ALBERTINA

8 February – 19 June 2022

The ALBERTINA is dedicating its major spring exhibition of 2022 to Edvard Munch (1863– 1944). This comprehensive showing is unique in several respects: more than 60 works by the Norwegian artist exemplify his impressive oeuvre as one that has been groundbreaking for both modern and contemporary art. Edvard Munch. In Dialogue focuses primarily on Munch's later works and their relevance to contemporary art. Alongside iconic versions of the Madonna and the Sick Child as well as Puberty, it is ultimately also a number of landscape paintings—bearing witness to the uncanny, the threatening, and the alienating—that place Edvard Munch’s perspective on nature, that central theme of symbolism and expressionism, in dialogue with groups of works by important artists of our own time.

In addition to the direct variations on Munch's iconic images, the exhibition will focus on works by artists who are linked to Munch's experimental and modernist expansion of the concept of painting. Munch’s reception among protagonists of contemporary art is attested to by seven important artists of the present—all of them 20th-century greats—who enter into dialogue with him: Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Georg Baselitz, Miriam Cahn, Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas, and Tracy Emin. The selected groups of works by these artists impressively illustrate the influence that Munch’s art continues to have on subsequent generations.

Andy Warhol

The American Andy Warhol works on Munch's most famous prints: The Scream, Madonna and Munch's Self-Portrait with Bone Arm. Warhol adapted these motifs and created variations in the style of Pop Art. While he makes hardly any changes to the original composition and the subjects of the depiction, Warhol relies above all on the use of various garish colour combinations to create different variations. In this way, he succeeds in rediscovering Munch's prints again and again, modifying them and ultimately transforming them into his own works of differentiated expressiveness.

Jasper Johns

Conversely, the American artist Jasper Johns discovered an alienating pattern in one of Munch’s late works—Self-Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed—that he then proceeded to isolate and use to cover one of his own paintings as an all-over texture. The abstractornamental pictorial element of a bedspread in a late, pessimistic, midnight self-portrait by Munch becomes Johns' almost obsessively pursued source of inspiration.

Georg Baselitz

Baselitz's reception of Munch includes his forest landscapes and his portraits of the Norwegian painter, some of which are indirect. The German artist sees in the Norwegian the painter who doubts himself and recognises in his nocturnal solitude his artistic destiny. He is fascinated by the everydayness of Munch's portrayals, their dreariness, but also by the inner tension and restlessness that his works trigger, as well as their fleetingness and fragmentary nature.

Miriam Cahn

The works by Miriam Cahn likewise revolve around human emotions ranging from powerless despair and fear to unbridled aggression. That which, in Munch’s output, refers to the battle between the sexes in a way that is typical of his era is turned by Miriam Cahn into an open statement concerning the oppression of women in which her works’ uncanny atmosphere indeed seems derived from Munch’s uncanny experience of nature. While Edvard Munch took the threatening of man by woman, by the femme fatale, as the central theme in his series The Frieze of Life, Marlene Dumas reinterprets this iconography in images that portray the colonial and racist oppression of Africa’s black population. At the same time, her fascination with the Norwegian artist’s love of coloristic experimentation equals that of Peter Doig.

Marlene Dumas

Marlene Dumas takes a deep dive into fundamental questions of human experience, placing themes such as love, identity, death, and mourning at the center of her work, thereby effecting a direct continuation of Munch’s substantive emphases. For the South African artist Marlene Dumas, Munch's pessimistic view of the world is not only the basis for individual fate, but a symbol for the oppression of mankind itself, for the conflict between man and woman, between blacks and whites. With her existential themes, Dumas' content connects very directly with Munch's emotionally charged depictions.

Tracey Emin

Tracey Emin’s paintings and multimedia works, on the other hand, are characterized by traumatic personal experiences and take up the autobiographical character of Munch’s output. Like Munch, the Englishwoman expresses a strong personal component in her artmaking. For her, Edvard Munch is the exemplary artist par excellence who has given expression to the psychological decay of modern man. 5

Peter Doig

Peter Doig also views the materiality of Munch’s paintings, along with the iconography of human beings’ alienation from themselves, as an important point of reference in the Norwegian artists oeuvre. Following Munch's epochal pictorial worlds, he explores the question of the location of the individual in the modern world. Alongside pessimism and the growing theme of being alone in the world, it is Munch's love of experimentation that interests painters like Peter Doig in the Norwegian's work.

This presentation picks up where the ALBERTINA Museum’s record-breaking Munch exhibitions of 2003 and 2015 left off and is being supported by the Munch Museet in Oslo as well as by numerous other international institutions and private collections. The works were selected together with the living artists.

Images

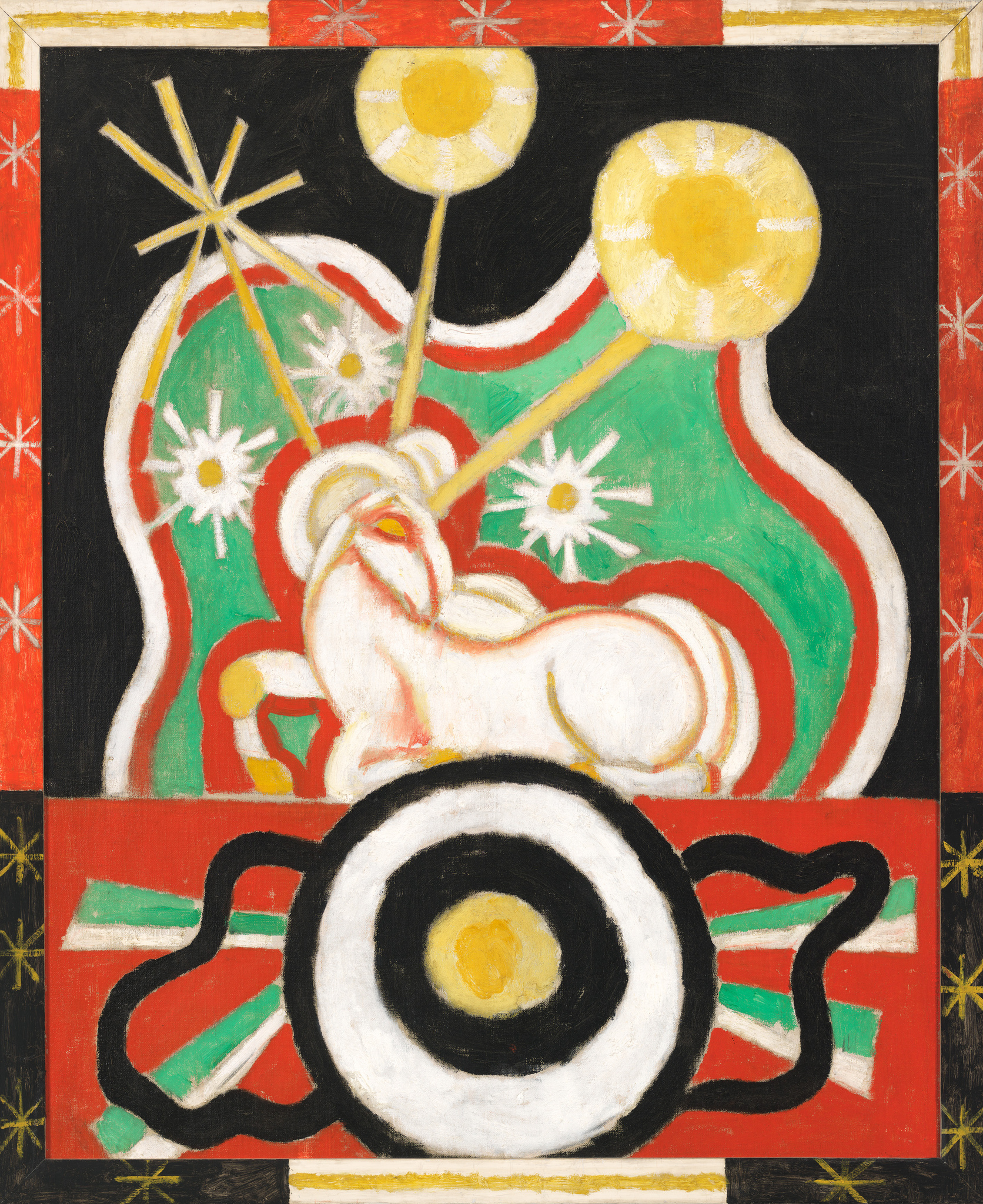

![]()

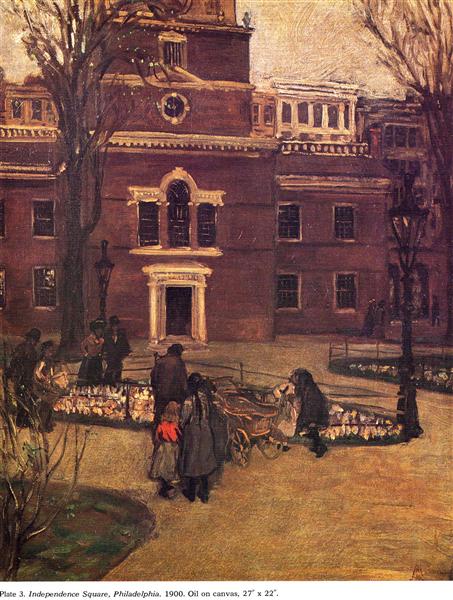

Edvard Munch

Street in Aagsgaardstrand, 1901

Oil on canvas

Kunstmuseum Basel, gift of Sigrid Schwarz von Spreckelsen and Sigrid Katharina Schwarz, 1979 © Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P.Bühler

Photo: Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler

![]()

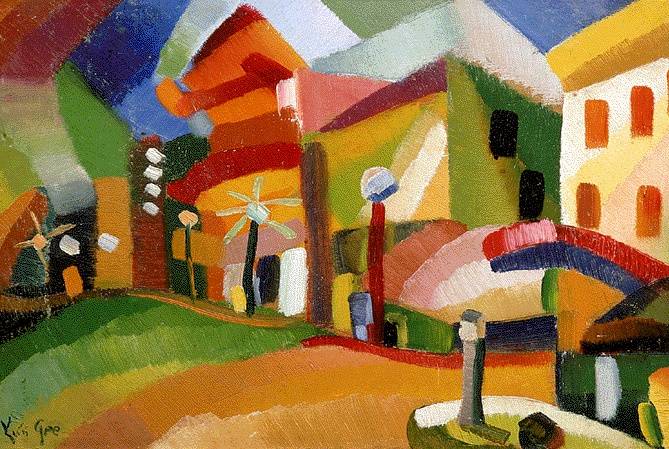

Edvard Munch

The Kiss, 1921

Oil on vancas

© Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, Houston

![]()

