American Primitive Paintings from the Collection of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch

Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art May 9 – July 11, 1954

More than 100 portraits, landscapes, still lifes, and genre paintings came from the Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch collection of early American paintings. Since 1944, Colonel and Mrs. Garbisch had assembled the largest private collection of American naive art, more than 1,800 examples, from the early 18th to the late 19th century. Their intention was that the collection would eventually be made available to the public through gifts and loans to museums here and abroad. This first exhibition of paintings was drawn from their first gift of 300 paintings and 200 miniatures. It was coordinated by William P. Campbell.

Robert Peckham, The Hobby Horse, c. 1840. Oil on canvas, 103.5 x 101.6 cm (40 3/4 x 40 in.). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch.

Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl, Family Portrait, 1804, oil on canvas, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1953.5.8

Catalog: American Primitive Paintings from the Collection of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, Part I. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1954.

One Hundred Eleven Masterpieces of American Naive Painting from the Collection of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch

111 paintings from the Garbisch collection were shown. For 25 years Colonel and Mrs. Garbisch had assembled a collection of 2,600 early American paintings for their country estate, "Pokety," in Cambridge, Maryland. 34 of the paintings that were exhibited had been given to the National Gallery, including

Linton Park, Flax Scutching Bee, 1885, oil on bed ticking, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1953.5.26

General Washington on A White Charger,

and The Peaceable Kingdom by Edward Hicks.

The exhibition was organized and circulated by the American Federation of Arts.

Catalog: American Naive Painting of the 18th and 19th Centuries: 111 Masterpieces from the Collection of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, preface by Lloyd Goodrich, introduction by Albert Ten Eyck Gardner. New York: American Federation of Arts, 1969.

Venues:

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, June 12 – September 1, 1969

Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, February 16–April 18, 1968

Amerika House, Berlin, May 3–June 10, 1968

Palazzo Collicola, Festival of the Two Worlds, Spoleto, June 28–July 14, 1968

Royal Academy of Arts, London, September 6–October 20, 1968

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, November 7–December 29, 1968

Cason del Buen Ritiro, Madrid, January 15–February 16, 1969

Palacio de la Virreina, Barcelona, February 21–March 16, 1969

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, March 24–April 27, 1969

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, June 12–September 1, 1969

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, November 16, 1969–January 4, 1970

United States Military Academy Library, West Point, January 22–February 15, 1970

American Naive Paintings from the National Gallery of Art

Venues

Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Connecticut, January 17 through May 31, 1998.

From a review of the Old Lyme show (including images):

These lively and engaging paintings from the late eighteenth through the nineteenth centuries include portraits, landscapes, history paintings, and scenes of daily life. Such well-known artists as Edward Hicks and Erastus Salisbury Field are represented as well as many painters whose names are not known. These works by largely self-taught artists demonstrate strong design in pleasing colors with a sense of vitality that is just as appealing today as when the works were created.

Farmhouse in Mahantango Valley, American 19th century

While their style has also been called "folk" or "primitive," these artists came from diverse backgrounds and demonstrated varying degrees of sophistication in their art. There were those who had some experience studying with academic painters or working with established studios such as Currier & Ives. Many were amateurs, drawing inspiration from instruction manuals or prints of the day. Several worked simultaneously as artisans in other fields. Others were successful itinerants, traveling through the rapidly growing towns, and countryside working predominantly in established population centers of the northeast.

Boy with Toy Horse and Wagon, William Matthew Prior

During the nineteenth century, the growing wealth and comfort of the American middle class created an expanding market of patrons interested in documenting their images for posterity. Before the spread of photography, they turned to such successful portrait painters as Joshua Johnson, Ammi Phillips, and William Matthew Prior. Many anonymous artists also produced records of family members, and a number of pictures in the exhibition relate to the history of Connecticut including a portrait of an early Stonington family by Denison Limner.

Elizabeth Denison, Denison Limner

While portraits represent the most popular and important segment of naive art, a variety of other themes are displayed in this exhibition including marine, still life, and genre paintings. In the aftermath of the Civil War, artists outside the academic tradition also interpreted historical and biblical events with fresh, expressive visions. Among those presented in the show are

Edward Hick's idyllic Penn's Treaty with the Indians (c. 1840-44).

