Frick Collection June 9 through September 6, 2015

Born in Scarborough, Yorkshire, in 1830, Frederic Leighton was one of the most renowned artists of the Victorian era. He was a painter and sculptor, as well as a formidable presence in the art establishment, serving as a longtime president of the Royal Academy, and he forg ed an unusual path between academic classicism and the avant-garde. The recipient of many honors during his lifetime, he is the only British artist to have been ennobled, becoming Lord Leighton, Baron of Stretton, in the year of his death. Nevertheless, he leftalmost no followers, and his impressive oeuvre was largely forgotten in the twentieth century. Leighton’s virtuoso technique, extensive preparatory process, and intellectual subject matter were at odds with the generation of painters raised on Impressionism, with its emphasis on directness of execution.

One of his last works, however, Flaming June, an idealized sleeping woman in a semi - transparent saffron gown, went on to enduring fame. From June 9 to September 6, Leighton’s masterpiece will hang at the Frick, on loan from the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico.

One of his last works, however, Flaming June, an idealized sleeping woman in a semi - transparent saffron gown, went on to enduring fame. From June 9 to September 6, Leighton’s masterpiece will hang at the Frick, on loan from the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico.

The exhibition , which is accompanied by a publication and series of public programs, is organized by Susan Grace Galassi, Senior Curator, The Frick Collection. Leighton’s Flaming June is made possible by The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation and Mr. and Mrs. Juan A. Sabater. Comments Galassi, “Despite the painting’s renown, it has never before been exhibited in New York.

Alongside the imposing canvas will be displayed a small oil sketch from a private collection that Leighton made in developing the painting’s palette. The works have not been together since the late nineteenth century, and we couldn’t be more pleased to offer our visitors this special viewing opportunity. These two related works by Leighton will hang in the Oval Room, surrounded by the Frick’s four full - length portraits by American expatriate James McNeill Whistler, Leighton’s contemporary . This arrangement marks the return to view of the Whistler portraits and offers a fresh chance to consider the relationship of the two artists’ modern masterpieces. ”

ABOUT FREDERIC LEIGHTON

Frederic Leighton was the son of a wealthy English physician. At the age of fifteen, he began his artistic training at the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt, where his family had recently moved, eventually studying under Edward von Steinle, an artist of the Nazarene school. Having perfected his master’s precise, linear manner of drawing, he traveled to Rome to continue his studies, joining an international community of artists.

While there, Leighton carried out a monumental oil painting richly filled with detail,

Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna is Carried in Procession through the Streets of Florence (1853 – 55, National Gallery, London, on loan from the Royal Collection).

His first work to be accepted for exhibition at the Royal Academy, it was bought by Queen Victoria for Buckingham Palace, making the twenty - four - year - old Leighton an instant celebrity.

Following more than a decade in Germany and Italy, Leighton spent three years in Paris, at a time when Ingres and Delacroix dominated the scene. He became increasingly drawn to color, confessing to Steinle his “fanatic preference” for it over line, although he excelled in both. In 1859 he returned to his native country, where his strong academic training, immersion in Renaissance and classical art, and firstha nd experience with the current trends in the major art capitals of Europe set him apart from many of his English contemporaries.

In London, Leighton met members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, as well as James McNeill Whistler; with them, he shaped the radical movement of Aestheticism, with its emphasis on the formal aspects of art. Yet despite Leighton’s insistence on the preeminence of composition, design, and the harmony of color over subject matter, his work frequently draws from literary sources and is imbued with poetic associations.

FLAMING JUNE : A CLOSER LOOK

Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1895, Flaming June belongs to a group of works painted during Leighton’s final decade that feature idealized female figures. These physically robust and sensual protagonists take on a variety of attitudes — some pose as sibyls or muses in moments of inspiration while others are asleep or absorbed in meditative states. Of these powerful late works, Flaming June most immediately impacts the viewer with its eroticism and color harmony, its appealing composition, and elusive subject matter. Wrapped in radiant, liquid drapery that reveals the form of her naked body beneath, a beautiful young woman seated in profile fills much of a perfectly square canvas. She is lost in a dream, but her body is dynamic, seeming to rotate in on itself in a continuous loop. Closer to a bas-relief than to a figure in the round, she is integrated into a spare classical setting resembling a marble terrace or parapet. On the right, a bouquet of oleanders rests on a ledge and a decorative awning borders the edge of the canvas. The finely blended brushstrokes used for the model’s flesh and areas of the chiffon dress are offset by thick impastoed strokes representing the shimmering sea in the distance.

