National TourSmithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. (February 27, 2009 – January 3, 2010)

Frick Art & Historical Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (January 30, 2010 – April 25, 2010)

Fort Wayne Museum of Art in Fort Wayne, Indiana (May 21, 2010 – August 22, 2010)

Whatcom Museum of History and Art in Bellingham, Washington (September 16, 2010 – January 9, 2011)

The Mennello Museum of American Art in Orlando, Florida (February 11, 2011 – May 1, 2011)

Oklahoma City Museum of Art in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (May 26, 2011 – August 21, 2011)

Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Montgomery, Alabama (September 24, 2011 – January 15, 2012)

Muskegon Museum of Art in Muskegon, Michigan (February 16, 2012 – May 6, 2012)

Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul, Minnesota (June 2, 2012 – September 22, 2012)

New York State Museum in Albany, New York (October 19, 2012 – January 20, 2013)

Chazen Museum of Art in Madison, Wisconsin (February 16, 2013 – April 28, 2013)

Figge Art Museum in Davenport, Iowa (September 28, 2013 – January 5, 2014)

Portland Museum of Art in Portland, Maine (Jan. 30, 2014 – May 11, 2014)

In 1934, Americans grappled with an economic situation that feels all too familiar today. Against the backdrop of the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's administration created the Public Works of Art Project—the first federal government program to support the arts nationally. Federal officials in the 1930s understood how essential art was to sustaining America's spirit. Artists from across the United States who participated in the program, which lasted only six months from mid-December 1933 to June 1934, were encouraged to depict "the American Scene." The Public Works of Art Project not only paid artists to embellish public buildings, but also provided them with a sense of pride in serving their country. They painted regional, recognizable subjects—ranging from portraits to cityscapes and images of city life to landscapes and depictions of rural life—that reminded the public of quintessential American values such as hard work, community and optimism.

1934: A New Deal for Artists was organized to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Public Works of Art Project by drawing on the Smithsonian American Art Museum's unparalleled collection of vibrant artworks created for the program. The paintings in this exhibition are a lasting visual record of America at a specific moment in time. George Gurney, curator emeritus, organized the exhibition with Ann Prentice Wagner, who is now the curator of drawings at the Arkansas Art Center.

The program was administered under the Treasury Department by art professionals in 16 different regions of the country. Artists from across the United States who participated in the program were encouraged to depict “the American Scene,” but they were allowed to interpret this idea freely. They painted regional, recognizable subjects—ranging from portraits to cityscapes and images of city life to landscapes and depictions of rural life—that reminded the public of quintessential American values such as hard work, community and optimism. These artworks, which were displayed in schools, libraries, post offices, museums and government buildings, vividly capture the realities and ideals of Depression-era America. “Artists were honored to be paid by the Public Works of Art Project for paintings that would be publicly displayed,” said Gurney. “The program also provided them with a sense of pride in serving their country.”

About the Public Works of Art Project

The United States was in crisis as 1934 approached. The national economy had fallen into an extended depression after the stock market crash of October 1929. Thousands of banks failed, wiping out the life savings of millions of families. Farmers battled drought, erosion and declining food prices. Businesses struggled or collapsed. A quarter of the work force was unemployed, while an equal number worked reduced hours. More and more people were homeless and hungry. Nearly 10,000 unemployed artists faced destitution. The nation looked expectantly to President Roosevelt, who was inaugurated in March 1933.

The new administration swiftly initiated a wide-ranging series of economic recovery programs called the New Deal. The President realized that Americans needed not only employment but also the inspiration art could provide. The Advisory Committee to the Treasury on Fine Arts organized the Public Works of Art Project Dec. 8, 1933. Within days, 16 regional committees were recruiting artists who eagerly set to work in all parts of the country. During the project’s brief existence, from December 1933 to June 1934, the Public Works of Art Project hired 3,749 artists who created 15,663 paintings, murals, sculptures, prints, drawings and craft objects at a cost of $1,312,000.

In April 1934, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., exhibited more than 500 works created as part of the Public Works of Art Project. Selected paintings from the Corcoran exhibition later traveled to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and other cities across the country. President Roosevelt, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and government officials who attended the exhibition in Washington acclaimed the art enthusiastically. The Roosevelts selected 32 paintings for display at the White House, including Sheets’ “Tenement Flats” (1933-34) and Strong’s “Golden Gate Bridge” (1934) (see each below). The success of the Public Works of Art Project paved the way for later New Deal art programs, including the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project.

Nearly 150 paintings from the Public Works of Art Project were transferred to the Smithsonian American Art Museum during the 1960s, along with a large number of artworks from subsequent programs that extended into the 1940s, especially the well-known Works Progress Administration program.

The exhibition is arranged into eight sections: “American People,” “City Life,” “Labor,” “Industry,” “Leisure,” “The City,” “The Country” and “Nature.” Works from 13 of the 16 regions established by the Advisory Committee to the Treasury on Fine Arts are represented in the exhibition.

The Public Works of Art Project employed artists from across the country including Ilya Bolotowsky, Lily Furedi and Max Arthur Cohn in New York City; Harry Gottlieb and Douglass Crockwell in upstate New York; Herman Maril in Maryland; Gale Stockwell in Missouri; E. Dewey Albinson in Minnesota; E. Martin Hennings in New Mexico; and Millard Sheets in California.

Several artists chose to depict American ingenuity.

(Note - all artworks - full credits below)

![]()

Ray Strong’s panoramic “Golden Gate Bridge” (1934)

pays homage to the engineering feats required to build the iconic San Francisco structure.

![]()

“Old Pennsylvania Farm in Winter” (1934) by Arthur E. Cederquist

features a prominent row of poles providing telephone service and possibly electricity, a rare modern amenity in rural America.

