At the Art Gallery of Hamilton (Ontario, Canada) November 1, 2014 to February 8, 2015

The exhibition was conceived by Benedict Leca, AGH Director of Curatorial Affairs, and organized by the Art Gallery of Hamilton in a special collaboration with the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, where the show opened to acclaim earlier this summer and broke attendance records.

Uniting 18 Cézanne paintings from around the world and another seven still lifes by his contemporaries, the exhibition features major works from acclaimed European and American museums and private collections, including the National Gallery (Washington), Musée d’Orsay, Stiftung Langmatt (Baden), Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Cincinnati Art Museum and the McMaster Museum of Art (McMaster University, Hamilton ON).

Soon after arriving in Paris in the 1860s, Cézanne created a notoriety for himself that was unprecedented in the history of French art. At the centre of this radical self-fashioning were still lifes of often glaring colours, skewed perspective, and thickly painted surfaces that unmoored objects and their meanings from conventional representation. Cézanne’s early work will first be put into context through the presentation of 4 exceptional realist still lifes from the AGH collection to show how he departed from convention.

Early Cézanne will be represented in the exhibition by three first-rate works including the masterful

Still Life with Bread and Eggs (1865) from Cincinnati.

Later, Cézanne established his distinctive style through works such as

Still Life with Fruit and Glass of Wine (c. 1877, Philadelphia Museum of Art),

Still Life: Flask, Glass, and Jug (c. 1877, . Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, )

and

![]()

Apples and Cakes (1877, Private Collection), recasting the physical and perceptual relations between people and things.

Extending their traditional meanings as symbols of abundance, vanity, or rusticity, Cézanne instead used apples, skulls or crockery to create a visual language of punning juxtapositions and poetic allusion. His paintings invite viewers to rethink the world and the place of man and objects in it.

“While he surely looked closely at nature, Cézanne self-consciously plays with colours, forms and space in a manner that invites a free association that contrasts with the fixed meanings of academic tradition,” said exhibition curator Benedict Leca. “He creates an alternative world where things can move improbably and mean variously. The traditional ‘silent life of things’ that he explodes is about containment and Cézanne is all about evasion,” affirmed Leca.

As the so-called “Painter of Apples,” Cézanne returned many times to his signature motif, working through the complexities of colour application and its effects. Cézanne’s famous apple paintings will be represented by three exceptional examples:

Seven Apples and a Tube of Color, Apples on a Chair (1878-80, Lausanne, Musée cantonal), and

Some Apples (1878-80, Stiftung Langmatt, Baden).

Also on view will be a contrasting pair of flower paintings:

The Dark Blue Vase III (1880)

from the Kreeger Museum is a small-scale, intimate work in which Cézanne explores pattern,

while the large, late

Vase of Flowers from the National Gallery in Washington exemplifies Cézanne’s late life obsessions with contours and surfaces.

Over the course of his career painting still lifes, Cézanne pushed the boundaries of meaning and form while simultaneously evolving a highly structured compositional style characterized by ever more deliberate arrangements of objects. His so-called ‘Classic’ phase of still life painting culminates in the 1890s and is represented in the exhibition by major works such as the

Musée d’Orsay’s The Kitchen Table (c. 1890) and

Fruit and Ginger Pot (1890-93) from the Stiftung Langmatt.

