This autumn, 9 October – 12 January 2014, the National Gallery presents the UK’s first major exhibition devoted to the portrait in Vienna - Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900.

Portraiture is closely identified with the distinctive flourishing of modern art in the Austrian capital during its famed fin-de-siècle: artists worked to the demands of patrons, and in Vienna modern artists were compelled to focus on the image of the individual.

Iconic portraits from this time – by Gustav Klimt , Egon Schiele, Richard Gerstl, Oskar Kokoschka and Arnold Schönberg are displayed alongside works by important yet less widely known artists such as Broncia Koller and Isidor Kaufmann.

In contrast to their contemporaries working in Paris, Berlin and Munich, and in response to the demands of their local market, Viennese artists such as Klimt remained focused on the image of the individual. Portraits therefore dominate their production, enabling this exhibition to reconstruct the shifting identities of artists, patrons, families, friends, intellectual allies and society celebrities of this time and place.

Paintings from major collections on both sides of the Atlantic, including those that hardly ever leave the walls of the Belvedere in Vienna and MoMA in New York are shown next to rarely seen, yet remarkable images from smaller public and private collections. Most works are on canvas, though visitors will also see drawings and the haunting death masks of Gustav Klimt (1918); Ludwig van Beethoven (1827), Egon Schiele (1918) and Gustav Mahler (1911), all on loan from the Wien Museum Karlsplatz. A family photograph album belonging to Edmund de Waal, acclaimed author of 'The Hare with Amber Eyes' (2010) will also be exhibited. De Waal’s family were once a very wealthy European Jewish banking dynasty centered in Vienna; this photograph memoir has been described as an ‘enchanting history lesson’.

Highlight paintings include:

'The Family (Self Portrait)' by Schiele (1918, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna)

'Nude Self Portrait by Gerstl' (1908, Leopold Museum, Vienna)

'Portrait of a Lady in Black' by Gustav Klimt (about 1894, Private collection)

Also on show is

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Hermine Gallia (1904, The National Gallery, London)

the haunting image of a Jewish patron of art and design whose family would be driven from Vienna by anti-Semitism in the 1930s. It is the only painting by this seminal Viennese artist in the National Gallery’s collection.

The exhibition also features a room devoted to the portrait as a declaration of love and commemoration of the dead while a final display looks at unfinished or abandoned works that failed to meet the expectations of artists or patrons.

'Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900' explores an extraordinary period of the multi-national, multi-ethnic, multi-faith city of Vienna as imperial capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1867–1918). The exhibition looks back at middle-class Vienna in the early 19th century, the so-called Biedermeier period, as represented by artists like Frederich von Amerling and Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, whose portraits were ‘rediscovered’ by the city’s modern artists in 1900. It then moves to the 1867 – 1918 period to consider images of children and families, of artists, and of men and women in their professional and marital roles.

The period began with liberal and democratic reform, urban and economic renewal, and religious and ethnic tolerance, but ended with the rise of conservative, nationalist and anti-Semitic mass movements. Such dramatic changes had a profound impact on the composition and confidence of Vienna’s middle classes, many of them immigrants with Jewish roots or connections. Portraits were the means by which this sector of society - the ‘New Viennese’ - declared its status and sense of belonging; portraits also increasingly served to express their anxiety and alienation.

'Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900' is curated by Dr. Gemma Blackshaw, Associate Professor, History of Art and Visual Culture at Plymouth University and guest curator at the National Gallery. The project was conceived by Christopher Riopelle, Curator of Post-1800 Paintings at the National Gallery.

'Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900' is organised by the National Gallery, London.

From a fascinating review:

.

Egon Schiele’s Erich Lederer, 1912, the pose as elegantly Dyckian as any Stuart fop

This is an exhibition that from beginning to end loses its way. The year 1900 is its proposed focus, yet it roams far back to the age of Schubert and bogs down in an examination of the middle classes of his day, with the clutter of Biedermeier furniture, the clank and clunk of the German fortepiano and the whiff of tobacco in a Meerschaum pipe, and then offers, in only 73 exhibits, a threadbare patchwork history of Viennese portraiture from 1827 to 1918. Even with so little to show, the exhibition is diminished rather than enhanced by diversions into the Viennese fascination with death — so many of its citizens had taken to the Danube, the razor, the revolver and the rope that the city was known as “the suicide zone of Europe” (and what has that to do with portraiture?) — into women artists of the day (have we not had enough of gender politics in art?), and into “Imaging the Jew” — this last illustrated by one of the most beautiful portraits in the exhibition,

Isidor Kaufmann’s Young Rabbi of 1910.

The exhibition is far from being “a portrait of Vienna itself”, as Nicholas Penny puts it in his Director’s Foreword; it could hardly be that without some focus on the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte (craft workshops) — though some trifle by Kolomon Moser appears on the shelf behind Maria in Auchentaller’s portrait of 1912.

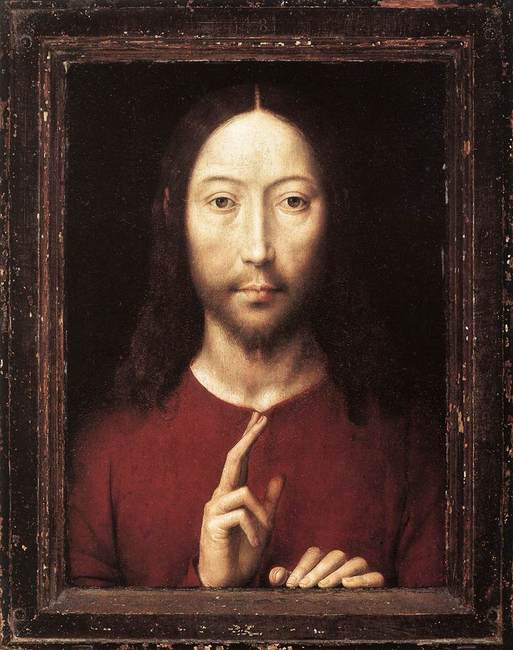

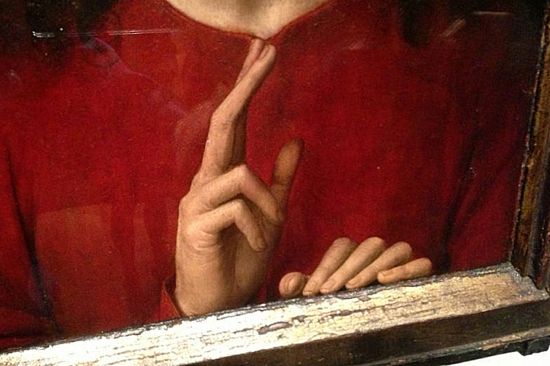

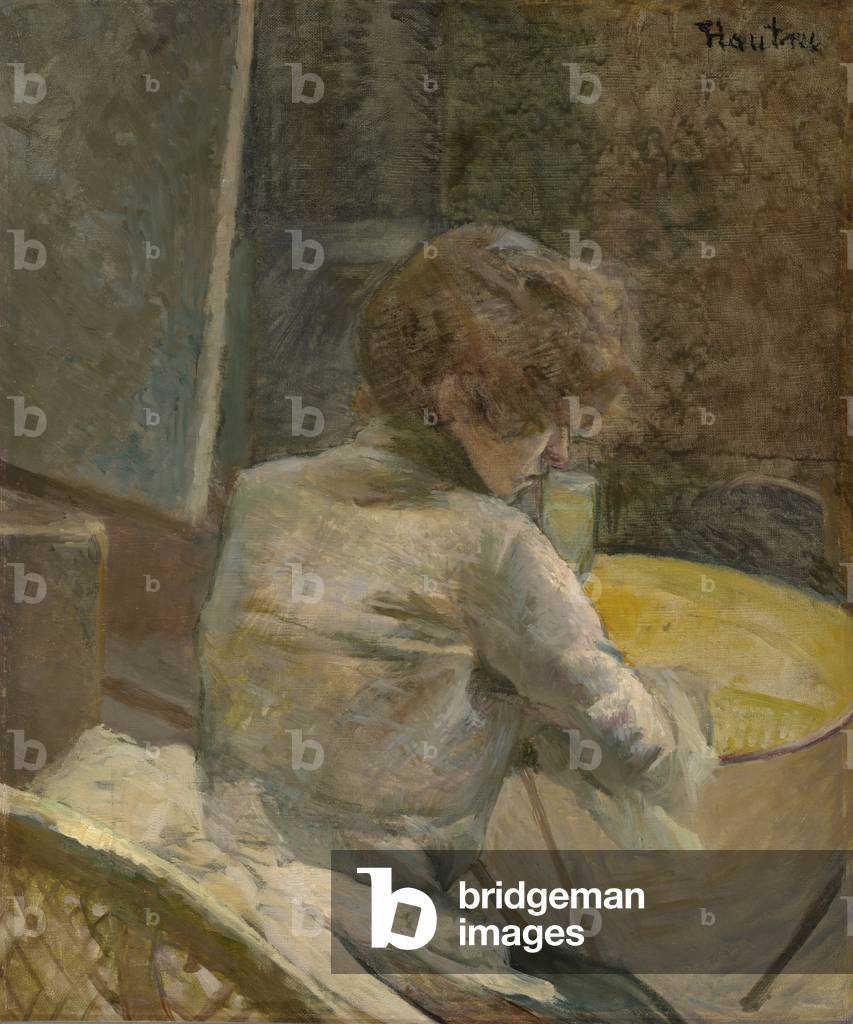

The exhibition comes to life with Klimt, aged 38 in 1900. We see an earlier Klimt, his Lady in Black of c.1894,(above) a thing of startling light, clarity, tone and silhouette, every detail of textile, stitching and jewellery, of ear, hair, eye, lips, double chin and hand caught to perfection in and against the light, every aspect of its brilliance quite astonishing. Ten years on we encounter Hermine Gallia of 1904, (above) a portly Jewess dissolving in a Whistlerian drift of faintly coloured tone, anchored in pattern but all other details suggested, not defined. In it we can nevertheless see roots of the highly coloured, ornately detailed tricks and mannerisms that were, within a decade, to make Klimt’s work so utterly seductive —

his posthumous (and unfinished, for he too died) portrait of the dancer Ria Munk of 1917-18, makes the point.

From another excellent review:

Schiele Egon Schiele's Portrait of Albert Paris von Gütersloh, 1918 Photograph: Schiele/Minneapolis Institute of Arts

The stars of the show are undoubtedly Schiele and Klimt. Schiele's portraits, especially those of himself, are a bit frightening and grotesque, and deliberately, provocatively so. I am immune to Schiele. Klimt, who began as an extremely proficient and conventional portraitist, did at least develop in interesting ways, and wasn't just bludgeoning us with his ego. There was a sense of inquiry in his work, even at its most decorative, an interest in form and surface that at its best becomes almost oceanic.

Gustav Klimt's portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl, 1917-18. Photograph: National Gallery

Perhaps the real ending to the show comes not among the death masks or the portrait of Emperor Franz Joseph, lain out for the undertaker, but in Klimt's 1917-18 portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl, which hangs alone on a dark wall. Klimt died before finishing the painting. It seems complete without his usual decorative excess. I am held by the painting's symmetry, the way that Zuckerkandl looks directly at us. Apart from her head and bust, the rest is vagueness. Later, she was murdered in a Nazi concentration camp. Here, she still has something of a life to live, which makes this painting's incompleteness painful and expressive in ways the artist could never have intended or envisaged.

And from still another review (images added):

For example, if like me you’d always thought of Schiele’s or Kokoschka’s twisted and tormented portraits as visual manifestations of Freud’s writings about neurosis and hysteria, just take a look at the work of one of their predecessors, the surpassingly strange Anton Romako, who died in 1889. His pendant portraits of the newspaper man

Christoph Reisser and

his wife Isabella

are so unsettling that on first seeing them I found I’d inadvertently taken a step backwards. Husband and wife are seen from head on, as though caught in the beam of a headlamp. Dressed to the nines, Isabella smiles as she knows she must. But what a smile:self-conscious and tearful, she bares her white teeth as if she might bite us. Christoph, by contrast is a big powerful man who crumples that day’s newspaper in one hand. Assured, calm and self -confident, he could be a psychiatrist, she his patient.

Compare this to Kokoschka’s double portrait of the young art historian Hans Tietze and his wife Erica Tietze-Conrat of 1909, where the husband lowers his eyes and bites his lower lip hard enough to draw a drop of blood. If he is eaten up with anxiety his wife stares vacantly into space with the unfocused eyes of a person in shock.

And that portrait is mild stuff compared to Kokoschka’s dying Count Verona, where on the wall behind the tubercular sitter is a palm print made with the blood he has just coughed up and wiped from his mouth and chin.

Publication

'Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900' is published by National Gallery Company to accompany the exhibition. The foreword to the accompanying book, edited by Dr. Blackshaw, is written by Edmund de Waal.

_-_WGA14926.jpg/445px-Hans_Memling_-_St_John_and_Veronica_Diptych_(right_wing)_-_WGA14926.jpg)

,_Dancers_in_the_Classroom,_c._1880._Oil_on_canvas,_oil_39.4_x_88.4_cm._Sterling_and_Francine_Clark_Art_Institute.jpg)

,_from_Los_Caprichos_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/508px-Francisco_Jos%C3%A9_de_Goya_y_Lucientes_-_The_sleep_of_reason_produces_monsters_(No._43),_from_Los_Caprichos_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/800px-Francisco_Jos%C3%A9_de_Goya_y_Lucientes_-_Where_There's_a_Will_There's_a_Way_(A_way_of_Flying)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)