American Folk Art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Venues

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, March 2, 1999 - January 2, 2000

New York State Museum, Albany, Feb. 11 to April 23, 2000

The biggest names in American folk art -- Rufus Hathaway, Edward Hicks, Joshua Johnson and Ammi Phillips -- were featured in American Folk Art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The more than 50 works from The Metropolitan Museum's distinguished collection of American folk art include portraits, landscapes and historical and religious scenes. Featured are such canonical works as

Lady with her Pets (1790) by Rufus Hathaway,

Peaceable Kingdom (ca. 1830-32) by Edward Hicks,

Falls of Niagara (1825) by Hicks

and Mrs. Mayer and Daughter (1835-1840) by Ammi Phillips.

The precise nature of folk art has long been the subject of debate among art historians, critics, folklorists and collectors. The artists may have acquired their skills through apprenticeship, observation or informal learning. Their work adheres to the aesthetic standards of the communities in which they worked.

This exhibition was organized by Carrie Rebora Barratt, Associate Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture and Manager of The Henry R. Luce Center for the Study of American Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

From a review of the New York City show (including images):

Rufus Hathaway (1770-1822) was only twenty years old when he painted Lady with her Pets (Molly Wales Forbes), one of the best-known portraits by an American country painter. There is no record of Hathaway having had any artistic training and his work shows very little stylistic development over time. Nonetheless, his oeuvre is memorable for its charm, a bold use of color, and mastery of two-dimensional design.

Paintings by Hathaway are rare after 1795, when he forsook this occupation to become a doctor. In Lady with her Pets - Hathaway's earliest known work - the attitude of the sitter, her herisson (or hedgehog-style coiffure), and the almost emblematic arrangement of her pets mimic contemporary French trends in fashion and portraiture, which Hathaway could have known through prints.

Orphaned at a very early age, Edward Hicks (1780-1849) was taken in by a family that raised him in the Quaker tradition. He was apprenticed to a coach maker and showed an early aptitude for painting, which led to employment as a painter of decorations on coaches and of street, shop, and tavern signs. Upon being accepted as a Quaker preacher - contemporary accounts note his extraordinary gifts in this regard - he felt compelled to give up these lucrative and worldly pursuits. He tried farming, but his debts mounted, his health declined, and he still had a family to support. Hicks resolved this dilemma by returning to painting, but focused solely on subject matter of a religious nature.

