Van Gogh Museum

|

|

On the centenary of its status as the first public museum in the United States to purchase a painting by Vincent van Gogh, the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) presents a landmark exhibition that tells the story of the artist’s rise to prominence among American audiences. Van Gogh in America features paintings, drawings, and prints by the Dutch Post-Impressionist artist.

The exhibition’s presence in Detroit – and more generally, in the Midwest – holds special significance. The DIA’s 1922 purchase of Self-Portrait (1887) was the first by a public museum in the United States. Notably, the next four Van Gogh paintings purchased by American museums were all in the Midwest, where audiences were galvanized by Van Gogh’s rugged aesthetic, featuring subjects from modern, everyday life; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri; Saint Louis Art Museum; and Toledo Museum of Art. These important purchases – Olive Trees (1889; Kansas City);

Stairway at Auvers (1890; Saint Louis); Houses at Auvers (1890; Toledo); and Wheat Fields with Reaper, Auvers (1890, Toledo) – are all featured in the exhibition.

“One hundred years after the DIA made the bold decision to purchase a Van Gogh painting, we are honored to present Van Gogh in America,” said DIA Director Salvador Salort-Pons. “This unique exhibition includes numerous works that are rarely on public view in the United States, and tells the story – for the first time – of how Van Gogh took shape in the hearts and minds of Americans during the last century.”

One of the most influential artists in the Western canon, Van Gogh amassed a large body of work: more than 850 paintings and almost 1,300 works on paper. He began painting at the age of 27, and was prolific for the next 10 years until his death in 1890.

Works by Van Gogh appeared in more than 50 group shows before he finally received a solo exhibition in an American museum in 1935 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. Reflecting and fanning the excitement among American audiences for Van Gogh was Irving Stone’s novel Lust for Life (1934), and Vincente Minnelli’s film adaptation starring Kirk Douglas (1956), which helped shape Americans’ popular understanding of the artist.

“How Van Gogh became a household name in the United States is a fascinating, largely untold story,” said Jill Shaw, Head of the James Pearson Duffy Department of Modern and Contemporary Art and Rebecca A. Boylan and Thomas W. Sidlik Curator of European Art, 1850 –1970, at the DIA. “Van Gogh in America examines the landmark moments and trajectory of the artist becoming fully integrated within the American collective imagination, even though he never set foot in the United States."

The Exhibition

Van Gogh in America is arranged in a narrative fashion spanning 9 galleries, starting with Van Gogh’s Chair (opens in a new tab)(1888; The National Gallery, London):

Starry Night (1888) – on loan from the Musée d'Orsay in Paris – is the newest addition to its Van Gogh in America exhibition, which will run from October 2, 2022 to January 22, 2023 only at the DIA. Featuring more than 70 works by the famed artist, the groundbreaking exhibition is the first ever devoted to Van Gogh’s introduction and early reception in America. Tickets will go on sale this summer.

Starry Night – also known as Starry Night Over the Rhône – is one of two iconic paintings including the nighttime sky that Van Gogh created while living in the French city of Arles from 1888 to 1889. The beloved work captures a clear, star-filled night sky and the reflections of gas lighting over an illuminated Rhône(opens in a new tab) River in Arles with a couple strolling along its banks in the foreground. Starry Night is important to the introduction of Van Gogh’s work to the United States for its pivotal role in the iconic film Lust for Life (1956; directed by Vincente Minnelli). The masterpiece will be on view in the U.S. for the first time since 2011, and is one of three Van Gogh works on loan from the Musée d'Orsay for the DIA exhibition.

Van Gogh in America will be the largest-scale Van Gogh exhibition in America in a generation, featuring paintings, drawings, and prints by Van Gogh from museums and private collections worldwide. Visitors will also “journey” through the defining moments, people, and experiences that catapulted Van Gogh’s work to widespread acclaim in the U.S.

Van Gogh in America reveals the story of how America’s view of Van Gogh’s work evolved during the first half of the 20th century and his rise to cultural prominence in the United States. Despite his work appearing in over 50 group shows during the two decades following his American debut in the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art (commonly known as the Armory Show), it was not until 1935 that Van Gogh was the subject of a solo museum exhibition in the United States. Around the same time, Irving Stone’s novel Lust for Life was published, and its adaptation into film in 1956 shaped and began to solidify America’s popular understanding of Van Gogh.

Major highlights include:

"Two Peasants Digging," 1889, Vincent van Gogh, Dutch; oil on canvas. Stedelijk Musuem, Amsterdam, A411.

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890). Lullaby:Madame Augustine Roulin Rocking a Cradle (La Berceuse), 1889. Oil on canvas; 36 1/2 x 28 5/8 in. (92.7 x 72.7 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of John T. Spaulding, 48.548.

Vincent van Gogh

Zundert 1853 – 1890 Auvers-sur-Oise

WALLRAF-RICHARTZ-MUSEUM & FONDATION CORBOUD

The Drawbridge

1888, Oil on canvas, 49.5 x 64.5 cm

Acquired in 1911

Inv. no. WRM 1197

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

A full-length, illustrated catalogue with essays by Rachel Esner, Joost van der Hoeven, Julia Krikke, Jill Shaw, Susan Alyson Stein, Chris Stolwijk, and Roelie Zwikker, and a chronology by Dorota Chudzicka will accompany the exhibition.

A fascinating exploration of the introduction of Vincent van Gogh’s work to the United States one hundred years later

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) is one of the most iconic artists in the world, and how he became a household name in the United States is a fascinating, largely untold story. Van Gogh in America details the early reception of the artist’s work by American private collectors, civic institutions, and the general public from the time his work was first exhibited in the United States at the 1913 Armory Show up to his first retrospective in an American museum at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1935, and beyond. The driving force behind this project, the Detroit Institute of Arts, was the very first American public museum to purchase a Van Gogh painting, his Self-Portrait, in 1922, and this publication marks the centenary of that event.

Leading Van Gogh scholars chronicle the considerable efforts made by early promoters of modernism in the United States and Europe, including the Van Gogh family, Helene Kröller-Müller, numerous dealers, collectors, curators, and artists, private and public institutions, and even Hollywood, to frame the artist’s biography and introduce his art to America.

That is Linda Stone-Ferrier’s conclusion after analyzing a range of 17th-century Dutch paintings in a new context: that of the neighborhood. Her book, “The Little Street: The Neighborhood in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art and Culture,” is just out from Yale University Press after a 14-year process of research, writing and editing.

A professor of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art in KU’s Kress Foundation Department of Art History, Stone-Ferrier realized she would begin research for a book like “The Little Street” when, by chance, she read an article about 17th-century Netherlandish neighborhoods by the sociologist Herman Roodenburg.

“I knew no art historian had ever talked about the neighborhood, which Roodenburg made very clear was a significant organizing unit for social control and social exchange,” Stone-Ferrier said. “No art historians of Dutch art had ever addressed the neighborhood as an interpretive context for the study of Dutch paintings.”

In the book’s introduction, she writes that studies by art historians tend to silo works by subject matter, like landscapes or scenes of daily life, “presum(ing) that each category raises interpretive issues distinct from the others. In a revision of that paradigm, I argue that certain seemingly diverse subjects share the neighborhood as a meaningful context for analysis.”

In addition, Stone-Ferrier writes, her book challenges scholars’ assumptions that categorize “imagery in paintings within a binary construct of ‘private,’ understood as the female domestic sphere, versus ‘public,’ synonymous with the male domain of the city ...”

The neighborhood was a “liminal space” between home and city that encompassed people of every gender, religion, social class, nationality and political persuasion, she writes. In fact, Dutch citizens of the 1600s were required to officially belong to and participate in their neighborhood organizations – much like today’s homes associations – which collected membership dues, enforced neighborhood rules, and hosted mandatory meetings and annual group meals. Thanks to some exquisite recordkeeping from centuries ago and today’s digital resources, Stone-Ferrier was able to research, among other things, relevant subjects of paintings and the identity and professions of Dutch citizenry who owned them that informed her research. Art collecting was important, Stone-Ferrier said, to a broad and deep urban middle class whose wealth was generated by such trading enterprises as the Dutch East and West India companies.

And it's clear, from an analysis of that art and an array of documents, that what was going on down the street and around the corner was important to Dutch people of that time – just as it is to people in neighborhoods around the world today.

“Honor is the word the Dutch used in in their neighborhood regulations and in other contexts, too,” Stone-Ferrier said. “Honor had to do with how one behaved. To act honorably in all endeavors -- personally, at home, in your business -- was valued highly. An individual's honor or dishonor reflected on that of the whole neighborhood. That was an integral tie. That's why there was gossip and documented witness statements regarding the behavior of one’s neighbors.”

One chapter is subtitled “Glimpses, Glances, and Gossip” because — like today -- not only are people curious about what the neighbor across the street is doing in his driveway, or what is going on with those Rottweilers around the corner, but they want to make sure people are not misbehaving or breaking communal rules.

Paintings showing scenes of people upholding neighborhood virtues both reflected and reinforced those values, Stone-Ferrier writes.

Hammer Museum

October 1 – December 31, 2022

The Hammer Museum at UCLA presents Picasso Cut Papers, an exhibition about an important yet little-known aspect of the practice of Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). This exhibition features some of Pablo Picasso’s most whimsical and intriguing works made on paper and in paper, alongside a select group of sculptures in sheet metal. Cut papers were created as independent works of art, as exploratory pieces in relation to works in other mediums, as models for Picasso’s fabricators, and as gifts or games for family and friends.

Pablo Picasso, Female nude, Barcelona or Paris, 1902–03. Pen and sepia ink on paper pasted onto electric-blue glazed paper. 7 5/8 × 13 5/16 in. (19.3 × 33.8 cm). Museu Picasso, Barcelona. Gift of Pablo Picasso, 1970 © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York;

Although the artist rarely sold or exhibited them during his lifetime, he signed, dated, and archived them just as he did his works in other mediums. Many examples have been stored flat or disassembled in portfolios until now and will regain their original three-dimensional forms when presented in the exhibition. This survey spans Picasso’s entire career, from his first cut papers, made in 1890, at nine years of age, through the 1960s, with works he made while in his eighties. Picasso Cut Papers will be on view from October 1 to December 31, 2022.

There are approximately 100 works in the exhibition, many of which have never before been displayed in public, with loans coming principally from the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte, the Picasso estate, and the Musée national Picasso in Paris. Major loans have also been granted by the Museu Picasso in Barcelona; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and the collection of Gail and Tony Ganz.

“Given our major collection of works on paper from the Renaissance to the present, the Hammer has a long-standing commitment to presenting both historical and contemporary exhibitions of works on paper. We are thrilled to be organizing the first exhibition devoted solely to Pablo Picasso’s inventive cut papers, many of which have never been exhibited. Picasso Cut Papers will also be the first international loan exhibition to occupy our new Works on Paper Gallery.” said Hammer Museum director Ann Philbin.

Picasso played with the versatility of paper and its ability to be folded and molded, attempting to create volume where it is not otherwise perceived. The cut papers embody the artist’s ongoing experiments in breaking down the traditional barriers between drawing, painting, and sculpture, extending into the fields of photography, moving images, and live performance. Picasso Cut Papers is organized loosely chronologically, according to the following sectios:

• Silhouettes • Contours • Cut, Pinned, and Pasted Papers • Torn and Perforated Papers • Shadow Papers • Sculpted Papers • Divertissements • Masks • Diurnes

CREDITS

Picasso Cut Papers is organized by Cynthia Burlingham, deputy director, curatorial affairs, and Allegra Pesenti, independent curator, former associate director and senior curator, Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. The exhibition is organized with the exceptional support of the Musée national Picasso–Paris.

CATALOGUE

The first publication to focus solely on Picasso’s cut papers, this book features many works reproduced for the first time with newly commissioned photography, alongside new scholarship on a little-known aspect of one of the 20th century’s most pivotal practices. It contributes to the ongoing discourse surrounding innovation and abstraction at the roots of modern art. Also featured is a photo section that surveys Picasso’s engagement with cut paper and sculpture over the decades and documents his practice of cutting paper, both in and out of the studio, with family, friends, and collaborators.

The book features a text by Allegra Pesenti and is edited by Cynthia Burlingham and Pesenti. It is published by DelMonico Books • D.A.P and designed by Miko McGinty and Rita Jules.

Also see People Come First

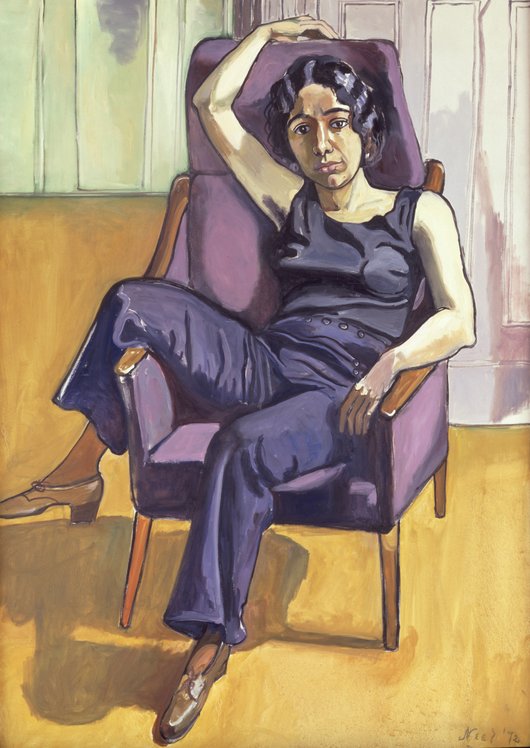

Image: Alice Neel, Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), 1972

Image: Alice Neel, Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), 1972

An Exhibition Centered on Women in Surrealism

Over the Past Century

On View at Phillips, 432 Park Avenue

From 21 October – 22 November

Kay Sage Secret Voyage of a Spark, 1944 |

Emily Mae Smith Gleaner Odalisque, 2019 |

Phillips is proud to announce The Virtues of Rebellion, an upcoming exhibition through PHILLIPS X which will explore the creative output of women Surrealists from the first half of the 20th century and the artists working today that mine this rich legacy. Coinciding with the marquee 20th Century and Contemporary auctions across all three major houses in New York, artworks for sale and on loan will be displayed in our 432 Park Ave galleries from 21 October – 22 November.

Jeremiah Evarts, Deputy Chairman, Americas & Senior International Specialist, said, “André Breton’s seminal movement, which first took hold in the late 1920s in Paris, served to inspire a generation across the globe, many of whom did not receive the cultural or institutional recognition they so rightly deserved at the time. Recent exhibitions, including Surrealism Beyond Borders at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Tate as well as Milk of Dreams at this year’s Venice Biennale, expand the definition of Surrealism beyond the small group of Paris-based men that have historically represented the movement. We look forward to continuing this necessary exploration of the lesser-known historical Surrealists and their contemporary counterparts.”

Alexander Weinstock, Associate, Private Sales, added, “As with our auctions, we are thrilled to continue Phillips tradition of curating new dialogues between disparate groups of artists across space and time. Spanning the mediums of painting, sculpture, and photography, we look forward to creating a juxtaposition of some of the most exciting women artists working today alongside their Surrealist predecessors.”

Seeking to bridge the gap between dream and reality, past and present, Surrealist artists such as Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Dorothea Tanning, Kay Sage, and Leonor Fini employed a range of visual approaches that united in visions of fantastical worlds deeply rooted in historical and spiritual significance. Against a broad swath of socio-political backdrops, each played a crucial role in the evolution of twentieth-century Modernism. Today, a new generation of painters including Emily Mae Smith, Julie Curtiss and Louise Bonnet, incorporate a similar surrealist lexicon into their art-making.

Exhibition viewing: 21 October – 22 November

Location: 432 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10022

Click here for more information: www.phillips.com/store/virtues-of-rebellion

Dorothea Tanning La Truite au bleu (Poached Trout), 1952

|

Emily Mae Smith Oh, Barb, 2017 | |

Anna Weyant Stepped on a Spider, 2020 |

Remedios Varo Ojos sobre la mesa, 1935 | |

29 September 2022 – 15 January 2023

The Mauritshuis will round off its bicentenary year with a very special exhibition, featuring ten paintings by Dutch masters from The Frick Collection in New York. For the first time in its existence, the American museum will loan these items to a European museum, while its own building is undergoing renovation. One of the paintings that will temporarily exchange New York for The Hague is Rembrandt’s acclaimed Self-portrait of 1658, a painting of exceptional quality. Rembrandt painted many self-portraits, but this one is acknowledged by experts to be one of the most impressive of all. In addition, the museum may welcome a Vermeer, Hals, Ruysdael and Cuyp, among others. ≈

Masterpiece by Frans Hals

The third top piece flown over from New York is Portrait of a man by Frans Hals. Nothing is known about the commissioner: the portrait bears no family crests or inscriptions mentioning age. What is known is that Hals made this portrait towards the end of his life. He was then in his late seventies, and used a loose and spontaneous painting technique. The portrait has a lively character due to the broad strokes of white paint on the shirt, collar and cuffs.

Edward Hopper’s New York, on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art from October 19, 2022, through March 5, 2023, offers an unprecedented examination of Hopper’s life and work in the city that he called home for nearly six decades (1908–67). The exhibition charts the artist’s enduring fascination with the city through more than 200 paintings, watercolors, prints, and drawings from the Whitney’s preeminent collection of Hopper’s work, loans from public and private collections, and archival materials including printed ephemera, correspondence, photographs, and notebooks. From early sketches to paintings from late in his career, Edward Hopper’s New York reveals a vision of the metropolis that is as much a manifestation of Hopper himself as it is a record of a changing city, whose perpetual and sometimes tense reinvention feels particularly relevant today.

Instantly recognizable paintings featured in the exhibition, such as Automat (1927), Early Sunday Morning (1930), Room in New York (1932), New York Movie (1939), and Morning Sun (1952), are joined by lesser-known yet critically important compositions including a series of watercolors of New York rooftops and bridges and the painting City Roofs (1932).

“Edward Hopper’s New York offers a remarkable opportunity to celebrate an ever-changing yet timeless city through the work of an American icon,” says Adam D. Weinberg, the Alice Pratt Brown Director of the Whitney Museum. “As New York bounces back after two challenging years of global pandemic, this exhibition reconsiders the life and work of Edward Hopper, serves as a barometer of our times, and introduces a new generation of audiences to Hopper’s work by a new generation of scholars. This exhibition offers fresh perspectives and radical new insights.”

Edward Hopper’s New York is organized by Kim Conaty, Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawings and Prints, with Melinda Lang, Senior Curatorial Assistant, at the Whitney.

Edward Hopper and New York City

Born in the Hudson River town of Nyack, New York, in 1882, Hopper first visited Manhattan on family day trips. After completing high school, he commuted to the city by ferry to attend the New York School of Illustration and the New York School of Art. In 1908 he moved to the city, and he spent the majority of his life, from 1913 until his death in 1967, living and working in a top-floor apartment at 3 Washington Square North in Greenwich Village. He was joined there by his wife, the artist Josephine (Jo) Verstille Nivison, following their marriage in 1924. Jo played a crucial supportive and collaborative role in Hopper’s practice, serving as his longstanding model and chief record-keeper. A selection of Jo’s watercolors, capturing their Washington Square home, are included in Edward Hopper’s New York.

“Hopper lived most of his life right here, only blocks from where the Whitney stands today,” says Conaty. “He experienced the same streets and witnessed the incessant cycles of demolition and construction that continue today, as New York reinvents itself again and again. Yet, as few others have done so poignantly, Hopper captured a city that was both changing and changeless, a particular place in time and one distinctly shaped by his imagination. Seeing his work through this lens opens new pathways for exploring even Hopper’s most iconic works.”

Over the course of his career, Hopper observed the city assiduously, honing his understanding of its built environment and the particularities of the modern urban experience. During this time, New York underwent tremendous development—skyscrapers reached record-breaking heights,

construction sites roared across the five boroughs, and the increasingly diverse population boomed—yet Hopper’s depictions remained human-scale and largely unpopulated. Deliberately avoiding the famous skyline and picturesque landmarks such as the Brooklyn Bridge and the Empire State Building, Hopper instead turned his attention to unsung utilitarian structures and out-of-the-way corners, drawn to the collisions of new and old, civic and residential, public and private that captured the paradoxes of the changing city.

Edward Hopper’s New York: The Exhibition

Organized in thematic chapters spanning Hopper’s entire career, the installation comprises eight sections including four expansive gallery spaces showcasing many of Hopper’s most celebrated paintings and four pavilions that focus on key topics through dynamic groupings of paintings, works on paper, and archival materials, many of which have rarely been exhibited to the public.

Edward Hopper’s New York begins with early sketches and paintings from the artist’s first years traveling into and around the city, from 1899 to 1915, as he grew from a commuting art student to a Greenwich Village resident. In Moving Train (c. 1900), Tugboat with Black Smokestack (1908), and El Station (1908) he observed the ways people occupied and moved through space within a dramatically developing urban environment.

Although Hopper aspired to recognition as a painter, his first successes came in print through his illustrations and etchings, an important history featured in a section of the exhibition titled “The City in Print.” His artworks for illustrations and published commissions for magazines and advertisements often featured urban motifs inspired by New York—theaters, restaurants, offices, and city dwellers—that would become foundational to his art. During this early period, he also consolidated many of his impressions of New York through etchings like East Side Interior (1922) and The Open Window (c. 1918–19), which preview the dramatic use of light that has become synonymous with Hopper’s work.

“The Window,” the next section, focuses on this enduring motif for Hopper— one that he explored with great interest in his city scenes. While strolling New York’s streets and riding its elevated trains, Hopper was particularly drawn to the fluid boundaries between public and private space in a city where all aspects of everyday life—from goods in a storefront display to unguarded moments in a café—are equally exposed. In paintings on view such as Automat (1927), Night Windows (1928), and Room in Brooklyn (1932), Hopper imagines the unlimited compositional and narrative possibilities of the city’s windowed facades, the potential for looking and being looked at, and the discomfiting awareness of being alone in a crowd.

Edward Hopper’s New York presents, for the first time together, the artist's panoramic cityscapes, installed as a group in a section of the exhibition titled “The Horizontal City.” Early Sunday Morning (1930), Manhattan Bridge Loop (1928), Blackwell’s Island (1928), Apartment Houses, East River (c. 1930), and Macomb’s Dam Bridge (1935), five paintings made between 1928 and 1935, all share nearly identical dimensions and format. Seen together, they offer invaluable insight into Hopper’s contrarian vision of the growing city at a time when New York was increasingly defined by its relentless skyward development.

“Washington Square” highlights the importance of Hopper’s neighborhood as his home and muse for nearly 55 years. Paintings like City Roofs (1932) and November, Washington Square (1932/1959) show Hopper’s fascination with the city views visible from his windows and his rooftop, and a rare series of watercolors—a practice he generally reserved for his travels to New England and elsewhere—reveals how attuned he was to the spatial dynamics and subtleties of the city’s built environment. As documented in the exhibited correspondence and notebooks, the Hoppers were fierce advocates of Washington Square, and they argued tirelessly for the preservation of their neighborhood as a haven for artists and as one of the city’s cultural landmarks.

“Theater,” a particularly revealing gallery in the exhibition, explores Hopper’s passion for the stage and the critical role it played as an active mode of spectatorship and source of visual inspiration. This section includes archival items like the Hoppers’ preserved ticket stubs and theatergoing notebooks and highlights the ways that theater spaces and set design influenced Hopper’s compositions through works like Two on the Aisle (1927) and The Sheridan Theatre (1937). Additionally, the presentation of New York Movie (1939) and a group of its preparatory studies along with figural sketches for other paintings reveal the Hoppers’ collaborative scene staging, in which Jo played an active part as model.

Throughout his career, Hopper explored the city with sketchbook in hand, recording his observations through drawing, a practice highlighted in this section of the exhibition. A large selection of his sketches and preparatory studies on view in “Sketching New York” chart Hopper’s favored locations across the city, many of which the artist returned to again and again in order to capture different impressions that he could later explore on canvas.

Finally, in “Reality and Fantasy,” a group of ambitious late paintings, characterized by radically simplified geometry and uncanny, dreamlike settings, reveal how New York increasingly served as a stage set or backdrop for Hopper’s evocative distillations of urban experience. In works such as Morning in a City (1944), Sunlight on Brownstones (1956), and Sunlight in a Cafeteria (1958), Hopper created compositions that depart from specific sites while still tapping into urban sensations, reflecting his desire, as noted in his personal journal “Notes on Painting”, to create a “realistic art from which fantasy can grow.”

