Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

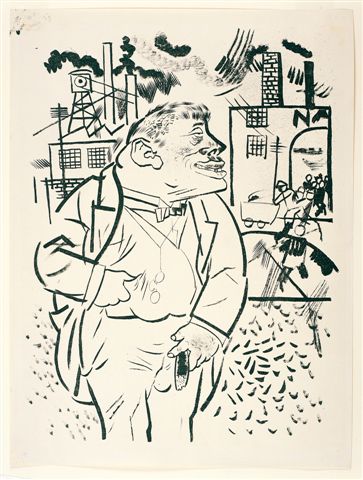

George Grosz (Germany, 1839–1959), "Lions and tigers nourish their young, ravens feast their brood on carrion... Series: The Robbers" (detail), 1922, Photolithograph on paper, 27 1/2 x 19 3/4 inches. Gift of David and Eva Bradford, 2002.53.6.5, Art © Estate of George Grosz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

In February 2018, the Portland Museum of Art will open The Robbers: German Art in a Time of Crisis in the Palladian Gallery. The exhibition of approximately thirty German prints executed between the World Wars will highlight the complete portfolio of George Grosz’s 1922 The Robbers. Grosz based his lithographic suite on Friedrich Schiller iconic 1781 play of the same name, yet when Grosz depicted the canonical story he situated the action in the tumultuous climate of early 1920s Berlin.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

With figures culled from the modern era, Grosz’s imagery suggests the vast social discord where the traumatic effects of the mechanized war, greed, industry, and poverty intersected to undermine national stability in the young Weimar Republic.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Grosz’s prints were part of a broader artistic culture in which other printmakers and theater directors produced modern interpretations of canonical of German literature, overtly politicizing the hallmarks of the nation’s cultural heritage. Their work, available to broad audiences through widely disseminated prints or stage performances, was a type of social intervention at a moment when conceptions of German identity vacillated wildly. The interplay between contemporaneous politics and historic literature highlighted the tensions between tradition and modernity, which strained German society and which remain continually resonant today across the world.

In addition to the Grosz’s Robbers portfolios, the exhibition will also include provocative artworks, by printmakers including Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz. These works, many of which are gifts to the PMA from David and Eva Bradford, add context to Grosz’s social and artistic expression and are equally probing in their evaluation of German society and national identity.

More images

Many of these prints, including the Grosz series, represent a post-World War I aesthetic known as “New Objectivity.” Whereas German expressionists of an earlier generation often depicted emotional responses to the modern condition, highlighting themes of angst, inner turmoil, and social alienation, the leaders of New Objectivity rooted their prints in a type of biting, provocative realism, often relying on satire and caricature.

The division between the two styles was never absolute, and both allowed artists to participate actively in cultural debates about social class, politics, and modern, urban phenomena. Because of their goals to be socially engaged artists shaping the national discourse, many of the artists working in these styles found the print medium to be especially efficient as prints could be disseminated more broadly than painting or sculpture.

This exhibition, opening in the centenary year of the end of World War I, turns our attention away from the conflict itself and towards the aftermath that defined the next two decades. History, politics, art, and national identity will intersect and provoke questions about who we are and what we value in ways that are as pertinent today as they were a century ago.

Image:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

With figures culled from the modern era, Grosz’s imagery suggests the vast social discord where the traumatic effects of the mechanized war, greed, industry, and poverty intersected to undermine national stability in the young Weimar Republic.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Georg Grosz, "I will root up from my path whatever obstructs my progress towards becoming the master" Act 1 Scene 2; From The Robbers by Friedrich Schiller, ...

Grosz’s prints were part of a broader artistic culture in which other printmakers and theater directors produced modern interpretations of canonical of German literature, overtly politicizing the hallmarks of the nation’s cultural heritage. Their work, available to broad audiences through widely disseminated prints or stage performances, was a type of social intervention at a moment when conceptions of German identity vacillated wildly. The interplay between contemporaneous politics and historic literature highlighted the tensions between tradition and modernity, which strained German society and which remain continually resonant today across the world.

In addition to the Grosz’s Robbers portfolios, the exhibition will also include provocative artworks, by printmakers including Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz. These works, many of which are gifts to the PMA from David and Eva Bradford, add context to Grosz’s social and artistic expression and are equally probing in their evaluation of German society and national identity.

More images

Many of these prints, including the Grosz series, represent a post-World War I aesthetic known as “New Objectivity.” Whereas German expressionists of an earlier generation often depicted emotional responses to the modern condition, highlighting themes of angst, inner turmoil, and social alienation, the leaders of New Objectivity rooted their prints in a type of biting, provocative realism, often relying on satire and caricature.

The division between the two styles was never absolute, and both allowed artists to participate actively in cultural debates about social class, politics, and modern, urban phenomena. Because of their goals to be socially engaged artists shaping the national discourse, many of the artists working in these styles found the print medium to be especially efficient as prints could be disseminated more broadly than painting or sculpture.

This exhibition, opening in the centenary year of the end of World War I, turns our attention away from the conflict itself and towards the aftermath that defined the next two decades. History, politics, art, and national identity will intersect and provoke questions about who we are and what we value in ways that are as pertinent today as they were a century ago.

Image: