24 May – 23 September 2018

Tate Liverpool | Liverpool, UK

Tate Liverpool | Liverpool, UK

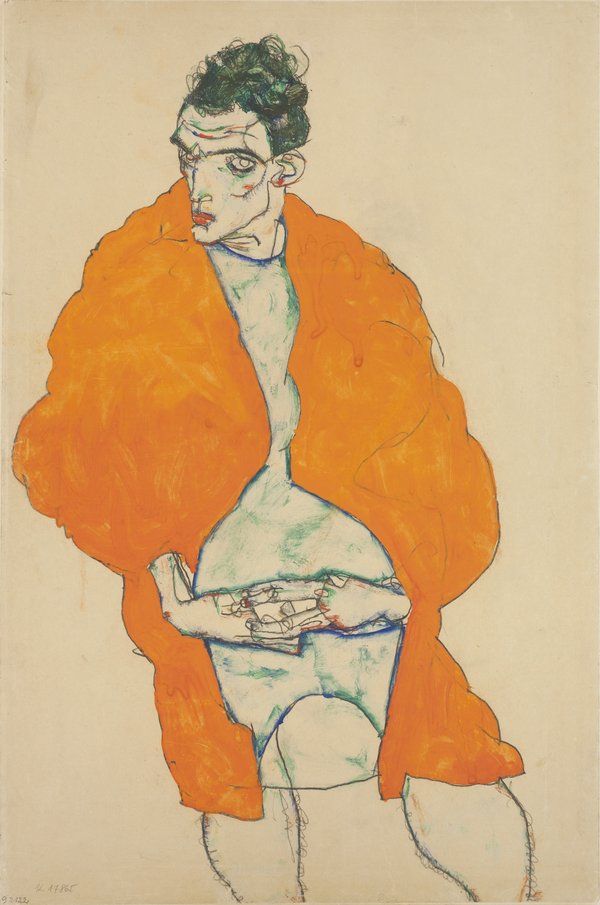

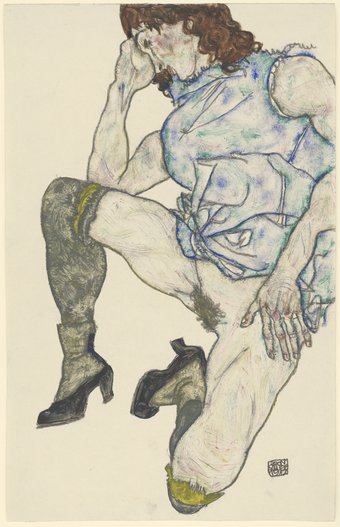

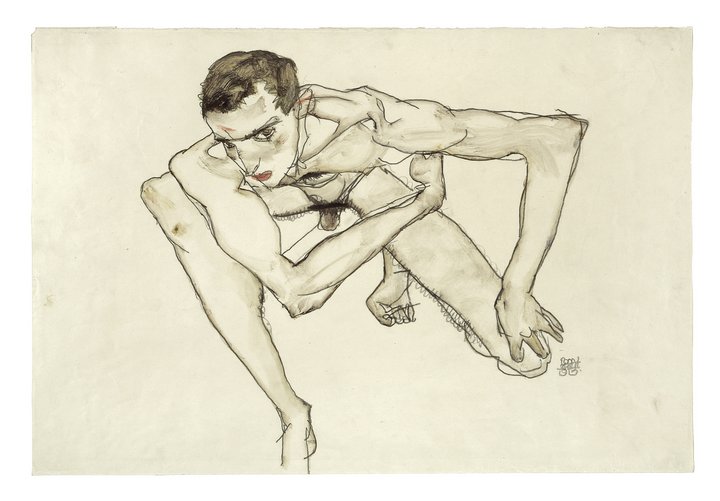

Life in Motion combines the work of radical Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele (1890 – 1918) and American photographer Francesca Woodman (1958 – 1981), exploring the remarkable ability of these artists to capture and suggest movement in order to create dynamic, extraordinary compositions that highlight the expressive nature of the human body. |

The exhibition offers a rare opportunity to see a large number of Schiele's drawings in the North of England, bringing attention to the artist's technical virtuosity, distinctive vision and unflinching depictions of the human figure. |

