ARTISTS

Beckmann, Max

Dix, Otto

Feininger, Lyonel

Gerstl, Richard

Grosz, George

Heckel, Erich

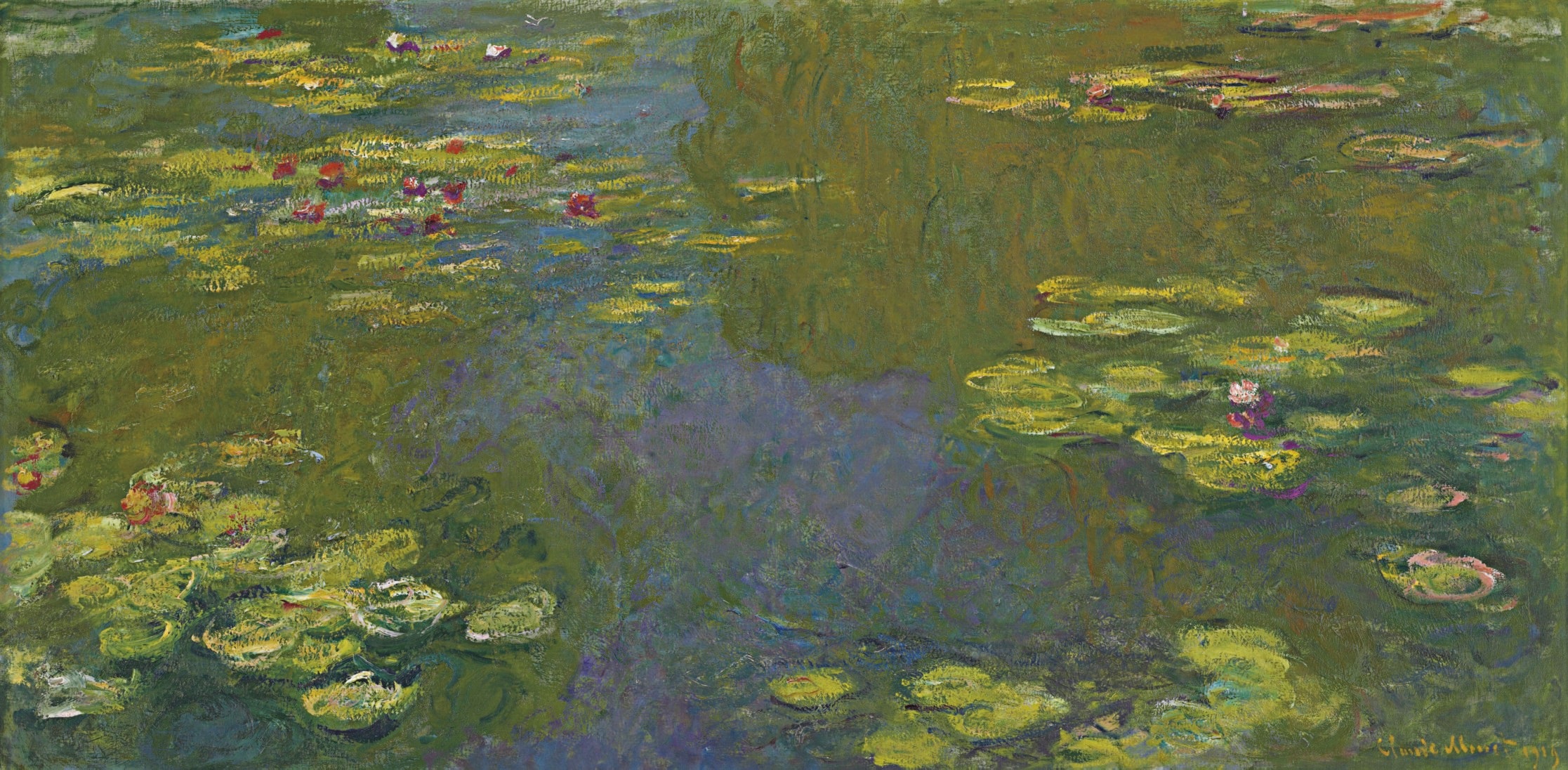

Kandinsky, Wassily

Kirchner, Ernst Ludwig

Klee, Paul

Kokoschka, Oskar

Kubin, Alfred

Macke, August

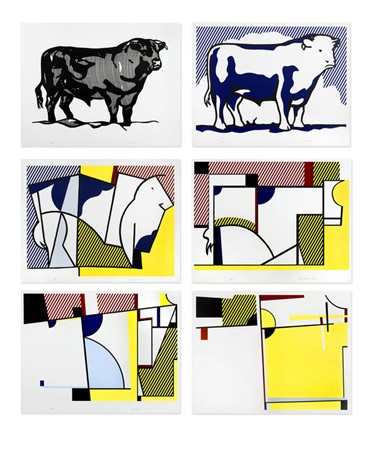

Marc, Franz

Mueller, Otto

Nolde, Emil

Pechstein, Hermann Max

Schiele, Egon

Schmidt-Rottluff, KarlRealism and abstraction are frequently cast as opposing forces in modernism’s developmental narrative. For reasons that had to do less with art-historical inevitably than with geopolitics, abstraction was declared victorious in the United States after World War II. Reflecting wartime alliances, American abstraction traced its lineage to France, while the Germanic tradition of figural Expressionism was largely sidelined. To the extent that Germany’s contributions to modernism were acknowledged, Munich’s

Blaue Reiter group, which experimented most overtly with abstraction, received greater attention than the comparatively representational work of artists based elsewhere in German-speaking Europe. Wassily Kandinsky’s esoteric theories, endorsed by Galka Scheyer on the West Coast and Hilla Rebay at the fledgling Guggenheim Museum (originally the Museum of Non-Objective Painting) in New York, seemed to affirm the formalist dogma that dominated the American art world in the third quarter of the twentieth century.

