The Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale on 27 June, part of 20th Century at Christie’s, a series of sales that take place from 17 to 30 June 2017, will be led by a group of masterpiece paintings by Max Beckmann, Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso, Egon Schiele and Vincent van Gogh.

Claude Monet’s Saule pleureur (1918-19, estimate: £15,000,000-25,000,000) is arguably one of the best of a series of ten works depicting the weeping willows surrounding Monet’s famous lily pond at Giverny, five of which reside in museum collections. Stripped of water and sky and painted with a heavily impastoed surface, the abstraction of Monet’s late works was a powerful influence on a generation of American abstract expressionist artists.

Painted between 1918 and 1919, Saule pleureur is one of a series of ten monumental and powerfully emotive paintings, each of which depict one of the majestic weeping willow trees that lined Monet’s famed waterlily pond at his home in Giverny. Following the death of the artist’s eldest son, in 1914, Monet had been working with a fearsome resolve on what came to be known as his Grandes décorations. Born from an earlier idea to create an immersive decorative scheme based on his waterlily paintings, this ambitious, all-consuming and ground-breaking project consisted of paintings on a scale never before seen in the artist’s career. The formidable verticality of the weeping willow series has come to represent the artist’s resolve and patriotic fervour at the conclusion of the First World War.

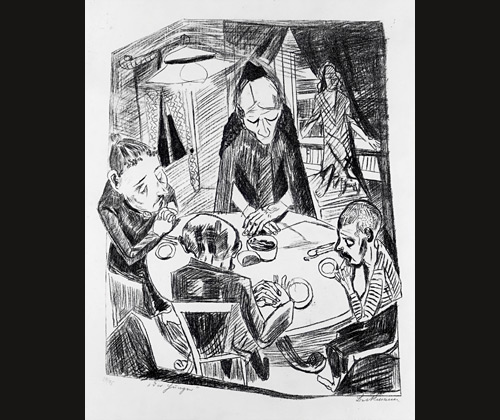

A visionary approach is also seen in the allegory of Max Beckmann’s political masterpiece Birds’ Hell (Hölle derVögel) (1937-1938, estimate on request), a searing indictment of the Nazi Party and a personal outpouring of anguish akin to

Picasso’s Guernica (1937).

Birds’ Hell (Hölle derVögel) is ‘an allegory of Nazi Germany. It is a direct attack on the cruelty and conformity that the National Socialist seizure of power brought to Beckmann’s homeland. Its place in Beckmann’s oeuvre corresponds to that occupied by Guernica in Picasso’s artistic development. It is an outcry as loud and as strident as an artistic Weltanschauung would permit. Not since his graphic attacks in

Hunger

and City Night

in the early twenties had Beckmann resorted to such directness, such undisguised social criticism. Birds’ Hell is Beckmann’s J’accuse’ (S. Lackner, Max Beckmann, New York, 1977, p. 130).

Max Beckmann’s Bird’s Hell (1938, estimate on request) will lead 20th Century at Christie’s, a series of sales that take place from 17 to 30 June 2017, in the Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale on 27 June 2017, when it will be offered at auction for the first time. One of the most powerful paintings that Beckmann created while in exile in Amsterdam it presents a searing and unforgettable vision of hell and is poised to set a world record price for the artist at auction. Begun in Amsterdam and completed in Paris at the end of 1938, this work ranks amongst the clearest and most important anti-Nazi statements that the artist ever made, mirroring the escalating violence, oppression and terror of the National Socialist regime.

Painted with vigorous, almost gestural brushstrokes and bold, garish colours, Bird’s Hell envelops the viewer in a sinister underworld in which monstrous bird-like creatures are engaged in an evil ritual of torture. Presiding over the scene is a multi-breasted bird who emerges from a pink egg in the centre of the composition. To her right, a crouching black and yellow bird looms over golden coins spread before him, while behind the central figure, a group of naked women stand huddled together. Heightening the sense of hysteria is the group of figures standing within a glowing, blood red doorway to the left of the composition. Guarded by another knife-wielding bird, they return the bird-woman’s gesture, their right arms raised in unison in the same furious salute. At the front of the scene, a naked man – the symbol of innocence within this reign of terror – is shackled to a table, held down by another bird that is slashing his back in careful, horizontal lines.

Continuing the Germanic tradition of the depiction of hell, this painting echoes the gruesome allegorical scenes of Hieronymus Bosch’s famed The Garden of Earthly Delights, while at the same time, takes aspects of Classicism and mythology to turn reality into a timeless evocation of human suffering. In this way, Bird’s Hell, like Pablo Picasso’s Guernica or

Max Ernst’s Fireside Angel of the same period, transcends the time and the political situation in which it was made to become a universal and singular symbol of humanity.

Max Ernst’s Fireside Angel of the same period, transcends the time and the political situation in which it was made to become a universal and singular symbol of humanity.

Egon Schiele’s Einzelne Häuser (Häuser mit Bergen) (1915, estimate: £20,000,000-30,000,000) is a cityscape used to convey human emotion, expressing the duality of life and decay, nature and humanity.

Schiele created landscapes filled with melancholy, charging the natural world with a deeper spiritual meaning. The autumnal setting of Einzelne Häuser (Häuser mit Bergen) can be seen as a metaphor for mortality; the crumbling facades of the townscape and surrounding trees used as an alternate physical expression of the elemental forces of growth, death and decay.