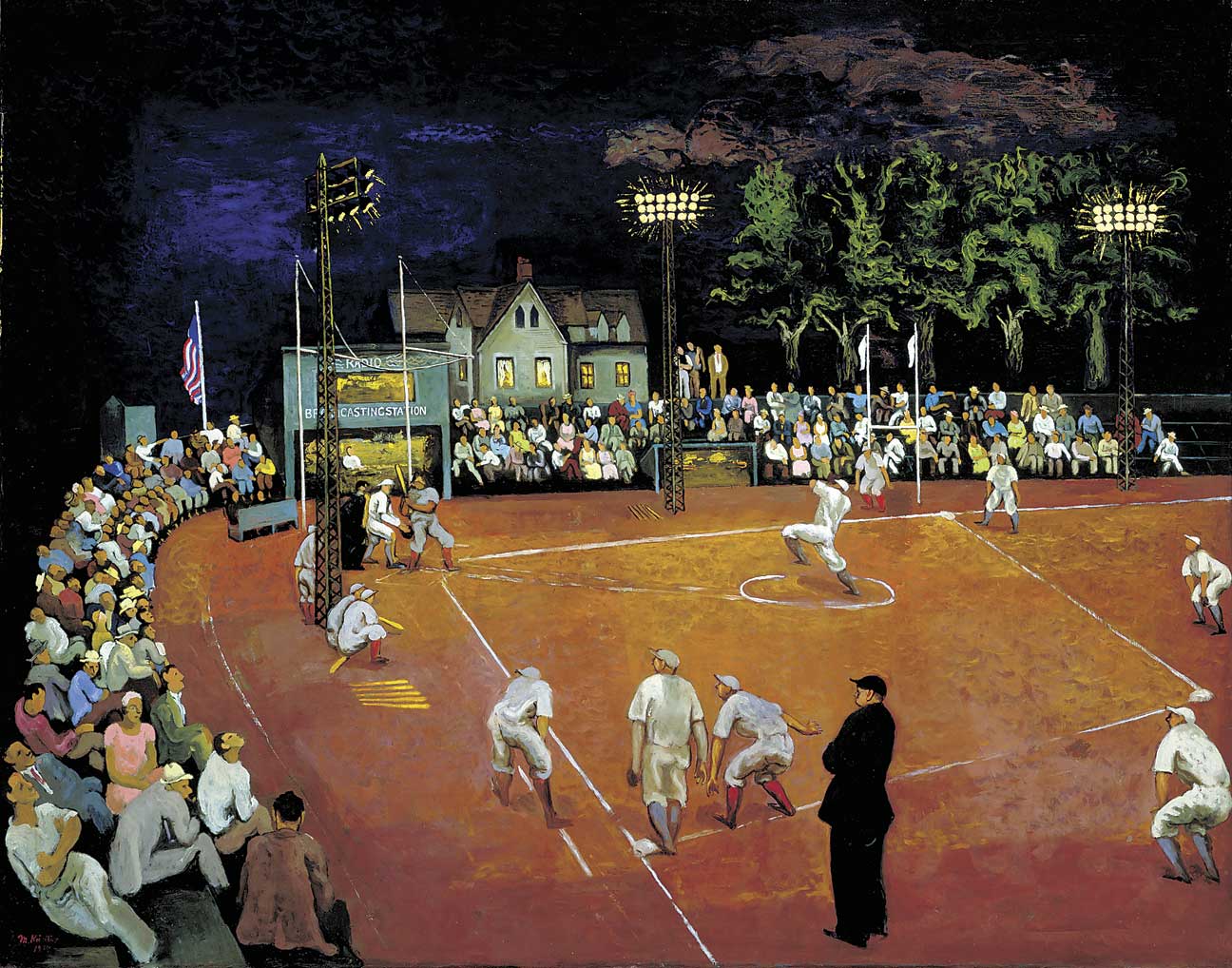

Stadium lighting was still rare when Morris Kantor painted

![]()

“Baseball at Night” (1934),

which depicts a game at the Clarkstown Country Club’s Sports Centre in West Nyack, N.Y.