However, neither Kandinsky nor his Expressionist colleagues in Germany and Austria believed that art should be free of all extrinsic content, or as the critic Clement Greenberg put it, that an artist should be concerned solely with the “arrangement of spaces, surfaces, shapes, colors, etc., to the exclusion of whatever is not necessarily implicated in these factors.” In the

Blaue Reiter Almanac, Kandinsky described two fundamental formal approaches, “the great realism” and “the great abstraction,” both of which, he said, ultimately serve the same end: to express “the inner resonance of the thing.” The German critic Paul Fechter, who authored the first book on the subject in 1914, similarly identified two strands of Expressionism: the “extensive,” which retains ties to recognizable subject matter, and the “intensive,” which entirely renounces such imagery. Whether realist or abstract in their orientation, Expressionists were driven by a need to re-envision the world.

Germany and Austria industrialized relatively late and, unlike England and France, had failed to establish effective democratic institutions to channel the concomitant social upheaval. Artists coming of age in German-speaking Europe at the dawn of the twentieth century objected equally to the rigidity of the old aristocratic order and to the materialism associated with bourgeois capitalism.

Inspired by the Nietzschean ideal of human perfectibility, the North-German

Brücke group hoped to build a “bridge” to a better future by uniting “the entire younger generation” in opposition to “entrenched and established tendencies.” For the most part, first-generation Expressionists eschewed political solutions, instead focusing on spiritual self-improvement. “When religion, science and morals…are in danger of failing,” Kandinsky observed, “man turns his eyes away from the exterior world, onto himself.” At the same time, many Expressionists sought a connection to universal forces beyond the self, situated in nature, the infinite or the occult.

Although Germany’s component principalities made remarkable contributions to the fields of music, literature and philosophy prior to national unification in 1871, the territory as a whole had historically ceded artistic leadership to France. The chain of “isms” emanating from the French capital—Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, Symbolism, Fauvism, Cubism, “Primitivism”—continued to inform Germanic modernism, but the German responses were nonetheless distinct. Whereas French artists tended to deconstruct their subjects aesthetically, the Expressionists attacked them metaphysically.

The French (with the notable exception of Paul Gauguin) responded to “Primitivism” in largely formal terms, while German artists sought an Edenic ideal in cultures untouched by the forces of modern civilization. Symbolism—a multinational movement that attempted to find objective visual correlatives for subjective states—had a far more profound impact in German-speaking Europe than in France.

Germans and Austrians proved especially receptive to fin-de-siècle ideas that revealed, or purported to reveal, the truth behind surface appearances. Kandinsky equated the discovery of subatomic particles with the literal dissolution of matter. X-rays, which make it possible to see through solid objects, came to be associated with clairvoyance. The physicist Ernst Mach contended that there is no real difference “between bodies and sensations . . . between what is without and what is within, between the material world and the spiritual world.”

Enormously popular in German-speaking Europe, Theosophy posited that the “astral plane” could be accessed through a “subtle invisible essence or fluid” that radiates from all living beings. Artists were encouraged, by such contemporary thinkers as Joséphin Péladan, Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach and Stanislaw Przbyszewski, to consider themselves “seers,” possessed of a vision that was spiritual as well as artistic.

Accordingly, the Expressionists transformed color, line and composition into vehicles for exploring the mystical, emotional or psychological underpinnings of their subjects.

Urfarben (the “source colors” of the rainbow), which had been used by the Neo-Impressionists to replicate optical effects, lost their connection to observable reality. Not only are these colors purer and brighter than intermediate mixed hues, but they carry greater emotional weight, especially when clashing complementaries are juxtaposed.

“Color,” wrote Kandinsky, “is a means to exercise a direct influence on the soul.” In his 1810 book,

Zur Farbenlehre (On the Lessons of Color), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had proposed a vocabulary of symbolic color equivalencies: red was associated with beauty, orange with nobility, yellow with goodness, green with utility, blue with mediocrity and so on. The Theosophists also believed in mystical color associations, though theirs were somewhat different. (Blue, for example, connoted purity of thought.) Clairvoyants could ostensibly see these colors emanating from human bodies as “auras” and “thought forms”—phenomena painted variously by Kandinsky, Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele.

Like color, Expressionist line did not adhere to the strict requirements of realistic verisimilitude. Japanese woodblock prints and

Jugendstil graphic design, both of which jettisoned three-dimensional interior modeling in favor of evocative contours, were decisive influences. The woodcuts of Gauguin and Edvard Munch, caricatures from the satirical magazine

Simplicissimus, Medieval religious imagery and tribal carvings added an element of exaggeration to the mix. German and Austrian artists saw line as an expressive tool in its own right. Many of them employed jagged, angular or broken lines and bizarre striations for emotional effect. Some aimed for concision and economy of means, while others retraced outlines repeatedly to arrive at a quintessential form.