Andy Warhol

The Scream (after Munch), 1984

Silkscreen on Lenox Museum Board

Mikkel Dobloug, Kjell S. Stenmarch, Grev Wedels Plass Auksjoner © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Bildrecht, Vienna 2022

![]()

Andy Warhol

Madonna and Self-Portrait with Skeleton’s Arm (After Munch), 1984

Silkscreen on Lenox Museum Board

Gunn and Widar Salbuvik © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Bildrecht, Vienna 2022 © Michal Tomaszewicz

![]()

Edvard Munch

Madonna, 1895/1902

Color lithograph with lithographic chalk, ink and needle in black, olive, blue and red / Japanese paper

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna © The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

![]()

Edvard Munch

Self-portrait (with bone arm), 1895

Lithograph with lithographic chalk, ink and needle in black

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna © The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

![]()

Edvard Munch

Winter Landscape, 1915

Oil on canvas

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna – The Batliner Collection © The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

![]()

Georg Baselitz

Ekely, 2004

Oil on canvas

Private collection Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac, London - Paris - Salzburg - Seoul

Photo: Jochen Littkemann © Georg Baselitz

![]()

Edvard Munch

The sick child, 1907

Oil on canvas

Tate: Tate: Presented by Thomas Olsen 1939 © Tate

![]()

Jasper Johns

Corpse and Mirror, 1976

Silkscreen

Collection of Catherine Woodard and Nelson Blitz, Jr. Foto: Bonnie H. Morrison © Jasper Johns / Bildrecht, Wien 2022

![]()

Jasper Johns

Savarin, 1977-1981

Color lithograph

Collection of Catherine Woodard and Nelson Blitz, Jr. Foto: Bonnie H. Morrison © Jasper Johns / Bildrecht, Wien 2022

![]()

Tracey Emin

Sometimes There Is No Reason, 2018

Acrylic on canvas

Private Collection, Courtesy Sabsay © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022 © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved / Bildrecht, Vienna 2022

![]()

Tracey Emin

You Kept It Coming, 2019

Acrylic on canvas

Private Collection © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022 © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved / Bildrecht, Vienna 2022

![]()

Marlene Dumas

Evil is Banal, 1984

Oil on canvas

Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven © Peter Cox, Eindhoven © Marlene Dumas

![]()

Marlene Dumas

Nuclear Family, 2013

Oil on canvas

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel © Peter Cox, Eindhoven © Marlene Dumas

![]()

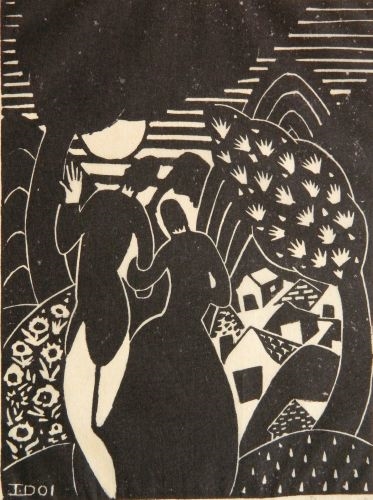

Miriam Cahn

HANDS UP!, 2014

Oil on canvas

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Jocelyn Wolff © Serge Hasenboehler

![]()

Miriam Cahn

madonna (bl.arb.), 1997

Oil on canvas

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Jocelyn Wolff © Francois Doury

![]()

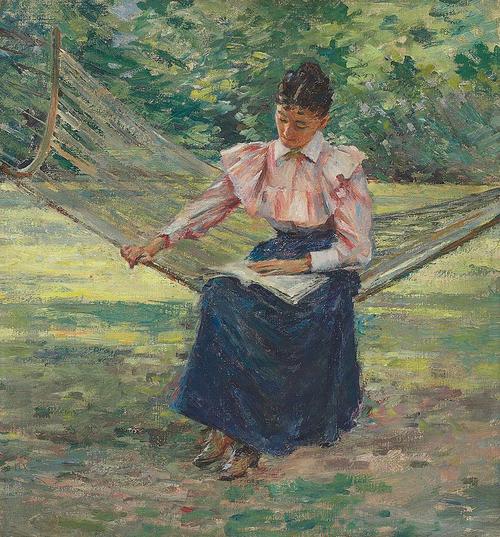

Peter Doig

Echo Lake, 1998

Oil on canvas

Tate: Presented by the Trustees in honour of Sir Dennis and Lady Stevenson (later Lord and Lady Stevenson of Coddenham), to mark his period as Chairman 1989-98, 1998 © Tate

![]()

Tracey Emin

This Was The Beginning, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

© Tracey Emin, All rights reserved / Bildrecht, Vienna 2021

![]()

Georg Baselitz

Forest Landscape, 1974

Oil on canvas

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna – The ESSL Collection © Georg Baselitz

![]()

Georg Baselitz

Painter with mitten, 1982

Oil on canvas

Albertinum | Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden State Art Collections, Foundation G. and A. Gercken

© Photo: Albertinum | Galerie Neue Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut

![]()

Edvard Munch

Madonna, 1895-96

Oil on canvas

Collection of Catherine Woodard and Nelson Blitz, Jr.

