Museo Correr of Venice

May 1, 2015-August 30, 2015

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

October 4, 2015–January 17, 2016

Germany’s Weimar Republic, established between the end of World War I and the Nazi rise to power, was a thriving laboratory of art and culture. As the country experienced unprecedented and often tumultuous social, economic, and political upheaval, many artists rejected Expressionism in favor of a new realism to capture this emerging society. Dubbed Neue Sachlichkeit—New Objectivity—its adherents turned a cold eye on the new Germany: its desperate prostitutes, crippled war veterans, and alienated urban landscapes, but also its emancipated New Woman, modern architecture, and mass-produced commodities.

New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933 is the first comprehensive exhibition in the United States to explore the dominant artistic trends of this period. Organized around five thematic sections and featuring 150 works by more than 50 artists, the exhibition mixes painting, photography, and works on paper to bring them into a visual dialogue. Key figures of modernism, such as Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, August Sander, and Christian Schad are featured alongside lesser-known artists such as Aenne Biermann, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Hans Finsler, Carl Grossberg, Lotte Jacobi, Alexander Kanoldt, and Georg Schrimpf.

Carl Grossberg, a Bauhaus-trained painter specialized in making industrial machinery look menacing and beautiful. “New Objectivity” includes Grossberg’s

Paper Machine (1934)

Yellow Boiler (1933).

This exhibition was organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in association with Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia and supported in part by the Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne, the Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation, Philippa Calnan and Suzanne Deal Booth.

More images:

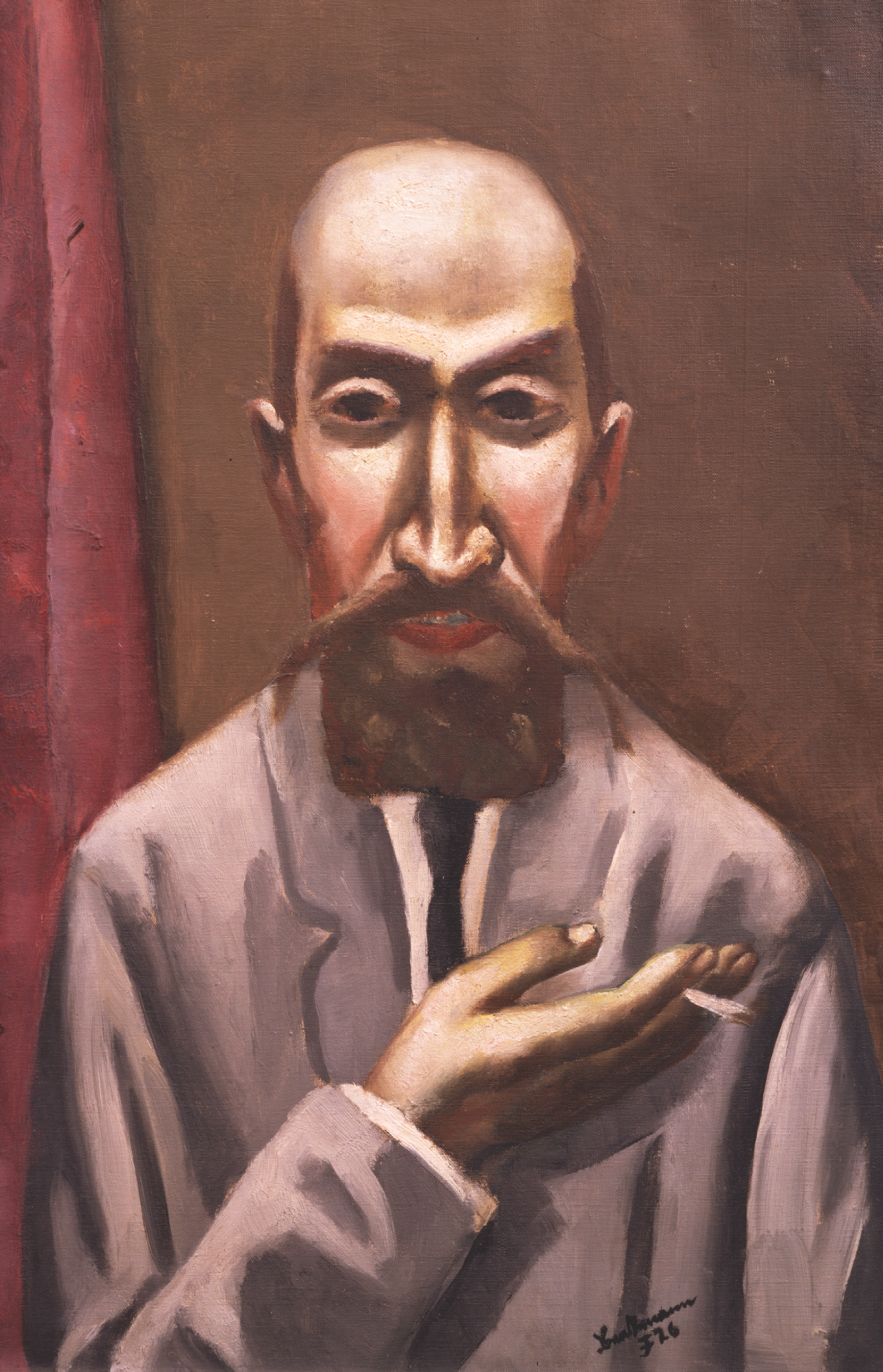

Max Beckmann “Portrait of a Turk”, 1926, Richard L. Feigen © Max Beckmann, by SIAE 2015

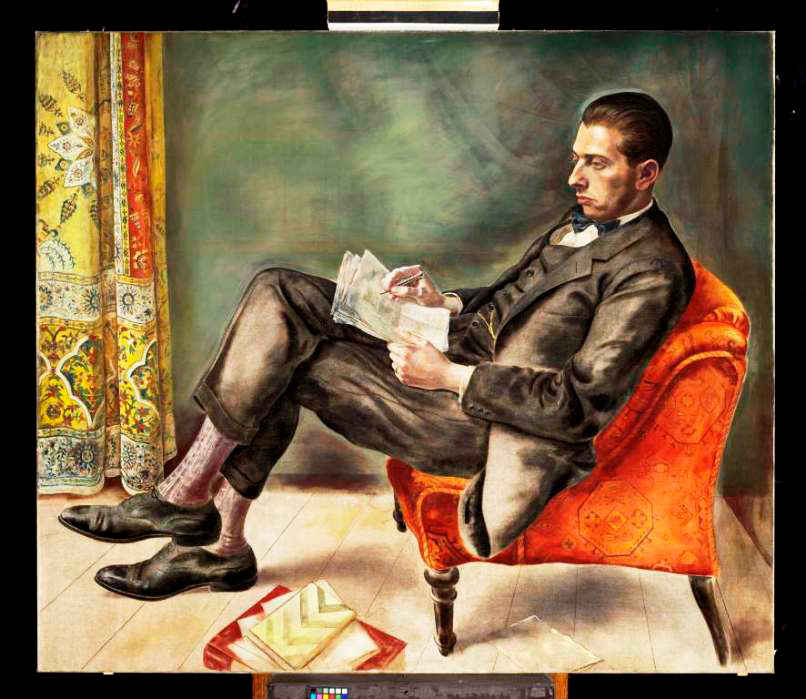

George Grosz Portrait of Dr. Felix J. Weil, 1926

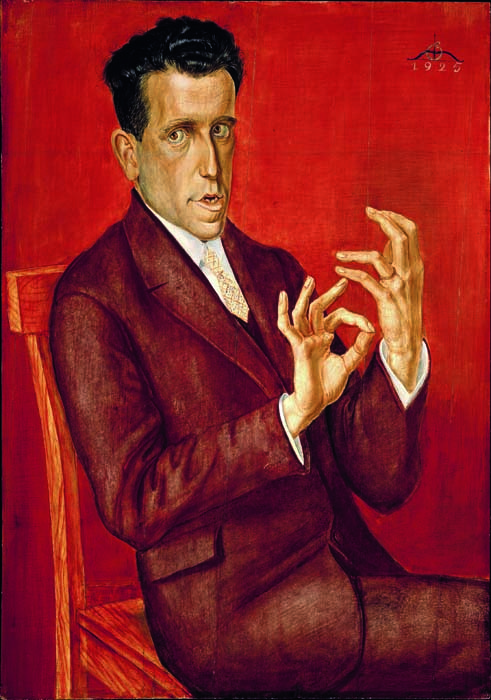

Otto Dix, Portrait of the Lawyer Hugo Simons, 1925, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.© Otto Dix, by SIAE 2015– The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

