8 November 2013 – 23 February 2014

Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland

The first and second decade of the 20th century witnessed an unprecedented explosion of artistic movements all over Europe. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 brought much of this creative ferment to an abrupt end. At a time when politics sought to stoke enmity between Germany and France, artists exchanged ideas and collaborated across national borders with unprecedented intensity. Paris was the centre of the new art, yet it found its most enthusiastic early advocates in Germany.

The exhibition is the first to investigate and present in depth the fate of modern art in the context of the First World War by presenting some 300 works from around 60 artists.

The exhibition starts with two paintings by Lovis Corinth with a symbolic content: a bellicose

![]()

Self-portrait in Armour dating from 1914, and,

![]()

from 1918, the Pieces of Armour in the Studio, bereft of all but artistic purpose.

Before 1914:

The first section of the exhibition investigates the way different artists related to the war. Even before 1914, artists in Germany and Austria – for example Alfred Kubin, Ludwig Meidner and Oskar Kokoschka – had given visual expression to disturbing apocalyptic thoughts. Other artists like Ernst Barlach, Franz von Stuck, Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Luigi Russolo or Gino Severini indulged in manifold images of fighting.

From the Studio to the Battlefield:

The collapse of the newly-built edifice of international artistic exchange and collaboration dealt Modernism a decisive and tragic blow. Many artists left their studios for the battlefields, some – among them Umberto Boccioni, Franz Marc, August Macke, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Albert Weisgerber – never returned. International artists’ groups disbanded because the former guests had become ‘enemy aliens’ and had to leave the host country: Kandinsky went back to Russia, Kahnweiler was forced to leave France, Chagall could not return to Paris, the Delaunays fled to neutral Spain etc. In 1915 Marcel Duchamp, who had gone to New York, wrote ‘Paris is like a deserted mansion. Her lights are out. The friends are all away at the front. Or else they have already been killed.’

‘Avant-garde in uniform’:

While artists such as Franz Marc, André Mare and Dunoyer de Segonzac used avant-garde forms in the design of military camouflage, Kazimir Malevich in Russia, Raoul Dufy in France, Max Liebermann in Germany produced patriotic pictures.

Severe Traumatisation:

The third section of the exhibition looks at the severe traumatisation of many artists within months of the outbreak of the war. The existential experience of suffering and destruction led painters and graphic artists such as Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Dix or Egon Schiele – even Paul Klee – to poignant new themes and novel techniques. It was during the first year of the war that Franz Marc collected the motifs for a future pictorial world. Félix Vallotton, Frans Masereel and Willy Jaeckel created graphic series.

Prospects for the 20th century 1915–1918:

In 1916, with the war still raging across Europe, a group of émigré artists in neutral Switzerland founded the Cabaret Voltaire, the birthplace of Dada, that international protest movement against absolutely everything. At that time Duchamp was already working on his Large Glass. In 1917 Guillaume Apollinaire called for an esprit nouveau as the epitome of culture shaking off the fetters of the old and coined the term surrealism. Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich approached the complete abstraction. Thus it was during the war – outside its direct sphere of influence – that major perspectives for 20th century art were developed.

More on the exhibition:

The Avantgarde Prior to 1914 A Golden Age

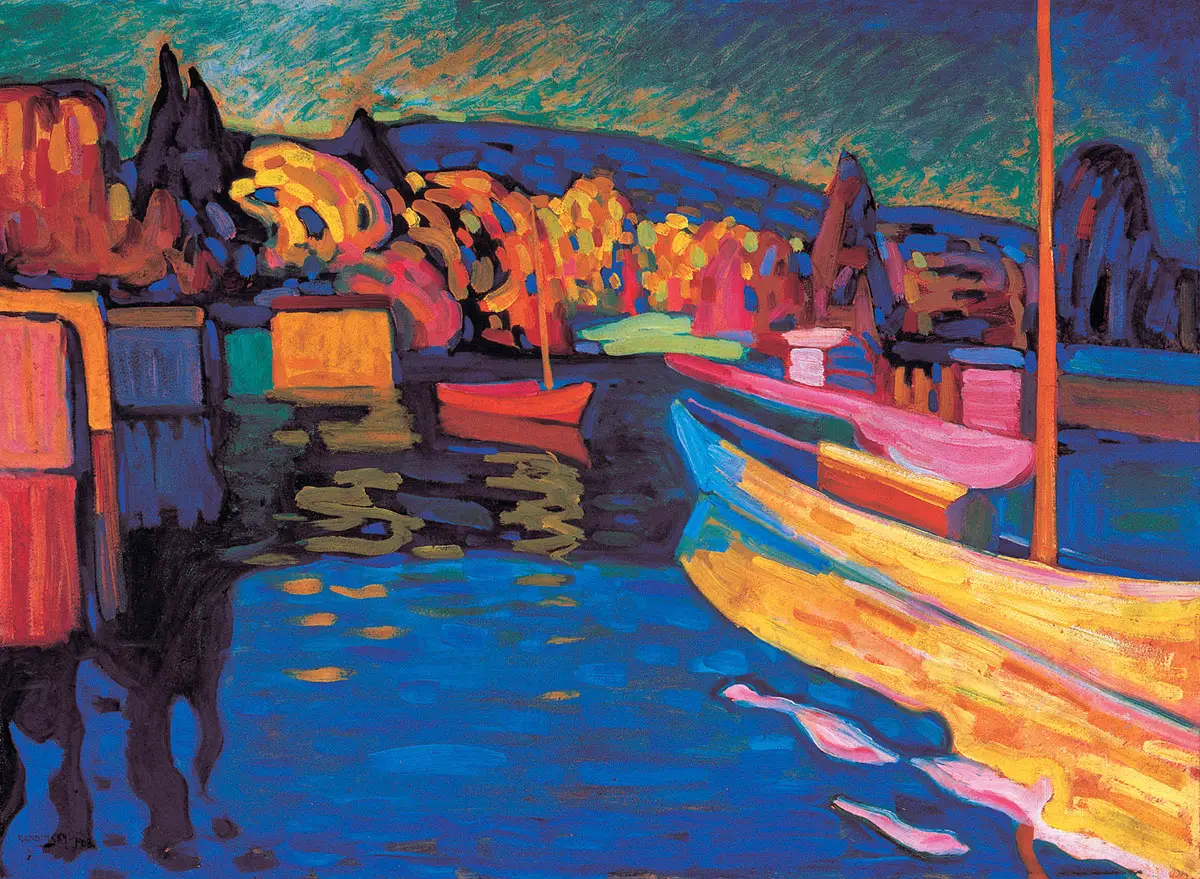

The years immediately prior to the outbreak of the First World War were the golden age of the international avantgarde. In France, Picasso and Braque together developed a pictorial language of facetted forms: Cubism. In 1912 they added items from the everyday world, thus re-uniting artwork and reality. Unlike these artists, who because of the their German dealers, were regarded in France as boches (derogatory term for ‘Germans’) and thus as politically suspect, Gleizes and Metzinger painted Cubist works regarded as typically French. For Delaunay and Léger, the Cubist imagery was no longer an end in itself, but a means of coming to terms with the theme of the large modern city. The avantgarde tone in Germany was set by the Munich-based artist-group known as Der Blaue Reiter, whose members included Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter and Alexej von Jawlensky. In their works, unlike those by the Cubists, the expressivity of colours played a major role. At about the same time in Prague, Franti_ek Kupka arrived at a similar pictorial conclusion to Kandinsky – namely abstraction.

Premonitions

Even before 1914, the optimism of the avantgarde was alloyed with dark forebodings, the sense of standing at a turning point in history. The Austrian artist Alfred Kubin understood in masterly fashion how to give expression to these existential fears. His pictorial world is permeated by fantastically combined incarnations of the menacing and demonic. With his apocalyptic landscapes, Ludwig Meidner added an unmistakable note to the eschatological pessimism of the day. In the works he painted before the outbreak of the war, the world is coming to a noisy end: a preview of things to come. Jakob Steinhardt used the motif of the contemporary city to illustrate his view of the world. He presents it as a place not of gleaming modernity, but of dislocation and decline.

Encircled by Enemies

Feinde ringsum (Encircled by Enemies) the title of a sculpture by Franz von Stuck, is taken from a slogan uttered by Kaiser Wilhelm II in August 1914, and so this is also the title of this room, whose main theme is different meanings of the word ‘struggle’. Ernst Barlach’s Rächer (The Avenger)(below) together with the lithograph