Photo: Bonnie H. Morrison

![]()

Edvard Munch

The Nightwalker, 1923-1924

Oil on canvas

Munchmuseet

Photo: Munchmuseet/Ove Kvavik

![]()

Edvard Munch

Women in the Bath, 1917

Oil on canvas

Munchmuseet

Photo: Munchmuseet/Ove Kvavik

![]()

Edvard Munch

Puberty, 1914-1916

Oil on canvas

Munchmuseet

Photo: Munchmuseet/Halvor Bjørngård

![]()

Georg Baselitz

Edvard's Ghost, 1983

Oil on canvas

Private property

Photo: Jochen Littkemann

Exhibition Texts

Edvard Munch

Early Years

In the early 1880s, Munch studied painting at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania, today’s Oslo. Initially, his paintings were still influenced by the naturalism of his colleagues and mentors Frits Thaulow and Christian Krohg, his seniors by several years, but Munch would soon turn away from their style. During those years, he also frequented Kristiania’s Bohemian circle of artists and poets, headed by the writer and anarchist Hans Jæger, who rejected a bourgeois life and any form of nationalism, designing the utopia of a liberated social life in his prohibited programmatic pamphlet. Jæger’s theories impacted not only on Munch’s art, but also on his writings, which the artist penned alongside his activities as a painter.

When presented publicly for the first time at Kristiania’s 1884 autumn salon, Munch’s paintings met with criticism. And when he exhibited another four works at this show only two years later, he caused a genuine scandal with the first version of The Sick Child, then entitled Study, in which the painter dealt with the premature death of his sister Sophie, who had succumbed to tuberculosis. The reason for the outrage was Munch’s unconventional style, his abandonment of the traditional academic notion of painting. Critics referred to the depiction as a “mess of smearing.”

Around 1890, Munch conceived his first Symbolist works. In his impressive landscape compositions nature becomes a projection screen for human emotion, a mirror of the soul. Particularly Åsgårdstrand on the coast of the Oslofjord, where Munch rented a house over the summer month, would become a special place of inspiration for him. Munch primarily came into touch with Symbolism during his stays in Paris, where he familiarized himself with the art of the contemporary avant-garde. The painting of Vincent van Gogh, Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec eventually also influenced his work.

First Successes

In 1892, Munch’s pictures were presented in an exhibition at the Berlin Artists’ Society, which brought about a scandal. Again, his style was harshly criticized. The remaining artists jointly decided to close the show prematurely, which, however, only contributed to Munch’s becoming known even better. The Norwegian moved to Berlin, where he joined the intellectual literary circle at the “Black Piglet” tavern. Among its members were August Strindberg, the writers and critics Stanisław Przybyszewski and Julius Meier-Graefe, as well as Przybyszewski’s future wife, Dagny Juel. It was probably during that time that Munch began exposing his paintings to the elements in what was a drastic “kill-or-cure” procedure. Munch’s individual artistic approach linked him to diverse groups of the international avant-garde.

In 1906, his works were on view at the groundbreaking exhibition of the Fauves at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris; in 1908, the Norwegian took part in a show of the Brücke group of artists in Dresden and became an artistic role model for Expressionist painters in Germany. Since the turn of the century, Munch had had to struggle with psychological problems and alcoholism and therefore repeatedly stayed at various clinics. In 1908 he entrusted himself to the care of the Danish psychiatrist Daniel Jacobson, who treated him successfully at his sanatorium near Copenhagen. His failed relationship to Tulla Larsen had partly been responsible for the deterioration of his mental condition. Following numerous quarrels, they separated after a dramatic and fateful fight. In some sort of scuffle, a shot from a weapon was released, and Munch was wounded in his left hand, losing the upper phalanx of his middle finger.

Munch’s relationship to the female sex would remain ambivalent for the rest of his life. This is also reflected in many of his works in which he addresses the complexity of the liaison between man and woman, which for him inevitably went hand in hand with hurt and emotional pain.

Later Years

Edvard Munch became more and more successful. Solo exhibitions in Zurich, Bern, and Basel in 1922, invitations to group exhibitions and as a guest of honor to Gothenburg, as well as his appointments as member of the Prussian Art Academy and honorary member of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts in 1923 attest to his growing recognition. He traveled widely across Europe. Prestigious commissions to paint murals, as well as numerous international retrospectives indicate his position as foremost exponent of modern art. In 1926 his sister Laura died, who had suffered from depression for many years. In 1930 the rupture of a blood vessel in Munch’s right eye nearly caused blindness albeit temporarily. Munch journalized the progress of his ailment with almost scientific accuracy, producing a number of drawings and watercolors. Photographic self-portraits also date from this period, all of them close-up views; at the same time, he once again painted a large number of selfportraits. The death of his aunt Karen Bjølstad the following year led to his in-depth exploration of the subjects of old age and death. Starting in the mid-1930s, he created compositions of intense brilliance.

A man’s longing for a woman continued to be represented as unfulfilled utopia for Munch even in his late work. The free, open, and loose brushwork actually lets themes that used to torment the artist appear somewhat lighter, as if Munch had exchanged the protagonist’s role for that of an observer. Munch lived a secluded life, “entirely like a hermit,” as he himself described it, with his eye condition limiting him in his work. In 1937 he took part in numerous exhibitions, including the Paris World’s Fair; that same year, his works were confiscated as “degenerate” from German museums and private collections. When offered a large-scale exhibition in Paris in 1939, he declined.

From 1940 on, Munch worked on his last self-portraits, marked by a profound analysis of the theme of death. He said: “I don’t want to die suddenly. I would like to have this final experience.” Munch lived an isolated life at Ekely, growing his own fruit and vegetables and avoiding contact with the Germans occupying the country. Shortly after the celebrations of his 80th birthday, Munch contracted pneumonia and died peacefully at Ekely soon afterwards.

