Dulwich Picture Gallery

![]()

In autumn 2018, Dulwich Picture Gallery will present Ribera: Art of Violence, the first UK show dedicated to the Spanish Baroque painter, draughtsman and printmaker Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), bringing together his most sensational and shocking works.

A selection of eight monumental canvases will be displayed alongside exceptional drawings and prints exploring the powerful theme of violence in Ribera’s art. Showcasing 45 works, the exhibition will be arranged thematically, examining his arresting depictions of saintly martyrdom and mythological violence, skin and the five senses, crime and punishment, and the bound male figure. Many of the works will be loaned from major European and North American institutions, on view in the UK for the first time.

Ribera (also known as lo Spagnoletto or ‘the little Spaniard’) has long been celebrated for his depictions of human suffering, a popular subject for artists during the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Born in Játiva, Valencia, Ribera spent most of his career in Naples, southern Italy, where he influenced many Neapolitan masters including Salvator Rosa and Luca Giordano. He is often regarded as the heir to Caravaggio for his dramatic use of light and shadow, and his practice of painting directly from the live model.

This exhibition will assess Ribera’s paintings, prints and drawings of violent subjects, which are often shocking and grotesque in their realism. It will demonstrate how his images of bodies in pain are neither the product of his supposed sadism nor the expression of a purely aesthetic interest, but rather involve a complex artistic, religious and cultural engagement in the depiction of bodily suffering.

The show will open with a room of religious violence, investigating Ribera’s depictions of the martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, who was flayed alive for his Christian faith. One of Ribera’s favoured subjects, Bartholomew was a common figure in southern European Baroque art, which aimed to reach out to the spectator and inspire devotion in post-Reformation Italy and Spain.

![Image result]()

![]()

Jusepe de Ribera, Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, 1644, Oil on canvas, 202 x 153 cm, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona. ©Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2018. Photo: Calveras/Mérida/Sagristà.

Highlights will include three versions of Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew spanning Ribera’s career, which reveal the evolution of the artist’s style and his hyper-realistic treatment of a shocking theme.

Throughout the exhibition, a selection of prints and drawings will illuminate Ribera’s mastery of composition, gesture and expression, with works ranging from anatomical figure studies to inquisition scenes of the strappado (punishment by hanging from the wrists). A room dedicated to skin and the five senses will celebrate Ribera as a graphic artist, with studies of eyes, ears, noses and mouths displayed alongside images of Bartholomew flayed alive.

A central theme is how Ribera broke new ground by capturing human suffering in his depictions of the male figure. The twisted pose of the male body in such drawings as Man Tied to a Tree (mid 1620s) from the Musée du Louvre, Paris, comprise a principal focus of Ribera’s works on paper, which vary from abbreviated preparatory studies for paintings and prints, to more elaborate sketches and independent sheets.

The exhibition will conclude with a room dedicated to one monumental painting, Apollo and Marsyas (1637), on loan from Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples, and the grand finale to the show. Paralleling Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, this painting – the tour de force of Ribera’s career – portrays Apollo flaying Marsyas alive as punishment for losing a musical competition. The painting encapsulates the argument of the exhibition, for it demonstrates the violent outcome of artistic rivalry and the visceral convergence of the senses, as the ripping of skin is experienced through the intersections of sight, touch and sound.

Ribera: Art of Violence is curated by Dr Xavier Bray, Director, The Wallace Collection, former Chief Curator, Dulwich Picture Gallery and curator of the 2009 exhibition The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600–1700 (National Gallery, London), and Dr Edward Payne, Head Curator: Spanish Art, The Auckland Project, County Durham, contributor to the catalogue raisonné of Ribera’s drawings (2016) and author of a PhD thesis on the theme of violence in Ribera’s art (2012).

Loans have been secured from a number of national and international institutions including the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona; Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao; Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence; Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Musée du Louvre, Paris; Rhode Island School of Design.

![Image result]()

![Image result]()

![Image result]()

" .

![Image result]()

![Image result]()

![Ribera - Martyrdom of St Bartholomew (Catalunya).jpg]()

![Image result]()

![https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Jusepe_de_Ribera_-_Crucifixion_of_Saint_Peter%2C_c.1625-1630_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/705px-Jusepe_de_Ribera_-_Crucifixion_of_Saint_Peter%2C_c.1625-1630_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg]()

A youthful figure is seen frontally with both arms extended, as if tied by invisible cords, his head thrown back. While the figure is neither bound by ropes nor shot with arrows, his exposed armpits support his identification as Saint Sebastian. By focusing on the moment before his first attempted execution (the saint was fully martyred by being beaten to death), Ribera explores the saint’s physical vulnerability as he pleas to heaven for help.

![Image result]()

In autumn 2018, Dulwich Picture Gallery will present Ribera: Art of Violence, the first UK show dedicated to the Spanish Baroque painter, draughtsman and printmaker Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), bringing together his most sensational and shocking works.

A selection of eight monumental canvases will be displayed alongside exceptional drawings and prints exploring the powerful theme of violence in Ribera’s art. Showcasing 45 works, the exhibition will be arranged thematically, examining his arresting depictions of saintly martyrdom and mythological violence, skin and the five senses, crime and punishment, and the bound male figure. Many of the works will be loaned from major European and North American institutions, on view in the UK for the first time.

Ribera (also known as lo Spagnoletto or ‘the little Spaniard’) has long been celebrated for his depictions of human suffering, a popular subject for artists during the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Born in Játiva, Valencia, Ribera spent most of his career in Naples, southern Italy, where he influenced many Neapolitan masters including Salvator Rosa and Luca Giordano. He is often regarded as the heir to Caravaggio for his dramatic use of light and shadow, and his practice of painting directly from the live model.

This exhibition will assess Ribera’s paintings, prints and drawings of violent subjects, which are often shocking and grotesque in their realism. It will demonstrate how his images of bodies in pain are neither the product of his supposed sadism nor the expression of a purely aesthetic interest, but rather involve a complex artistic, religious and cultural engagement in the depiction of bodily suffering.

The show will open with a room of religious violence, investigating Ribera’s depictions of the martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, who was flayed alive for his Christian faith. One of Ribera’s favoured subjects, Bartholomew was a common figure in southern European Baroque art, which aimed to reach out to the spectator and inspire devotion in post-Reformation Italy and Spain.

Jusepe de Ribera, Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew , 1624, Etching with engraving, Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations .

- Jusepe de Ribera

- Spanish, 1591 - 1652

- The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 1634

- oil on canvas

- overall: 104 x 113 cm (40 15/16 x 44 1/2 in.)

- framed: 134.6 x 143.8 x 10.2 cm (53 x 56 5/8 x 4 in.)

- Gift of the 50th Anniversary Gift Committee

- 1990.137.1

- On View:West Building, Main Floor - Gallery 29

.jpg)

Jusepe de Ribera, Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, 1644, Oil on canvas, 202 x 153 cm, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona. ©Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2018. Photo: Calveras/Mérida/Sagristà.

Highlights will include three versions of Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew spanning Ribera’s career, which reveal the evolution of the artist’s style and his hyper-realistic treatment of a shocking theme.