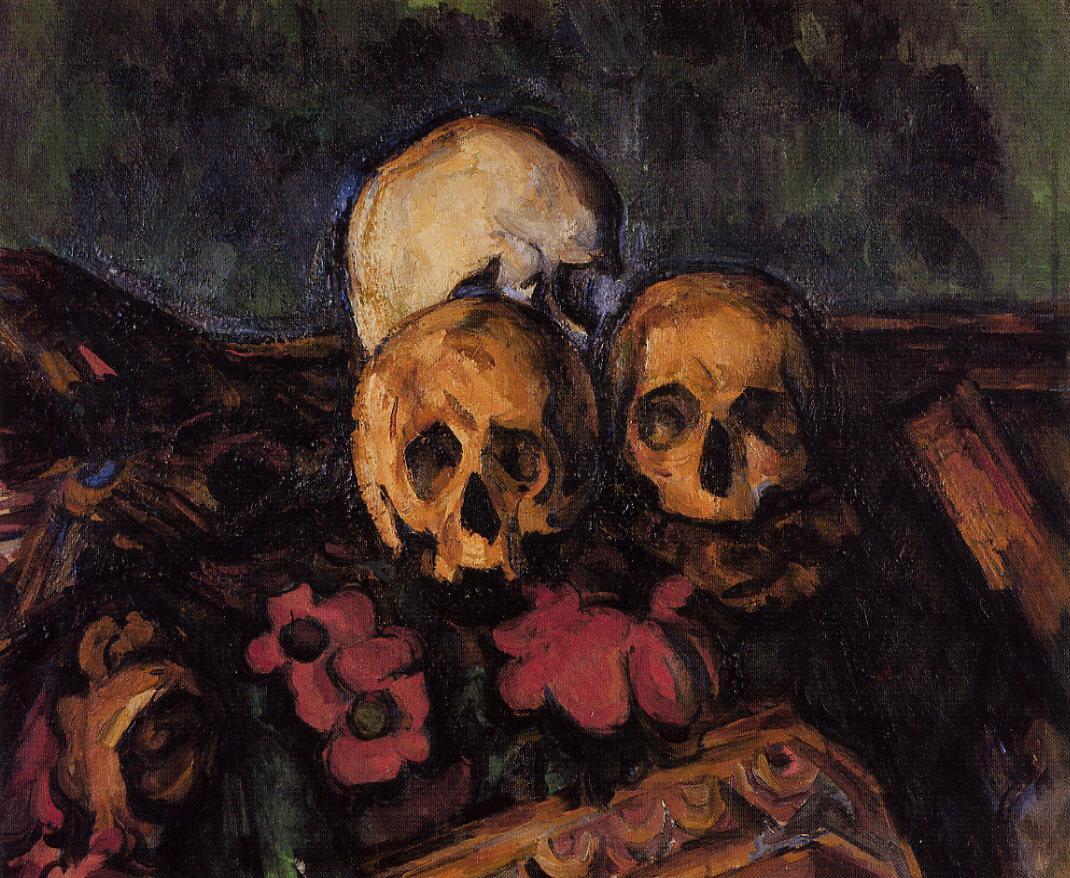

The latest works in the exhibition will be anchored by the two greatest paintings of skulls Cézanne ever created,

Three Skulls (Detroit Institute of Arts) and

Three Skulls on a Patterned Carpet (Kunstmuseum, Solothurn).

A prolific artist who synthesized formal problems through a close study of objects, Cézanne’s lifelong engagement with still life painting yielded what is arguably the single most innovative body of work in the genre of any artist in the Western canon. Ultimately, Cézanne set still life painting on a new course, one that completely altered its traditionally low position in the academic hierarchy of French painting and prefigured the later essays of masters from Pablo Picasso to Andy Warhol.

The exhibition closes with three important paintings by artists who keyed on Cézanne in their own engagement with still life: Vincent van Gogh, Maurice Denis, Georges Braque.

Soon after arriving in Paris in the 1860s, Cézanne created a notoriety for himself that was unprecedented in the history of French art. At the centre of this radical self-fashioning were still lifes of often glaring colours, skewed perspective, and thickly painted surfaces that unmoored objects and their meanings from conventional representation. Cézanne’s early work will first be put into context through the presentation of 4 exceptional realist still lifes from the AGH collection to show how he departed from convention.

Early Cézanne will be represented in the exhibition by three first-rate works including the masterful

Still Life with Bread and Eggs (1865) from Cincinnati.

Later, Cézanne established his distinctive style through works such as

Still Life with Fruit and Glass of Wine (c. 1877, Philadelphia Museum of Art),

Still Life: Flask, Glass, and Jug (c. 1877, . Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, )

and

Apples and Cakes (1877, Private Collection), recasting the physical and perceptual relations between people and things.

Extending their traditional meanings as symbols of abundance, vanity, or rusticity, Cézanne instead used apples, skulls or crockery to create a visual language of punning juxtapositions and poetic allusion. His paintings invite viewers to rethink the world and the place of man and objects in it.

“While he surely looked closely at nature, Cézanne self-consciously plays with colours, forms and space in a manner that invites a free association that contrasts with the fixed meanings of academic tradition,” said exhibition curator Benedict Leca. “He creates an alternative world where things can move improbably and mean variously. The traditional ‘silent life of things’ that he explodes is about containment and Cézanne is all about evasion,” affirmed Leca.

As the so-called “Painter of Apples,” Cézanne returned many times to his signature motif, working through the complexities of colour application and its effects. Cézanne’s famous apple paintings will be represented by three exceptional examples:

Seven Apples and a Tube of Color, Apples on a Chair (1878-80, Lausanne, Musée cantonal), and

Some Apples (1878-80, Stiftung Langmatt, Baden).

Also on view will be a contrasting pair of flower paintings:

The Dark Blue Vase III (1880)

from the Kreeger Museum is a small-scale, intimate work in which Cézanne explores pattern,

while the large, late

Vase of Flowers from the National Gallery in Washington exemplifies Cézanne’s late life obsessions with contours and surfaces.

Over the course of his career painting still lifes, Cézanne pushed the boundaries of meaning and form while simultaneously evolving a highly structured compositional style characterized by ever more deliberate arrangements of objects. His so-called ‘Classic’ phase of still life painting culminates in the 1890s and is represented in the exhibition by major works such as the

Musée d’Orsay’s The Kitchen Table (c. 1890) and

Fruit and Ginger Pot (1890-93) from the Stiftung Langmatt.

The latest works in the exhibition will be anchored by the two greatest paintings of skulls Cézanne ever created,

Three Skulls (Detroit Institute of Arts) and

Three Skulls on a Patterned Carpet (Kunstmuseum, Solothurn).