THE CITY IN PRINT

Although Hopper aspired to recognition as a painter, his first successes came in print, through his illustrations and etchings. Having trained in commercial art in his student years, he found work as an illustrator after leaving school in 1906. By this time, New York had established itself as the advertising and publishing center of the United States, and in the 1910s and 1920s Hopper received a steady flow of assignments, which helped him earn a living and supported his fine art practice. His illustrations often featured urban motifs inspired by New York—theaters, restaurants, offices, and city dwellers—that would become foundational to his art.

Intrigued by the creative possibilities of printmaking, Hopper spent much of his free time between 1915 and the early 1920s refining his etching techniques. He acquired a press for his studio in 1916 and began to exhibit and sell his prints, many of which also took inspiration from city subjects. For Hopper, the print medium offered a critical opportunity to sharpen his compositional skills and to experiment with light and shadow in black and white.

Night Shadows, 1921 Etching Sheet: 12 x 15 15/16 in. (30.5 x 40.5 cm); plate: 6 7/8 x 8 1/4 in. (17.5 x 21 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1047 |

The Lonely House, 1922 Etching Sheet: 13 3/8 x 16 11/16 in. (34 x 42.4 cm); plate: 7 7/8 x 9 3/4 in. (20 x 24.8 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1040 |

Edward Hopper, New York and Its Houses, c. 1906–10. Watercolor, ink, and graphite pencil on paper, 21 13/16 × 14 13/16 in. (55.4 × 37.6 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1347. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Hopper, A Theater Entrance, 1906–10. Watercolor, ink, and graphite pencil on paper, 19 11/16 × 14 3/4 in. (50 × 37.5 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1378. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York |

THE WINDOW

Hopper spent hours strolling New York’s sidewalks, riding its elevated trains, patronizing its eating establishments, and attending the theater, always on the lookout for new subjects. He was particularly drawn to the fluid boundaries between public and private space in a city where all aspects of everyday life—from goods in a storefront display to unguarded moments in a café—are equally exposed. The window became one of Hopper’s most enduring symbols, and he exploited its potential to depict the exterior and interior of a building simultaneously, a viewing experience he described as a “common visual sensation.”

Hopper’s interiors suggest the vulnerability of private life in the densely populated metropolis. In Night Windows (1928) and Room in New York (1932), for example, he captures the experience of the city after nightfall as illuminated spaces became a sort of urban theater for passersby. For Hopper, New York’s windowed facades served as dynamic structuring devices that he employed in compositions throughout his career.

Edward Hopper, Automat, 1927. Oil on canvas,281/8×35in.(71.4×88.9cm). Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa; purchased with funds from the EdmundsonArtFoundation,Inc.©2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Rich Sanders, Des

Edward Hopper, Drug Store, 1927. Oil oncanvas,29×401/8in.(73.7×101.9 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; bequest of John T. Spaulding. © 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

THE HORIZONTAL CITY

Five paintings made between 1928 and 1935—Manhattan Bridge Loop; Blackwell’s Island; Macomb’s Dam Bridge; Apartment Houses, East River; and Early Sunday Morning—share nearly identical dimensions and the same panoramic format. Collectively, these paintings provide invaluable insight into Hopper’s contrarian vision of a horizontal city; as Alfred H. Barr observed of Hopper’s work in 1933: “His indifference to skyscrapers is remarkable in a painter of New York architecture.”

Describing his aims in Manhattan Bridge Loop, Hopper explained that the painting’s horizontal composition was an attempt to give “a sensation of great lateral extent” and bring attention to the cityscape beyond the frame; “I just never cared for the vertical,” he later quipped. His depictions of the wide spans of the city’s bridges, its industrial landscapes, and its low-slung buildings elevate the quotidian and prosaic over the iconic, offering a powerful counterpoint to the awe-inspiring views of the New York skyline celebrated in the news and in works by many of his contemporaries.

Edward Hopper (American, 1882-1967). Macomb's Dam Bridge, 1935. Oil on canvas, 35 x 60 3/16in. (88.9 x 152.9cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Mary T. Cockcroft, 57.145. © artist or artist's estate (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 57.145_SL1.jpg

WASHINGTON SQUARE

Hopper moved to a modest top-floor residence at 3 Washington Square North in Greenwich Village in 1913, and was joined there by the artist Josephine (Jo) Verstille Nivison Hopper upon their marriage in 1924. When the Hoppers moved across the hall in 1932 to a larger apartment overlooking Washington Square Park, they devoted more space to artmaking than to their domestic accommodations.

Even as she pursued her own work, Jo played a crucial supportive role in Edward’s practice as his long-standing model and chief record- keeper. The intersections between work and home life were fluid and the dynamics between the two artists challenging at times, but Edward and Jo remained in that apartment until their deaths in 1967 and 1968, respectively.

In his first years on Washington Square, Edward took great interest in the cityscape visible from his windows and his rooftop. Jo, for her part, often selected interior subjects, from the pot- bellied stove to the stairwell that led the seventy-four steps up to the apartment. Through their front windows, the Hoppers witnessed the incessant cycles of demolition and construction as nineteenth- century buildings like their own were torn down to make way for new structures. During their many decades in Greenwich Village they advocated for the preservation of the neighborhood as a haven for artists and as one of the city’s cultural landmarks.

THEATER

Hopper was passionate about the theater, and his work underscores the critical role it played as an active mode of spectatorship and a wellspring of visual inspiration. He and Jo frequented local establishments like the Sheridan Theatre, a nearby movie house, as well as the theaters clustered in Times Square’s growing entertainment district, as documented by the numerous ticket stubs they methodically annotated and kept. Hopper set several compositions within theater interiors, focusing not on the action on stage or screen but instead on transitional moments and private interludes—an usher lost in thought, a lone theatergoer at the back of a cinema. Hopper’s experiences in these venues, in which real and fictive worlds are divided only by a proscenium, surely contributed to many of his stagelike compositions.

Back in the studio, Hopper’s painting process often called for its own form of theater. With a background in acting as a member of the Washington Square Players, Jo collaborated with Edward, helping him source props and posing as various figure types. For each painting, Edward gradually transformed Jo’s likeness into a distinct character through a succession of preparatory studies, once remarking that the final work “doesn’t look anything like her usually.”

|REALITY AND FANTASY

In his personal journal “Notes on Painting” from around 1950, Hopper described his desire to create a “realistic art from which fantasy can grow.” At a time when many artists in New York had grown skeptical of figurative painting and aligned themselves with new modes of abstraction, Hopper’s depictions of cafeterias, theaters, offices, and apartment bedrooms occupied a potent middle ground, with their radically simplified geometry and uncanny, dreamlike settings.

In these ambitious late works, Hopper often incorporated solitary figures or small groups of individuals set in generic urban spaces that nonetheless capture particularities of the city’s built environment— a brownstone abutting a public park, a cafeteria overlooking another building’s facade, a neighbor’s window seen through one’s own. Through these scenes, New York served as a stage set or backdrop for Hopper’s explorations of what he described as the “vast and varied realm” of one’s inner life.

For more information about the artworks included in this exhibition, please see Conaty’s catalogue essay Approaching a City: Hopper and New York.

Edward Hopper and the Whitney Museum of American Art

Edward Hopper’s career and work have been a touchstone for the Whitney since before the Museum was founded. In 1920, at the age of thirty-seven, Hopper had his first solo exhibition at the Whitney Studio Club. He was included in a number of exhibitions there before it closed in 1928 to make way for the Whitney Museum of American Art, which opened in 1931. Hopper’s work appeared in the inaugural Whitney Biennial in 1932 and in twenty-nine subsequent Biennials and Annuals through 1965, as well as several group exhibitions. The Whitney was among the first museums to acquire a Hopper painting for its collection. In 1968, Hopper’s widow, the artist Josephine Nivison Hopper bequeathed the entirety of his artistic holdings–2,500 paintings, watercolors, prints, and drawings–and many of her own works from their Washington Square studio residence. Today the Whitney’s collection holds over 3,100 works by Hopper, more than any other museum in the world.

“Given Hopper’s status in the Whitney's history and within the ranks of American art history, this periodic reconsideration and regular reckoning is imperative and a critical obligation,” says Weinberg.

Catalogue

An accompanying exhibition catalogue, Edward Hopper’s New York, published by the Whitney and distributed by Yale University Press, features essays by curator Kim Conaty, writer and critic Kirsty Bell, scholar Darby English, and artist David Hartt. Alongside these essays are four focused texts that draw upon the resources made newly available through the Museum’s Sanborn Hopper Archive. These contributions are authored by Whitney staff members who have been working closely with the archive, including Farris Wahbeh, Benjamin and Irma Weiss Director of Research Resources; Jennie Goldstein, Assistant Curator; Melinda Lang, Senior Curatorial Assistant; and David Crane, former Curatorial Fellow. The publication features more than three hundred illustrations and fresh insights from authoritative and emerging scholars.

Bonhams present sfor sale the entire collection of Melvin S. Rosenthal featuring the finest examples of art from the 20th century on November 16 in New York. Mr. Rosenthal's collection includes renowned artists who had the greatest impact on modern and contemporary art. The dedicated sale will include nine works by 20th century masters such as Hans Hofmann, Robert Motherwell, and Ed Ruscha.

Mr. Rosenthal was Executive Vice President of the largest decorative pillow company in North America whose business travels took him from India, Peru, Japan, Taiwan, and China. Over the past 30 years, Mr. Rosenthal's keen eye for design and art, amassed a collection of some of the most influential Contemporary artists which set off his spectacular homes in Los Angeles and Malibu. Mr. Rosenthal built and designed his homes around his art collection, from the Ruscha over the mantle that mirrors the sunset from his Malibu beach house to the Hofmann in Los Angeles that plays opposite the view of the Hollywood Sign.

"It's a collection of the most impeccable quality and clearly a result of Mr. Rosenthal's disposition – from his lifestyle and outlook on life to his keen sense of design and style," commented Ralph Taylor, Global Head of Post-War & Contemporary Art for Bonhams. "This equipped him with the confidence to make bold decisions in his art collecting."

A striking masterpiece painting by Hans Hofmann (1880-1966), Let There Be Light (And the Sun Beautiful as She Was and Pregnant – Scattered Her's Colours All over the Earth) (1955-1961), estimated at $3,000,000-5,000,000, was made over the course of several years by the artist. Hofmann's confident gestures are seen as he shaped an array of oranges and reds around a yellow sun, as if not only light and color, but brushwork and paint all come from the sun, spreading out over the surface of the canvas as light and color spread out over the landscape.

The dramatic strokes and bold composition of Robert Motherwell's (1915-1991) Untitled (Elegy) (1962) is an almost calligraphic language of emotion. Motherwell's powerful and comprehensive series, known as Elegies to the Spanish Republic, are widely recognized and this particular work remained with the artist until his death (estimate: $1,000,000-1,500,000). The Eighties (1980) by Ed Ruscha (b. 1937), estimated at $800,000-1,200,000, is another example that suggests an orange, red sunset spreading over the ocean.

Additional works included in the sale:

• Site Avec 8 Personnages (E39) (1981) by Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985) is estimated at $150,000 – 250,000.

• Plutusia IV (1995) by Frank Stella (B. 1936) is estimated at $60,000 – 80,000.

• Loop (1970) by Adolph Gottlieb (1903-1974) is estimated at $50,000 – 70,000.

• Untitled (1992-1993) by Frederick Eversley (B. 1941) is estimated at $120,000 – 180,000.

• Green and Yellow Squash (1997) by Donald Sultan (B. 1951) is estimated at $20,000 – 30,000.

• Tête de jeune fille (1913) by Jean Metzinger (1883-1956) is estimated at $60,000 – 80,000.

Cy Twombly

Untitled, 2005

Estimate: $35,000,000 – 45,000,000

On 15 November, Phillips’ Evening Sale of 20th Century & Contemporary Art in New York will be led by Cy Twombly’s monumental Untitled, 2005. With exceptional provenance and estimated at $35-45 million, Untitled is a masterpiece from one of Twombly’s last epic series that found its inception in his blackboards and crystallized in the three discrete suites of paintings collectively known as the Bacchus series. The Bacchus paintings began in 2003 amidst the US invasion of Iraq and culminated in 2008 when the artist donated three of the monumental works to the Tate Modern, London. The present work is the second-largest canvas from the 2005 series which were exhibited under the collective title Bacchus Psilax Mainomenos. Recalling the artist’s earlier Blackboard paintings from the late 1960s with its continuous looping forms, the Bacchus series revisits this earlier motif with a renewed vigor and energy which manifests on the surface of Untitled.

Jean-Paul Engelen, President, Americas, and Worldwide Co-Head of 20th Century & Contemporary Art, said, “With the top ten auction prices for works by Cy Twombly having all been set in the past eight years, it’s clear that the market is stronger than ever. At sixteen feet wide, Untitled is among the largest of Twombly’s works to ever appear at auction, with its subject referring to the dual nature of the ancient Greek and Roman god of wine, intoxication, and debauchery. The work hails from the series that marked Twombly’s ultimate artistic expression at the summit of his career and we are proud to offer this masterpiece as the highlight of our Fall season.”

The translation of Bacchus Psilax Mainomenos references both the exuberance and rage that alcohol can bring, with Tate Director Nicholas Serota remarking about the paintings, “They relate obviously to the god of wine and to abandon, and luxuriance, and freedom.” The work also recalls one of the most violent and emotionally stirring moments of Iliad, when the Greek hero, Achilles, kills the Trojan prince, Hector, dragging his corpse in circles through the desert around the walled city of Troy—just as Twombly’s red line colors the ground of Untitled.

The repetition of the mythical theme in Twombly’s work, particularly the continued invocation of Bacchus across the years, finds its stylistic parallel in Twombly’s signature, circular, scrawling gesture. Two extremes rise and fall within one ancient deity, cycling, one over the other, just as Twombly’s brush turns across the surface of Untitled. This gesture appeared in the artist’s earlier Blackboard series of the 1960s, making a reprise in Untitled, though with a much wilder red spiral. The red line of Untitled is rich with emotive movement as the spiral turns and drips across the canvas, the result of Twombly likely using his whole body, swinging the brush, which he attached to a long pole, across the canvas.

Marc Chagall

Le Père, 1911

Estimate: $6-8 Million

On 15 November, Phillips will offer Marc Chagall’s Le Père in the New York Evening Sale of 20th Century & Contemporary Art. Executed in 1911, during a transformative period in the artist’s career, the painting is among fifteen works of art that the French Government have restituted earlier this year — part of an ongoing effort to return works in its museums that were wrongfully seized by the Nazi Party during World War II. A long-treasured part of the collection of David Cender, a musical instrument-maker from Łódź, Poland, the work was taken from him in 1940 before he was sent to Auschwitz with his family. By 1966, it had been reacquired by Chagall himself, who held a particular affinity for the painting, as it portrays his beloved father. In 1988, the Musée national d’art moderne, Centre national d’art et de culture Georges-Pompidou in Paris received the painting by dation from Chagall’s estate. Estimated at $6-8 million, this is the first work from this group of fifteen restituted artworks to appear at auction.

Jeremiah Evarts, Deputy Chairman, Americas, and Senior International Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, said, “Phillips is honored to play a role in the incredible journey that this painting has taken over the last century. Chagall’s legacy is vital to the history of Western art, with Le Père standing as a masterwork within the art historical canon. The heart-wrenching and compelling history of the painting after its completion, all leading to the wonderful news of its return to the Cender Family makes the story of Le Père all the more fascinating. We commend the French government for their dedication in returning such important works in their collection to the families of their rightful owners.”

Le Père is a rare, dynamic portrait which signifies the artist’s pivotal transition from art student in Saint Petersburg to one of the defining figures of European Modernism. During the winter of 1911-1912, Chagall moved into La Ruche, an artists’ commune on the outskirts of Montparnasse. The works he created over the next three years are among the most highly regarded of his career, with his portraits bearing particular significance. Throughout his lifetime, Chagall revitalized the inherited traditions of portrait painting. He painted dreamy and fantastical portraits of lovers, religious figures, villagers, and his beloved family throughout his seven-decade career. Le Père is an intimate portrait of the artist’s father Zahar, a quiet and shy man who spent his entire life working in the same manual labor job. Portraits of the artist’s father are rare within Chagall’s oeuvre. Far from the generalized symbols of lovers that dominated much of his later paintings, this early work is a remarkably personal and heartfelt depiction.