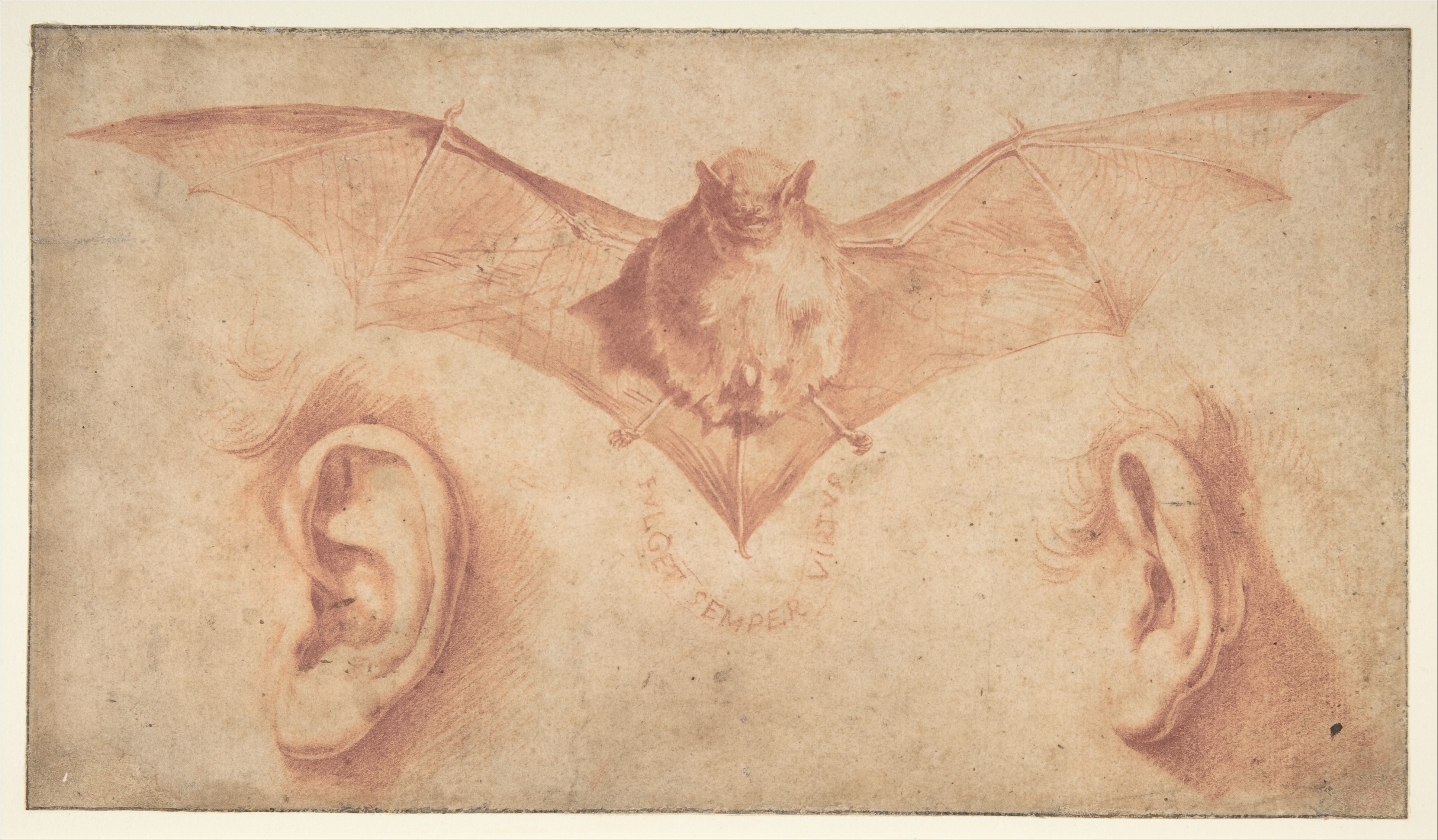

Throughout the exhibition, a selection of prints and drawings will illuminate Ribera’s mastery of composition, gesture and expression, with works ranging from anatomical figure studies to inquisition scenes of the strappado (punishment by hanging from the wrists). A room dedicated to skin and the five senses will celebrate Ribera as a graphic artist, with studies of eyes, ears, noses and mouths displayed alongside images of Bartholomew flayed alive.

A central theme is how Ribera broke new ground by capturing human suffering in his depictions of the male figure. The twisted pose of the male body in such drawings as Man Tied to a Tree (mid 1620s) from the Musée du Louvre, Paris, comprise a principal focus of Ribera’s works on paper, which vary from abbreviated preparatory studies for paintings and prints, to more elaborate sketches and independent sheets.