While Leighton’s ingenious composition immediately draws the viewer in, the complex form of the body counters the apparent serenity of the sleeping woman. On closer inspection, a discrepancy between her upper and lower body emerges. Both legs are bent at s harp angles, and the left knee rises steeply above the right — almost to the level of the head. The right leg, greatly elongated, extends across her body in a powerful horizontal, diving downward at the knee in a sharp diagonal, the ball of her foot pressing into the floor. Her bare arms, bent at the elbows, mimic the angularity of her legs and create a frame for the lightly veiled breasts and head , which rests on the crook of her arm. While the two halves of the body mirror each other to a certain extent, th e upper body is characterized by physical passivity and the flight of the conscious mind, while the lower is robustly physical, conveying a sense of restless vitality and sexuality. Associations with earlier works of art hint at another layer of meaning. Leighton would have expected contemporary viewers to note his references to famous works by Michelangelo, whom he revered. The configuration of the legs of Flaming June and her curled position evoke one of the sixteenth - century master’s most erotic works,

Leda and the Swan of 1529, as well as his marble sculpture Night, created slightly earlier, on which Leda was based. While the model for Flaming June faces in the opposite direction, the allusions to these famous works bring with them connotations of death and blatant eroticism. Is Flaming June more femme fatale than sleeping beauty?

THEMES AND SYMBOLS IN VICTORIAN POETRY

In his essay in the exhibition’s accompanying publication, Pablo Pérez d’Ors, Associate Curator of European Art at the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico, explores the interpretation of the painting in the context of Leighton’s life and in relation to themes and symbols in Victorian poetry, with which the highly literate artist would have been familiar. A medical condition, angina pector is, from which Leighton was suffering at the time of painting Flaming June, would have made him aware that the end of his life was approaching; in fact, Leighton was too ill to attend the opening of the Royal Academy exhibition in May 1895, where Flaming June and several other canvases were accorded places of honor. The artist and longtime president of the Academy died eight months later.

In Victorian poetry, sleep and death are frequently equated, while oleanders often symbolize danger. Fleshy in appearance and intensely fragrant, these voluptuous flowers appeal directly to the senses, yet are highly poisonous, leading Pérez d’Ors to question whether their presence in the painting suggests that the sleeping woman, like the flowers, might be as dangerous as she is alluring. Such associations, deliberately ambiguous, have undoubtedly contributed to the hold the painting has exerted on the imaginations of generations of viewers.

FROM DRAWING TO OIL SKETCH TO FINISHED PAINTING

Although the meaning of Flaming June remains elusive, Leighton’s path to its creation was deliberate and well documented , as discussed in Susan Galassi’s catalogue essay . The number of extant drawings for Flaming June attests to the importance of the painting for him and provides a view into his creative process, which was shaped by the rigorous methods learned in the academies of Europe and practiced throughout his life. Beginning with a mental image of a pose, sparked by a chance observation or drawn from his imagination or a work of art of the past, Leighton made a series of studies of a nude model until he arrived at the position that coincided with his initial idea. He then made drawings of the model draped and a compositional study. With the format and composition established, his final step was to make an oil sketch to work out the painting’s palette.

Here he established the color scheme, using avibrant red - orange for the dress and dark neutral tones for the draperies strewn on the bench. At far left on the horizon of a sparkling sea, he added an island (which would disappear in the finished work), as well as a scalloped - edged awning that runs across the top of the picture.

On the canvas itself, measuring about forty - seven by forty - seven inches, Leighton made final adjustments. The scalloped edge of the awning is replaced by a straight edge, and the orange of the gown — painted in his characteristically meticulous manner — attains an even greater radiance. The painting was generally well received at its presentation at the Royal Academy; one reviewer writing for the London Times (May 4, 1895) referred to “that peculiar reddish orange of which Sir Frederic Leighton’s palette alone seems to possess the secret, and this is harmonized, in that manner of his which is so familiar, against other draperies of dark crimson and pale olive. Nothing need be said in praise of the drawing of this figure, in the difficulties of which the artist has evidently found one of his chief pleasures; for problems of drawing are child’s play to him.”