Drawing the moving figure was a practice common among the

Brücke artists in Dresden, as well as Schiele and Kokoschka in Vienna. These men all sought to capture spontaneous visual responses, what Ernst Ludwig Kirchner called “the ecstasy of first sight.” Kandinsky, on the other hand, developed a more cerebral language of symbolic lines.

Whether approached in aesthetic or metaphysical terms, line constituted a crucial boundary between figure and ground, subject and surrounding cosmos. From Gothic woodcuts to

Jugendstil design, many of the sources that influenced the Expressionists treated positive and negative space equally. The resultant two-dimensional flattening of the picture plane was especially well suited to landscapes, whose components (buildings, sky, trees, mountains, etc.) can readily be reduced to abstract shapes.

By visually uniting these elements, artists conveyed a sense of mystical harmony with and within the natural or human-built environment. Lyonel Feininger and Schiele each interpreted (or misinterpreted) Cubism in this vein. Kandinsky, who between 1910 and 1913 gradually relinquished representational subject matter altogether, equated the picture plane with infinity or utopia. Fragmentation of form could be used by artists with a more figural bent to suggest the immateriality of the soul and the fusion of the body with the spirit realm.

But there is a limit to how much the human figure can be abstracted and still remain, well, human. The contrast between artistic representations of “real” people and the two-dimensional surfaces upon which they “lived” was more likely to evoke alienation than harmony. For some Expressionists, the line dividing figure from ground, physical from spiritual, was an impermeable barrier that only served to highlight the fragility of the self in the face of a surrounding existential void.

Despite certain broad affinities among its artists, Expressionism was not a coherent style in the manner of Impressionism or Cubism. German-speaking Europe had multiple cultural centers, essentially revolving around its different art academies. In the final decade of the nineteenth century, a number of Secession initiatives arose to counter the dominance of those academies. The Secessions did not espouse specific stylistic programs, but rather sought to provide exhibition outlets for the rising avant-garde and to foster international cultural exchange. Collectively, their aim might be summed up by the motto of the Vienna Secession: “To the age its art; to art its freedom.”

As a younger generation came to the fore in the twentieth century, the Secessions foundered. Nevertheless, they bequeathed to their Expressionist successors a mandate to pursue the

Kunstwollen—artistic aims—of the time on their own individual terms. Artists, dispersed among the preexisting academic centers in such cities as Dresden, Berlin, Munich and Vienna, took up the challenge in disparate ways.

Die Brücke, established in Dresden in 1905, was the first and, initially, the most cohesive Expressionist group. Its founding members, Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Fritz Bleyl, were former architecture students at the Dresden Technical Institute, and though the curriculum there covered drawing, only Kirchner, who spent one semester at a progressive studio school in Munich, had any dedicated fine arts training. Kirchner brought back from Bavaria an appreciation for

Jugendstil graphics and Gothic woodcuts, as well as an interest in primeval cultures, which was soon affirmed by the Oceanic and African art in the Dresden ethnographic museum. This yearning for the “primitive” would take Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein (both of whom joined

Die Brücke in 1906) to the South Seas in 1913-14, and Otto Mueller (a member from 1910-13) to the Balkans in the 1920s.

At first the

Brücke artists attempted to create a refuge from modern civilization in their own backyard. Working communally in a storefront studio, they endeavored (in Kirchner’s words) “to bring art and life into harmony with one another.” During the warmer months, they decamped to the countryside, where they pursued a shared resolve to “study the nude in free naturalness.”

Printmaking was central to the

Brücke initiative, both in forging a collective identity and in soliciting financial support from “passive members,” who were rewarded with an annual print portfolio. Woodcut, with its melding of Medieval and contemporary influences, its stark contrasts and exaggerated forms, is the graphic technique most often associated with

Die Brücke. But the artists were equally innovative in their etchings and lithographs, transforming what had been essentially reproductive techniques into original expressive vehicles.

The group ethos disintegrated after 1911, when Heckel, Kirchner and Schmidt-Rottluff decided to join Mueller and Pechstein in Berlin. Leadership conflicts caused

Die Brücke formally to disband in 1913.

While Germans at the turn of the twentieth century were struggling to cement a national identity, Austria-Hungary was being torn apart by ethnic, economic and political tensions across its far-flung empire. There was little unity among the Austrian Expressionists, little of the utopianism that marked the Germans’ quest for radical transformation.

Brücke artists tried to subordinate themselves to a communal ideal; Austrians were more concerned with redefining the self in the face of intellectual challenges by such contemporaries as Mach and Sigmund Freud. Kokoschka, who claimed to have “x-ray vision,” aspired to extract the souls of his subjects from their external physical shells. Schiele probed his own persona incessantly, testing the boundary between pretense and essence. In his oils, Schiele continued a tradition of Symbolist allegory that owed much to the example of Gustav Klimt. Mortality and human frailty were recurring themes for both artists.