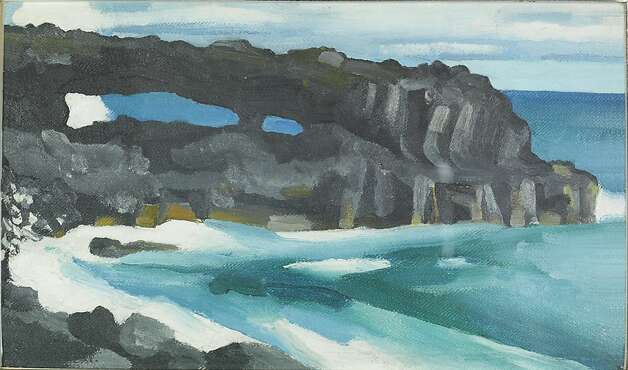

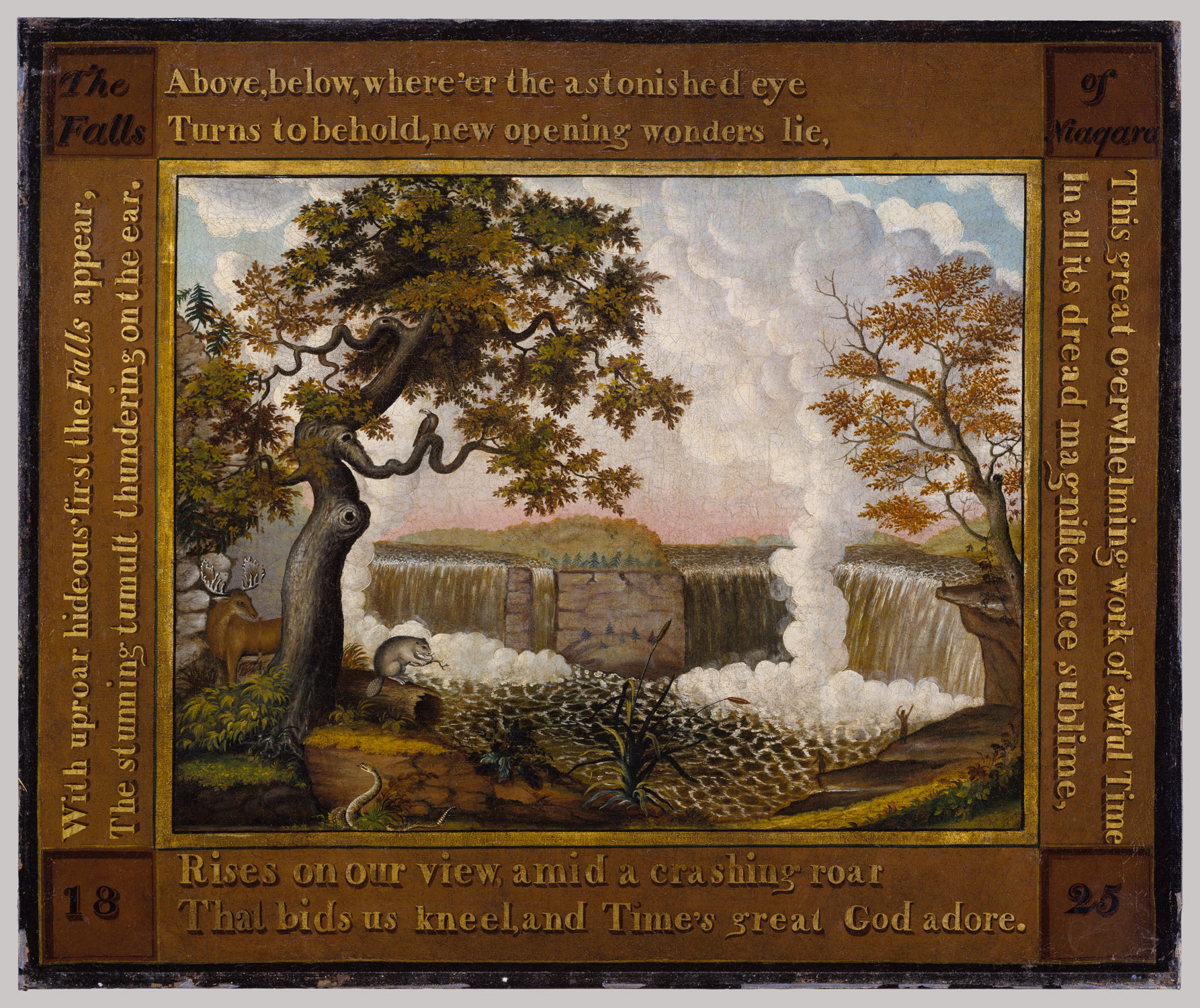

The Falls of Niagara, ca. 1825

Edward Hicks (American, 1780–1849)

Oil on canvas; 31 1/2 x 38 in. (80 x 96.5 cm)

Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1962 (62.256.3)

Hicks's 1825 painting of The Falls of Niagara shows the cataract from the Canadian side, along with the moose, beaver, rattlesnake, and eagle that have traditionally been used as emblems of North America. Inscribed around the border is an excerpt from Alexander Wilson's poem, "The Foresters." The painting, a sort of visual sermon, can be interpreted as a commemoration of Hicks's missionary work among Native American tribes in upstate New York.

Joshua Johnson (active ca. 1796-1824), Edward and Sarah Rutter, ca. 1805, Oil on canvas, 36 x 32 in. (91.4 x 81.3 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1965 (65.254.3)

Joshua Johnson (active 1796-1824) is the earliest African-American painter in the United States with a recognized body of work. Johnson (whose name is sometimes spelled Johnston) was brought to Baltimore in the 1790s as a slave for a family that was related to Charles Willson Peale, the celebrated portrait painter. Within a decade Johnson became a "freeman of color" and was earning his living as a portrait painter. Although early works show Peale's influence, Johnson soon developed a more personal and less academic style, in which facial features were idealized, while details such as fine lace overlaying another fabric received a very literal treatment. Johnson's affinity for bright, strong colors and precise details can be seen in the portrait of Edward and Sarah Rutter, whose air of stillness gives it an unreal, almost magical feeling.