Miriam Cahn

Born 1949 in Basel The focus of Swiss artist Miriam Cahn’s oeuvre is on present-day socio-political themes, above all feminism’s questioning rigid gender roles. In her works she seeks to shock and direct attention to social deficits. War, expulsion, and escape, the defense of human rights, the liberation from suppression, and the rejection of a male construct of power push to the fore. Her female figures always vigorously resist persecution or male aggression and control. What Miriam Cahn’s art shares with that of Edvard Munch is above all the depiction of extreme emotions. Emotional outbursts of fear, rage, and anger are essential catalysts in her pictures. Like Munch, Cahn attempts to express humankind’s existential misery. Similar to Munch, she considers this misery rooted in the battle of the sexes: whereas Munch, as was typical of his age, saw the reason for despair in the woman and her instincts and passions, Miriam Cahn associates humankind’s desolation with male predominance. Adapting Edvard Munch’s chromatically ominous moods, Miriam Cahn uses toxic, iridescent colors, which she combines with a sallow and gloomy basic tone. Cahn’s protagonists move about in empty, undefined spaces while conveying feelings of being lost, isolated, and secluded. The artist mostly presents her anonymous figures in the nude and without hair. They powerfully communicate via their facial features and gestures, similar to the sexless being in Munch’s The Scream, whose terrified expression and wide-open mouth suggest existential loneliness.

Peter Doig

Born 1959 in Edinburgh An essential ambition of Peter Doig’s painting is to express human emotion in view of overwhelming nature: a theme that also preoccupied Edvard Munch. Nature becomes a vehicle of such feelings as loneliness and human forlornness. In Munch’s art, this view of the world culminated in his iconic work The Scream. In Doig’s work, this terrifying insight has eventually taken shape in such central works as Echo Lake, which stimulates questions about human existence. With his meditative landscapes, the artist felicitously captures the sound of silence in a painterly manner. At the same time, they convey the impression of profound melancholy, a sense of emptiness and isolation that goes hand in hand with emotional numbness and alienation. Doig mostly presents human beings as lost individuals, with nature becoming a metaphor for their lonesomeness. Doig’s vast, scantily populated sceneries, mysterious forests, or endless waters are inhabited by an uncanny element that relates them to Munch’s understanding of nature.

Tracey Emin

Born 1963 in London Tracy Ermin’s output is characterized by an unsparing analysis of her innermost feelings and their candid exposure to the outside world. In this respect, her oeuvre, which is strongly informed by her autobiography, reveals immediate parallels to that of Edvard Munch, who digested painful personal experiences in his pictures, including melancholy, fear, illness, death, and loss. As far as this uncompromising introspection is concerned, the Norwegian is an important artistic example for Tracey Emin. Emin’s works similarly draw their strength from her dealing with her own vulnerability, with the fragility of human existence. The unembellished reproduction of harsh reality is a thread running through Emin’s entire oeuvre. By addressing such themes as abortion, miscarriage, alcoholism, and—both physical and psychological—violence, the artist negotiates experiences from her own life. Due to this unvarnished exposure of emotional 11 vulnerability she achieves an unusual sensitivity in her pictures, which touches the viewer profoundly and with great immediacy while reflecting the self-analysis also inherent in the work of Munch. What connects these two artists are the psychological depth of their works, their soulsearching, and the exposure of their inner lives. In Tracey Emin’s own words, every single painting by her on view here represents the art and worldview of her Norwegian role model.

Georg Baselitz

Born 1938 in Deutschbaselitz Fascinated by the tristesse in Munch’s works, by the inner tension and restlessness they convey, and by their fleeting and fragmentary nature, Georg Baselitz has been profoundly impressed by the oeuvre of his Norwegian role model as a painter from the 1980s onward. Baselitz is not interested in harmony but rather goes in search of the dissonance encountered in Munch’s art. Like Munch, who then caused a sensation with his innovative approaches, Baselitz similarly seeks to free painting from conventions. Turning his motifs upside down, which boils down to a destruction of conventional pictorial concepts, has become his signature feature. Formally, Baselitz’s expressive brushwork and radically cropped views link his works to those of Munch. Baselitz makes reference to both Munch’s figural depictions and landscape elements, thereby concentrating on the Norwegian’s central motif of sylvan solitude. In addition to painterly aspects, Baselitz is also interested in Munch’s thematic focal points. An essential factor is the psychological depth of Munch’s pictures, primarily the focus on the individual and his or her place in the world. It was above all in the 1980s that Baselitz dealt with Munch’s self-portraits, in which the painter presents himself as a lonely and abandoned figure. Baselitz’s portraits of Munch, in which the artist appears as “Edvard,” are less characterized by physiognomic resemblances but rather by formal and thematic references to Munch’s various self-portraits. In his series of the cut-off feet, Baselitz directly harks back to a portrait photograph of the ageing Munch at Ekely, choosing an unconventional approach to portraiture by making the feet the 12 artist’s deputy. Georg Baselitz’s first “Munch portraits” are the most stunning documents of self-doubt and deep loneliness the German artist painted in the 1980s, when he was already successful. They revise the image of a prince of painters imposed upon Baselitz by others. He only felt understood by Edvard Munch, in whom he saw himself.