The

Jugendstil-inflected work of Klimt and the Wiener Werkstätte strongly influenced Kokoschka and Schiele during their student years, but by 1910 each had emerged with a distinctive Expressionistic idiom. Kokoschka’s raw, painterly style derived from artifacts he had seen in Vienna’s ethnographic museum. Schiele, on the other hand, retained a propensity for elegant lines and structured compositions that can be attributed to his more conventional academic training and to Klimt’s lingering impact. From 1910 on, Kokoschka spent considerable stretches of time in Germany, where he made contact with members of

Die Brücke and

Der Blaue Reiter. Appropriating the heavier impastos and bolder colors of those colleagues, he hereafter was frequently classified as a “German” Expressionist. Although Schiele also exhibited in Germany, he had little success there. Both geographically and artistically, he remained isolated in the Austrian environment. Austria’s third great Expressionist, Richard Gerstl, who committed suicide in 1908, was totally unknown until his rediscovery in 1931. Independently working his way through the formal and tonal lessons of Neo-Impressionism, Gerstl arrived at the first iteration of what was later called “Abstract Expressionism.”

Less disjointed than the Austrian Expressionists, but more informal that the

Brücke group,

Der Blaue Reiter was an alliance of international artists who exhibited together in Germany between 1911 and 1913. Because this period coincided with the publication of Kandinsky’s most famous theoretical writings, in the

Blaue Reiter Almanac and

On the Spiritual in Art, his ideas came to be associated with artists whose styles were actually quite diverse. Kandinsky had moved to Munich in 1896, along with two other Russian artists, Alexei Jawlensky and Marianne Werefkin. Soon Kandinsky assumed a leadership position, founding the Phalanx group and school in 1901, and in 1909, the

Neue Künstlervereinigung (New Artists’ Association), an alternative to the increasingly conservative Munich Secession. In addition to the three Russians and Gabriele Münter (a former Phalanx student), the

NKV pulled into its orbit Feininger, Alfred Kubin, Paul Klee, August Macke and Franz Marc—all of whom later showed with

Der Blaue Reiter.

During the years of their association, the

Blaue Reiter artists, each in his or her own way, explored the distinction between what Kandinsky called the “great realism” and the “great abstraction.” “Primitivism” (here incorporating not just tribal art, but domestic folk art, the work of self-taught painters like Henri Rousseau, children’s art and, for Klee and Kubin, the art of the mentally ill) represented the “great realism”: art without artifice. By emulating untrained creators,

Blaue Reiter artists hoped to recapture a primordial innocence that would enable them to reveal their subjects’ “inner truths.” Marc’s search for an unspoiled, “natural” state of consciousness prompted him to identify with nonhuman animals and to try to depict the world through their eyes.

The path to the “great abstraction” lay beyond nature, in the realm of pure imagination. Kandinsky was looking for a visual equivalent to music; an art that would be free of any representational associations. “In color,” Macke declared, “there is counterpoint, violin, ground bass, minor, major, as in music.” Klee and Feininger, both trained as violinists, tried to imbue their art with the emotional immediacy of music. Nonetheless, neither they nor Kubin, Münter, Jawlensky or Werefkin ever entirely gave up recognizable imagery. Even Kandinsky, slow to digest his own philosophical pronouncements, was still painting landscape forms as late as 1913. He worried that a completely abstract artwork might too easily be confused with a “necktie or a carpet” pattern—confounding the essential link to the spiritual. Macke and Marc were the only other

Blaue Reiter artists to break through, albeit tentatively, to abstraction. When they perished in World War I, Kandinsky became the sole surviving non-objective painter among the first-generation Expressionists.

The Expressionists’ search for spiritual authenticity was an implicit protest against capitalistic materialism. Nevertheless, after the carnage of World War I and the political turmoil that followed, their approach appeared hopelessly bourgeois. Prewar utopianism was superseded by the practical necessity of dealing with the socioeconomic problems of the Weimar era. Denounced as self-indulgent and incomprehensible, abstraction was deemed incapable of addressing these new realities. The artists who came of age in Germany after 1918, however, readily adopted the more realistic innovations of their prewar predecessors.

There was, in fact, considerable stylistic continuity between the first- and second-generation Expressionists. Fragmented images, erratic lines and crazed croppings were ideally suited to Otto Dix’s on-the-spot renderings of trench warfare. These same tropes were subsequently used by Max Beckmann to convey the sense of dislocation and unease endemic to Weimar society. Expressive exaggeration, verging on caricature in the case of Dix and George Grosz, was a perfect way to critique contemporary decadence. Often the compositions of all three artists are packed with detail, compressed into a claustrophobic, flattened space. At other times, isolated figures are presented as icons of alienation. By means of these formal devices, each artist was able to transform his subjective experiences into an emotionally compelling commentary on the human condition. Expressionism’s most significant legacy lies in the creation of a pictorial language that amalgamates abstract elements with references to the visible world.

All Photos courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York:

MAX BECKMANN (German, 1884-1950)

![]()

1. Dinner Party

Circa 1919. Woodcut on thin cream laid Japan paper. Signed, lower right, and inscribed "Probedruck" (trial proof), lower left. 12" x 4" (30.2 x 10 cm). One of six documented trial proofs; probably hand-printed by the artist. Hofmaier 158/A.

![]()

2. The Tall Man

1921. Etching on cream wove paper, worked over in ink. Signed and dated, lower right, and inscribed "Luftschaukel (Handprobedruck)" (Air-Swing [hand-pulled proof]), lower left. 12" x 8 1/8" (30.5 x 20.6 cm). Plate 5 from the cycle

The Annual Fair. Unique proof of the first state, hand-printed and extensively worked over by the artist in anticipation of additions and alterations to the plate in the second state. Hofmaier 195/I.

![]()

3. Merry-Go-Round

1921. Drypoing on laid Japan paper. Signed and with Marées Gesellschaft chop, lower right. 20 7/8" x 15" (53 x 38.1 cm). Plate 7 from the cycle

The Annual Fair. From the edition of 75 impressions on this paper. Hofmaier 197/IIBa.

4. Portrait of Irma Simon

1924. Oil on canvas. Signed and dated, upper right. 48" x 23 5/8" (122 x 60 cm). Göpel 235.

![]()

5. Reclining Woman

1945. Pen, ink and pencil on watermarked laid paper. Signed, dated and inscribed "A," lower right. 13" x 14 1/8" (33 x 35.9 cm). Study for

Afternoon (Göpel 724).

OTTO DIX (German, 1891-1969)

6. Madonna

1914. Watercolor, gouahce, ink and pencil on thin off-white wove paper. Signed and dated, lower right; titled and inscribed "Z. 3081," lower center. 19 5/8" x 16 7/8" (49.8 x 42.9 cm). Pfäffle A/G 1914/2.

![]()

7. Trench with House

1915. Pencil on off-white watermarked laid paper. Signed, lower right. 11 3/8" x 8 1/4" (28.9 x 21 cm). Lorenz WK 5.3.19.

![]()

8. Grenade Crater in a House

1916. Pencil on heavy tan wove paper. Signed, lower right. 11 1/4" x 11 1/4" (28.6 x 28.6 cm). Lorenz WK 5.3.24.

![]()

9. Soldier

Circa 1917. Black chalk on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, upper right. 16" x 5 1/2" (40.6 x 39.4 cm). Lorenz WK 6.4.27.

![]()

10. Apotheosis

1919. Woodcut on off-white wove paper. Signed and titled, lower right; inscribed "Handdruck" (hand-pulled print), lower left. 11 1/8" x 7 7/8" (28.3 x 20 cm). One of a few hand-pulled proofs before the edition of 30 impressions published in 1922. Karsch 30/a.

![]()

11. Street Noise

1920. Woodcut on white wove paper. Signed and dated, lower right, and titled, lower center; numbered 25/30, lower left. 19 7/8" x 9 1/4" (50.5 x 23.5 cm). Plate 4 from the portfolio

Woodcuts II: 9 Woodcuts. From the edition of 30 impressions. Karsch 26/Bb.

![]()

12. Reclining Female Semi-Nude

1929. Red crayon on thin cream wove paper. Signed, upper right. 12 1/4" x 17 5/8" (31.1 x 44.8 cm). Lorenz NSk 12.3.3.

![]()

13. The Madam

1923. Color lithograph on beige laid paper. Signed, lower right, and numbered 64/65, lower left. 19" x 14 1/2" (48.3 x 36.8 cm). From the edition of 65 impressions. Karsch 69/II.

![]()

14. Mediterranean Sailor

1923. Lithograph on heavy smooth off-white wove paper. Signed, lower right, and numbered 4/55, lower left. 18 1/2" x 12 1/2" (47 x 31.8 cm). From a total edition of 55 impressions. Karsch 59/b.

RICHARD GERSTL (Austrian, 1883-1908)

![]()

17. Nude in Garden

1908. Oil on canvas. Estate stamp, verso. 47 5/8" x 39" (121.1 x 99.1 cm). Kallir 48. Private collection.

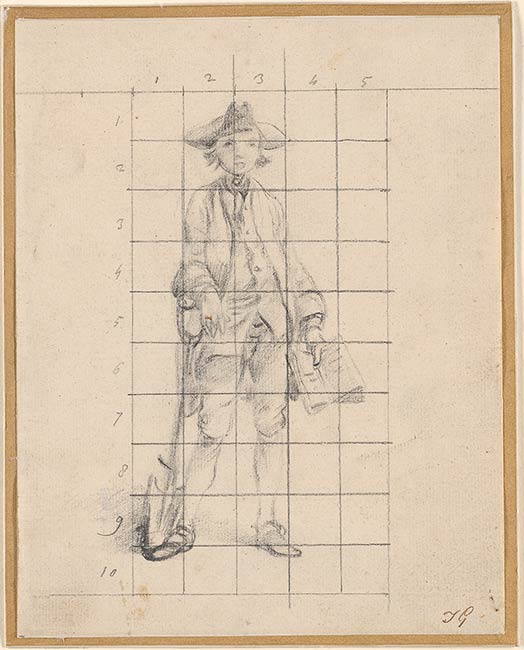

GEORGE GROSZ (German 1893-1959)

18. Eccentric Dance

1914. Pencil on thin cream laid Velin paper. Titled, lower center. Estate stamp, no. 5-183-6, verso. 11 3/8" x 8 7/8" (29 x 22.5 cm).