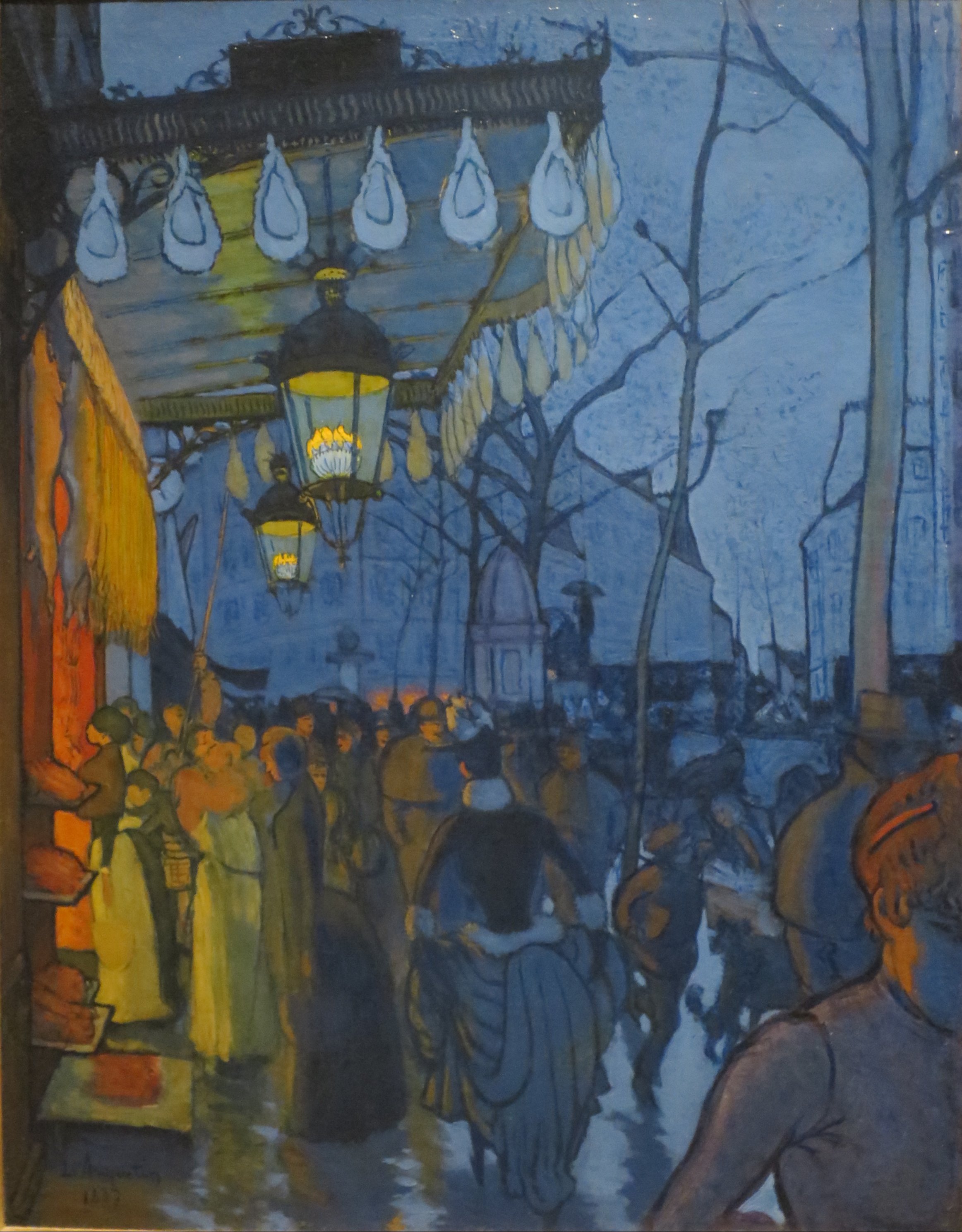

![]()

Der heilige Krieg (The Holy War),whose motif is the same, calls on Germans to honour their higher duty to the fatherland. Emil Nolde’s paintings, by contrast, display an altogether ambivalent relationship to the war. In the work of Roberto Baldessari and Gino Severini, we see a flaring up of the patriotic pathos of the Italian Futurists. The motif of the street decorated with flags, often to be seen in French painting of the time, and here illustrated by a work of Raoul Dufy, testifies at first to an – if anything – innocent patriotism, but as preparations for war got under way, takes on political significance. Kandinsky’s perspective was quite different: his apocalyptic scenes express the conviction that from the ruins of the old world, a new spiritual order would emerge.

Images and credits:

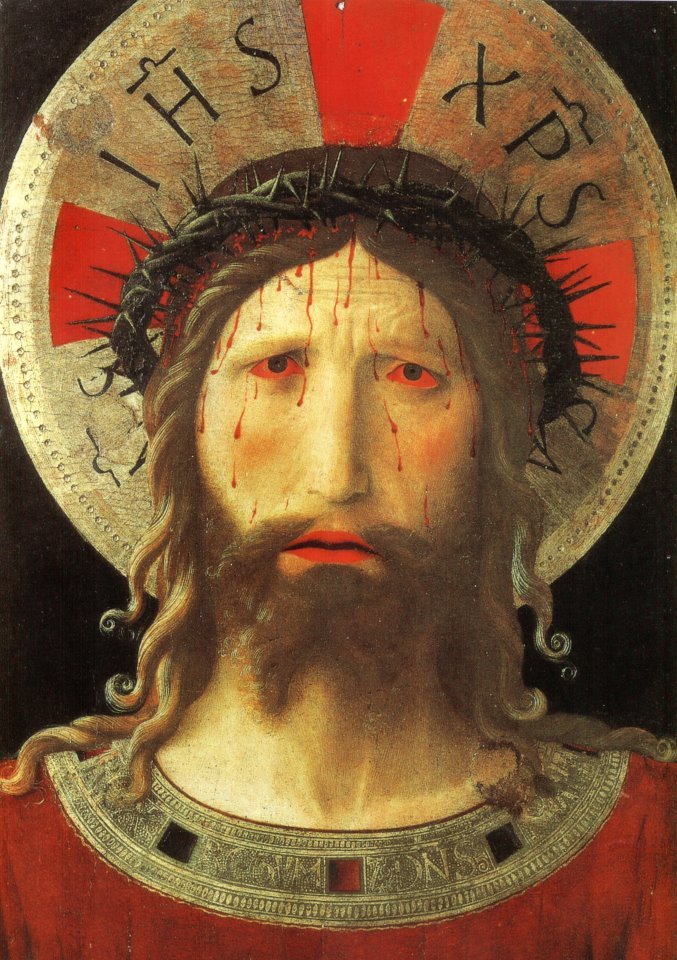

![]()

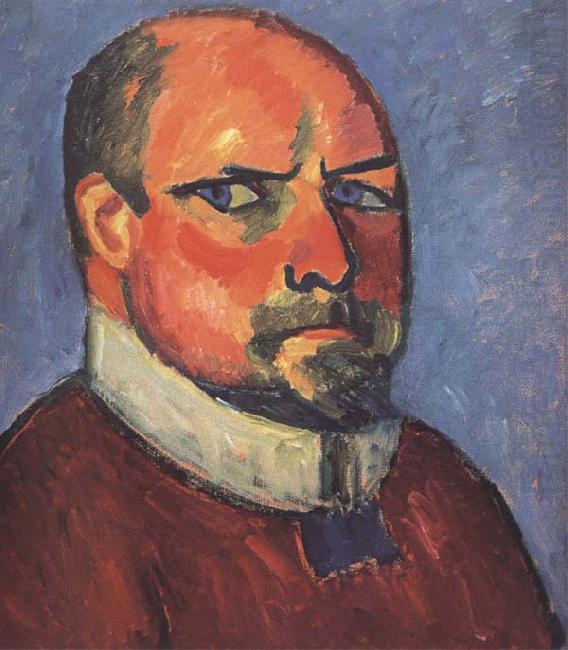

Alexej von Jawlensky

Self-portrait

1911, Oil on cardboard

© Stiftung im Obersteg, Depositum

im Kunstmuseum Basel

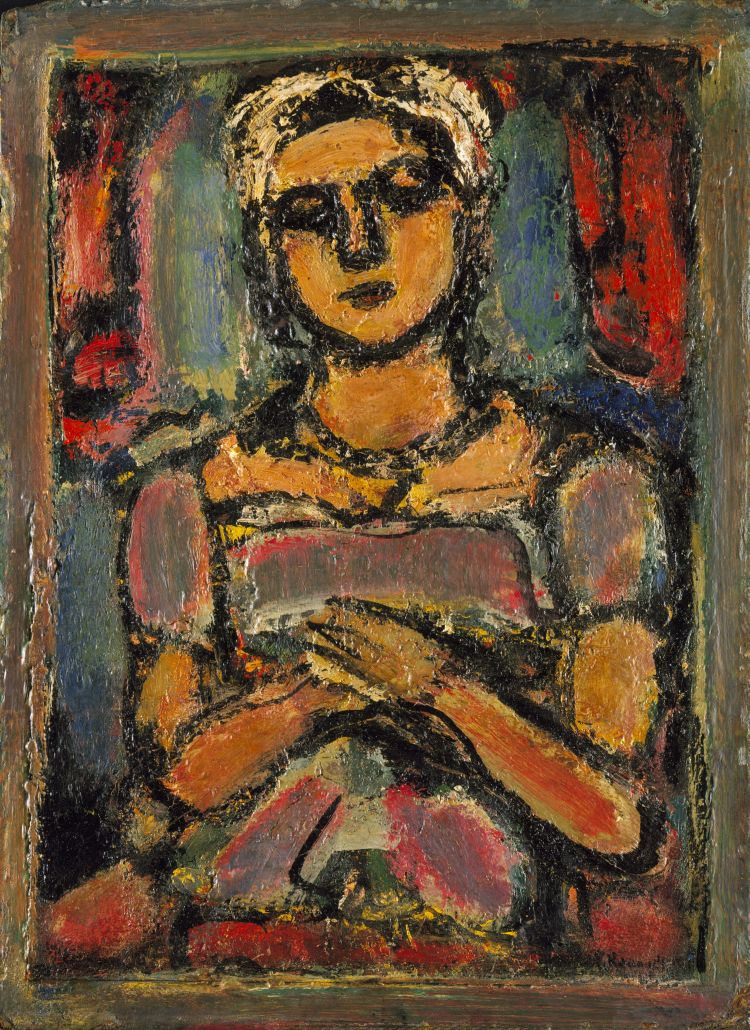

![]()

Ernst Barlach

The Avenger

1914, Bronze

Stiftung Saarländischer Kulturbesitz,

Saarland.Museum Saarbrücken

![]()

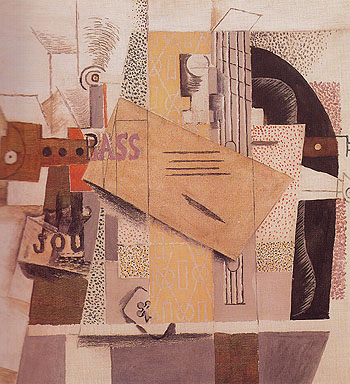

Pablo Picasso

The Violin

1914, Oil on canvas

© Musée national

d'art moderne Paris,

bpk/CNAC-MNAM

![]()

Emil Nolde

Soldiers, 1913

Oil on burlap

Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

![]()

Wassily Kandinsky

Deluge I

1912, oil on canvas

Kunstmuseen Krefeld

![]()

Ludwig Meidner

Burned-Out(Homeless)

1912

Oil on canvas

© Museum Folkwang

![]()

Ludwig Meidner

The Cannon (III)

1914

Pen and ink on paper

Winfried Flammann, Karlsruhe

1914. Into WarPatriotic, popular

Instead of standing at their easels in the studio, artists now served as soldiers at the front – or else on the ‘home front’. Thus at the outbreak of the war, the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky is said to have endlessly and publicly declaimed ‘bloodthirsty and virulently anti-German verses’ in Moscow. Such texts were also created for propaganda sheets designed by the Russians Kazimir Malevich and Aristarkh Lentulov in the style of the old Russian lubok or popular print. Vernacular images also inspired the French painter of serene landscapes Raoul Dufy, when in 1914 he drew coloured propaganda sheets in the style of the popular prints known as images d’Épinal.

The series of ‘artist flysheets’ that appeared from the end of August 1914 in Berlin under the title Kriegszeit (Time of War) were entirely in the spirit of the Kaiser’s war policy. Max Liebermann, August Gaul and Ernst Barlach all supplied numerous contributions. In Italy, Carlo Carrà helped to fire patriotic enthusiasm with his publication Guerrapittura (War Painting) in 1915.

Camouflage

When, during the war, Picasso saw a cannon painted in Cubist camouflage colours, he is said to have exclaimed: ‘That’s our doing!’ When artists were commissioned to design and implement camouflage patterns for ordnance, they applied their formal innovations. The sketchbooks of the Cubist André Mare bear particular witness to this. In France Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola headed the camouflage team to which the painters André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Roger de la Fresnaye, Jacques Villon and André Fraye belonged. On the German side, Franz Marc was assigned to paint camouflage. His letter, written in February 1916, gives more detailed information. In England artists such as Norman Wilkinson and Edward Wadsworth used confusingly entangled geometric forms for the ‘dazzle camouflage’ of naval vessels.

Images and credits:

![]()

Albert Weisgerber

David and Goliath

1914, Oil on Canvas

Stiftung Saarländischer Kulturbesitz,

Saarland.Museum, Saarbrücken

![]()

Kasimir Malewitsch

Look, oh look, the Vistula

is already close…

1914

Farblithografie

© Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin

![]() Max Liebermann

Max Liebermann

I no longer recognize any political partiesFrom: Kriegszeit. Künstlerflugblätter

Nr. 1 of 31 august 1914

Ed. by Paul Cassirer, 1914–16

Lithograph

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Bibliothek

![]()

Max Liebermann

Now we want to thrash them!From: Kriegszeit. Künstlerflugblätter

Nr. 2 of 7 september 1914

Ed. by Paul Cassirer, 1914–16

Lithograph

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Bibliothek

![]()