Marlene Dumas

Born 1953 in Cape Town Marlene Dumas’s oeuvre deals with profoundly existential questions of ethnic origin, apartheid, gender, and human destiny. In this, Dumas’s art corresponds with Edvard Munch’s emotionally charged representations: fundamental themes of your existence, such as love and sensuality, anxiety and death, the problem of identity, and the complexity of interpersonal relationships are not only the pillars of Dumas’s artistic activity but also significant elements in the work of Edvard Munch. In her pictures, Dumas draws many parallels to Munch, whom she discovered for her own art at the Munchmuseet in Oslo in the 1980s. Dumas was also fascinated by Munch’s love of painterly experiment, a feature constituting the foundation of his modernity. The habit of subtracting paint, of leaving compositions unfinished, the play with contrasting forms of color and vacant passages on the canvas in combination with a diaphanous brushwork are features shared by the two artists. Munch’s way of expanding the pictorial content by a work’s title is also a characteristic reflected in Dumas’s artistic practice time and again. Both Munch and Dumas thus do not simply depict in their works what can be seen, but they create a deeper, symbolist level.

Edvard Munch Prints

Apart from his painted work, Edvard Munch has left behind an equally important printed oeuvre, with series and variations playing a central role. The interplay between painting and printmaking and their cross-fertilization proved essential for Munch’s creative process. In terms of motif, the Norwegian artist regularly revisited themes in his printmaking he also negotiated in his painting. The painted version did not always come first—sometimes the printed version constituted the starting point. The artist partly dealt with the same subject matter over decades, tackling it with ever-new ideas and vigorous creativity. While Munch’s initial embrace of printmaking was commercially motivated—what mattered was first and foremost a fast, uncomplicated, and inexpensive dissemination of his works— by 1896 at the latest, during his stay in Paris, which was then the center of avant-garde printmaking, the artist had also discovered the medium as an artistic challenge.

He experimented with various techniques, from woodcut and lithography to etching and drypoint. In his woodcuts, Munch deliberately incorporated the visible vertical grain of the woodblock into his pictorial compositions, playing with form and materiality. The artist frequently sawed panels apart to achieve new coloring possibilities. Through subsequent individual interventions or the use of special papers, numerous unique impressions were created. Munch detected new forms of artistic expression offered by the paper and the woodblock or plate, comparable to the incorporation of the untreated canvas in his paintings. Furthermore, Munch experimented with edge-to-edge prints that ignored the margins of the pictorial support.

Due to these innovative approaches, Munch, together with Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, and Francisco de Goya, doubtlessly ranks among the big names in art history whose printed oeuvres and painted works were equally significant. The hierarchy of the media was thus annulled.

Andy Warhol

Pittsburgh 1928 –1987 New York

In the early 1980s, Andy Warhol, probably the most famous exponent of US-American Pop, took to dealing intensively with the work of Edvard Munch. In this context, a visit to a Munch exhibition at Gallery Bellman in New York played an important role, where Warhol purchased four original prints by the Norwegian: the outstanding works The Scream, Madonna, Self-Portrait with Skeleton’s Arm, and The Brooch. Eva Mudocci. Adapting these motifs, Warhol created variations of them in the style of Pop. While leaving the original composition and depiction practically unchanged, Warhol made use of various garish color combinations to arrive at several variants. He thus successfully rediscovered Munch’s prints time after time by modifying them, eventually arriving at his own works, with their individual and nuanced expression. Munch too had revisited certain pictorial themes so as to be able to vary them in his paintings and prints, tackling them anew with innovative ideas. However, it is above all the function of the universally recognizable icon that plays a crucial role in Warhol’s reception of Munch’s art. In his portraits of such Hollywood celebrities as Marilyn Monroe and Liz Taylor, Warhol dealt with the idolization of prominent personalities that had become emblems of entire generations—which was then critically questioned by the artist, as he did with icons of art history.

After Warhol’s treating them in his serial processes, famous works of art from the Renaissance to modernism, including examples by Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, or Pablo Picasso, emerged as his own variations. The After Munch series also belongs to this group, as Munch’s works, first of all The Scream, had evolved into icons of art history. Warhol’s dealing with this very motif, the embodiment of the isolated individual, goes back to his own exploration of such central aspects of human existence as fear, death, and transience.

The Scream

There is no work of art in which existential fear, man’s primal fear, has been captured more impressively than in The Scream, Edvard Munch’s most famous masterpiece: a sexless being with a terrified expression staggers along a bridge that pulls into the picture’s depth. Munch was not guided by an interest in rendering what he saw true to life; rather, the artist sought to give expression to his innermost feelings, thus rejecting such styles and movements as naturalism and Impressionism, as well as the traditional definition of art as mimicry of nature. Munch’s simplification of motifs, the figure’s iconic frontality, the extreme perspective, and the unusual rendering of the landscape, which seems to liquefy within a maelstrom of lines, are highly radical.

An experience Munch had had during a walk at the Oslofjord in 1892 originally motivated him to capture the agitation of the soul visually. In a diary entry, the artist noted down: “I was walking along the road with two friends—the sun was setting—and I felt a wave of sadness. Suddenly, the sky turned bloodred—I paused—leaning against a fence tired to death—above the blue-black fjord and city blood and flaming tongues hovered—my friends walked on—I stayed behind quaking with angst—and I felt the great scream in nature.”