The exhibition will conclude with a room dedicated to one monumental painting, Apollo and Marsyas (1637), on loan from Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples, and the grand finale to the show. Paralleling Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, this painting – the tour de force of Ribera’s career – portrays Apollo flaying Marsyas alive as punishment for losing a musical competition. The painting encapsulates the argument of the exhibition, for it demonstrates the violent outcome of artistic rivalry and the visceral convergence of the senses, as the ripping of skin is experienced through the intersections of sight, touch and sound.

Ribera: Art of Violence is curated by Dr Xavier Bray, Director, The Wallace Collection, former Chief Curator, Dulwich Picture Gallery and curator of the 2009 exhibition The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600–1700 (National Gallery, London), and Dr Edward Payne, Head Curator: Spanish Art, The Auckland Project, County Durham, contributor to the catalogue raisonné of Ribera’s drawings (2016) and author of a PhD thesis on the theme of violence in Ribera’s art (2012).

Loans have been secured from a number of national and international institutions including the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona; Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao; Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence; Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Musée du Louvre, Paris; Rhode Island School of Design.

Jusepe de Ribera , Saint Sebastian , 1620 - 22 , Pen and brown ink , 24.8 x 1 4.8 cm , Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford , Oxford . © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford .

Jusepe de Ribera , A Bat and Two Ears , early 1620s , Red chalk, brush and red wash , 15.9 x 27.9 cm , The Metropolitan Museum of Art , Rogers Fund, 1972 . Photo: © 2018. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/ Scala, Florence

Jusepe de Ribera, Studies of the Nose and Mouth , c .1622, Etching, 14 x 21.6 cm, The British Museum , London . ©The Trustees of the British Museum . All rights reserved .

" .

Jusepe de Ribera, The Sense of Touch , 1632 , Oil on canvas, 125 x 98 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid . © Museo Nacional del Prado .

Jusepe de Ribera , Inquisition Scene , after 1635 , Pen and brown ink with wash , 20.6 x 16.5 cm , Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design , Providence, Museum Works of Art Fund 56.060 . Photo : Erik Gould, courtesy of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence .

Classical antiquity.

Idealised male bodies were considered the pinnacle of artistic production in art academies, notably the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, of which Ribera became a member in 1613. Pursuing the challenge of representing the human form, Ribera found inspiration in both the Classical ideal and in the real appearance of his live models to create hermits, martyrs and mythological figures.

Crucifixion of Saint Peter , mid-1620s

Jusepe de Ribera, “Study for Martyrdom of St. Sebastian” (c. 1626), red chalk on paper, William Lowe Bryan Memorial, Indiana University Art Museum

Jusepe de Ribera, Crucifixion of Saint Peter , mid - 1620s, Brush and red ink wash over red chalk, Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernan do , Madrid . Photo: © Museo de la Real Academia de Bella Artes de San Fernando, Madrid.

The apostle Peter was crucified upside down, having considered himself unworthy of suffering as Christ had done. Subtly executed in red wash and red chalk, this sheet depicts the preparations before Peter’s crucifixion. Running a rope through a split in the wood, the executioners have created an inventive pulley system to raise the saint’s body on the cross. Realising the composition as a whole, the artist combines highly finished figures with barely suggested ones. It is the most complete of Ribera’s three drawings of this subject.

Masterfully executed in ink and wash, this drawing is a variation on the theme of Saint Peter’s crucifixion. Ribera’s skillful handling of wash creates a dramatic contrast of light and shadow, and his deft pen strokes describe form and texture. The focus of this sheet is on the physical effort required to hoist the saint on the cross, which is raised at a steeper angle than in the other drawings of this subject, displayed nearby.

![Image result]()

Study for the Crucifixion of Saint Peter , mid-1620s

Pen and brown ink The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1919

This summary sketch of the crucifixion of Saint Peter was rapidly conceived. The saint’ s left arm is incomplete, while the profile of his legs has been corrected. Ribera likely drew from a live model posed on the ground to depict Peter at an angle, and without his executioners. Ribera scribbled his monogram and initial on the sheet. The various letter ‘Js’ stand for ‘Jusepe’, while the elaborate letter ‘E’ may refer to the artist’s Spanish nationality (español). In the lower right corner he also doodled a scorpion (escorpión in Spanish), a creature traditionally associated with treachery due to the sting in its tail. This may allude to Peter, who denied his knowledge of Jesus three times before Christ’s crucifixion.

Masterfully executed in ink and wash, this drawing is a variation on the theme of Saint Peter’s crucifixion. Ribera’s skillful handling of wash creates a dramatic contrast of light and shadow, and his deft pen strokes describe form and texture. The focus of this sheet is on the physical effort required to hoist the saint on the cross, which is raised at a steeper angle than in the other drawings of this subject, displayed nearby.

Study for the Crucifixion of Saint Peter , mid-1620s

Pen and brown ink The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1919

This summary sketch of the crucifixion of Saint Peter was rapidly conceived. The saint’ s left arm is incomplete, while the profile of his legs has been corrected. Ribera likely drew from a live model posed on the ground to depict Peter at an angle, and without his executioners. Ribera scribbled his monogram and initial on the sheet. The various letter ‘Js’ stand for ‘Jusepe’, while the elaborate letter ‘E’ may refer to the artist’s Spanish nationality (español). In the lower right corner he also doodled a scorpion (escorpión in Spanish), a creature traditionally associated with treachery due to the sting in its tail. This may allude to Peter, who denied his knowledge of Jesus three times before Christ’s crucifixion.

SAINT SEBASTIAN, MARTYR AND MODEL

Saint Sebastian was a subject that fascinated Ribera throughout his career. A young Roman soldier sentenced to death in the 4th century for his conversion to Christianity, Sebastian was initially shot with arrows and left for dead. He made a miraculous recovery, only to be martyred at a later date when he was beaten to death. Sebastian’s recovery caused him to be invoked as a protector during outbreaks of plague, whose symptoms include multiple swellings beneath the skin, notably under the armpits. Ribera made more than a dozen drawings, numerous paintings and one print of the subject. These images typically represent the saint with his armpit exposed, revealing his vulnerability. Collectively, they document and narrate pivotal moments in the legend of the saint: from preparing Sebastian for martyrdom, to shooting him with arrows, to tending his wounds.

![Image result]()

Saint Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women , c. 1620–23

Violence is both evoked and suppressed in this painting. The holy women tend to the reclining Sebastian, removing the arrows which pierce his body. Two angels bearing a crown and palm leaf, symbols of martyrdom, hover above the group. The painting contrasts with Ribera’s representations of Saint Bartholomew flayed alive: the subject here is healing rather than martyrdom, the flawless skin of the young Sebastian rather than the wrinkled flesh of the elderly Bartholomew. Ribera explores the tensions between the saint’s elegant pose and the pain implicit in the scene.

Saint Sebastian was a subject that fascinated Ribera throughout his career. A young Roman soldier sentenced to death in the 4th century for his conversion to Christianity, Sebastian was initially shot with arrows and left for dead. He made a miraculous recovery, only to be martyred at a later date when he was beaten to death. Sebastian’s recovery caused him to be invoked as a protector during outbreaks of plague, whose symptoms include multiple swellings beneath the skin, notably under the armpits. Ribera made more than a dozen drawings, numerous paintings and one print of the subject. These images typically represent the saint with his armpit exposed, revealing his vulnerability. Collectively, they document and narrate pivotal moments in the legend of the saint: from preparing Sebastian for martyrdom, to shooting him with arrows, to tending his wounds.

Jusepe de Ribera , Saint Sebastian Tended by theHoly Women, c. 1620 - 23 , Oil on canvas , 180 x 231 cm , Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao . © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa - Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao .

Saint Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women , c. 1620–23

Violence is both evoked and suppressed in this painting. The holy women tend to the reclining Sebastian, removing the arrows which pierce his body. Two angels bearing a crown and palm leaf, symbols of martyrdom, hover above the group. The painting contrasts with Ribera’s representations of Saint Bartholomew flayed alive: the subject here is healing rather than martyrdom, the flawless skin of the young Sebastian rather than the wrinkled flesh of the elderly Bartholomew. Ribera explores the tensions between the saint’s elegant pose and the pain implicit in the scene.

A youthful figure is seen frontally with both arms extended, as if tied by invisible cords, his head thrown back. While the figure is neither bound by ropes nor shot with arrows, his exposed armpits support his identification as Saint Sebastian. By focusing on the moment before his first attempted execution (the saint was fully martyred by being beaten to death), Ribera explores the saint’s physical vulnerability as he pleas to heaven for help.

Jusepe de Ribera, Man Bound to a Stake , first half of the 1640s, P en and brown ink with wash, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco , San Francisco Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts. Photo: © Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

Pen and brown ink Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Oxford Saint Sebastian being Tied to a Tree , late 1620s

A kneeling man binds Sebastian’s legs in preparation for his martyrdom. Tilting his head towards the spectator, the saint raises his right arm in the air and points down with his left. Given the sketchy nature of the sheet, which is characteristic of Ribera’s preparatory drawings, this work may be a preliminary study for a lost painting by the artist. Red chalk Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr

Saint Sebastian Tied to a Tree , c. 1627–30 Subtly rendered and starkly illuminated, Sebastian gazes up to the divine light that bathes his body. Rather than focusing on narrative, Ribera has created an iconic image of the bound figure. The use of red chalk accented with brown ink is unique among Ribera’s representations of the saint, demonstrating the artist’s abilities in combining media to suggest different textures. Notably, the top of the blasted tree trunk, executed solely in ink, evokes rough bark, while the skin of the saint, rendered in red chalk, appears smooth and soft. Red chalk with pen and brown ink The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland Delia E. Holden Fund, 1997.53

Saint Sebastian , second half of the 1630s Once attributed to Ribera’s contemporary Salvator Rosa (hence the inscription), this drawing of Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom is the most explicit of the group displayed here. The saint’s arms are bound above his head while one of the arrows piercing his body has gone straight through the flesh to lodge itself into the tree. Sebastian’s body cuts diagonally across the page, mirroring the tree trunk to which he is tied. Although it appears simple, the drawing’s sophisticated execution reveals the complexity of Ribera’s explorations of the bound figure. Pen, brown ink and brown wash Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

![Image result]()

Old Man Tied to a Tree and a Young Man Defecating , late 1620s The identity of the bound figure in this drawing is unclear, as Ribera was primarily concerned with exploring the contorted and restrained male body. Ribera creates a visual parallel between the figure and the tree: his torso resembles the trunk and his limbs echo the branch. The position of the central figure is difficult, if not anatomically impossible to recreate in reality, and the artist has exaggerated the proportions of the body, elongating the saint’s extended arm and leg. One of the most intriguing aspects of the sheet is the ambiguous r elationship between Wall Labels the bound man and the defecating figure at the foot of the tree. Proverbial language may provide a context for interpreting this drawing: one Spanish proverb runs, ‘Dung is no saint, but where it falls it works miracles’. Red chalk The Courtauld Gallery, London, The Samuel Courtauld Trust

![Image result]()

Man Bound to a Tree , mid-1620s Arms crossed and raised above his head, this figure twists in an elegant snake-like curve and seems to float on the page. His identity is ambiguous: the str etched, youthful body evokes Saint Sebastian, while the satirical, grimacing expression suggests something sinister. Typically, Ribera creates a visual parallel between the body of the figure and the form of the tree, whose gnarled trunk extends into sinewy limbs. One of Ribera’s most refined drawings, this sheet demonstrates the artist’s virtuoso handling of red chalk and innovative treatment of the bound man theme. Red chalk Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques, Paris