THE INSTALLATION AT THE F RICK : LEIGHTON , WHISTLER , AND AESTHETICISM

Leighton and Whistler — near exact contemporaries — were two of the most prominent figures in the London art world in the late nineteenth century . They cultivated widely disparate artistic identities at a time of increasingly emphatic division between the academic and the avant- arde in Europe. Following traditional methods, Leighton produced meticulously painted canvases with a high degree of finish. By contrast, Whistler embraced a distinctly modern manner, employing free brushwork, thin veils of paint, and deliberately flattened forms. While Leighton was an exceptionally private man whose presidency of the increasingly outmoded Royal Academy shaped his public persona, Whistler was vocal, openly combative, and well known for his eccentricities and anti - establishment sentiments.

Nevertheless , in spite of their disparate methods and reputations, the two men shared deeply rooted — and radical — artistic principles, as important proponents of Aestheticism. Underpinned by the concept of “art for art’s sake” — the belief in the independent value of art apart from any didactic, moral, or political purpose — Aestheticism called for the prioritization of formal qualities of color and line over subject matter. Both Leighton and Whistler created Aesthetic masterpieces in which color and line are indeed primary, yet also serve to evoke mood or character. A comparison of Leighton’s Flaming June — a painting of an anonymous figure freed from any narrative context or specificity of time and place — and

Whistler’s Harmony in Pink and Grey: Portrait of Lady Meux — a commissioned portrait of a member of high society — reveals these shared aims. Both works explore the dual impact of the beauty of the female body and the visual power of color. The two images — one a voluptuou s woman who stares suggestively at the viewer, the other a sleeping beauty in the presence of a poisonous flower — draw on the archetype of the femme fatale. In both, the body is submitted to abstraction, becoming a dynamic play of angles and curves, while remaining a palpable presence. In Flaming June, the model’s limbs are elongated and arranged to form a spiral within a perfectly square canvas, while the serpentine line of Lady Meux’s body is accentuated by her costume — a tight - fitting satin waistcoat and a train with a chiffon ruffle that cascades to the ground in rhythmic folds. The paintings make their sensory impact through this combination of pure form and the sensuality of the body.

Alongside the imposing canvas will be displayed a small oil sketch from a private collection that Leighton made in developing the painting’s palette. The works have not been together since the late nineteenth century, and we couldn’t be more pleased to offer our visitors this special viewing opportunity. These two related works by Leighton will hang in the Oval Room, surrounded by the Frick’s four full - length portraits by American expatriate James McNeill Whistler, Leighton’s contemporary . This arrangement marks the return to view of the Whistler portraits and offers a fresh chance to consider the relationship of the two artists’ modern masterpieces. ”

ABOUT FREDERIC LEIGHTON

Frederic Leighton was the son of a wealthy English physician. At the age of fifteen, he began his artistic training at the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt, where his family had recently moved, eventually studying under Edward von Steinle, an artist of the Nazarene school. Having perfected his master’s precise, linear manner of drawing, he traveled to Rome to continue his studies, joining an international community of artists.

While there, Leighton carried out a monumental oil painting richly filled with detail,

Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna is Carried in Procession through the Streets of Florence (1853 – 55, National Gallery, London, on loan from the Royal Collection).

His first work to be accepted for exhibition at the Royal Academy, it was bought by Queen Victoria for Buckingham Palace, making the twenty - four - year - old Leighton an instant celebrity.

Following more than a decade in Germany and Italy, Leighton spent three years in Paris, at a time when Ingres and Delacroix dominated the scene. He became increasingly drawn to color, confessing to Steinle his “fanatic preference” for it over line, although he excelled in both. In 1859 he returned to his native country, where his strong academic training, immersion in Renaissance and classical art, and firstha nd experience with the current trends in the major art capitals of Europe set him apart from many of his English contemporaries.

In London, Leighton met members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, as well as James McNeill Whistler; with them, he shaped the radical movement of Aestheticism, with its emphasis on the formal aspects of art. Yet despite Leighton’s insistence on the preeminence of composition, design, and the harmony of color over subject matter, his work frequently draws from literary sources and is imbued with poetic associations.