The early owner of this painting, David Cender, was a prominent musical instrument maker in Łódź, Poland who created pieces of the highest class for the eminent musicians of the era, as well as being a musician and music teacher in his own right. In 1939, David married Ruta Zylbersztajn and soon after their daughter Bluma was born. Prior to 1939, 34% of Łódź's 665,000 inhabitants were Jewish, and the city was a thriving center of Jewish culture. In the spring of 1940, David Cender and his family were forced to leave their home and move into the ghetto, leaving behind numerous valuable possessions including their collection of artwork and musical instruments. While David survived the war, his wife, daughter, and other relatives were killed at Auschwitz.

Chagall reacquired the work by 1966 and it remained in his personal collection through the remainder of his life. In 1988, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre national d’art et de culture Georges-Pompidou in Paris received by dation from the Chagall estate Le Père along with 45 paintings and 406 drawings and gouaches. Ten years later, the work was deposited into the Musée d'art et d'histoire du Judaïsme in Paris, where it was been on view for twenty-four years.

Earlier this year, on 25 January 2022, the French National Assembly unanimously passed a bill approving the return of the fifteen works of art; the bill was then passed by its Senate on 15 February. The Minister of Culture, Roselyne Bachelot, praised the decision saying that not restituting the works was “the denial of the humanity [of these Jewish families], their memory, their memories.” The historic passing of this bill marks the first time in more than seventy years that a government initiated the restitution of works in public collections looted during World War II or acquired through anti-Semitic persecutions.

On April 1, 2022, Le Père was returned to the heirs of David Cender by the Parlement français in Paris.

Coming to auction for the first time, Le Père is a treasured and rare example from the artist’s early oeuvre. It’s inclusion in this landmark restitution signifies a historic moment in cultural history.

Auction: 15 November 2022

Auction viewing: 5-15 November 2022

Location: 432 Park Avenue, New York, NY

Click here for more information: https://www.phillips.com/auctions/auction/NY01072

|

|

|

|

|

Kunstmuseum Basel

October 22, 2022–February 19, 2023,

https://kumu.picturepark.com/s/HN2WJ8Uh

The Kunstmuseum Basel’s classic modernism division boasts one of the most prestigious collections of its kind. Yet the work of assembling it was begun at a comparatively late date. In the summer of 1939, the Kunstmuseum acquired twenty-one outstanding works of German and French modernism. Denounced as “degenerate,” they had been forcibly removed from German museums in 1937 in pursuance of Nazi cultural policy, then categorized as “internationally salable” and sold through the art market. The exhibition Castaway Modernism at the Kunstmuseum Basel | Neubau sheds light on the various aspects of this turning point in the history of the Basel collection. It interweaves the widely told and popular story of how these treasures were saved with a closer look at the contemporary debates within society over a business transaction with a dictatorial regime. The works purchased in 1939 are shown in their historic context, appearing side by side with other major works of German Expressionism from museums and private collections all over the world.

Another key section of the presentation investigates the fates of works that feature in the history of the Basel acquisitions yet are now considered destroyed or missing. The Kunstmuseum Basel directly purchased more objects from the stockpile confiscated from German museums than any other institution. The Musée des Beaux-Arts in Liège was the only other museum to acquire a significant set of artifacts formerly held by German museums, buying nine works. The purchases reflected a seminal decision to build a modern collection and mark the moment the Kunstmuseum Basel opened its doors to the art of the time.

Historical background:

Germany Since the turn of the century, many German museums had spent considerable sums on collections of modern art, buying works of Expressionism, the New Objectivity, Cubism, and Dadaism as well as French modernism. The National Socialists, who had seized power in 1933, branded such art with the derogatory label “degenerate.” In the summer of 1937, the Nazi authorities seized more than 21,000 works of “degenerate” art from German museums. Works by Jewish artists and works with Jewish or political subjects were among the primary targets of the campaign. Many of the confiscated works were displayed in the exhibition Degenerate Art held in Munich in 1937.

Out of the vast stockpile, around 780 paintings and sculptures and 3,500 works on paper were declared “internationally salable”—which is to say, they were seen as suitable for sale abroad to raise funds in foreign currencies. These works were moved to a storage site in the north of Berlin. 125 works were selected for an auction to be held by Theodor Fischer in Lucerne in late June 1939. Four art dealers, among them Karl Buchholz and Hildebrand Gurlitt, were brought on board to find international buyers for the remaining art. Much of the “unsalable” stockpile was burned in Berlin on March 20, 1939.

Basel around 1939

In 1936, the Kunstmuseum Basel had inaugurated its new home on St. Alban-Graben— today’s Hauptbau. The relocation into the spacious building revealed how little the collection of modern paintings had to offer: the works of Old Masters Konrad Witz and Hans Holbein the Younger constituted the core of the holdings. Otto Fischer, the museum’s director at the time, had sought to rectify this imbalance, but several attempts to buy modern art had been rebuffed.

Taking the helm of the museum in 1939, Georg Schmidt, like his predecessor, wanted to build a modern collection. As a journalist, he had observed and criticized the persecution of modern art in Germany since 1933. His ambition was to buy as many of the confiscated works as possible—at the upcoming auction in Lucerne, but also directly from the warehouse in Berlin, which he visited in late May 1939 at the invitation of the dealers Buchholz and Gurlitt, who had been tasked with “liquidating” the art. Buchholz and Schmidt drew up a selection of works that was sent to Basel for inspection.

The Fischer auction in Lucerne

The auction Modern Masters from German Museums was held at Galerie Theodor Fischer, Lucerne, on June 30, 1939. The Kunstmuseum’s board of trustees applied to the Canton of Basel-City for a special fund in the amount of CHF 100,000 for acquisitions of art formerly held by German museums. The question of whether buying art from a dictatorial regime was a defensible decision—especially at a time when everything suggested that war was imminent—was controversial. On the evening before the auction, however, the canton allocated CHF 50,000. At the auction, the Kunstmuseum purchased eight works: Paul Klee’s Villa R, a still life by Lovis Corinth, Otto Dix’s Portrait of the Artist’s Parents I, Paula Modersohn-Becker’s Self-Portrait as a Half-Length Nude with Amber Necklace II, and Franz Marc’s Two Cats, Blue and Yellow, as well as André Derain’s Still Life with Calvary, a work on paper by Marc Chagall, and his large painting The Pinch of Snuff (Rabbi). These works now rank among the highlights in the museum’s classic modernism galleries.

Even before the auction, Marc’s Animal Destinies was the first work removed from a German museum to be bought directly from Berlin. Two weeks after the Lucerne auction, the works sent from Berlin for inspection were set up in the Kunstmuseum’s skylight hall. The museum purchased an additional twelve of them, including Max Beckmann’s The Nizza in Frankfurt am Main, Lovis Corinth’s Ecce Homo, two paintings by Modersohn-Becker, and Oskar Kokoschka’s Bride of the Wind, a masterwork of Expressionism. Due to budgetary constraints, the museum was unable to buy all works at the auction and from the selection sent to Basel that Schmidt would have liked to acquire.

The exhibition Castaway Modernism is the first to reunite the works of “degenerate” art that entered the museum’s collection at the time with those that Basel did not purchase, among them Pablo Picasso’s The Soler Family, James Ensor’s Death and Masks, and Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s Seated Girl. Three of the works that traveled to Basel for inspection in 1939 or that Schmidt had requested are now believed to have been destroyed: Oskar Schlemmer’s Three Women and Otto Dix’s The Widow and Trench. Represented by black-and-white projections, these works are included in the exhibition as well.

The “forgotten generation”

The great majority of the 21,000 confiscated artifacts were works by artists in the early stages of their careers. Many of these objects were destroyed in 1938 because the Nazis did not see any possible use for them. The names of the creators faded into obscurity. The exhibition Castaway Modernism dedicates a separate gallery to this “forgotten generation.” Marg Moll’s Dancer is an especially striking illustration of the vagaries of the history of loss bound up with the persecution of “degenerate art”: until recently, the work, which was displayed in the exhibition Degenerate Art, was thought to have been destroyed. In 2010, it was recovered during the construction of a new subway line from the rubble left by the bombing of Berlin. Films in the exhibition Silent films with a running time of around three minutes based on historic photographs and documents play in a loop in each gallery and serve as an introduction to the exhibits. The films were developed and produced by teamstratenwerth.