Working at the other end of the 20th century, Woodman's photographs help to refocus perceptions of Schiele's work, highlighting how his practices and ideas continue to have a relevance to contemporary art. The exhibition will include images from Woodman's My House Series, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 and her Eel Series, Roma, May 1977 - August 1978. |

Five things to know: Egon Schiele

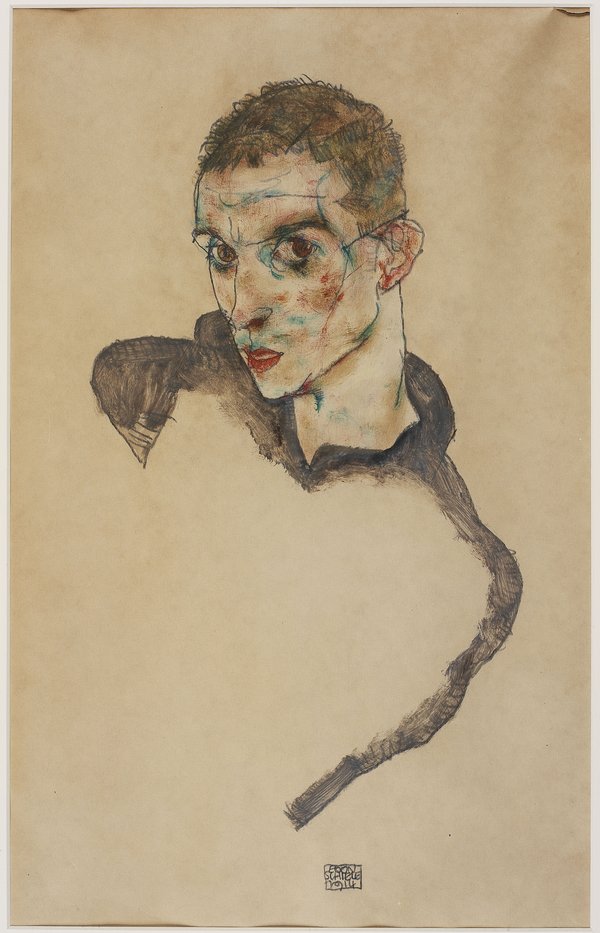

Egon Schiele, Standing male figure (self-portrait) 1914. Photograph © National Gallery in Prague 2017

1. HE WAS GUSTAV KLIMT’S PROTÉGÉ

As a teenager, Egon Schiele idolised Gustav Klimt. Klimt was the founder and leader of the Viennese Secession and had a wealth of experience in painting, sketching and murals. In 1907, Klimt became Schiele’s mentor and the two developed a close friendship. Both artists shared artistic traits and techniques, for example they drew elongated bodies, used expressive lines and injected bright colour into sketches. Klimt’s influence is noticeable in Schiele’s works produced between 1907 and 1909. Schiele painted The Hermits (Self-Portrait with Gustav Klimt) in 1912 as homage to their friendship. When Klimt died in February 1918, a devastated Schiele painted Klimt on his deathbed.2. HE COULDN’T TAKE HIS EYES OFF HIS SUBJECTS (LITERALLY)

3. HE HAD A RUN-IN WITH THE LAW

Schiele’s intense portraits frequently featured nude figures, which were unapologetic, contorted and emotionally-charged. In 1912, Schiele was arrested for distributing obscene drawings and the police confiscated hundreds of his works due to their sexually explicit nature. He was sentenced to 3 days in prison but, because he had already spent 21 days in custody, he didn’t serve the prison term. The judge, however, burnt one of his drawings during the trial as an act of warning.On 18 May he wrote to Arthur Roessler, who had not been in Vienna at the time of his arrest:

I am still completely shaken. During the trial a drawing of mine, the one I had hanging on the wall here, was burned. Klimt is hoping to do something. He assured me that the same thing could happen to one of us one day, another the next, that we're none of us free to do as we will.

4. HIS ART WAS GIVEN AN UNWANTED LABEL

5. HE DREW RIGHT UP UNTIL HIS DEATH

I love death and I love life

Egon Schiele