![]()

19. Reclining Female Nude with Upraised Head

1927. Pencil on heavy tan wove paper. Signed, lower right, and inscribed "III/27," upper right corner. 12 3/8" x 17 3/8" (31.4 x 44.1 cm).

WASSILY KANDINSKY (French (Born Russian), 1866-1944)

![]()

29. Archer

1908-09. Colored woodcut on cream watermarked laid paper. Signed, lower rgiht. 6 1/2" x 6" (16.5 x 15.2 cm). Roethel 79. Private collection.

![]()

30. Small Worlds

1922. Portfolio of twelve prints (six lithographs, four drypoints, and two woodcuts). Title page dedicated to Ilse and Walter Gropius, lower left. Individual prints signed, lower right. 10 1/2" x 11 7/8" (26.7 x 30 cm). From the edition of 230 portfolios published by Propyläen-Verlag, Berlin, 1922, and printed by the Staatliches Bauhaus, Weimar. Private collection.

ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER (German, 1880-1938)

![]()

32. Archer in Moritzburg (Erich Heckel)

1909. Pen and ink on brownish paper. Estate stamp and registration numbers, "F Dre/Bf 6,""C 2110" and "K 4901," verso. 17 1/4" x 13" (43.8 x 33 cm). Registered with the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern, Switzerland.

![]()

33. Dance Group (Three Dancers)

Circa 1910. Pencil on cream wove paper. Numbered 15, verso. 8 1/4" x 6 1/4" (21 x 15.9 cm). Registered with the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern, Switzerland.

![]()

34. Man and Woman Dancing

Circa 1916. Graphite on thin off-white wove paper. 6 3/8" x 7 7/8" (16.2 x 20 cm). Registered with the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern, Switzerland. Formerly collection Robert Lehman.

![]()

35. Fanny in Armchair (Fanny Wocke)

1916. Lithograph on thin yellow wove paper. Signed, lower right, and inscribed "Handdruck" (hand-print), lower left. Titled "Fanny" and with estate stamp and registration number, L450, verso. 23 1/4" x 19 3/4" (59 x 50 cm). One of seven known impressions; hand-printed by the artist. Gercken 813.

![]()

36. Making Hay

1924. Drypoint in brown on heavt white wove paper. Signed and numbered "111," lower right; titled and dated, lower center. Estate stamp and registration number, R 489 II, verso. 11 3/4" x 9 7/8" (29.8 x 25.1 cm). One of six known impressions. To be included in Volume VI of Günther Gercken's catalogue raisonné; 1466/II. Dube R. 510.

OSKAR KOKOSCHKA (Austrian, 1886-1980)

38. Wiener Werkstätte Postcards

1906-08. Five color lithographs on heavy card stock. Each 4 7/8" x 3 1/8" (12.1 x 7.9 cm). Published by the Wiener Werkstätte. Wingler/Welz, 3, 4, 14, 15 and 17.

39. The Dreaming Youths

1908. Illustrated book with eight color lithographs and three line engravings. Numbered XII inside back cover. 9 5/8" x 11 3/4" x 3/8" (24.4 x 29.8 x 0.9 cm). One of 275 copies (from a total of 500 printed by the Wiener Werkstäyye in 1908) published in 1917 by Kurt Wolff. Wingler/Welz 22-29.

![]()

40. Sleeping Woman in a Deck Shair (Alma Mahler)

1913. Red crayon on thin tan wove paper. Initialed, lower left. 13 5/8" x 8 7/8" (34.6 x 22.5 cm). From a series of drawings of Alma Mahler on a balcony in Naples. Weidinger/Strobl 521.

![]()

41. The Last Judgement

1913. Chalk, pen and ink on thin cream tracing paper. Initialed, lower right. 14 3/4" x 11 5/8" (37.5 x 29.5 cm). Study for the lithograph

Columbus in Chains (Wingler/Welz 45). Weidinger/Strobl 531.

ALFRED KUBIN (Austrian, 1877-1959)

![]()

42. Saint Christopher

Circa 1912-15. Pen and ink on buff laid paper. Signed, lower right, and titled, lower left. 14 1/8" x 10 3/8" (35.9 x 26.3 cm).

![]()

43. Witches' Sabbath

1918. Pen and ink on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, lower rgiht, and titled "Walpurgisnacht," lower left. 10 1/4" x 14 1/8" (26 x 35.9 cm).

AUGUST MACKE (German,1887-1914)

![]()

44. Greeting

1922. Linocut on heavy beige wove paper. Bauhaus blindstamp, lower left edge. Inscribed "August Macke: Begrußung" by Elisabeth Macke, verso. 9 5/8" x 8 7/8" (24.4 x 22.5 cm). Plate 8 from the portfolio

Bauhaus Prints: New European Graphics, publihed by Staatliches Bauhaus, Weimar, 1921.

FRANZ MARC (German, 1880-1916)

![]()

45. Fantastic Creature

1912. Color woodcut on white laid tissue paper. Signed, lower left. 5 3/4" x 8 5/8" (14.6 x 21.9 cm). One of 60 impressions included in the deluxe edition of

The Blaue Reiter Almanac, published by Reinhard Piper & Co., Munich, 1912. Hoberg/Jansen 24/3. Private collection.