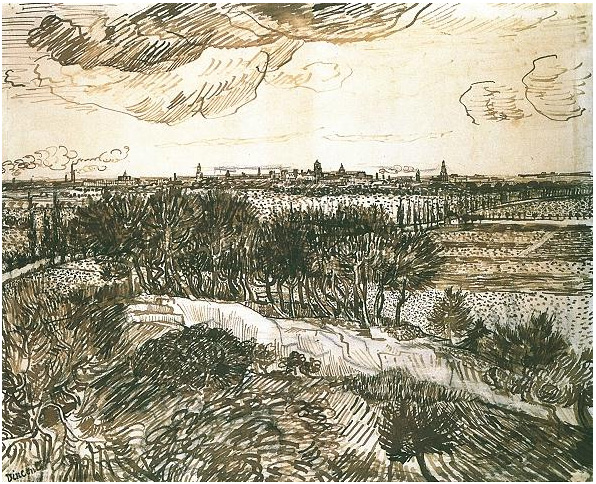

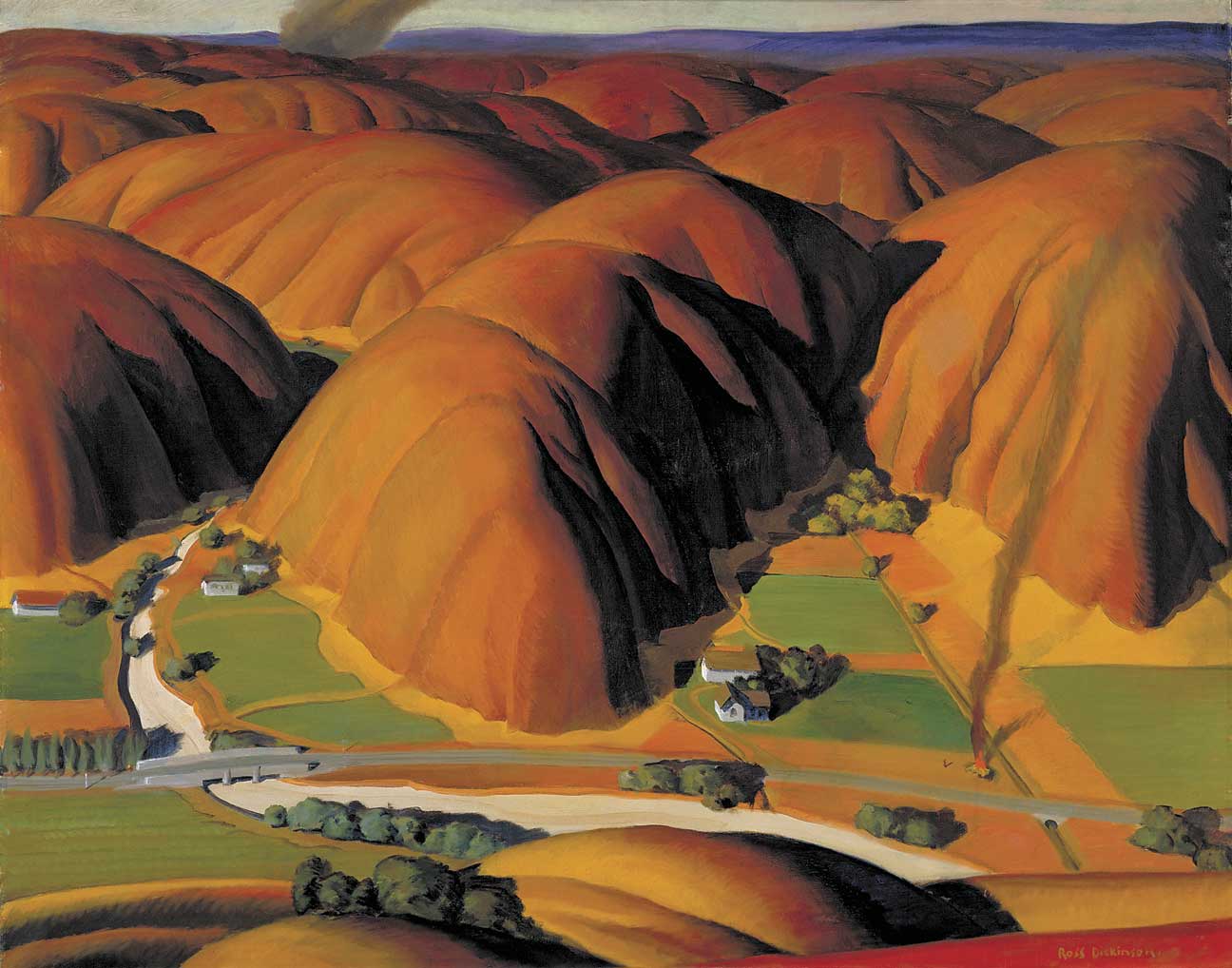

Ross Dickinson paints the confrontation between man and nature in his painting of southern California,

![]()

“Valley Farms” (1934).

He contrasts the verdant green, irrigated valley with the dry, reddish-brown hills, recalling the appeal of fertile California for many Midwestern farmers escaping the hopelessness of the Dust Bowl.

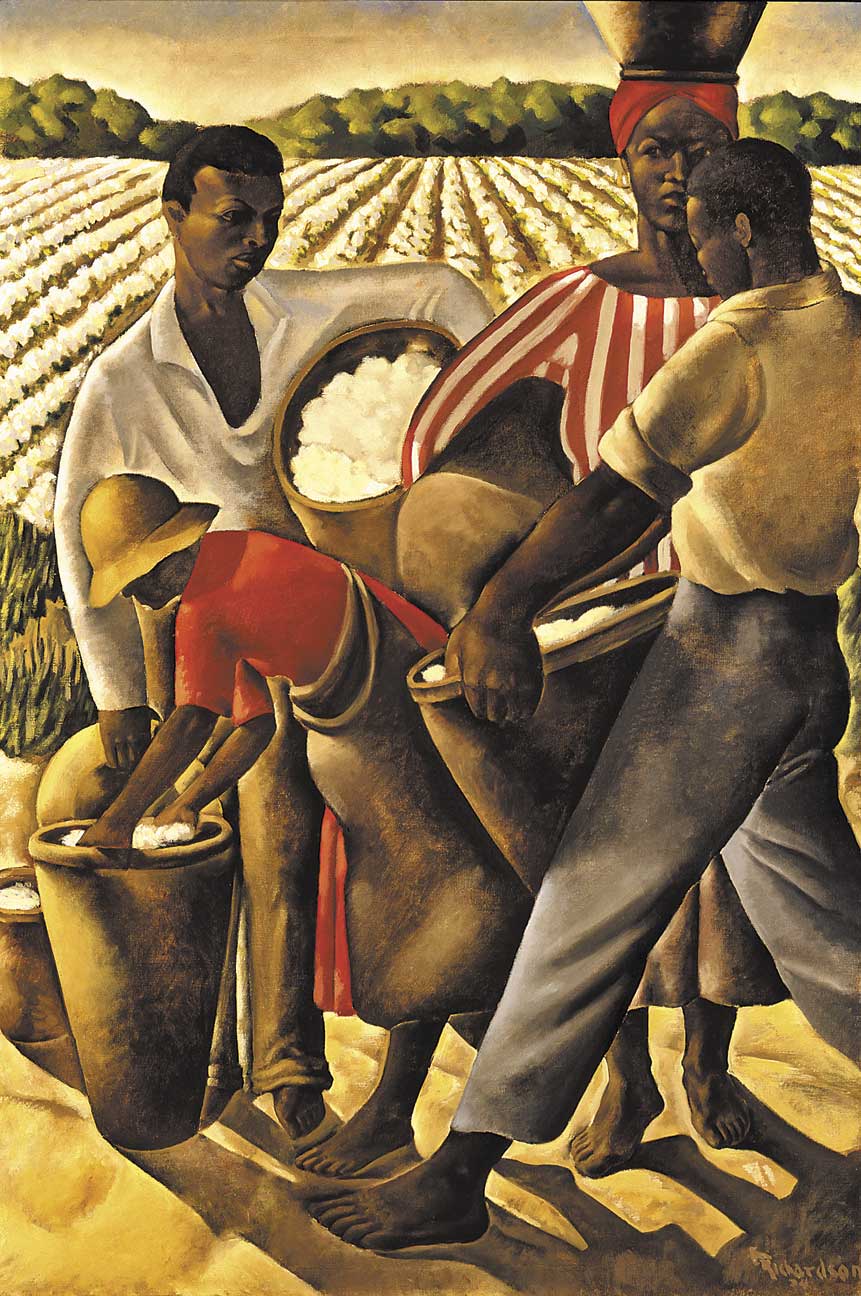

The program was open to artists who were denied other opportunities, such as African Americans and Asian Americans.