The scholarly catalogue reconstructs the events, beginning with the confiscations from German museums, and embeds them in their historical context. Essays on the auction in Lucerne, on Georg Schmidt’s strategy, and on the place of the acquisitions in the history of the Basel collection bring specifically Swiss aspects into focus. With essays by Claudia Blank, Gregory Desauvage, Uwe Fleckner, Meike Hoffmann, Georg Kreis, Eva Reifert, Tessa Rosebrock, Ines Rotermund-Reynard, Sandra Sykora, Christoph Zuschlag. Eds. Eva Reifert, Tessa Rosebrock, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 296 pages, 200 illustrations, ISBN 978-3-7757-5221-3

Images

Pablo Picasso, The family Soler, 1903. Oil on canvas, 150 x 200 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Liège, © Succession Picasso / 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich.

Franz Marc Animal Destinies (The Trees Showed Their Rings, the Animals Their Veins), 1913 Oil on canvas, 194.7 x 263.5 cm Kunstmuseum Basel Photo: Jonas Hänggi | Kunstmuseum Basel Photo: Jonas Hänggi | |

| Oskar Kokoschka The Bride of the Wind, 1913 Oil on canvas, 180.4 x 220.2 cm Kunstmuseum Basel © Fondation Oskar Kokoschka / 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich Photo: Jonas Hänggi | Kunstmuseum Basel © Fondation Oskar Kokoschka / 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich Photo: Jonas Hänggi |

Marc Chagall The Pinch of Snuff (Rabbi), 1923-1926 Oil on canvas, 116.7 x 89.2 cm Kunstmuseum Basel © 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich Photo: Martin P. Bühler | Kunstmuseum Basel © 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich Photo: Martin P. Bühler | |

Paula Modersohn-Becker Self-Portrait as a Half-Length Nude with Amber Necklace II, 1906 Oil on canvas, 61.1 x 50 cm Kunstmuseum Basel Photo: Martin P. Bühler | Kunstmuseum Basel Photo: Martin P. Bühler |

Works sold as "internationally marketable"

| |||||

| Musée des Beaux-Arts de Liège | ||||

James Ensor Death and Masks, 1897 Oil on canvas, 78,5 x 100 cm | Musée des Beaux-Arts de Liège | ||||

Max Beckmann Descent from the Cross, 1917 Oil on canvas, 151 x 129 cm | |||||

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Peasants Eating Lunch (Peasant Meal), 1920 Oil on canvas, 133 x 166 cm |

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Peasants Eating Lunch (Peasant Meal), 1920 Oil on canvas, 133 x 166 cm | Ulmberg Collection |

Barnes Foundation

October 16, 2022–January 29, 2023

This fall, in celebration of its centennial, the Barnes Foundation will present Modigliani Up Close, a major loan exhibition that shares new insights into Amedeo Modigliani’s working methods and materials. On view in the Roberts Gallery from October 16, 2022, through January 29, 2023, Modigliani Up Close is curated by an international team of art historians and conservators: Barbara Buckley, Senior Director of Conservation and Chief Conservator of Paintings at the Barnes; Simonetta Fraquelli, independent curator and Consulting Curator for the Barnes; Nancy Ireson, Deputy Director for Collections and Exhibitions & Gund Family Chief Curator at the Barnes; and Annette King, Paintings Conservator at Tate, London.

Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) is among the most celebrated artists of the 20th century. While many exhibitions have endeavored to reunite his paintings, sculptures, and drawings, Modigliani Up Close offers a unique opportunity to examine their production and explore how Modigliani constructed and composed his signature works. Featuring new scholarship that builds on research that began in 2017 with the major Modigliani retrospective at Tate Modern, this single-venue exhibition and its accompanying catalogue are the culmination of years of research by conservators and curators across Europe and the Americas. Modigliani Up Close furthers understanding of Modigliani’s approach to his art, refines a chronology of his paintings and sculptures, and helps to establish the locations and circumstances of where he worked.

“We are pleased to present this major exhibition that offers a detailed investigation of Modigliani’s unique style,” says Thom Collins, Neubauer Family Executive Director and President. “Stemming from a multiyear, global research effort, the show has brought the international art community together to create a collaborative vision of the artist’s practice, leaving a lasting legacy for future Modigliani scholarship. The Barnes collection is home to 16 works by the artist, one of the largest and most important groups of the artist’s works in the world, and the project provided a unique opportunity to fully explore their significance. We see once more how Dr. Barnes broke new ground in the history of collecting modern art.”

Featuring nearly 50 works from major collections, and organized into thematic sections, the exhibition presents paintings and sculptures alongside new findings that have resulted from the technical research of collaborating conservators, conservation scientists, and curators. Using analytical techniques, including X-radiography, infrared reflectography, and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), conservators and conservation scientists reveal previously unknown aspects of Modigliani’s work. Visitors will feel closer to Modigliani as an artist, seeing his work through the eyes of the experts, catching glimpses of the artist’s hand hidden beneath the surfaces of his work.

“Thanks to the work of conservators and curators from museums around the globe, Modigliani Up Close offers an unrivaled opportunity to understand how the artist made his iconic paintings and sculptures,” says Nancy Ireson. “The exhibition is a perfect demonstration of how, in addition to producing innovative research, the Barnes Foundation brings together colleagues in the field to share their findings and thoughts.”

This exhibition holds a special significance at the Barnes, as Dr. Albert C. Barnes was one of Modigliani’s earliest collectors in the United States and helped shape the artist’s critical reception in this country. In addition to works on paper, there are 12 significant paintings and one carved stone sculpture by Modigliani in the Barnes collection. With 12 paintings each, the Barnes and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, have the largest collections of Modigliani paintings in the world.

To learn more about works in Modigliani Up Close, visitors can use Barnes Focus, a mobile guide that works on any smartphone with a web browser. Previously only accessible for works in the Barnes collection, Modigliani Up Close marks the first occasion Barnes Focus can be used to explore loaned works in an exhibition. To use it, visitors simply open the guide by navigating to barnesfoc.us on a mobile browser and focus on a work of art; the guide will recognize the work and deliver information about it. Barnes Focus also leverages the Google Translate API, so you can automatically translate the guide into a variety of languages.

CATALOGUE

The fully illustrated exhibition catalogue, Modigliani Up Close, is published by the Barnes Foundation in association with Yale University Press and edited by Barbara Buckley, Simonetta Fraquelli, Nancy Ireson, and Annette King. The catalogue, featuring 360 images, offers a focused exploration of how Modigliani constructed and composed his signature works and sheds light on Dr. Barnes’s role in the trajectory of Modigliani’s career. The Barnes collection is home to one of the most important groups of Modigliani works in the world and the catalogue brings these works together with some 50 other important examples from public and private collections around the world.

Organized into thematic groupings, the works are interpreted through the lens of new research carried out by renowned conservators, including Barbara Buckley and Annette King. In addition to scholarly contributions by the curatorial team, the book includes essays by Cindy Kang, Associate Curator at the Barnes, and art historian Alessandro De Stefani, and scholarly entries co-written by the project’s collaborating conservators, curators, and conservation scientists from participating institutions such as Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Ohio; Art Institute of Chicago; the Barnes Foundation; Collezione Fondazione Francesco Federico Cerruti per l’Arte; Dallas Museum of Art; Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC; Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Kunstmuseum Bern; LaM – Lille Métropole Musée d’Art Moderne, d’Art Contemporain et d’Art Brut, Villeneuve d’Ascq, France; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Minneapolis Institute of Art; Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen; Musée National Picasso–Paris; Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Reuben and Edith Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, Israel; Saint Louis Art Museum; Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Images

Amedeo Modigliani. Young Woman in a Yellow Dress (Renée Modot), 1918. Collezione Fondazione Francesco Federico Cerruti per l’Arte, on long-term loan to the Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Turin

Cerruti Foundation for Art, on long term loan to Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art, Turin

Amedeo Modigliani. Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater, 1918–19. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, by gift, 37.533

Photo credit: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation / Art Resource, NY

Amedeo Modigliani. Nude with a Hat (recto), 1908. Reuben and Edith Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, Israel. Hecht Museum, Haifa

Photograph © Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, Photo: Shay Levy

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Maud Abrantes (verso), 1908. Reuben and Edith Hecht Museum, University of Haifa

Photograph © Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, Photo: Shay Levy

Amedeo Modigliani, Jeanne Hébuterne, 1919. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Nate B. Spingold, 1956 (56.184.2)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource

Amedeo Modigliani. Black Hair (Young Dark-Haired Girl), 1918. Musée National Picasso–Paris. Gift of Pablo

Picasso, 1978

© RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY Photo: Adrien Didierjean.