FLAMING JUNE : A CLOSER LOOK

Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1895, Flaming June belongs to a group of works painted during Leighton’s final decade that feature idealized female figures. These physically robust and sensual protagonists take on a variety of attitudes — some pose as sibyls or muses in moments of inspiration while others are asleep or absorbed in meditative states. Of these powerful late works, Flaming June most immediately impacts the viewer with its eroticism and color harmony, its appealing composition, and elusive subject matter. Wrapped in radiant, liquid drapery that reveals the form of her naked body beneath, a beautiful young woman seated in profile fills much of a perfectly square canvas. She is lost in a dream, but her body is dynamic, seeming to rotate in on itself in a continuous loop. Closer to a bas-relief than to a figure in the round, she is integrated into a spare classical setting resembling a marble terrace or parapet. On the right, a bouquet of oleanders rests on a ledge and a decorative awning borders the edge of the canvas. The finely blended brushstrokes used for the model’s flesh and areas of the chiffon dress are offset by thick impastoed strokes representing the shimmering sea in the distance.

While Leighton’s ingenious composition immediately draws the viewer in, the complex form of the body counters the apparent serenity of the sleeping woman. On closer inspection, a discrepancy between her upper and lower body emerges. Both legs are bent at s harp angles, and the left knee rises steeply above the right — almost to the level of the head. The right leg, greatly elongated, extends across her body in a powerful horizontal, diving downward at the knee in a sharp diagonal, the ball of her foot pressing into the floor. Her bare arms, bent at the elbows, mimic the angularity of her legs and create a frame for the lightly veiled breasts and head , which rests on the crook of her arm. While the two halves of the body mirror each other to a certain extent, th e upper body is characterized by physical passivity and the flight of the conscious mind, while the lower is robustly physical, conveying a sense of restless vitality and sexuality. Associations with earlier works of art hint at another layer of meaning. Leighton would have expected contemporary viewers to note his references to famous works by Michelangelo, whom he revered. The configuration of the legs of Flaming June and her curled position evoke one of the sixteenth - century master’s most erotic works,

Leda and the Swan of 1529, as well as his marble sculpture Night, created slightly earlier, on which Leda was based. While the model for Flaming June faces in the opposite direction, the allusions to these famous works bring with them connotations of death and blatant eroticism. Is Flaming June more femme fatale than sleeping beauty?

THEMES AND SYMBOLS IN VICTORIAN POETRY

In his essay in the exhibition’s accompanying publication, Pablo Pérez d’Ors, Associate Curator of European Art at the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico, explores the interpretation of the painting in the context of Leighton’s life and in relation to themes and symbols in Victorian poetry, with which the highly literate artist would have been familiar. A medical condition, angina pector is, from which Leighton was suffering at the time of painting Flaming June, would have made him aware that the end of his life was approaching; in fact, Leighton was too ill to attend the opening of the Royal Academy exhibition in May 1895, where Flaming June and several other canvases were accorded places of honor. The artist and longtime president of the Academy died eight months later.

In Victorian poetry, sleep and death are frequently equated, while oleanders often symbolize danger. Fleshy in appearance and intensely fragrant, these voluptuous flowers appeal directly to the senses, yet are highly poisonous, leading Pérez d’Ors to question whether their presence in the painting suggests that the sleeping woman, like the flowers, might be as dangerous as she is alluring. Such associations, deliberately ambiguous, have undoubtedly contributed to the hold the painting has exerted on the imaginations of generations of viewers.

FROM DRAWING TO OIL SKETCH TO FINISHED PAINTING

Although the meaning of Flaming June remains elusive, Leighton’s path to its creation was deliberate and well documented , as discussed in Susan Galassi’s catalogue essay . The number of extant drawings for Flaming June attests to the importance of the painting for him and provides a view into his creative process, which was shaped by the rigorous methods learned in the academies of Europe and practiced throughout his life. Beginning with a mental image of a pose, sparked by a chance observation or drawn from his imagination or a work of art of the past, Leighton made a series of studies of a nude model until he arrived at the position that coincided with his initial idea. He then made drawings of the model draped and a compositional study. With the format and composition established, his final step was to make an oil sketch to work out the painting’s palette.

Here he established the color scheme, using avibrant red - orange for the dress and dark neutral tones for the draperies strewn on the bench. At far left on the horizon of a sparkling sea, he added an island (which would disappear in the finished work), as well as a scalloped - edged awning that runs across the top of the picture.

On the canvas itself, measuring about forty - seven by forty - seven inches, Leighton made final adjustments. The scalloped edge of the awning is replaced by a straight edge, and the orange of the gown — painted in his characteristically meticulous manner — attains an even greater radiance. The painting was generally well received at its presentation at the Royal Academy; one reviewer writing for the London Times (May 4, 1895) referred to “that peculiar reddish orange of which Sir Frederic Leighton’s palette alone seems to possess the secret, and this is harmonized, in that manner of his which is so familiar, against other draperies of dark crimson and pale olive. Nothing need be said in praise of the drawing of this figure, in the difficulties of which the artist has evidently found one of his chief pleasures; for problems of drawing are child’s play to him.”