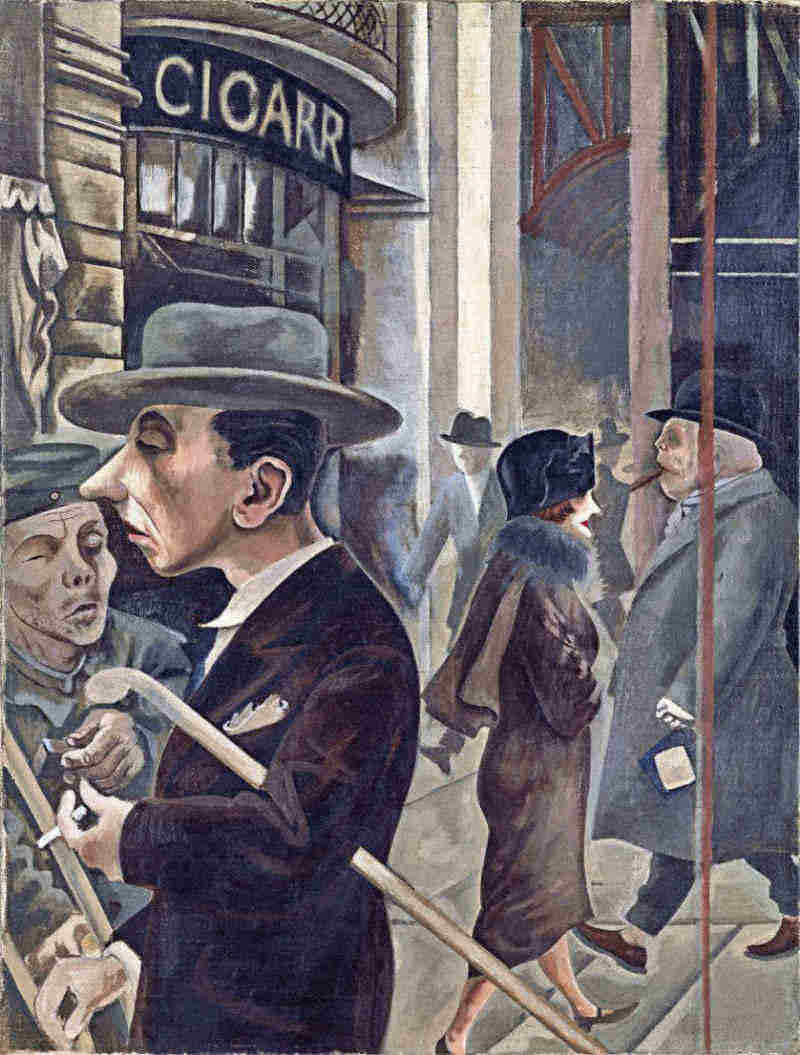

Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, The Profiteer (Der Schieber), 1920–21, Oil on canvas, Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf, © 2014 Renata Davringhausen, photo © 2014 Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast—ARTOTHEK

Publication

New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic 1919-1933

by Stephanie Barron (Editor), Sabine Eckmann (Editor), Christian Fuhrmeister (Contributor), Keith Holz (Contributor), Andreas Huyssen (Contributor), Maria Makela (Contributor), Olaf Peters (Contributor), James Van Dyke (Contributor), Matthew S. Witkovsky (Contributor), Graham Bader (Contributor), Daniela Fabricius (Contributor), Megan Luke (Contributor), Lynette Roth (Contributor), Pepper Stetler (Contributor), Nana Bahlmann (Contributor), Lauren Bergman (Contributor)

From an outstanding review in Financial Times: (Images added)

Max Beckmann “Lido”, 1924, Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May © Max Beckmann by, SIAE 2015