![Image result]()

Etching The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1953

A kneeling man binds Sebastian’s legs in preparation for his martyrdom. Tilting his head towards the spectator, the saint raises his right arm in the air and points down with his left. Given the sketchy nature of the sheet, which is characteristic of Ribera’s preparatory drawings, this work may be a preliminary study for a lost painting by the artist. Red chalk Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr

Saint Sebastian Tied to a Tree , c. 1627–30 Subtly rendered and starkly illuminated, Sebastian gazes up to the divine light that bathes his body. Rather than focusing on narrative, Ribera has created an iconic image of the bound figure. The use of red chalk accented with brown ink is unique among Ribera’s representations of the saint, demonstrating the artist’s abilities in combining media to suggest different textures. Notably, the top of the blasted tree trunk, executed solely in ink, evokes rough bark, while the skin of the saint, rendered in red chalk, appears smooth and soft. Red chalk with pen and brown ink The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland Delia E. Holden Fund, 1997.53

Saint Sebastian , second half of the 1630s Once attributed to Ribera’s contemporary Salvator Rosa (hence the inscription), this drawing of Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom is the most explicit of the group displayed here. The saint’s arms are bound above his head while one of the arrows piercing his body has gone straight through the flesh to lodge itself into the tree. Sebastian’s body cuts diagonally across the page, mirroring the tree trunk to which he is tied. Although it appears simple, the drawing’s sophisticated execution reveals the complexity of Ribera’s explorations of the bound figure. Pen, brown ink and brown wash Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Old Man Tied to a Tree and a Young Man Defecating , late 1620s The identity of the bound figure in this drawing is unclear, as Ribera was primarily concerned with exploring the contorted and restrained male body. Ribera creates a visual parallel between the figure and the tree: his torso resembles the trunk and his limbs echo the branch. The position of the central figure is difficult, if not anatomically impossible to recreate in reality, and the artist has exaggerated the proportions of the body, elongating the saint’s extended arm and leg. One of the most intriguing aspects of the sheet is the ambiguous r elationship between Wall Labels the bound man and the defecating figure at the foot of the tree. Proverbial language may provide a context for interpreting this drawing: one Spanish proverb runs, ‘Dung is no saint, but where it falls it works miracles’. Red chalk The Courtauld Gallery, London, The Samuel Courtauld Trust

Man Bound to a Tree , mid-1620s Arms crossed and raised above his head, this figure twists in an elegant snake-like curve and seems to float on the page. His identity is ambiguous: the str etched, youthful body evokes Saint Sebastian, while the satirical, grimacing expression suggests something sinister. Typically, Ribera creates a visual parallel between the body of the figure and the form of the tree, whose gnarled trunk extends into sinewy limbs. One of Ribera’s most refined drawings, this sheet demonstrates the artist’s virtuoso handling of red chalk and innovative treatment of the bound man theme. Red chalk Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques, Paris

Etching The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1953

A Winged Putto Flogging a Satyr Tied to a Tree , early 1620s A satyr – half man, half goat – is here portrayed with his arms bound to a tree trunk. He turns to face a winged child, who plunges towards him headfirst, menacingly raising a whip. The child is Cupid, Roman god of love, intent on chastising a lustful satyr who r epresents animal passion. The image of a bound satyr resonates closely with Ribera’s painting of the ill-fated Marsyas, on view in the final room.

MYTHOLOGICAL VIOLENCE

![Image result]()

Jusepe de Ribera , Apollo and Marsyas , 1637 , Oil on canvas , 182 x 23 2 c m, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples . Photo : Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimo nte on kind concession from the "Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo

The painting displayed in this room depicts one of the most violent stories from Classical mythology: the myth of Apollo and Marsyas.The foolish satyr Marsyas challenged Apollo, god of music and the arts, to a musical contest. The satyr was a skilled musician, but the god inevitably triumphed. In one version of the myth, Apollo sang while plucking the strings of his lyre; in another version, he played his instrument upside down. Marsyas lost the competition, as he could not replicate the god’s performances with his aulos, a wind instrument similar to a flute. Apollo’s prize was to punish Marsyas by flaying him alive. Ribera’s depiction of the story draws inspiration from the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses. As the torture began, the satyr cried, ‘Why do you tear me from myself?’ and screamed, ‘Oh, I repent! Oh, a flute is not worth such price!’ But the god did not forgive the satyr, and the flaying continued until Marsyas was ‘all one wound’. As the satyr’s blood flowed everywhere, the creatures of the woods wept for their unfortunate friend.