THE INSTALLATION AT THE F RICK : LEIGHTON , WHISTLER , AND AESTHETICISM

Leighton and Whistler — near exact contemporaries — were two of the most prominent figures in the London art world in the late nineteenth century . They cultivated widely disparate artistic identities at a time of increasingly emphatic division between the academic and the avant- arde in Europe. Following traditional methods, Leighton produced meticulously painted canvases with a high degree of finish. By contrast, Whistler embraced a distinctly modern manner, employing free brushwork, thin veils of paint, and deliberately flattened forms. While Leighton was an exceptionally private man whose presidency of the increasingly outmoded Royal Academy shaped his public persona, Whistler was vocal, openly combative, and well known for his eccentricities and anti - establishment sentiments.

Nevertheless , in spite of their disparate methods and reputations, the two men shared deeply rooted — and radical — artistic principles, as important proponents of Aestheticism. Underpinned by the concept of “art for art’s sake” — the belief in the independent value of art apart from any didactic, moral, or political purpose — Aestheticism called for the prioritization of formal qualities of color and line over subject matter. Both Leighton and Whistler created Aesthetic masterpieces in which color and line are indeed primary, yet also serve to evoke mood or character. A comparison of Leighton’s Flaming June — a painting of an anonymous figure freed from any narrative context or specificity of time and place — and

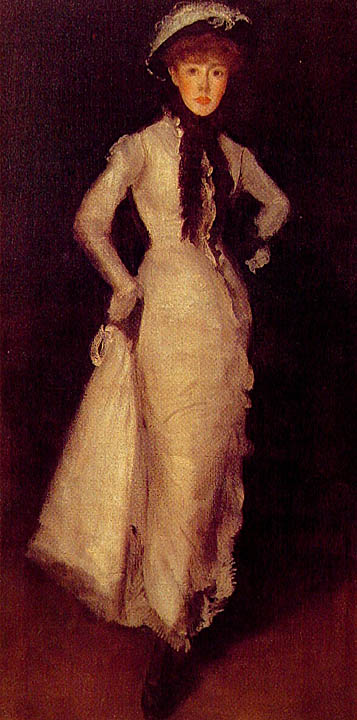

Whistler’s Harmony in Pink and Grey: Portrait of Lady Meux — a commissioned portrait of a member of high society — reveals these shared aims. Both works explore the dual impact of the beauty of the female body and the visual power of color. The two images — one a voluptuou s woman who stares suggestively at the viewer, the other a sleeping beauty in the presence of a poisonous flower — draw on the archetype of the femme fatale. In both, the body is submitted to abstraction, becoming a dynamic play of angles and curves, while remaining a palpable presence. In Flaming June, the model’s limbs are elongated and arranged to form a spiral within a perfectly square canvas, while the serpentine line of Lady Meux’s body is accentuated by her costume — a tight - fitting satin waistcoat and a train with a chiffon ruffle that cascades to the ground in rhythmic folds. The paintings make their sensory impact through this combination of pure form and the sensuality of the body.

A MASTERPIECE REDISCOVERED

Flaming June’s journey to the Caribbean is no less colorful than the painting itself. Having passed through the hands of more than one private collector in the early years of the twentieth century, the painting was forgotten for a period of time, only to be rediscovered in 1962 behind the false panel of a chimneypiece in a house on the outskirts of London. Quickly passing through the hands of several individuals, it was purchased that same year by Jeremy Stephen Maas, adealer credited with rehabilitating Victorian art, which, since the early year s of the twentieth century, had fallen out of favor. It was in Maas’s London gallery that the painting was seen by Luis A. Ferré, the forward - looking founder of the Museo de Arte de Ponce, and the art historian René Taylor, the museum’s first director, who were in the process of building the collection. (The museum was founded in 1959.) Ferré said that he “fell in love with Flaming June on first sight.” He acquired other works by nineteenth - century British artists, creating one of the greatest assemblage s of Victorian art outside of England, a collection in which Leighton’s masterpiece reigns supreme.