Two women pass each other on a sunless beach. One is veiled, the other is concealed beneath a white cloche hat and a cape with a jester’s jagged red fringe. Behind them, the limbs, heads, hands of bathers, chunky, disproportioned, ill-co-ordinated, jut out of green waves at odd angles. Composed in the colours of the Italian flag, Max Beckmann’s giddy, disquieting “Lido” returns to Venice 90 years after it was painted on an Adriatic holiday during the early rule of Mussolini. Beckmann said he wanted to depict “beautiful women and grotesque monsters”. Is “Lido” a carnival, an apocalypse or, as Berlin collector Curt Glaser wrote at the time, “a fantasy of the real”?...

Many of the Correr’s star turns have long been icons of social breakdown, disillusion and political rage. These range from the public —

George Grosz “Street Scene”, 1925, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid © George Grosz, by SIAE 2015

George Grosz’s “Street Scene (Kurfürstendamm)”, with its contrasting razor-sharp figures of gaunt war cripple and obese, cigar-puffing profiteer — to the private:

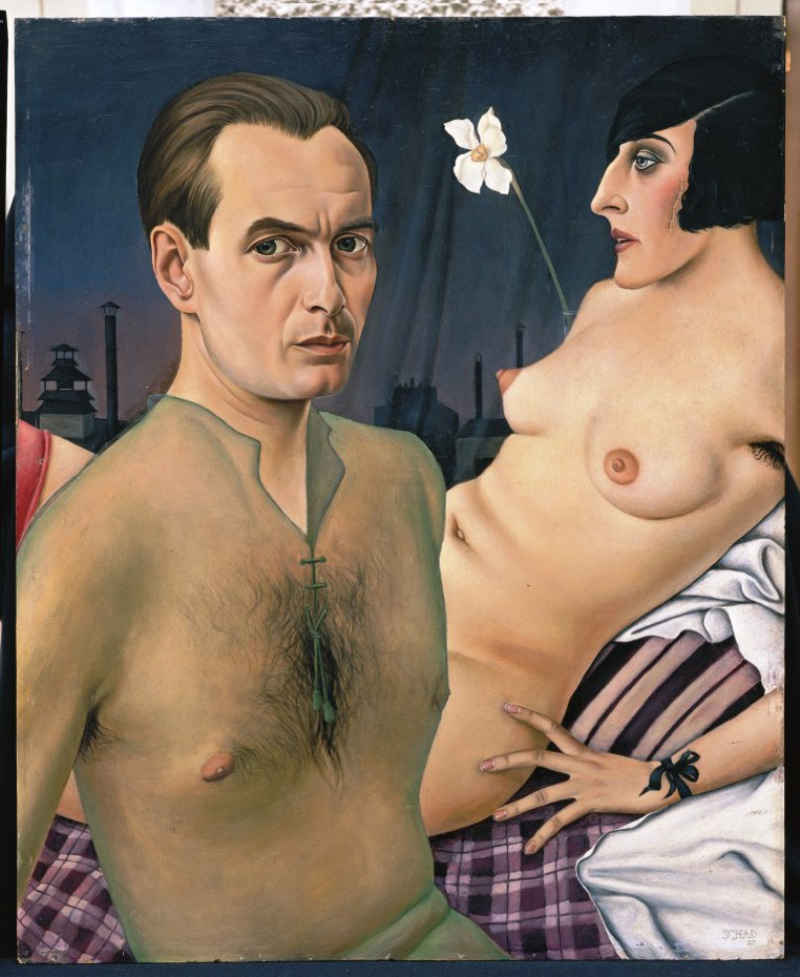

Christian Schad, Selfportrait, 1927, Private Collection, Loan by Courtesy of Tate Gallery London. © Bettina Schad, Archiv U. Nachlab & Christian Schad, by SIAE 2015;

Christian Schad’s anatomy of narcissism “Self-portrait with Model”, where the artist in transparent green shirt sits sullenly indifferent to the nude sharing his bed. Schad draws attention to her spidery fingers, dirty pink-polished nails, scarred face; at her shoulder, the single stalk of a large narcissus indicates both figures’ self-containment.