Apollo and Marsyas ,

1637 The unfortunate satyr Marsyas stares out helplessly at the spectator as the god Apollo, unnervingly serene, flays the satyr’s hide with his hands. Visible in the foreground is a Baroque instrument similar to a violin, depicted instead of the lyre used in Classical antiquity. Marsyas’ flute, here a panpipe, hangs from a tree branch. Ribera has used the story of musical rivalry between the satyr and the god to create a painting with many layers of meaning. Beyond representing a scene of extreme violence, this work warns against the dangers of hubris, the foolish arrogance that led Marsyas to challenge Apollo to a musical contest. No mortal artist, no matter how skilled, should ever dare to compete with a god. Yet the work is also a commentary on artistic practice itself, on the status of the arts and the potential for painting and sculpture to imitate reality. Athletic and pale, Apollo recalls the sculptures of Classical antiquity, like the marble bust on display in the first room. In Ribera’s paintings of the martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, the head of Apollo is not triumphant but overturned. In contrast, here Apollo seems to dominate Marsyas, as if sculpture had won the contest. Yet, this scene is represented through the art of painting. Perhaps Ribera is suggesting that painting and sculpture are not merely rivals, like the god and satyr, but companions.

The painting displayed in this room depicts one of the most violent stories from Classical mythology: the myth of Apollo and Marsyas.The foolish satyr Marsyas challenged Apollo, god of music and the arts, to a musical contest. The satyr was a skilled musician, but the god inevitably triumphed. In one version of the myth, Apollo sang while plucking the strings of his lyre; in another version, he played his instrument upside down. Marsyas lost the competition, as he could not replicate the god’s performances with his aulos, a wind instrument similar to a flute. Apollo’s prize was to punish Marsyas by flaying him alive. Ribera’s depiction of the story draws inspiration from the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses. As the torture began, the satyr cried, ‘Why do you tear me from myself?’ and screamed, ‘Oh, I repent! Oh, a flute is not worth such price!’ But the god did not forgive the satyr, and the flaying continued until Marsyas was ‘all one wound’. As the satyr’s blood flowed everywhere, the creatures of the woods wept for their unfortunate friend.

Apollo and Marsyas ,

1637 The unfortunate satyr Marsyas stares out helplessly at the spectator as the god Apollo, unnervingly serene, flays the satyr’s hide with his hands. Visible in the foreground is a Baroque instrument similar to a violin, depicted instead of the lyre used in Classical antiquity. Marsyas’ flute, here a panpipe, hangs from a tree branch. Ribera has used the story of musical rivalry between the satyr and the god to create a painting with many layers of meaning. Beyond representing a scene of extreme violence, this work warns against the dangers of hubris, the foolish arrogance that led Marsyas to challenge Apollo to a musical contest. No mortal artist, no matter how skilled, should ever dare to compete with a god. Yet the work is also a commentary on artistic practice itself, on the status of the arts and the potential for painting and sculpture to imitate reality. Athletic and pale, Apollo recalls the sculptures of Classical antiquity, like the marble bust on display in the first room. In Ribera’s paintings of the martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, the head of Apollo is not triumphant but overturned. In contrast, here Apollo seems to dominate Marsyas, as if sculpture had won the contest. Yet, this scene is represented through the art of painting. Perhaps Ribera is suggesting that painting and sculpture are not merely rivals, like the god and satyr, but companions.