African American artists like Earle Richardson, who painted

![]()

“Employment of Negroes in Agriculture” (1934),

were welcomed, but only about 10 such artists were employed by the project. Richardson, who was a native New Yorker, chose to set his painting of quietly dignified workers in the South to make a broad statement about race.

In the Seattle area, where Kenjiro Nomura lived, many Japanese Americans made a living as farmers, but they were subject to laws that prevented foreigners from owning land and other prejudices. Nomura’s painting

![]() “The Farm”

“The Farm” (1934)

depicts a darker view of rural life with threatening clouds on the horizon.

From

a Washington Post review: (images added)

So why, if these paintings were supposed to make us feel better, are so many of them so depressing?

For one thing, I doubt whether it is -- or ever was -- the purpose of art to make people feel better. Some art certainly does that. And a bit of it is on view here.

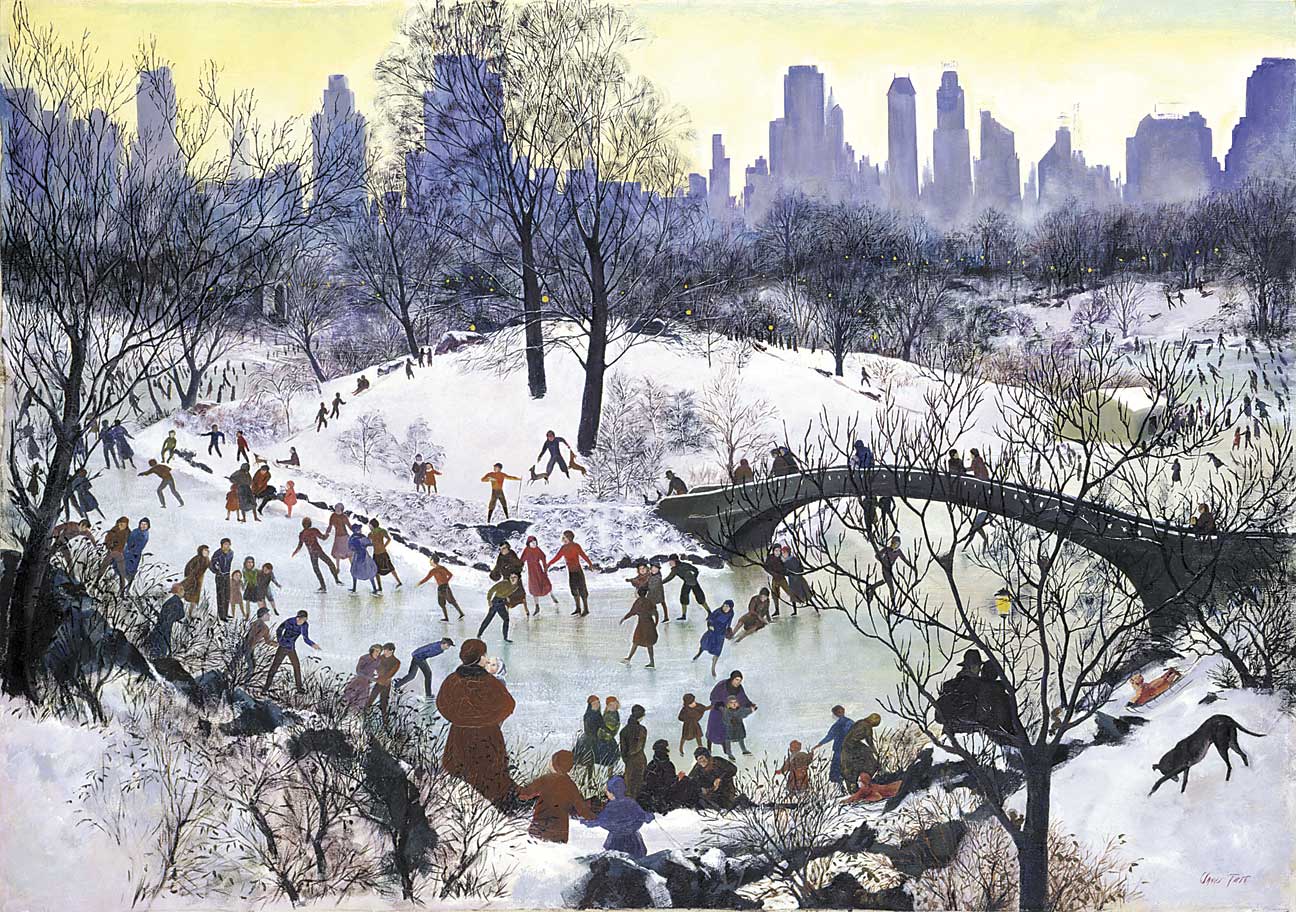

![]()

Agnes Tait's "Skating in Central Park"

is one such picture, depicting an almost Currier-and-Ives-style scene of outdoor recreation.

Ray Strong's "Golden Gate Bridge" (above)is another, in the way it celebrates the can-do spirit of those who designed and built the engineering marvel despite setbacks. (A storm on Halloween 1933 had washed away a trestle.)

Escapism is a popular theme. See

![]()

Paul Kirtland Mays's "Jungle,"

which is anything but American, or

![]()

Julia Eckel's jolly "Radio Broadcast,"

which drew attention to the popular diversion of live radio theater.

![]()

Erle Loran's chilly "Minnesota Highway" looks to a blue horizon.

But a far more common temper is that found in Kenjiro Nomura's "The Farm" (above)

![]()

or Robert A. Darrah Miller's "Farm,"

both of which feature barns sitting empty and dark, devoid of people and animals...

It's there in such obvious pictures as

![]()

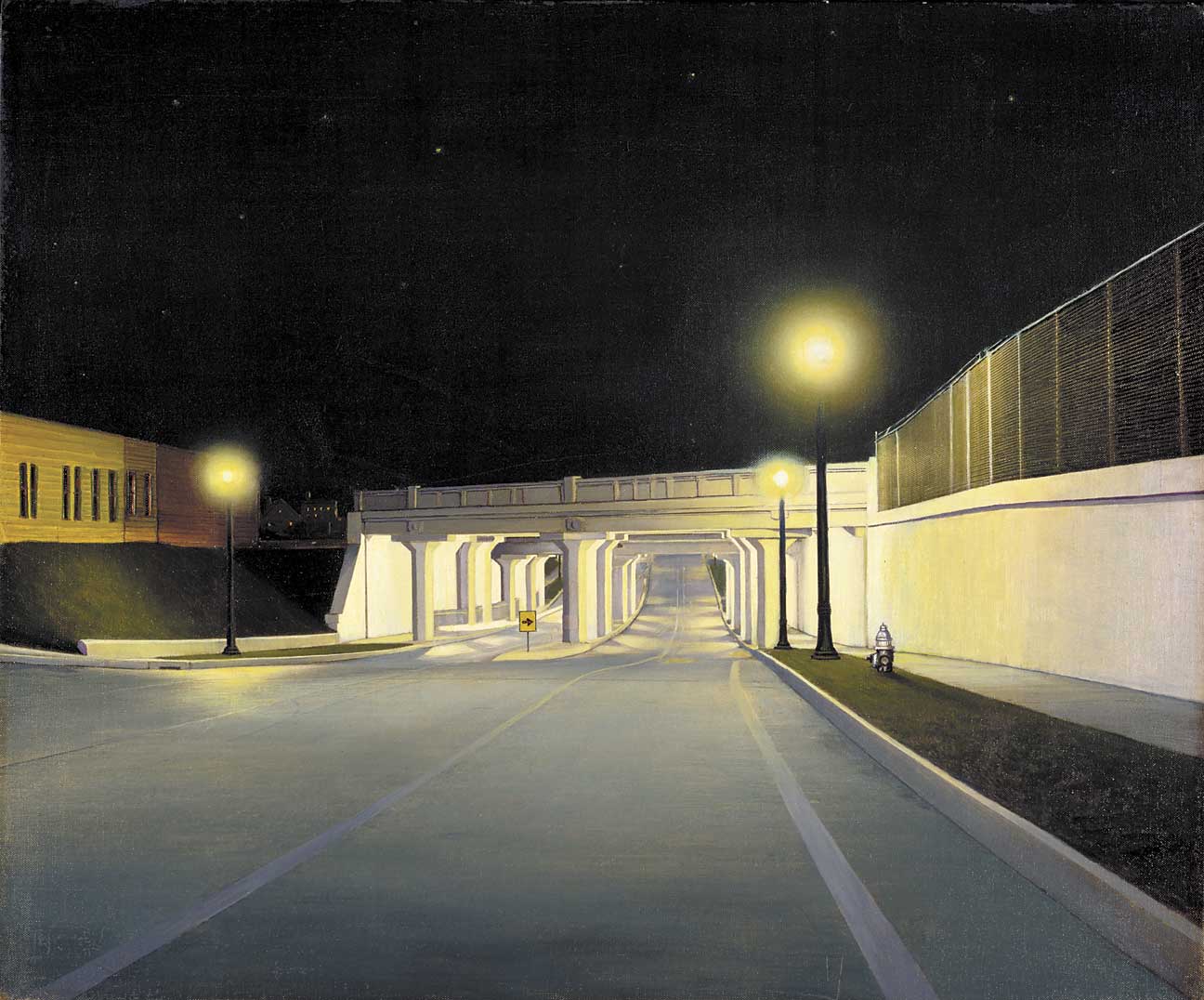

"(Underpass-New York),"

a painting-over-photograph by an unidentified artist that is among the show's most starkly lovely images.

But it's also there in such pieces as

![]()

Paul Kelpe's "Machinery (Abstract #2),"

the show's only nod to abstraction, and a formal study of now-stilled gears. Other street scenes show darkening shadows and emptying sidewalks. Even pictures that are populated, such as

![]()

Saul Berman's "Riverfront,"

depicting New York shipyards, show workers engaged in little besides the busywork of shoveling snow.

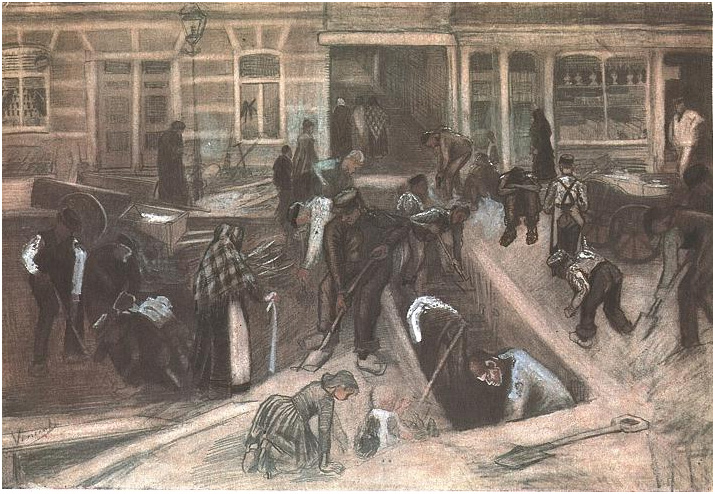

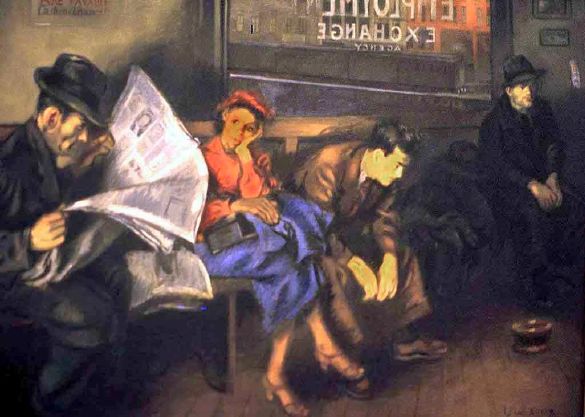

From an excellent article on the show:PWAP artists captured a variety of daily routines characteristic of where they lived. In

