The career of William H. Johnson (1901–1970) was one of the most brilliant yet tragic of any early 20th-century American artist. Best known for his lively paintings of the African American experience in the rural South and urban North, Johnson was also an accomplished printmaker and watercolorist whose style shifted from dramatic expressionism to what he termed a more “primitive” approach using bright and contrasting colors and flattened, two-dimensional forms. William H. Johnson’s World on Paper examined, for the first time, his achievements as a graphic artist. Delicate watercolor drawings, bold block prints, and colorful screenprints reveal him as an inventive modernist.

The exhibition, on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from May 19 through August 12, 2007, was drawn largely from the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the largest and most extensive holding of Johnson’s work in all mediums.

Born in 1901 in Florence, S.C., to a poor family, Johnson moved to New York at age 17, just in time for the first flowering of the Harlem Renaissance. Working a variety of jobs, he saved enough money to pay for an art education at the prestigious National Academy of Design. Johnson worked with painter Charles Hawthorne, who raised funds to send Johnson abroad to study. He spent the late 1920s in France, absorbing the lessons of modernism. During this period, he married Danish artist Holcha Krake. The couple spent most of the 1930s in Scandinavia, where Johnson’s interest in folk art had a profound impact on his work. Returning with Holcha to the United States in 1938, Johnson immersed himself in African American culture and traditions. Although Johnson attained some success as an artist in this country and abroad, financial security remained elusive. Following his wife’s death in 1944, Johnson’s physical and mental health deteriorated; he spent the final 23 years of his life in obscurity, confined to a state hospital in Long Island, N.Y.

Seventy-nine works were featured in the show, including block prints, screenprints, oil and tempera paintings, along with selected drawings and watercolors, providing an overview of Johnson’s career, both in Europe in the 1930s and in New York in the 1940s. Among the varied subjects of his work are early landscapes of Denmark, Norway and North Africa; portraits of his neighbors in Denmark; scenes of daily life in Harlem and the rural South; and scenes of black enlisted men and female volunteers of World War II. The exhibition reveals Johnson’s stylistic development from his academic beginnings to a more expressionistic mode and finally to his distinctive form of figurative abstraction based on folk art and African colors and patterns.

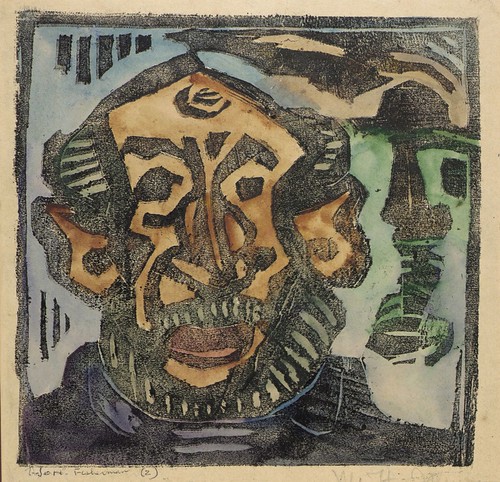

While in Europe, Johnson came in contact with the art of Edvard Munch, whose rough-gouged experimental block prints seem to have inspired Johnson to try new printmaking techniques. The unevenly inked black areas in some of the artist’s block prints, such as Jon Fisherman (2), suggest that Johnson did not use a printing press but instead applied pressure to the back of the paper with the bowl of a spoon or the heel of his hand to transfer the wet ink from the block to the paper.

Back in the United States in the late 1930s Johnson continued to make block prints while at the same time he was attracted to the screenprint technique. A stencil method developed in the 1920s for printing signboards and posters, in the 1930s the screenprint was adopted by artists to make limited edition prints. It was as a screenprint artist that Johnson would leave his most lasting mark as a printmaker. The bright-hued, opaque inks and the hand cut stencils used for making screenprints proved to be ideal for translating the sharp edges and flat expanses of his new painting style, which appears to have been inspired in equal parts by the colorful cartoons of his childhood, the folk art of Scandinavia and North Africa, and the African American folk traditions of his own country.

William H. Johnson’s World on Paper was organized and circulated by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Itinerary

An exhibition of more than 40 prints was on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (July 1, 2006 through Jan. 7, 2007). An expanded version of the exhibition that included selected drawings and watercolors toured to the Amon Carter Museum in Forth Worth, Texas (Feb. 3 – April 8, 2007), the Philadelphia Museum of Art (May 19 – August 12, 2007) and the Montgomery Museum of Art, in Montgomery, Ala. (Sept. 15 –Nov. 18, 2007). In Philadelphia the exhibition was further enriched by the inclusion of several of Johnson’s oil paintings and prints from private collections.