![]()

46. The Shepherdess

1912. Woodcut on cream Japan paper. Stamped "Handdruck vom Originalholzstock bestätigt" (authorized hand-print from the original wood block) and signed by Maria Marc, verso. 8 3/4" x 3" (22.2 x 7.6 cm). From the first edition of 21 known prints. Hoberg/Jansen 29/1.

![]()

47. Genesis II

1914. Woodcut in black, yellow and green on thin off-white laid paper. 9 1/2" x 7 7/8" (24.1 x 20 cm). Three color print printed from three blocks. Hoberg/Jansen 42/2.

EMIL NOLDE (German, 1867-1956)

![]()

50. Head of an Apostle

1909. Watercolor and pen and ink on thin watermarked cream wove paper. Signed, lower right. 10 1/2" x 8 1/4" (26.7 x 21 cm). Authenticated by Prof. Dr. Manfred Reuther, May 7, 2017.

![]()

52. Christ and the Sinner

1911. Etching on heavy off-white wove paper. Signed, lower right. 11 7/8" x 9 3/4" (30.2 x 24.8 cm). One of 6 impressions in this state. Schiefler/Mosel R 155/V.

![]()

53. Prophet

1912. Woodcut on heavy cream wove paper. Signed, lower right, and titled, lower left. Inscribed "Weihnachten 1937" (Christmas 1937), lower right margin. 12 3/4" x 8 7/8" (32.2 x 22.7 cm). From an edition of between 20 and 30 impressions. Schiefler/Mosel H 110.

![]()

54. Woman, Man, Servant

1918. Etching on heavy white wove paper. Signed, lower right, and titled, lower margin. 10 3/8" x 8 5/8" (26.2 x 21.9 cm). One of 18 impressions in this state. Schiefler/Mosel 192/I.