![]()

Subway

Lily Furedi (1901–1969) created a sympathetic view of her fellow New Yorkers taking their daily ride below the streets of Manhattan. She focused particularly on a musician who has fallen asleep in his formal working clothes, holding his violin case. The artist would have identified with a musician because her father, Samuel Furedi, was a professional cellist. Such depictions of urban New York abound in PWAP works, since there were far more artists working in the New York region than in any other.

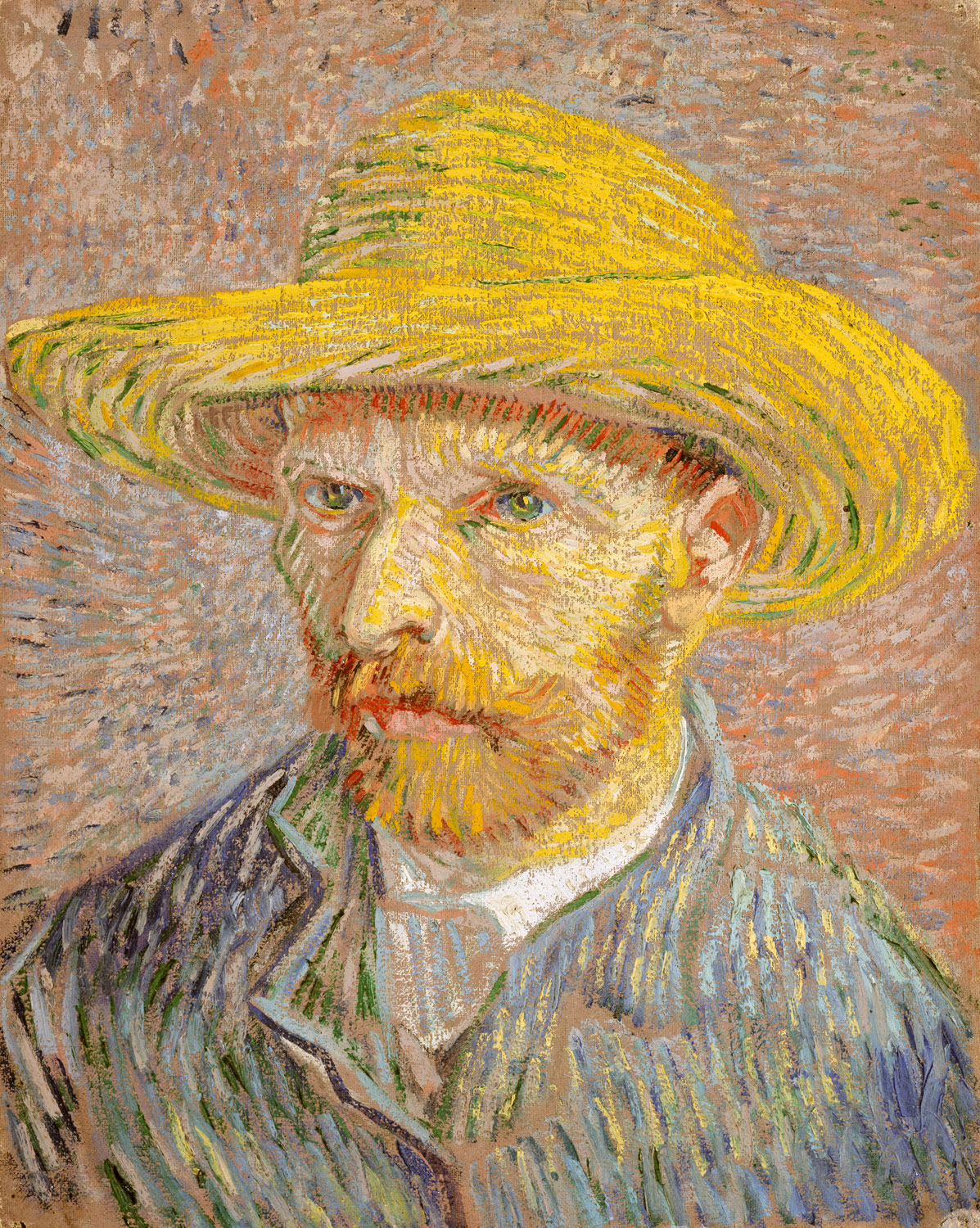

Artist E. Martin Hennings (1886–1956) chose to celebrate the West, painting images of Native American life and the Southwestern landscape. Though much of his early life was spent in Chicago, he moved permanently to New Mexico in 1921 at the age of thirty five, becoming a member of the Taos Society of Artists three years later. Hennings felt a deep love for Taos in particular. In his painting

![]()

Homeward Bound

he painted two Native Americans from Taos Pueblo, the man wrapped in a traditional white blanket while the woman wears a colorful shawl. Hennings linked the two figures to their home landscape by likening them to the tall native sunflowers that stand behind them, silhouetted against the sky with their long stalks gracefully intertwined. This serene painting with its figures in traditional garb calmly going home speaks to Hennings' admiration of the area and its people, and to the endurance of Native American traditions, even in the face of the worst challenges.