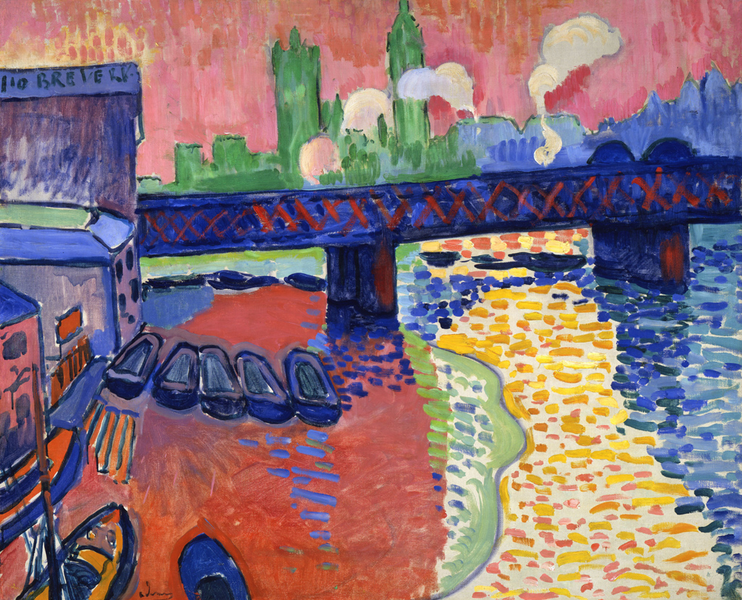

Raoul Dufy

The End of the Great War

1915

Coloured wood engraving

© Musée national d'art moderne Paris,

bpk/CNAC-MNAM

Shocks 1914/1915On the battlefield

Artists on active service often took the opportunity to make sketches on the spot: of strangers, of the sufferings of the victims, of destruction. In this way they took on the role of involved observers. These ‘brushless artists’ (Paul Klee) had to fall back on handy formats and simple techniques. As a rule these works were not commissioned, the artists themselves being driven to come to terms with the enormity of the events. By contrast, it was as an official Austrian war artist that Oskar Kokoschka made his sketches on the Isonzo front in summer 1916.

Where the artists did have access to easels, canvases and oil-paints, then they were mostly working on official commission, like the Frenchman Félix Vallotton and the Englishman C. R. W. Nevinson. If, as in Nevinson’s, case the motif did not accord with the political directives, the censorship authorities stepped in.

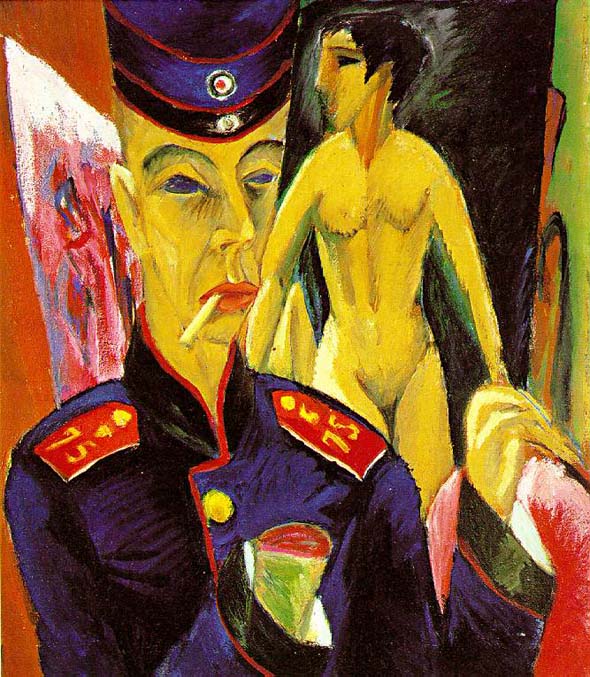

The disoriented, the wounded, the dead

At times the artists were not only observers, but depicted themselves as casualties. This was especially true of some German artists. In self-portraits, they come across as shattered, disoriented, frightened and confused. A particularly eloquent example is the painting by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

A unique artistic formulation for the general physical and psychological collapse was found by Wilhelm Lehmbruck. With his sculpture Der Gestürzte (Fallen Man) dating from 1916, which at first bore the title Sterbender Krieger (Dying Warrior), he created a kind of memorial.

Accusations

There were also artists who opposed the war from the outset. To reach as broad a public as possible, they plumped for prints as a medium. And to reinforce antiwar sentiment, they chose simple, hard-hitting images.

One of the first was the 26-year-old Willy Jaeckel, with his drastically realistic series of prints Memento 1914/15. After making sketches on the spot, the Impressionist Max Slevogt, who was a generation older, produced critical prints full of cartoon-like exaggeration. The Belgian Frans Masereel used the eyecatching succinct pictorial language of the black-and-white woodcut, as did the Frenchman Félix Vallotton for his own sheets, which banked on popular imagery.

A world of lines, shattered by reality

The terrors and fears of the war led some German artists to change their style, a change which went hand-in-hand with new motifs that bore the marks of their experiences.

Max Beckmann’s works from

![]()

Kriegserklärung (Declaration of War) to

![]()

Granatenexplosion (Shell Explosion) to

![]()

Leichenschauhaus (Morgue)

resemble stations along a road of suffering: direct witnesses to the shock he had undergone.

In the work of Otto Dix, too, the pictorial means reflect very directly the bewilderment felt in the face of the carnage, the explosion, and the ruins. Paul Klee’s drawings are invaded by prickly monsters; the very titles signal the menacing nature of the general situation.