PUBLICATION

The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated catalogue written by Susan Grace Galassi, Senior Curator at The Frick Collection, and Pablo Pérez d’Ors, Associate Curator of European Art at the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. The book (paperback, 56 pages, 26 illustrations; $14.95, members $13.46) will be available in the Museum Shop or can be ordered through the Frick’s Web site ( www.frick.org ) and by phone at 212.547.6848.

Credits:

1. Frederic Leighton Flaming June , ca. 1895 Oil on canvas 46 7/8 x 46 7/8 inches Museo de Arte de Ponce, The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc.

2. Frederic Leighton Sketch for “Flaming June,” 1894 – 95 Oil on can vas 4 ½ x 4 5/16 inches Private Collection, Courtesy of Nevill Keating Pictures

3 . James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903) Harmony in Pink and Grey: Portrait of Lady Meux , 1881 – 82 Oil on canvas 76 ¼ x 36 5/8 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

4 . James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903) Symphony in Flesh Colour and Pink: Portrait of Mrs Frances Leyland , 1871 – 74 Oil on canvas 77 1/8 x 40 ¼ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

5 . James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903) Arrangement in Black and Gold: Comte Robert de Montesquiou - Fezensac , 1891 – 92 O il on canvas 82 1/8 x 36 1/8 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

6. James Abbott McNeill Whistl e\r (1834 – 1903) Arrangement in Brown and Black: Portrait of Miss Rosa Corder, 1876 - 78 Oil on canvas (lined) 75 ¾ x 36 3/8 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

PUBLICATION

The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated catalogue written by Susan Grace Galassi, Senior Curator at The Frick Collection, and Pablo Pérez d’Ors, Associate Curator of European Art at the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. The book (paperback, 56 pages, 26 illustrations; $14.95, members $13.46) will be available in the Museum Shop or can be ordered through the Frick’s Web site ( www.frick.org ) and by phone at 212.547.6848.

Credits:

1. Frederic Leighton Flaming June , ca. 1895 Oil on canvas 46 7/8 x 46 7/8 inches Museo de Arte de Ponce, The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc.

2. Frederic Leighton Sketch for “Flaming June,” 1894 – 95 Oil on can vas 4 ½ x 4 5/16 inches Private Collection, Courtesy of Nevill Keating Pictures

3 . James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903) Harmony in Pink and Grey: Portrait of Lady Meux , 1881 – 82 Oil on canvas 76 ¼ x 36 5/8 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

4 . James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903) Symphony in Flesh Colour and Pink: Portrait of Mrs Frances Leyland , 1871 – 74 Oil on canvas 77 1/8 x 40 ¼ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

5 . James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903) Arrangement in Black and Gold: Comte Robert de Montesquiou - Fezensac , 1891 – 92 O il on canvas 82 1/8 x 36 1/8 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

6. James Abbott McNeill Whistl e\r (1834 – 1903) Arrangement in Brown and Black: Portrait of Miss Rosa Corder, 1876 - 78 Oil on canvas (lined) 75 ¾ x 36 3/8 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb

Study for Leighton’s Flaming June Re-emerges After 120 Years

The only known head study for one of the most famous masterpieces of the nineteenth century has re - emerged 120 years after it was last reproduced in an art magazine in 1895. The important rediscovery of pencil and white chalk study for Frederic, Lord Leighton’s Flaming June, provides the missing link in the preparatory work for the painting that has become known as ‘The Mona Lisa of the Southern Hemisphere’. Estimated at £ 40,000 - 6 0,000, the drawing will be offered for sale at Sotheby’s in London this summer.

The only known head study for one of the most famous masterpieces of the nineteenth century has re - emerged 120 years after it was last reproduced in an art magazine in 1895. The important rediscovery of pencil and white chalk study for Frederic, Lord Leighton’s Flaming June, provides the missing link in the preparatory work for the painting that has become known as ‘The Mona Lisa of the Southern Hemisphere’. Estimated at £ 40,000 - 6 0,000, the drawing will be offered for sale at Sotheby’s in London this summer.

Simon Toll, Sotheby's Victorian Art specialist, commented: "I discovered the drawing hanging behind the door in Lady Roxburghe's bedroom at West Horsley Place and immediately realised I was looking at t he original of the drawing that is illustrated in the Magazine of Art from 1895. This head study for the painting is the last piece of the jigsaw in terms of the preparatory work Leighton undertook before starting on the big oil painting. Both the nude and the drapery studies for the figure are known and accounted for, as is the oil sketch formerly in the Leverhulme collection and sold by Sotheby's in 2001. It is a thrilling find, one of the most heart - stopping moments in my career."

