracing paintings.

On May 15, Christie’s will also offer Property from the Collection of Greta Garbo in its Evening Sale of Impressionist and Modern Art, including prime examples from artists including Jan Alexej Von Jawlensky, Chaim Soutine and Robert Delaunay. In the history of cinema, few individuals remain as enigmatic and iconic as the actress Greta Garbo. “Of all the stars who have ever fired the imaginations of audiences,” film historian Ephraim Katz wrote, “none has quite projected a magnetism and a mystique equal to [hers].”

Derek Reisfield, Greta Garbo’s great nephew, remarked:

“Greta Garbo had a real love of art and paintings, and she was very passionate about certain artists and pictures. She was particularly enamored with these three canvases, which offer a particularly modern representation of women, especially for their time. This was a concept that that really resonated with her. Another factor that drove her collecting tastes was color. She was absolutely entranced by the vibrancy of the Delaunay. It was the central focal point of her living room in New York, and all of the furniture that she chose to surround the canvas played into its incredible colors. In essence, when we talk about Garbo we call her the first ‘modern woman,’ and I think that these three works speak to both her fundamental strength and striking aesthetic.”

Much of the public’s fascination with Garbo stemmed from the actress’s successful evasion of the Hollywood publicity machine. From her earliest years in film to her death in 1990, Garbo granted few interviews, declined to sign autographs, and avoided public functions such as the Academy Awards. After retiring from cinema at just thirty-five years old, the actress transitioned to a life dedicated to fine art, scholarship, and the many friends she held dear. From the 1940s, Garbo began to assemble a remarkable private collection of painting, sculpture, works on paper, and decorative art. For those fortunate enough to be welcomed into the actress’s wood-paneled Manhattan residence, the ‘real’ Garbo would be revealed: a vivacious, quick-witted woman who lived each day surrounded by beauty.

Through both personal erudition and friendships with luminaries such as the Barnes Foundation’s visionary founder Albert Barnes, and Alfred Barr, the Museum of Modern Art’s first director, Garbo steadily acquired works by a range of artists. Dynamically composed in brilliant hues, the collection was largely hidden from public view—a treasure to be absorbed through intimate contemplation and conversation.

The evening sale of Impressionist and Modern art will encompass three canvases that exemplify Garbo’s sophisticated taste and proclivity for dazzling color.

Robert Delaunay, La femme à l’ombrelle ou La Parisienne, oil on canvas, 48 3/8 x 35 1/2 in. (122.8 x 90.2 cm.), Painted in Paris, 1913. Estimate: $4-7million

These works include Robert Delaunay’s La femme à l’ombrelle ou La Parisienne, 1913 (estimate: $4-7million) ;Chaïm Soutine’s Femme à la poupée, 1923-1924. Estimate: $3.5-4.5million

Chaïm Soutine’s Femme à la poupée, 1923-1924 (estimate: $3.5-4.5million),

Alexej von Jawlensky (1864-1941), Das blasse Mädchen mit grauen Zopfen, signed ‘A. Jawlensky’ (lower left) and signed again 'A. Jawlensky' (upper left), oil over pencil on linen-finish paper laid down on Masonite, 25 x 19 1/2 in. (63.5 x 49.5 cm.), Painted circa 1916, Estimate $1-1.5M

and Alexej von Jawlensky’s Das blasse Mädchen mit Grauen Zopfen, 1916 (estimate $1-1.5million)

Garbo’s grandniece, Gray Reisfield Horan, recalled her aunt’s profound love for the collection. “What are they talking about?” she would ask visitors about the pictures. “What do they say to each other?” It was a tremendously personal assemblage, one the actress arranged and re-hung with each new purchase. Horan described the image Garbo sitting each night in front of her favorite paintings, “enjoying her evening scotch and a Nat Sherman cigarettello… held so elegantly with her gemstone encrusted Van Cleef & Arpels holder.”

In many ways, the collection both reflected and rebutted Garbo’s illustrious career: suffused with undeniable visual power, its boldness of color stood in contrast with the argent mystique of early Hollywood. “Color,” Horan recalled of her aunt’s acquisitions, “was always the essential component…. The works meshed and flowed in a wondrous explosion of enveloping hues…. Nothing was black and white.” Garbo herself, mesmerized by Delaunay’s vibrant La femme à l’ombrelle, would often remark of the canvas, “It makes a dour Swede happy.” If Garbo managed to enchant audiences via movement and gaze, so did the artists in her collection similarly capture the viewer through their pioneering use of brushwork and palette. “Color,” she enthused, “is just the starting point. There is so much more.”

Christie’s will also present works formerly from The Collection of Hunt Henderson, which comprises one of the earliest important groupings of Impressionist & Post-Impressionist Art privately held in the Southern region of the United States.

Thoughtfully assembled in New Orleans during the opening years of the twentieth century, a large portion of works have remained in the family’s collection since 1913. At that time, New Orleans was an epicenter of culture, more artistically engaged than any other city in the American South, owing to its well-established cosmopolitanism and its historical and cultural ties to France. Yet the city had only one art collector of truly national standing – the sugar magnate Hunt Henderson. The resulting collection is a world-class assemblage of avant-garde art, from Impressionism through early modernism, with the selection featured in the spring season sales to encompass works by Paul Cézanne, Honoré Daumier, Edgar Degas, Raoul Dufy, Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renior, and James McNeil Whistler expected to realize in excess of $23 million.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), La route de Vétheuil, effet de neige, oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 32 1/8 in. Painted in 1879.

Estimate: $10,000,000-15,000,000

Leading the collection is Claude Monet’s, La route de Vétheuil, effet de neige, painted in 1879 (estimate: $10,000,000-15,000,000). Monet painted this exquisitely subtle and delicate view of Vétheuil under heavy snow in 1879, during his first full year living in the rural hamlet about sixty kilometers northwest of Paris. This canvas is the first in a sequence of three painted from approximately the same vantage point, exploring the changes in the winter landscape over a period of days. The three years spent at Vétheuil represent a decisive moment of artistic reassessment for the Impressionist painter. It was here that Monet abandoned scenes of modern life and leisure that had dominated his earlier work and began to focus on capturing the fleeting aspects of nature, employing a nascent serial technique that laid the groundwork for his most important later production.