One of the most extraordinary artistic and intellectual movements of the 20th century wase explored in Surrealism: Desire Unbound, on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art February 6 through May 12, 2002. More than 300 works including paintings, sculpture, photographs, films, poems, manuscripts, and books will explore the first major artistic movement to address openly the topics of love, desire, and various aspects of sexuality.

The exhibition had been organized by Tate Modern, London. (Great exhibition website here)

Surrealism embraced not only art and literature, but also psychoanalysis, philosophy, and politics. The Surrealists aimed to liberate the human imagination through an aesthetic investigation of desire—the authentic voice, they believed, of the inner self and the impulse behind love. Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), one of the movement's earliest precursors as well as one of its first proponents, initially reflected on how to express desire in art around 1912, and throughout his career he continued to make eroticism the central theme of his work. Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978), whose interest in dreams and groupings of seemingly disparate objects (which would later become Surrealist hallmarks) is also regarded as a precursor of the movement. The focus on dreams and desire reflected, in part, a familiarity with the writing of Sigmund Freud, the influential founder of psychoanalysis and a theorist who identified the sexual instincts and their sublimation as factors central to the development of the individual and of civilization as a whole. The intensity of the Surrealists' commitment to a broad, uncensored vision of human nature helped sustain and define the movement from its birth in the 1920s to its demise in the late 1950s.

Such Surrealist luminaries as Man Ray (1890-1976), Max Ernst (1891-1976), Joan Miró (1893-1983), André Masson (1896-1987), René Magritte (1898-1967), Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), and Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) will be represented, as well as artists not so widely known. The exhibition included works by several women artists—such as Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), Dorothea Tanning (b. 1910), Leonora Carrington (b. 1917), and others—some of whom have been largely overlooked in previous surveys. Also featured were examples of Surrealist writings about love and desire in an illuminating selection of rare and original books, manuscripts, letters, and other documentary materials.

Among the highlights of Surrealism: Desire Unbound was The Invisible Object (Hands Holding the Void) (1934, cast ca. 1954-5, The Museum of Modern Art, New York). This beckoning sculpture by Alberto Giacometti captivated André Breton (1896-1966), the leader of the Paris-based Surrealism group, who saw it in Giacometti's studio and wrote about it extensively in his revolutionary texts. In Breton's evocation of the work, The Invisible Object encapsulates the dynamics of the Surrealist encounter—the desire to love and be loved, the potential prelude to amorous and erotic experience, the impulse to make contact and at the same time maintain distance.

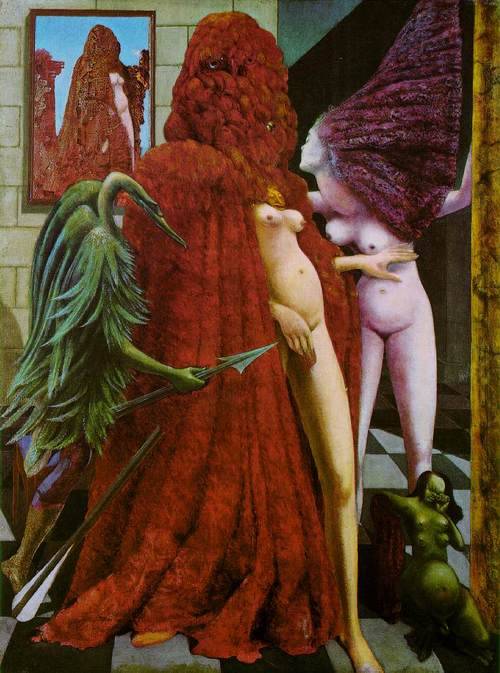

The Robing of the Bride (1940, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice), by Max Ernst,

is a theatrical and rich narrative painting evocative of witch trials of the Middle Ages.

The universal, mystical symbolism in

Men Shall Know Nothing of This (1923, Tate, London),

Ernst's image of a copulating couple floating in mid-air, suggests inexplicable ritual and alchemistic design that both generates and suppresses eroticism.

The Rape (1934, The Menil Collection, Houston),

René Magritte's meticulously painted image of a woman's face depicted as a female body, also suggests ambiguous sexuality; it was seen as a key Surrealist work by Breton.

Always her own favorite subject, Frida Kahlo used her image in scenarios that were vibrantly symbolic and naïve, unfettered by either the realism of Mexican muralists or the formal concerns of modernism.

Her 1940 Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair(The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

is an angry and forlorn expression of retaliation against Diego Rivera, to whom she was married, divorced, and remarried. In this depiction, painted during a time of their separation, she has cut off the long hair he loved, and stripped herself of feminine adornments except for her earrings and shoes. The shorn hair multiplies and spreads across the landscape as if alive.

Following a love affair with Leonora Carrington and his subsequent marriage to Peggy Guggenheim (a collector of Surrealist works), Max Ernst met Dorothea Tanning in 1942. Surrealism: Desire Unbound included

a self-portrait

that Tanning had painted on the occasion of her 30th birthday, in which she portrayed herself standing at the nexus of a labyrinth of open and closed doors, bare-breasted yet semi-clothed. A winged creature resembling a griffin crouches at her bare feet. The painting suggests discovery and flight. Tanning and Ernst later married and lived together in Sedona, Arizona, and Paris, France.

The mingling of love and a demanding, sometimes aggressive sexuality is perhaps nowhere better or more disturbingly shown than in the work of Hans Bellmer (1902-1975), whose Surrealist photographs explore sensual pleasure and psychic anxiety through pictures of large, specially-constructed dolls. Darker aspects of desire are also evoked in works by Surrealist masters Joan Miró and Roland Penrose (1900-1984), among many others who remain remarkable not so much for their openness in sexual matters as for their refusal to allow love to be divorced from eroticism. In their portrayals of encounter, desire, and carnality, the Surrealists continue to facilitate ways of seeing the world anew.

At the Metropolitan, Surrealism: Desire Unbound was organized by William S. Lieberman, Jacques and Natasha Gelman Chairman of Modern Art, with the assistance of Anne L. Strauss, Assistant Curator.

The exhibition was previously on view in fall, 2001, at Tate Modern, London, where it was curated by Jennifer Mundy, Senior Curator, Collections Division, Tate, with consultants Dawn Ades and Vincent Gille.

The accompanying catalogue, Surrealism: Desire Unbound (2001, Tate Publishing Ltd) was edited by Mundy, and it includes her essay as well as essays by other scholars.