From a Smithsonian Magazine article:But the exhibition also underscores a salient fact: when a quarter of the nation is unemployed, three-quarters have a job, and life for many of them went on as it had in the past. They just didn't have as much money. In

![]()

Harry Gottlieb's Filling the Ice House,

painted in upstate New York, men wielding pikes skid blocks of ice along wooden chutes. A town gathers to watch a game in Morris Kantor's Baseball at Night (above). A dance band plays in an East Harlem street while a religious procession marches solemnly past and vendors hawk pizzas in

![]()

Daniel Celentano's Festival.

Drying clothes flap in the breeze and women stand and chat in the Los Angeles slums in

![]()

Tenement Flats by Millard Sheets;

one of the better-known artists in the show, Sheets later created the giant mural of Christ on a Notre Dame library that is visible from the football stadium and nicknamed "Touchdown Jesus."

If there is a political subtext to these paintings, the viewer has to supply it. One can mentally juxtapose

![]()

Jacob Getlar Smith's careworn Snow Shovellers

—unemployed men trudging off to make a few cents clearing park paths—

with the yachtsmen on Long Island Sound in

![]()

Gerald Sargent Foster's Racing,

but it's unlikely that Foster, described as "an avid yachtsman" on the gallery label, intended any kind of ironic commentary with his painting of rich men at play. As always, New Yorkers of every class except the destitute and the very wealthy sat side by side in the subway, the subject of a painting by Lily Furedi; (above) the tuxedoed man dozing in his seat turns out, on closer inspection, to be a musician on his way to or from a job, while a young white woman across the aisle sneaks a glance at the newspaper held by the black man sitting next to her.

Publication ![]() A catalog,

A catalog, fully illustrated in color and co-published by the Smithsonian American Art Museum and D Giles Ltd. in London, features an essay by Roger Kennedy, historian and director emeritus of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History; individual entries for each artwork by Wagner; and an introduction by the museum’s director Broun.

Artworks in the exhibition: Credits and additional images

Section 1: American People![]()

1. Ivan Albright

The Farmer's Kitchen, about 1934

Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 1/8 inches (91.5 x 76.5 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

![]()

2. Robert Brackman

Somewhere in America, 1934

Oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 25 1/8 inches (76.5 x 63.9 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

![]()

3. Kenneth M. Adams

Juan Duran, 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 40 1/8 x 30 1/8 inches (102.0 x 76.5 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

4. J. Theodore Johnson

Chicago Interior, 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 28 x 34 inches (71.2 x 86.4 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

5. E. Martin Hennings

Homeward Bound, 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 30 1/4 x 36 1/4 inches (76.8 x 92.1 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

Section 2: City Life

6. Lily Furedi

Subway, 1934

Oil on canvas, 39 x 48 1/4 inches (99.1 x 122.6 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service

7. Carl Gustaf Nelson

Central Park, about 1934

Oil on canvas, 31 7/8 x 44 inches (81.0 x 111.8 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

8. Millard Sheets

Tenement Flats, 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 40 1/4 x 50 1/4 inches (102.1 x 127.6 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service

9. Daniel Celentano

Festival, about 1933-1934

Oil on canvas mounted on fiberboard, 48 1/8 x 60 1/8 inches (122.3 x 152.8 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

![]()

10. Ilya Bolotowsky

In the Barber Shop, 1934

Oil on canvas, 23 7/8 x 30 1/8 inches (60.6 x 76.5 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

Section 2: Leisure11. Gerald Sargent Foster

Racing, 1934

Oil on canvas, 22 1/8 x 34 1/8 inches (56.2 x 86.6 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service

12. Agnes Tait

Skating in Central Park, 1934

Oil on canvas

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

13. Julia Eckel

Radio Broadcast, 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 40 1/8 x 55 5/8 inches (102.0 x 141.2 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

14. Morris Kantor

Baseball at Night, 1934

Oil on linen, 37 x 47 1/4 inches (94.0 x 120.0 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Mrs. Morris Kantor

15. Attributed to Martha Levy

Winter Scene, 1934

Oil on fiberboard, 21 1/2 x 27 3/8 inches (54.6 x 69.5 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

Section 3: Labor

16. Earle Richardson

Employment of Negroes in Agriculture, 1934

Oil on canvas, 48 x 32 1/8 inches (121.8 x 81.6 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

17. Jacob Getlar Smith

Snow Shovellers, 1934

Oil on canvas, 29 7/8 x 40 1/8 inches (76.0 x 101.9 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

18. Harry Gottlieb

Filling the Ice House, 1934

Oil on canvas

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

![]()

19. Douglass Crockwell

Paper Workers, 1934

Oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 48 1/4 inches (91.7 x 122.4 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

![]()

20. Pino Janni

Waterfront Scene, 1934

Oil on canvas, 40 1/8 x 53 3/4 inches (101.8 x 136.6 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

21. Tyrone Comfort

Gold Is Where You Find It, 1934

Oil on canvas, 40 1/8 x 50 1/8 inches (101.9 x 127.3 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service

![]()

22. Harry W. Scheuch

Workers on the Cathedral of Learning, 1934

Oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 26 1/8 inches (76.5 x 66.5 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

23. Harry W. Scheuch

Finishing the Cathedral of Learning, 1934

Oil on canvas, 40 1/4 x 30 1/4 inches (102.3 x 76.9 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

Section 4: Industry

24. Arnold Ness Klagstad

Archer Daniels Midland Elevator, 1933-1943

Oil on canvas, 22 1/4 x 28 1/8 inches (56.6 x 71.4 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

25. Raymond White Skolfield

Natural Power, 1934

Oil on canvas, 34 1/8 x 36 1/8 inches (86.8 x 91.8 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

26. Ray Strong

Golden Gate Bridge, 1934

Oil on canvas, 44 1/8 x 71 3/4 inches (112.0 x 182.3 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service

27. E. Dewey Albinson

Northern Minnesota Mine, 1934

Oil on canvas, 40 x 50 1/8 inches (101.6 x 127.2 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

28. Austin Mecklem

Engine House and Bunkers, 1934

Oil on canvas, 38 x 50 1/4 inches (96.5 x 127.6 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