A prolific artist who synthesized formal problems through a close study of objects, Cézanne’s lifelong engagement with still life painting yielded what is arguably the single most innovative body of work in the genre of any artist in the Western canon. Ultimately, Cézanne set still life painting on a new course, one that completely altered its traditionally low position in the academic hierarchy of French painting and prefigured the later essays of masters from Pablo Picasso to Andy Warhol.

The exhibition closes with three important paintings by artists who keyed on Cézanne in their own engagement with still life: Vincent van Gogh, Maurice Denis, Georges Braque.

A fully illustrated, scholarly catalogue co-published by the Art Gallery of Hamilton and D Giles Limited (London) accompanies the exhibition, with essays by Benedict Leca, as well as art historians Paul G. Smith, Richard Shiff and Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmeyer, in addition to a foreword by Philippe Cézanne, great-grandson of the artist.

From a review of the same exhibition at the Barnes:

From a review of the same exhibition at the Barnes:

The Kitchen Table (La table de cuisine) by Paul Cezanne, 1888-1890.Musee d'Orsay/Courtesy of the Barnes FoundationPablo Picasso once said that the great 19th-century French painter Paul Cezanne was "the father of us all." Cezanne's distinctive brush strokes, and the way he distorted perspective and his subjects, influenced the cubists, and most artists who came after him. In Philadelphia, the Barnes Foundation is showing a group of still-life paintings by Cezanne.

The current special exhibition is all about naked fruit — apples, mostly. It's called "The World Is an Apple: The Still Lifes of Paul Cezanne."iJoe Rishel, of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, describes Cezanne's work as "repetitive apples with apples." But that's not to say it's boring. With Cezanne, Rishel says, "Every game is a new game." That's partly because of the idiosyncratic way Cezanne arranged his apples before he painted them.

"He would stick little wedges of any kind, sometimes fat little coins, underneath them just to prop them up," Rishel says. "Isn't that cute?"

Cezanne propped one apple higher than others, put another at an angle and pushed another into the foreground. Then he painted them. "I want to astonish Paris with an apple," he's said to have said. And, coming to town from his southern country village of Aix-en-Provence, he did astonish.

"They thought he was crazy," says Benedict Leca, the Barnes show curator and director of curatorial affairs at the Art Gallery of Hamilton in Ontario, Canada. "People said he was on drugs, even. People said that he was dabbling in hashish and that he was out of his mind."

They said all that because they'd never seen brushwork like this.

"These are very short, parallel strokes, very clearly painted," says Judith Dolkart, chief curator at the Barnes. "He does nothing to ... hide his hand."

The paint is thick, almost chiseled onto the canvas. You can see the edges of each hatched stroke. And, subtly, within each paint stroke, the colors change. One has more white in it; the one next to it is darker.

Sugar Bowl, Pears, and Blue Cup (Sucrier, poires et tasse bleue) by Paul Cezanne, circa 1866.Musee d'Orsay/Courtesy of the Barnes FoundationDolkart says, "Every time he is lifting his brush, he's declaring, 'I'm a painter. This is my medium. These are my materials.'"

According to Leca, for a French viewer in the late 19th century, "an apple painted with these distinct strokes in this kind of rough-hewn manner would have been shocking."

Another excellent review: (image added)

...In the earliest still life here, “Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup,” c. 1866, the painter seems to be working his way through his influences. The fruits and ceramic ware in this canvas are described with wet-into-wet paint reminiscent of Édouard Manet’s (1832-1883) alla prima process, troweled on with a palette knife technique that brings to mind Gustave Courbet (1819-1877).

Another exploratory still life, “The Dark Blue Vase III,” c. 1880, looks informed by the Japonisme popular at the time among Impressionists. In this small, vertical canvas, stylized stems and flowers float above a china vase. The bottom edge of this picture, carefully painted to look unfinished, may give exhibition visitors pause, inviting viewers to rethink the numerous “unfinished” Cézannes as considered, complete works

Beyond studio experiments, a few magnificent loans add heft to this show. The National Gallery of Art’s “Vase of Flowers,” 1900/1903, is bumpy from layer after layer of paint application, a testament to Cézanne’s tenacity. A busy canvas from the Musée d'Orsay, “The Kitchen Table,” 1888-1890, expertly juggles a lot of information, with fruits, cloth, ginger jar, pots and a basket teetering on a table, making for an unstill still life.

“Three Skulls on an Oriental Rug,” 1898-1905, also thick with paint from multiple revisions, is a powerful painting. Recalling his apprenticeship in the master’s Aix-en-Provence studio, artist Émile Bernard said: “The colors and shapes in this painting changed almost every day, and each day when I arrived at his studio it could have been taken from the easel and considered a finished work of art. In truth, his method of study was a meditation with a brush in his hand.”

Exhibition organizers suggest Cézanne turned to this macabre motif in response to his mother’s death in 1897. In “Three Skulls on an Oriental Rug,” the skulls wear haunted expressions as they sit in a cluster on a dark, patterned cloth. With no jawbones, the frightened skulls in this affecting picture seem to make muffled screams....