Images and credits:

![]()

Otto Dix

Self-portrait as Mars

1915, Oil on canvas

© Städtische Sammlungen Freital, Schloss Burgk

![]() Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Self-portrait as a Soldier1915, Oil on canvas

© Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, USA

1914_lehmbruck.jpg

![]()

Max Slevogt

Die Kathedrale von Löwen

1914

Aquarell, Bleistift auf Papier

Stiftung Saarländischer Kulturbesitz,

Saarland.Museum, Saarbrücken aus der

Sammlung Kohl-Weigand

![]()

Édouard Vuillard

The Interrogation, 1917

Distemper on paper on canvas

Centre national des arts plastiques, Frankreich

Prospects for the Twentieth Century 1915–1918Fresh start in the studio

After the collapse, the artists rediscovered themselves as isolated individuals. To the extent that they could work in the studio at all, they made a fresh start with their art. The extreme experiences they had undergone demanded decidedly more radical means.

George Grosz now demanded ‘Brutality! Clarity that hurts!’, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner wrote: ‘I am inwardly riven and immunized against everything, but I am fighting to express this too through art.’ His pen-and-ink drawing are among the most impressive examples of graphic art in the whole twentieth century.

A new pictorial world also opened up for Paul Klee in the years 1916/17. On an experimental basis to start with, he laid the artistic foundation for his future oeuvre. Max Beckmann’s radical new start in painting is immediately obvious when one compares the two self-portraits, the one before, the other immediately after his involvement in the war. The large, unfinished (and not for loan) Auferstehung (Resurrection) is the subjective résumé of his war experience.

Against everything: Dada

When artists formed groups during the war, they were driven by the political conditions. Some fled to avoid mobilization, some travelled on false passports, some deserted. Neutral Switzerland was the venue in 1915/16 for opponents of, and refugees from the war, such as the Romanians Marcel Janco and Tristan Tzara, the Germans Hans Richter, Richard Huelsenbeck, Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings, and Hans Arp, who was from Alsace. Richter noted that he could not understand ‘how a movement could arise from such heterogeneous elements’. This movement was Dada.

The Dadaists were against everything, against the war, against the bourgeoisie and against its culture. Their activities in Zurich were concentrated three areas: a new approach to spoken language, a new approach to printed language (typography) and the invention of the ‘Aktion’ as an art form.

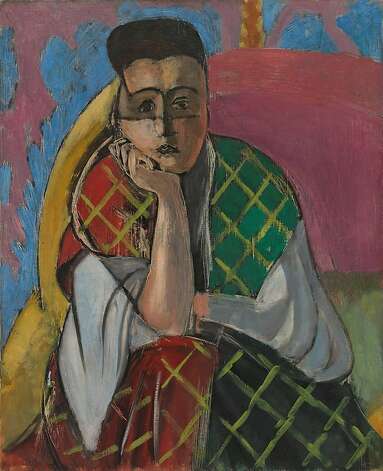

![]()

Max Beckmann

Self-portrait as a Medical Orderly

1915, Oil on canvas

© Von der Heydt Museum Wuppertal

Max Beckmann

![]()

Paul Klee

Stars above Evil Houses

1916

Watercolor on plaster-primed canvas,

mounted on cardboard

© Merzbacher Kunststiftung

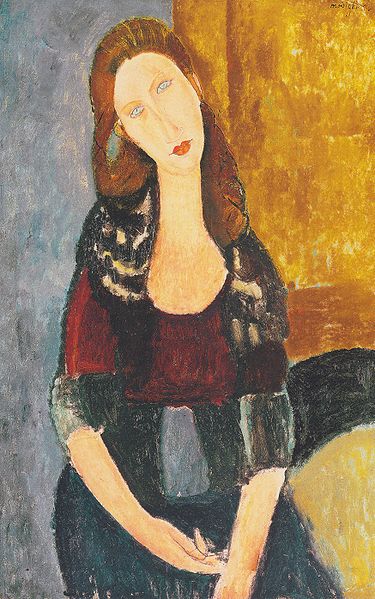

![]()

Egon Schiele

Portrait of the Artist’s Wife

1917, Oil on canvas

© The Pierpont Morgan Library New York

![]()

Radicalized Modernism

Malevich presented his totally abstract Black Square for the first time in Petrograd (St Petersburg) in 1915. At the same time, Vladimir Tatlin exhibited sculptures made of objets trouvés that represent nothing but themselves. This laid the foundations for unconditional abstraction and for the material picture of the twentieth century.

In order to escape the war, Marcel Duchamp went to New York in the summer of 1915. Here he created The Large Glass, and applied the term ‘Ready-made’ for the first time to his selected objects – the foundations of Concept Art. While Picasso, after 1915, was once again working in the traditional style, which he had previously rejected in favour of the Cubist technique, the Paris-based Futurist Severini also made a similar turnaround, thus laying the foundations for the Neue Sachlichkeit of the 1920s.