William H. Johnson, Sowing, about 1940-1942, serigraph on paper, 10 x 16

From theartblog.org: (link added)

Harlem Cityscape with Church, c. 1939-40, William H. Johnson (1901-1970). Tempera on paperboard. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation.

Jitterbugs (V), c. 1941-1942, William H. Johnson (1901-1970). Color silkscreen print. Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of Mrs. Douglas E. Younger.

Jon Fisherman II, c. 1930-1938, William H. Johnson (1901-1970). Hand-colored block print. Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of the Harmon Foundation.

While Johnson’s earlier work is influenced by German Expressionism and Impressionism, after his return from Europe to New York in 1938, his work becomes something else entirely. He moves to the graphic flatness of silkscreen as well as watercolor, pen and ink and pencil, moving easily back and forth among those mediums; the resulting work has a feel of collage, quilting and applique. The African-American quilting influence also seems to be reflected in the willful anti-rectilinearity.

What’s stunning is the few short years, from 1939 to 1945, in which he was able to produce work in this mature style–colorful, geometric, using the rhythm of repeating shapes. It’s deceptively childlike. And wow, is it beautiful! The work from that period is mostly narrative. It’s lively even when the subject matter is dark, as when he depicts a young soldier leaving his family farm for World War II, or when he depicts injured soldiers.

William H. Johnson, Going to Church, c. 1941, silkscreen

Johnson was creating a narrative of quotidian African-American lives at the mid-century. Like Pippin and Jacob Lawrence, he created a John Brown image–it’s included in the exhibit. And there’s a sense of his boyhood Southern farm roots and his own move north, which paralells the African-American migration north of the previous generation. Lawrence’s Great Migration series was created in the same period as Johnson’s lively works on paper. But Johnson’s work is without the heroic political overlay. There’s the war and how it affected people. There’s the jitterbug dance craze. There’s a strong sense of family and the urban scene. It’s all put in personal terms.

The 1944 death of Johnson’s wife Holcha Krake (a Danish fiber-artist he met in France in 1929), had a severe effect on him, and by 1947, syphilis had destroyed his sanity altogether.

I left the exhibit of more than 80 works, wanting still more. Fortunately, I took home a catalog, Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson, by Richard J. Powell with an introduction by Martin Puryear. The book, which has a bunch of pictures of him as well as many images not in the exhibit, made me fall in love with the guy. He was handsome, sexy and intense, and if he were alive today he would probably be one of those celebrity artists who are as much public personae as they are artists (which is not to denigrate his art, which I personally love all the more for its folk art influences).

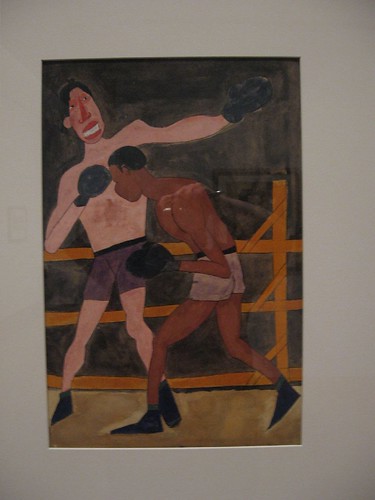

Joe Lewis and an Unidentified Boxer, c 1939-42, tempera, pen and ink on paper

More images from the exhibition:

William H. Johnson (1901-1970), Blind Singer, ca. 1939-1940, Serigraph on paper. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation 1971.127)

William H. Johnson (1901-1970), Jitterbugs II, ca. 1941, Modified screen print, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas 2000.11)

William H. Johnson (1901-1970), Three Friends, ca. 1944-1945, Serigraph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation 1967.59.1020)

William H. Johnson Lom Kirke, Norway hand-colored woodcut on paper, ca. 1935-1938

William H. Johnson Sitting Model hand-colored relief print, ca. 1939

William H. Johnson Willie and Holcha hand-colored woodcut on paper, ca. 1935

William H. Johnson Harlem Street with Church hand-colored relief print, ca. 1939-1940

William H. Johnson Farm Couple at Well hand-colored relief print, ca. 1940-1941