29. Max Arthur Cohn

Coal Tower, 1934

Oil on canvas, 22 1/8 x 28 inches (56.2 x 71.2 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

30. Carl Redin

At Madrid Coal Mine, New Mexico, 1934

Oil on canvas, 30 x 38 inches (76.2 x 96.5 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

31. William Arthur Cooper

Lumber Industry, 1934

Oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 29 7/8 inches (61.3 x 75.9 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

32. Karl Fortess

Island Dock Yard, about 1934

Oil on canvas, 32 1/4 x 48 1/8 inches (81.8 x 122.2 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

33. Paul Kelpe

Machinery (Abstract #2), 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 38 1/4 x 26 3/8 inches (97.0 x 67.0 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

34. Joe Jones

Street Scene, 1933

Oil on canvas, 25 1/8 x 35 7/8 inches (63.7 x 91.1 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

Section 5: The City

![]()

35. Thomas James Delbridge

Lower Manhattan, about 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 26 1/8 x 30 1/4 inches (66.3 x 76.9 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

36. Unidentified

(Underpass--New York), 1933-1934

Oil on photograph on canvas mounted on paperboard,

19 7/8 x 23 7/8 inches (50.6 x 60.8 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the

Internal Revenue Service through the General Services Administration

![]()

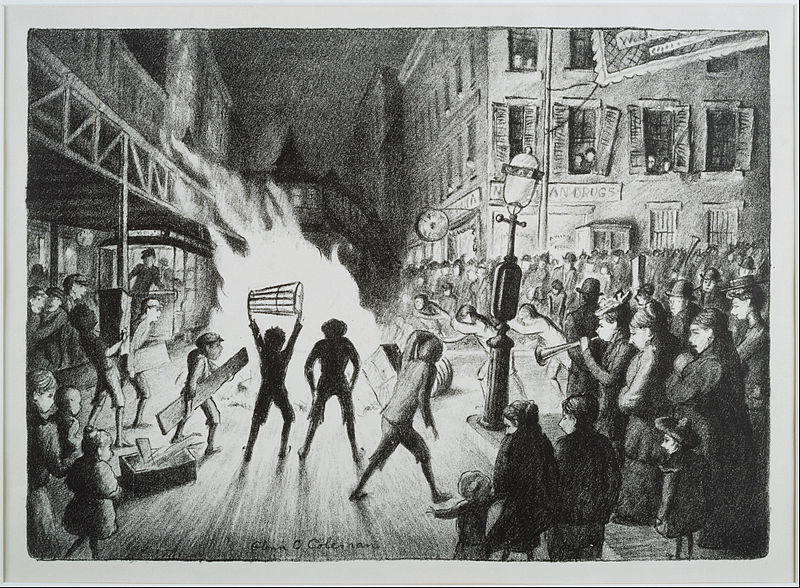

37. Charles L. Goeller

Third Avenue, about 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 1/8 inches (91.4 x 76.4 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

![]()

38. Beulah R. Bettersworth

Christopher Street, Greenwich Village, 1934

Oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 24 1/4 inches (76.5 x 61.5 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service

39. Herman Maril

Sketch of Old Baltimore Waterfront, 1934

Oil on fiberboard, 18 1/8 x 14 1/8 inches (46.0 x 36.0 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

40. John Cunning

Manhattan Skyline, about 1934

Oil on canvas, 32 1/8 x 48 1/8 inches (81.5 x 122.2 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

41. Saul Berman

River Front, 1934

Oil on canvas, 16 x 24 inches (40.7 x 61.1 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

42. Robert A. Darrah Miller

Farm, about 1934

Oil on canvas, 22 x 28 1/8 inches (55.9 x 71.5 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

43. Paul Benjamin

Cross Road--Still Life, about 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 28 1/4 x 26 1/4 inches (71.6 x 66.6 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service

44. Arthur E. Cederquist

Old Pennsylvania Farm in Winter, 1934

Oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 40 1/8 inches (76.5 x 102.0 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

45. O. Louis Guglielmi

Martyr Hill, about 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 22 x 32 inches (55.9 x 81.4 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

46. Erle Loran

Minnesota Highway, 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 36 inches (76.5 x 91.5 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

Section 6: The Country

47. Kenjiro Nomura

The Farm, 1934

Oil on canvas, 38 1/4 x 46 1/8 inches (97.2 x 117.1 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

![]()

48. Gale Stockwell

Parkville, Main Street, 1933

Oil on canvas, 28 1/4 x 35 3/8 inches (71.8 x 90.0 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

Section 7: Nature

49. Paul Kirtland Mays

Jungle, 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 42 1/4 x 75 1/2 inches (107.3 x 191.7cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service

50. Alice Dinneen

Black Panther, 1934

Oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 24 1/8 inches (76.5 x 61.4 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

51. Ila McAfee Turner

Mountain Lions, 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 42 inches (91.9 x 106.8 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

52. Winthrop Duthie Turney

Selection from Birds and Animals of the United States, about 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 32 x 36 1/8 inches (81.3 x 91.6 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the General Services Administration

53. Leo Breslau

Plowing, 1934

Oil on wood: plywood, 29 7/8 x 35 7/8 inches (75.8 x 91.2 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

54. Paul Kauvar Smith

The Sky Pond, 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 42 x 50 1/8 inches (106.8 x 127.4 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

![]()

55. Charles Reiffel

Road in the Cuyamacas, about 1933-1934

Oil on canvas, 40 1/8 x 50 3/8 inches (101.9 x 128.0 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

56. Ross Dickinson

Valley Farms, 1934

Oil on canvas, 39 7/8 x 50 1/8 inches (101.4 x 127.3 cm.)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor

.jpg/752px-RAFAEL_-_Sue%C3%B1o_del_Caballero_(National_Gallery_de_Londres,_1504._%C3%93leo_sobre_tabla,_17_x_17_cm).jpg)

_Frederic_Edwin_Church.jpg/800px-Sunrise_(1847)_Frederic_Edwin_Church.jpg)