The figure in The Scream has become a symbol of the individual who gets lost in the big whole. Munch’s depiction is an expression of society’s fear at the dawn of modernism. This aestheticism of fear has been continued in the work of numerous present-day artists, one of the most important ones being Andy Warhol, with his adaptation of Munch’s The Scream. Similarly, he harked back to the scenarios of horror in Munch’s oeuvre with the Car Crash series, the Electric Chairs, and the Suicide pictures. His versions of The Scream in garish fluorescent colors seem to have sprung from a psychedelic nightmare. In the course of his immersion in Munch’s iconic work, Warhol stated: “I realized that everything I do has something to do with death.”

Jasper Johns

Born 1930 in Augusta, Georgia

Like Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, whose work is as close to Pop art as it is to Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Dada, has repeatedly made reference to Edvard Munch, by whose paintings he was already impressed when attending the artist’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1950. In the decades to come, he was to revisit the latter’s pictures time and again, choosing a new and highly individual approach to Munch’s oeuvre that mainly had to do with an adoption of motifs in combination with tendencies toward abstraction. Creating non-figurative variations of Munch’s pictures, Johns has created characteristic reinterpretations in which he seeks to connect up to the Norwegian’s central topics, devoting himself to such themes as love and sexuality, death and loss.

An important point of departure for Johns is Munch’s final self-portrait Between the Clock and the Bed, which deals with the transience of human existence, the opposites of life and death, the aspect of time, and the natural cycle of an individual’s life from birth to deathbed. A central element is the pattern of crosshatching, which Johns resorts to in order to create his own abstract versions of the subject while recontextualizing it in the manner of a geometric composition.

By reducing the motif to non-representational geometry and translating Munch’s figural subject matter into abstraction, Johns has succeeded in creating a highly individual and innovative approach to the reception of Munch’s art.

Edvard Munch, Madonna, 1895/96

In only three years, from 1893 on, Munch executed five painted versions of the subject of the Madonna, also referred to as Loving Woman or Conception, in addition to numerous color lithographs. The third version of this three-quarter-length nude in the controversial guise of a femme fragile or femme fatale ecstatically bent backward stands out for its unusual technique. In its compact form, the oil paint has only been used partially for the black hair, red aureole behind the head, mouth, and eyes; the experimental use of thinly applied spray paint for the flesh and the bluish green and reddish aura around the figure dominates. Munch dissolved small amounts of pigment in turpentine, adding some glossy varnish.

The work’s sketchy appeal results from the preliminary drawing in colored chalk that has remained visible and which has only been partially reinforced with brushstrokes. Such oil paintings were criticized as raw and unfinished at the time.

Edvard Munch, Puberty, 1914-16

Besides The Sick Child and The Day After, Puberty is thought to mark Munch’s embrace of modernism. The first version of 1886 fell victim to a fire, and following the version owned by the National Gallery in Oslo from 1894, encircling important motifs within a series proved a forward-looking aspect. In his version from 1914–16, the artist has accentuated the emotionally charged situation of an adolescent becoming aware of her femininity through the pose, gesture, view from above, and looming shadow on the wall, augmenting the effect through contrasts of color and light and dark, wild paintbrush dabs, and rapidly applied open strokes. This painterly vehemence is still apt to convey the artist’s nervous mentality. Around 1900, his thematic candidness equaled the exposure of restrictive sexual morals, which initially led to the closure of his exhibitions in Norway and Germany.

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1907

This is the fourth version of the subject first explored in 1885/86: a painterly paraphrase determined by contrasts of red and green. Munch would create two more oil paintings as well as graphic versions of the motif until 1926. Purchased in 1928 by Hans Posse for the Dresden Gemäldegalerie, the painting was confiscated in 1937 as “degenerate” and sold through art dealers to Norway and later to the Tate Gallery. Munch had accentuated even the first version of the painting commemorating his dead sister Sophie with numerous incisions and described it as “perhaps my most important picture.” The sick girl’s expression has changed in this version of the favored motif. She directs her more hopeful gaze toward the window in vibrant restlessness. The left hand of the mother, whose grief Munch emphasizes particularly in this version, seems to approach the girl’s right hand. The restless brushwork on the left, on the pillow, and in the hair contrasts with the vertical stripes and the black on the right, which—as intended by the artist—strongly charges the gestures and postures with emotion.

Edvard Munch, Women in the Bath, 1917

Munch was preoccupied with photography time and again and, having bought his first camera in 1902, began experimenting with it, probably also inspired by August Strindberg, whom he had met in 1892. Munch was mainly interested in the spookiness of double exposure, blurred motion, and development errors. In his paintings and prints, he seeks to make the “uncertain” outcome of the work process visible. Much later, such photographic models led to his attempts at overlapping two compositions with both linear and painterly means in Women in the Bath. The group of bathers in the background seems to be a copied painting. In front of it we can see a female nude or, as a variant, a naked woman and child seated on blankets. A third layer in the form of sketched portraits and further nudes has then been superimposed on these two levels of reality in a way reminiscent of double exposure. The result is marked by a mysterious and visionary transparence and a break with the dimension of time.

Edvard Munch, Self Portrait with Spanish Flu, 1919

In 1918/19 Munch contracted the Spanish flu, a global pandemic. Despite the weak condition of his lungs, which he had inherited, he overcame the crisis. In both versions of his selfportrait—the one from the National Gallery in Oslo and the one from Lübeck’s Museum Behnhaus Drägerhaus—the artist gives the impression of an aged man although he was only fifty-six years old. Nevertheless the full-length portrait in profile showing the convalescent in a wicker chair at his house at Ekely conveys a more positive atmosphere. Instead of a skull-like face, here it is only the tired eyes and the somewhat sunken, yet already eager posture dampening the vivid expression achieved through sweeping brushstrokes and colorful contrasts—a manner of painting typical of his late period, in the years following his return home.