Einzelne Häuser (Häuser mit Bergen) is one of the finest of Egon Schiele’s great series of psychological landscapes painted in 1915. Depicting an isolated group of distinctly weather-worn houses huddled together against a bleak, open landscape, the painting is one of a magnificent series of landscape visions that articulate a mood of existential melancholy and rank amongst the very best of Schiele’s works.

As with almost all of Schiele’s townscapes, the buildings in Einzelne Häuser (Häuser mit Bergen) appear to represent his mother’s hometown, Krumau, a medieval Bohemian town on the Moldau River, known today as Český Krumlov on the Vltava in the Czech Republic. Schiele painted Einzelne Häuser (Häuser mit Bergen) on the reverse of a fragment of an older picture known as Monk I that dates from 1913. It is believed to have formed part of one of his largest attempted projects, Bekehrung (‘Conversion’), and is linked to the two monumental allegories that he produced the same year, of which only fragments, sketches and photographic evidence are now known.

Vincent van Gogh’s Le moissonneur (1889, estimate £12,500,000-16,500,000) is one of a series of ten works executed after Jean-François Millet’s Les travaux des champs– seven of which are in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam – described by his brother Theo as “perhaps the finest things you’ve done.”

Painted at Saint-Rémy in September 1889 at a critical moment in the penultimate year of Vincent van Gogh’s life, Le moissonneur (d’après Millet) pays homage to the artist whom he most admired and respected: Jean-François Millet. Charged with intense colour and electrifying brushwork, this painting dates from the beginning of one of the most prolific periods of Van Gogh’s career, a stage that saw an almost miraculous outpouring of work in the midst of the artist’s episodic yet ever-increasing mental breakdowns that punctuated the final years of his life.

Le Moissonneur (d’après Millet) is one of ten paintings that Van Gogh made after a series of drawings by Jean-François Millet entitled Les Travaux des Champs (1852), seven of which now reside in the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, with the other two in private hands. The work of Millet became a major focus for Van Gogh during this period, following the gift of a set of engravings of Millet’s Les Travaux des Champs by Jacques-Adrien Lavielle that was sent to Van Gogh from his brother Theo van Gogh the same year. Le Moissonneur (d’après Millet), employs the composition of Millet but is filled with Van Gogh’s own dramatic and intense use of colour. With his back to the viewer, bent over as he works the fields, the male figure is illuminated against the deep blue sky and golden yellow fields.

Pablo Picasso’s Femme écrivant (Marie-Thérèse) (1934, estimate: £25,000,000-40,000,000) completes the group of masterpieces from the June sale and is a radiant and intimate portrait that epitomises one of the finest periods of the artist’s career. It represents the pinnacle of the artist’s portrayals of one of his most celebrated muses.

Painted on 26 March 1934, Femme écrivant (Marie-Thérèse) dates from the pinnacle of Marie-Thérèse’s supreme reign in Picasso’s art. 1934 was a particularly prolific year for Picasso and was the final period that the pair spent wrapped in the uninterrupted bliss of their love. While Marie-Thérèse most often appears as a sensuously reclining, somnolent nude or a stylised vision enthroned in a chair, a passive object of adoration, in the present work Picasso has depicted her in an upright, active state, engaged in the act of writing a letter – a common form of exchange that Marie-Thérèse and the artist used to express their affection amidst the secrecy of their relationship.

See complete discussion of this work here.

Further highlights include Modigliani’s Cariatide (1913, estimate: £6,000,000-9,000,000), which stands as an intriguing crossover work, straddling the boundary between Modigliani’s two principal creative impulses of painting and sculpture.

Executed in 1913, Cariatide is a rare example of Amedeo Modigliani’s painterly practice during this early period of his artistic career, in which he focused primarily on sculpture. One of only a handful of oil paintings which explore the form of a sculpted caryatid, the present work illustrates the complex working process that lay behind each of the artist’s three-dimensional projects in stone. Creating countless drawings and sketches before ever taking his hammer to a block, these studies offered Modigliani a forum in which to experiment and visualise the ideas that swirled around his head, before translating them into sculptural form.

Following the success of February’s sale of works from the Heidi Weber Museum Collection by Le Corbusier, Mains croisées sur la tête (1939-40, estimate: £1,200,000-2,000,000) is a painting that has a strong dialogue with the symbolic portraiture of Picasso.

Painted in 1939 and completed a year later, Le Corbusier’s Mains croisées sur la tête marked a new direction in the artist’s plastic oeuvre. Standing at a metre high, this large painting presents a glorious kaleidoscopic array of bright, radiant colours in the middle of which a heavily stylised mask-like face emerges. This is the first of a series of works in which Le Corbusier explored both the physiognomy of the human face as well as the complex psychological nuances that lay behind his conception of the human form.

Hannah Höch’s Frau und Saturn (1922, estimate: £400,000-600,000) is an intimate autobiographical work, created during a period of intense turmoil and upheaval in the artist’s personal life and is one of the most significant works by Höch to come up at auction.

Painted in 1922, Frau und Saturn focuses on a trio of otherworldly, mystical figures, and may be seen as a personal reflection on the tumultuous romance Hannah Höch shared with fellow Dada artist, Raoul Hausmann, which had ended the same year as the painting’s creation. Höch took the difficult decision to terminate two pregnancies during their time together and it is this internal conflict, this unfulfilled wish to have a child, which shapes Frau und Saturn. At the heart of the composition sits the glowing, red figure of a woman cradling a young child, an imaginary self-portrait of the artist, caught in a moment of intimacy as she touches her cheek against the baby’s head, while behind her the menacing figure of Hausmann emerges glowering from the dark shadows of the background.