To avoid military service, Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà both spent time in a military psychiatric hospital in Ferrara in 1917. There they produced outstanding works which paved the way for Surrealist painting.

List of ArtistsPierre ALBERT-BIROT (1876–1967)

Hans (Jean) ARP (1886–1966)

Roberto Marcello Iras BALDESSARI (1894–1965)

Hugo BALL (1886–1927)

Ernst BARLACH (1870–1938)

Max BECKMANN (1884–1950)

Carlo CARRÀ (1881–1966)

Lovis CORINTH (1858–1925)

Robert DELAUNAY (1885–1941)

Otto DIX (1891–1969)

Marcel DUCHAMP (1887–1968)

Raoul DUFY (1877–1953)

Heinrich EHMSEN (1886–1964)

Conrad FELIXMÜLLER (1897–1977)

André FRAYE (1887–1963)

August GAUL (1869–1921)

Albert GLEIZES (1881–1953)

Walter GRAMATTÉ (1897–1929)

Rudolf GROSSMANN (1882–1941)

George GROSZ (1893–1959)

Otto GUTFREUND (1889–1927)

Raoul HAUSMANN (1886–1971)

Erich HECKEL (1883–1970)

Otto HETTNER (1875–1931)

Richard HUELSENBECK (1892–1974)

Willy JAECKEL (1888–1944)

Marcel JANCO (1895–1984)

Alexej von JAWLENSKY (1865–1941)

Arthur KAMPF (1864–1950)

Wassily KANDINSKY (1866–1944)

Ernst Ludwig KIRCHNER (1880–1938)

Paul KLEE (1879–1940)

Oskar KOKOSCHKA (1886–1980)

Käthe KOLLWITZ (1867–1945)

Alfred KUBIN (1877–1959)

Franti_ek KUPKA (1871–1957)

Fernand LÉGER (1881–1955)

Wilhelm LEHMBRUCK (1881–1919)

Aristach LENTULOW (1882–1943)

Max LIEBERMANN (1847–1935)

August MACKE (1887–1914)

Wladimir Wladimirowitsch MAJAKOWSKI (1893–1930)

Kazimir MALEVICH (1878–1935)

Franz MARC (1880–1916)

André MARE (1885–1932)

Frans MASEREEL (1889–1972)

Ludwig MEIDNER (1884–1966):

Jean METZINGER (1883–1956)

Gabriele MÜNTER (1877–1962)

Christopher Richard Wynne NEVINSON (1889–1946)

Emil NOLDE (1867–1956)

Francis PICABIA (1879–1953)

Pablo PICASSO (1881–1973)

Hans RICHTER (1888–1976)

Waldemar RÖSLER (1882–1916)

Luigi RUSSOLO (1885–1947)

Egon SCHIELE (1890–1918)

Gino SEVERINI (1883–1966)

Max SLEVOGT (1868–1932)

Jacob STEINHARDT (1887–1968)

Wladimir Lewgrafowitsch TATLIN (1885–1953)

Wilhelm TRÜBNER (1851–1917)

Percyval TUDOR-HART (1873–1954)

Leon UNDERWOOD (1890–1975)

Henry VALENSI (1883–1960)

Félix VALLOTTON (1865–1925)

Theo VAN DOESBURG (1883–1931)

Franz VON STUCK (1863–1928)

Éduard VUILLARD (1868–1940)

Albert WEISGERBER (1878–1915)

Ossip ZADKINE (1891–1967)

Catalogue

1914. The Avant-Gardes at War

Format: 24,5 x 28 cm, Hardcover

Pages: 360 with 400 colour illustrations

Walther König

ISBN: 978-3-86442-052-8 (German)

ISBN: 978-3-86442-053-5 (English)

Texts by Régine Bonnefoit and Gertrud Held, Uwe Fleckner, Eckhart Gillen,

Christine Hopfengart, Lucian Hölscher, Friederike Kitschen, Joes Segal, Uwe M.

Schneede, Jay Winter and with biographiqual notes about the artists in the years

1914 till 1918 by Natascha Bolle

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/611px-Dar%C3%ADo_de_Regoyos_-_Vendredi_Saint_en_Castille_(Good_Friday_in_Castile)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg!Large.jpg)

_-_Prometheus_Bound_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/667px-Peter_Paul_Rubens,_Flemish_(active_Italy,_Antwerp,_and_England)_-_Prometheus_Bound_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

_-_Prometheus_-_KMSK_Brussel_25-02-2011_12-45-49.jpg/800px-Theodoor_Rombouts_(1597-1637)_-_Prometheus_-_KMSK_Brussel_25-02-2011_12-45-49.jpg)