Edvard Munch, The Kiss, 1921

Munch had already set the motif of the kiss against a coastal landscape in his frieze for the Lübeck ophthalmologist Max Linde around 1914. In 1921, he repeated the couple merging with the branches of a tree with their faces flowing into each other. The use of reddishbrown and green diluted with turpentine in the horizontal coastal strip, strong outlines, and the phallic yellow moon pillar in the blue make this version richer in contrast. The woman’s light blue clothing distances her from the man’s dark suit. The night has lost its menace compared to early works, while the harmonious connection of man with nature has increased.

Edvard Munch, The Night Wanderer, 1923/24

As with Rembrandt, self-reflective portraits accumulate in Munch’s late work. A frequent insomniac, Munch clearly depicts his nervous constitution in his unstable posture next to a piano and in front of windows including the midnight blue throwing a gloom over the scene. Night and premonition of death belonged together for the artist from the beginning, and the musical instrument harks back to the traditional vanitas mood of art history. Regardless 20 of the shadowing of the face, especially the eyes, the dressing gown and the incidence of light and color contrast suggesting moonlight have something comfortingly ironic, which corresponds to the artist’s consistent processing of his traumatic emotions in painting.

Georg Baselitz, Painter with Mitten, 1982

With his work Painter with Mitten, Georg Baselitz makes direct reference to Munch’s self portrait The Sleepwalker, in which tension is created by the way the figure overlaps with the left margin of the picture, whereas the painter in Baselitz’s depiction, due to the reversal of the motif, is framed by the right margin, with the canvas as such becoming the pictorial space. It is not only the way in which the figure is bent forward that Baselitz’s painter and Munch’s somnambulist have in common; the two works also share the dark eyeholes and the corners of the mouth pointing downward—or actually upward in the case of Baselitz, as the composition has been turned upside down. It seems that apart from The Sleepwalker, Painter with Mitten has also been inspired by other examples of Munch’s numerous selfportraits.

Miriam Cahn

Born 1949 in Basel The focus of Swiss artist Miriam Cahn’s oeuvre is on present-day socio-political themes, above all feminism’s questioning rigid gender roles. In her works she seeks to shock and direct attention to social deficits. War, expulsion, and escape, the defense of human rights, the liberation from suppression, and the rejection of a male construct of power push to the fore. Her female figures always vigorously resist persecution or male aggression and control. What Miriam Cahn’s art shares with that of Edvard Munch is above all the depiction of extreme emotions. Emotional outbursts of fear, rage, and anger are essential catalysts in her pictures. Like Munch, Cahn attempts to express humankind’s existential misery. Similar to Munch, she considers this misery rooted in the battle of the sexes: whereas Munch, as 21 was typical of his age, saw the reason for despair in the woman and her instincts and passions, Miriam Cahn associates humankind’s desolation with male predominance.

Adapting Edvard Munch’s chromatically ominous moods, Miriam Cahn uses toxic, iridescent colors, which she combines with a sallow and gloomy basic tone. Cahn’s protagonists move about in empty, undefined spaces while conveying feelings of being lost, isolated, and secluded. The artist mostly presents her anonymous figures in the nude and without hair. They powerfully communicate via their facial features and gestures, similar to the sexless being in Munch’s The Scream, whose terrified expression and wide-open mouth suggest existential loneliness.

Peter Doig, Echo Lake, 1998

In his masterpiece Echo Lake, Doig directly refers to Munch and his work Ashes from 1895. The depiction of the landscape and the relationship between man and nature allow an immediate connection to be drawn between the two paintings. Munch’s composition is dominated by a woman dressed in white, who clasps her hands over her head in despair. In Echo Lake, Doig borrows this posture for the figure of the policeman. It is an expression of desperation and conveys feelings of fear and impotence. The thematic focus is once again on alienation. In both works we can also find the motif of mirror image, which for both Munch and Doig is of great significance as it is meant as reflection upon a person’s inner life.

Marlene Dumas, Evil is Banal, 1984

Like Munch, Dumas employs color as an explicit vehicle for the emotions that fill her pictures. Dumas’s faces from the 1980s stand out for their garish and frightening use of color. What is evil, ugly, menacing, or wounded in them haunts the viewers, forcing them to look away and then back again, as horrible sights often trigger voyeurism and fascination. Depicted are people from the street, whom Dumas met by chance and on whom she then focused her attention. The sick, jealous, fearful, and grieving people populating Munch’s works have found kindred spirits here.

Tracey Emin, Homage to Edvard Munch and All My Dead Children, 1998

Tracey Emin’s film Homage to Edvard Munch and All My Dead Children makes immediate reference to Edvard Munch’s iconic work The Scream. Shot on the shore of Åsgårdstrand, which provided not only the scenery for Munch’s key work but also for other central works of his, such as Angst or The Girls on the Bridge, the film focuses on such themes as alienation, emotional vulnerability, and the exploration of one’s innermost feelings. The artist presents herself crouching on a pier naked, in the position of an embryo, while emitting a powerful scream that impressively conveys sorrow and pain. Emin thus tried to work through her own traumatic experiences, above all abortion and miscarriage.

Emin, having translated the painted model of The Scream into her own, more realistic interpretation of the subject, and Munch share this disclosure of deeply personal experiences.

.jpg)