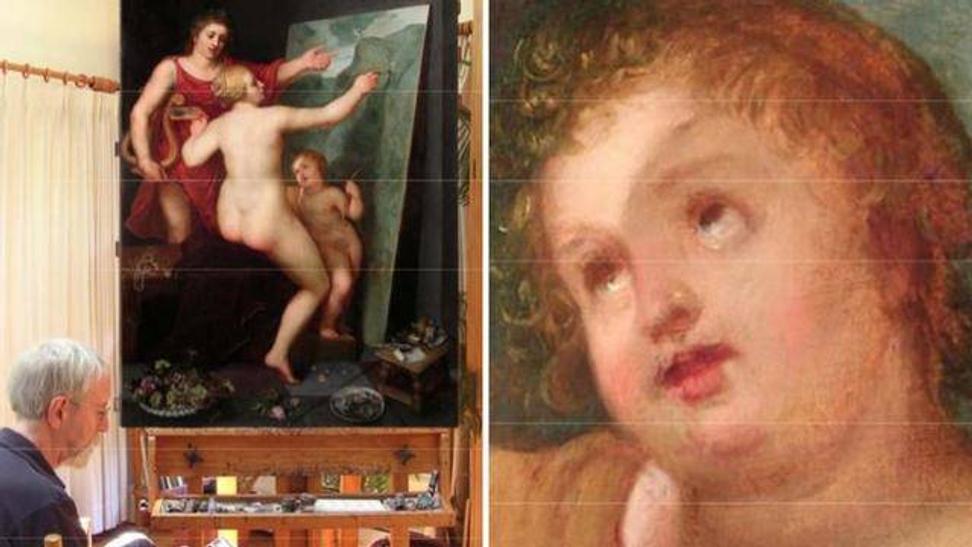

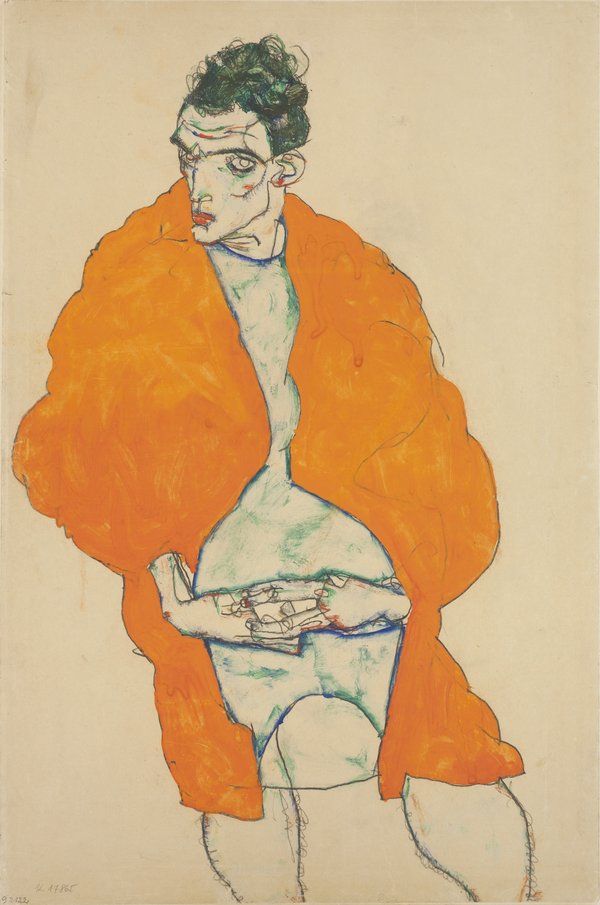

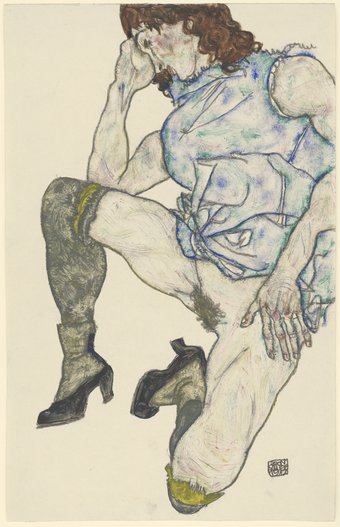

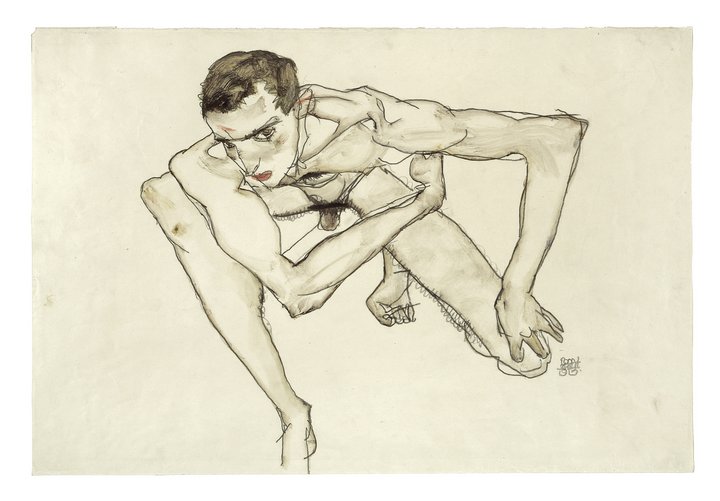

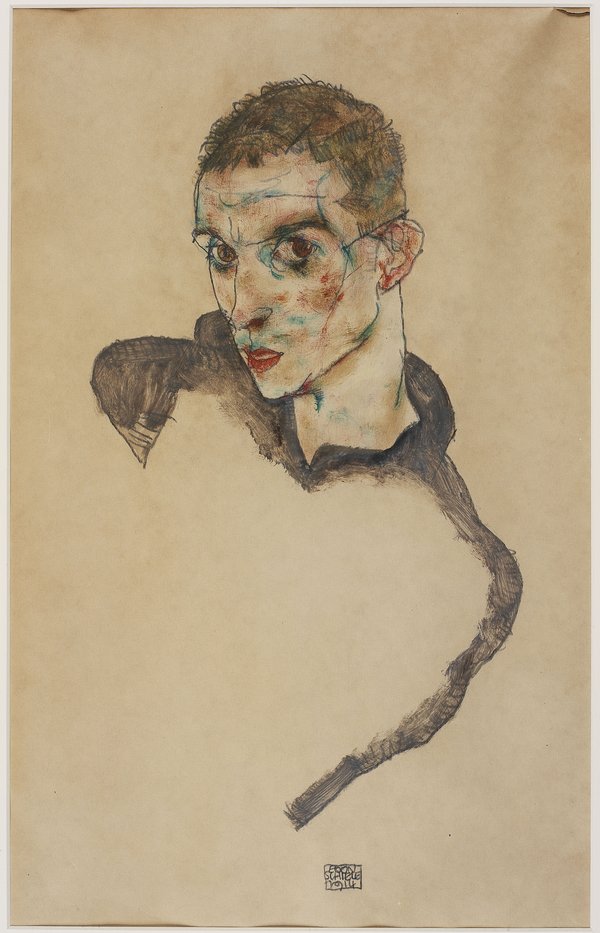

EGON SCHIELE (Austrian, 1890-1918)

![]()

60. Two Peasant Women

1908. Colored crayon on heavy brown wove paper. Initialed and dated, lower left. Inscribed "Hirschbergen 1908," verso. 6 3/4" x 7 7/8" (17.1 x 20 cm). Kallir D. 246a.

61. Baby

1910. Pencil on tan wove paper. Initialed "S" and dated, lower right. 22" x 14 1/2" (55.9 x 36.8 cm). Kallir D. 392.

![]()

63. Study for a Never-Executed Painting

1912. Watercolor, gouache and pencil o heavy cream graph paper. Initialed and dated, lower left. 8 1/4" x 11 3/4" (20.8 x 29.7 cm). Kallir D. 1193. Private collection.

![]()

65. Poster for the 49th Secession Exhibition

1918. Lithograph in black, yellow, and reddish brown on thin yellowish poster paper. 26 3/4" x 21" (67.9 x 53.3 cm). Kallir G. 15/b.

.

32. Archer in Moritzburg (Erich Heckel)

32. Archer in Moritzburg (Erich Heckel)

.

.

%2B57.8%2Bx%2B206.7%2Bcm%2BCedar%2BRapids%2BMuseum%2Bof%2BArt%2C%2BIowa.jpg)