Painted in 1895, Flaming June is now internationally famous, but this has not always been the case. Like the drawing, the painting was lost from sight for many years. Leighton was at the height of his career when in 1895 he exhibited Flaming June at the Royal Academy, where it met with an enthusiastic reception. The picture was loaned for some years to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, returned to its owner in 1930, sold shortly afterwards and subsequently lost for more than 30 years. It reappeared in 1963 on a market trader’s stall in Chelsea with little fanfare , selling to a London - based Polish frame maker for £50.

After changing hands a few times in quick succession, one owner being a hairdresser on Albemarle Street with a side - line in selling pictures, it was bought by art dealer Jeremy Maas, a pioneer in re-establishing the reputation of many painters of the Victorian era who illustrated the front cover of his book Victorian Painters with a colour image of the work, in recognition of Flaming June’s deserving of iconic status .

With British interest in Victorian art at its lowest ebb since the height of the Victorian Empire, the painting was purchased by Luis Ferre, then the Governor of Puerto Rico. It is now a highlight of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Ponce.

The drawings produced by Leighton illustrate and explain his methods as a painter. In the preparatory drawings for Flaming June he was not concerned with capturing the individual characteristics of his subject, but with realising an ideal – not just one of beauty, which was a natural attribute of his model, but also of pose, expression and overall composition. Leighton kept his drawings in drawer s and often referred to them, singling out individual sheets, choosing poses, revising themes .

There has been some debate regarding the model for Flaming June. Traditionally she has been identified as Dorothy Dene, Leighton’s favourite professional model in the 1880s. In the early 1890s, however, another beautiful woman’s face became prominent in Leighton’s work, that of Mary Lloyd, whose classical and striking looks ensured her popularity among Leighton and his peers. Lloyd maintained her ‘respectability’ by only posing clothed. It is likely that both identifications are accurate and that Mary Lloyd posed for the head and Dorothy Dene posed for the figure Almost ever since Flaming June turned up on the market stall, collectors have been lamenting their missed opportunity to buy for a fraction of itstrue worth one of the most famous of all Victorian paintings. The re-appearance of this study is no small recompense for that loss.

Painted in 1895, Flaming June is now internationally famous, but this has not always been the case. Like the drawing, the painting was lost from sight for many years. Leighton was at the height of his career when in 1895 he exhibited Flaming June at the Royal Academy, where it met with an enthusiastic reception. The picture was loaned for some years to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, returned to its owner in 1930, sold shortly afterwards and subsequently lost for more than 30 years. It reappeared in 1963 on a market trader’s stall in Chelsea with little fanfare , selling to a London - based Polish frame maker for £50.

After changing hands a few times in quick succession, one owner being a hairdresser on Albemarle Street with a side - line in selling pictures, it was bought by art dealer Jeremy Maas, a pioneer in re-establishing the reputation of many painters of the Victorian era who illustrated the front cover of his book Victorian Painters with a colour image of the work, in recognition of Flaming June’s deserving of iconic status .

With British interest in Victorian art at its lowest ebb since the height of the Victorian Empire, the painting was purchased by Luis Ferre, then the Governor of Puerto Rico. It is now a highlight of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Ponce.

The drawings produced by Leighton illustrate and explain his methods as a painter. In the preparatory drawings for Flaming June he was not concerned with capturing the individual characteristics of his subject, but with realising an ideal – not just one of beauty, which was a natural attribute of his model, but also of pose, expression and overall composition. Leighton kept his drawings in drawer s and often referred to them, singling out individual sheets, choosing poses, revising themes .

There has been some debate regarding the model for Flaming June. Traditionally she has been identified as Dorothy Dene, Leighton’s favourite professional model in the 1880s. In the early 1890s, however, another beautiful woman’s face became prominent in Leighton’s work, that of Mary Lloyd, whose classical and striking looks ensured her popularity among Leighton and his peers. Lloyd maintained her ‘respectability’ by only posing clothed. It is likely that both identifications are accurate and that Mary Lloyd posed for the head and Dorothy Dene posed for the figure Almost ever since Flaming June turned up on the market stall, collectors have been lamenting their missed opportunity to buy for a fraction of itstrue worth one of the most famous of all Victorian paintings. The re-appearance of this study is no small recompense for that loss.

.jpg)