Amedeo Modigliani. Self Portrait, 1919. Museu de Arte Contemporanea da Universidade de São Paulo, Gift of Yolanda Penteado and Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho

1963.2.16 / MAC USP Collection [Museu de Arte Contemporânea da USP Collection, São Paulo, Brazil

MAC USP Collection [Museu de Arte Contemporânea da USP Collection, São Paulo, Brazil]

Amedeo Modigliani. The Young Apprentice, 1918-19.

Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris, Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume Collection RF 1963-7

© RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY Photo: Hervé Lewandowski.

Details of hand and finger showing partly overpainted wedding band

Amedeo Modigliani. Portrait of the Red-Headed Woman (Portrait de la femme rousse), 1918. BF206

Image © The Barnes Foundation

National Gallery of Art,

November 20, 2022–February 12, 2023

March 18, 2023–June 18, 2023

A leading figure in the art of Renaissance Venice, Vittore Carpaccio (c. 1460/1466–1525/1526) is best known for his large, spectacular narrative paintings that brought sacred history to life. Celebrated in his native city of Venice for centuries, beloved for his observant eye, fertile imagination, and storytelling prowess, Carpaccio remains little known in the U.S.—except as a namesake culinary dish, "Steak Carpaccio.”

Vittore Carpaccio: Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice is set to establish the artist’s reputation among American visitors with this, his first retrospective ever held outside Italy. The exhibition will be on view at the National Gallery of Art from November 20, 2022, through February 12, 2023. Some 45 paintings and 30 drawings will include large-scale canvases painted for Venice’s charitable societies and churches alongside smaller works that decorated the homes of prosperous Venetians. The exhibition is organized by the National Gallery and Musei Civici di Venezia, also the organizers of the 2019 exhibition Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice.

“The National Gallery of Art is pleased to partner, once again, with the Musei Civici di Venezia, this time to introduce American audiences to a lesser-known protagonist of the Venetian Renaissance, Vittore Carpaccio,” said Kaywin Feldman, director, National Gallery of Art. “Our visitors will be delighted by Carpaccio’s vivid and dynamic paintings that bring to life Venice in the 15th and 16th centuries. Through his masterful storytelling, Carpaccio illustrated the maritime empire during a fascinating period when it was a cultural crossroads between West and East. We are grateful to the many museums, churches, and collectors who have generously lent their works to share with the public in this historic exhibition.”

Several paintings have been newly conserved for the exhibition. Two of Carpaccio’s best-known canvases from the Scuola degli Schiavoni were treated with the support of Save Venice, the organization dedicated to the preservation of the city’s cultural heritage: Saint Augustine in His Study (shortly after 1502)and Saint George and the Dragon (c. 1504–1507). Other treatments uncover discoveries about the original compositions. National Gallery conservator Joanna Dunn’s treatment of the museum’s Virgin Reading (c. 1505) reveals a baby Jesus previously hidden beneath a later repainting that sought to disguise where the painting had been cut down centuries ago.

The two paintings from the Scuola degli Schiavoni are among several works never before exhibited outside Italy, including the full, six-painting narrative cycle, Life of the Virgin (c. 1502–1508) made for the Scuola di Santa Maria degli Albanesi. The exhibition also includes the reunification of Fishing and Fowling on the Lagoon (c. 1492/1494)from the J. Paul Getty Museum and Two Women on a Balcony (c. 1492/1494) from Venice’s Museo Correr—two paintings that likely adorned a folding door.

Exhibition Curators

The exhibition is curated by Peter Humfrey, internationally recognized scholar of 15th- and 16th-century Venetian painting and Professor Emeritus of art history at the University of St Andrews, Scotland, in collaboration with Andrea Bellieni, curator at the Musei Civici di Venezia, and Gretchen Hirschauer, curator of Italian and Spanish painting at the National Gallery of Art.

Exhibition Overview

Vittore Carpaccio: Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice begins in the West Building’s West Garden Court with a special installation of Fishing and Fowling on the Lagoon (c. 1492/1494)and Two Women on a Balcony (c. 1492/1494). The two compositions were painted on the same panel of wood but were likely cut in half in the 1700s. When seen together, the paintings tell the story of two women sitting on a balcony while their husbands enjoy a day of sport on the Venetian lagoon. The panels are believed to have decorated folding doors that led into a domestic space in a Venetian palace. Here, they lead visitors into the exhibition.

The exhibition continues with an emphasis on Carpaccio’s innovations in Venetian painting. Early examples of private devotional paintings by the artist include Virgin and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist (c. 1493–1496) from Germany’s Städel Museum, a unique depiction of the Virgin and Child as aristocratic Venetians of the 15th century. Another highlight of the exhibition is the reunification of the complete cycle of six canvases depicting the life of the Virgin Mary made for the Scuola di Santa Maria degli Albanesi. Carpaccio sets the story in Venice of his own day, blending details of Venetian architecture, furniture, and clothing with elements that evoke Jerusalem. Carpaccio also transposed scenes from classical mythology to contemporary Venice in other works like Departure of Ceyx from Alcyone (c. 1498/1503) from the collection of The National Gallery, London.

The exhibition includes examples from the three extant narrative cycles that Carpaccio was commissioned to create. His final narrative cycle made for the Scuola di Santo Stefano is represented by Ordination of Saint Stephen (1511) from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. Among the largest works in the exhibition is the Lion of Saint Mark (1516) from the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Palazzo Ducale. Spanning more than twelve feet, the painting shows the traditional symbol of Venice, a winged lion. The lion stands half in the sea and half on land, alluding to the vast sea-faring empire.

Carpaccio pioneered narrative subjects in altarpieces. The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand Christians on Mount Ararat (1515) from the Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice, was created to decorate the altar of the Ottobon family in the church of Sant’Antonio di Castello, which no longer exists. Its original context can be seen in another painting, Vision of Prior Francesco Ottobon (c. 1513), from the Gallerie dell’Accademia.

More of Carpaccio’s drawings survive than those of any other Venetian painter of his generation. Outstanding works on their own, the drawings include rough sketches for paintings presented in the exhibition, along with meticulous preparatory drawings for paintings too large to travel for this show. Preparatory drawings for a narrative cycle of the Life of Saint Ursula for the Scuola di Sant’Orsola, the artist’s first major commission, include a remarkable double-sided drawing Head of a Young Woman in Profile/Head of a Young Woman in Three-Quarter View (c. 1488–1489) from the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Finally, an interpretive and reading room features View of Venice (1500), a remarkable woodcut by Jacopo de’ Barbari. Drawn from the National Gallery’s collection, the six-sheet print details Venice as it appeared in Carpaccio’s day and shows the thousands of buildings, squares, canals, bridges, gardens, and sculptures that filled the bustling city-state.

Exhibition Catalog

Copublished by the National Gallery of Art and Yale University Press, this 340-page illustrated catalog features essays by curators Peter Humfrey and Andrea Bellini along with contributions by other leading scholars exploring the full range of Carpaccio’s artistry and presenting new research on the extraordinary artist.

Sara Menato of the Fondo Ambiente Italia analyzes extensively Carpaccio’s drawings. Susannah Rutherglen, independent scholar and former exhibitions research assistant at the National Gallery of Art, illuminates Carpaccio’s narrative paintings for the Venetian confraternities known as scuole. Professor Deborah Howard, St. John’s College, Cambridge, explores the artist’s rendering of architecture. Professor Catherine Whistler of the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford, offers her insights on Carpaccio as draftsman. Joanna Dunn, conservator at the National Gallery of Art, reveals elements of the artist’s pictorial technique. Professor Linda Borean, Department of Humanities and Cultural Patrimony, University of Udine, Italy, offers a historical perspective on early collectors and critics of Carpaccio. Andrea Bellieni of the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia shares his insights on the modern understanding of Carpaccio that began in the 19th century.

Vittore Carpaccio

Two Women on a Balcony, c. 1492/1494

oil on panel

overall: 94.5 x 63.5 cm (37 3/16 x 25 in.)

Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Museo Correr, Venice

Vittore Carpaccio

Meditation on the Passion of Christ, c. 1494-1496

oil on panel

overall: 66.5 x 84.5 cm (26 3/16 x 33 1/4 in.)

framed: 87.9 x 105.7 x 7.6 cm (34 5/8 x 41 5/8 x 3 in.)

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1911 (11.118)