Mrs. Mayer and Daughter, 1835–40

Ammi Phillips (American, 1788–1865)

Oil on canvas; 37 7/8 x 34 1/4 in. (96.2 x 87 cm)

Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1962 (62.256.2)

Ammi Phillips (1788-1865) was an itinerant portrait painter who settled in one community and then another along the Massachusetts-Connecticut border before moving on in search of commissions. In a career that spanned many years and underwent several stages of evolution and response to the influence of various artists, Phillips facilitated his work (by developing a formulaic approach to portraiture) at the same time that he personalized it (by imaginatively individualizing each one). The portrait of Mrs. Mayer and Daughter shows Phillips's combination of radically simple, elegant outlines with an assured coloristic refinement that borders on the urbane.

Works of art by nearly five dozen other named artists, as well as numerous pieces by unidentified makers, are also on view. Highlights include 27 scenes of city life by the tinsmith William P. Chappel (ca. 1800-1880), a work commemorating the first naval battle in the War of 1812 by Thomas Chambers (1808-after 1866), two religious paintings based on Biblical scenes and a portrait by Erastus Salisbury Field (1805-1900), a patriotic image of George Washington by Frederick Kemmelmeyer (ca. 1755-1821), and a watercolor portrait that was executed jointly by Ruth Whittler Shute (1803-?), who drew the likeness, and her husband Samuel Addison Shute (1803-1836), who painted it in.

Ambrose Andrews (ca. 1801-1877), The Children of Nathan Starr, 1835, Oil on canvas, 28 3/8 x 36 1/2 in. (72.1 x 92.7 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Partial Anonymous Gift, in memory of Nathan Comfort Starr (1896-1981), 1987 (1987.404)

John Bradley (active 1832-1847), Emma Homan, ca. 1844, Oil on canvas, 34 x 27 1/8 in. (86.4 x 68.9 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1966 (66.242.23);

Unidentified artist, Boy with Blond Hair, ca. 1840-50, Oil on canvas, 34 1/2 x 29 1/2 in. (87.6 x 75 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1973 (1973.323.5)

A Shared Legacy: FOLK ART IN AMERICA

Venues

American Folk Art Museum (New York, NY) December 13, 2014 - March 8, 2015

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO) March 28 - July 5

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art (Memphis, TN) November 7, 2015 - February 28, 2016

Westmoreland Museum of American Art (Greensburg, PA) July 10 2016 - October 2 2016

Denver Art Museum (Denver, CO) October 27, 2016 - January 22, 2017

Society of the Four Arts (Palm Beach, FL) February 11 2017 - March 30 2017

Cincinnati Art Museum (Cincinnati, OH) June 10 2017- September 3 2017

"A Shared Legacy: FOLK ART IN AMERICA" highlights art created by artists in rural areas in New England, the Midwest, and the South between 1800 and 1925 - artists who did not always adhere to the academic models that established artistic taste in urban centers of the East Coast. Included are portraits; vivid still life, landscape, and allegorical paintings; commercial and highly personal sculpture; and distinctice examples of furniture from the German-American community. More than 60 works, including paintings on canvas, panel, and paper by some of the most admired 19th-century American painters; sculpture; and examples of American furniture and other household objects, exemplify the breadth of American creative expression during a period of enormous political, social, and cultural change in the United States.

Rooted in the family as well as the preservation of personal and cultural identity, art was one means by which Americans living far from their places of origin maintained a bond to the lives they had known. As communities were established and became prosperous, many people sought tangible evidence of their success. In Eastern cities, the well-to-do patronized trained artists who had studied at home or abroad. However, to meet the demand of customers who were living far from urban centers, self-taught or minimally-trained artists arose to create art for customers or for their own pleasure. A need for art in outlying areas fostered the emergence of several generations of artists who were responsible for a pivotal development in the history of American art.

"Ammi Phillips, James Mairs Salisbury, oil on canvas, c. 1840"

"Daniel McDowell, Still Life with Watermelons, c.1860, oil on canvas"

"Edward Hicks, The Peaceable Kingdom with the Leopard of Serenity, oil on canvas, 1846-48"

.jpg/451px-Edvard_Munch_-_Madonna_-_Google_Art_Project_(495100).jpg)