Florence! at the Art and Exhibition Hall in Bonn

22 November 2013 – 9 March 2014

Florence has an extraordinarily rich cultural heritage. Over the centuries, philosophers, writers, architects, engineers, painters and sculptors have embellished the city on the Arno with countless masterpieces. Florence is the city of Dante and Boccaccio, of Donatello and Sandro Botticelli, of Amerigo Vespucci and Macchiavelli and the home of the Medici.

Florence! at the Art and Exhibition Hall in Bonn is the first comprehensive exhibition devoted to the city to be shown in Germany. It takes a closer look at the Tuscan capital and its ‘wonderful Florentine spirit’ (Jacob Burckhardt) that have fascinated visitors for centuries. Florence! presents a portrait of the city and traces its changing roles: from the financial and mercantile powerhouse of the Middle Ages, to the hub of art and science in the fifteenth and sixteenth century and its significance as an intellectual and cosmopolitan centre in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century.

The exhibition showcases the city immortalised by the great artists and scientists of the Renaissance. At the same time, it sheds light on a less well-known, but no less fascinating Florence: a dynamic, ever-changing urban space, home to priceless collections of rare objects from all over the world, cradle of new artistic techniques, a city whose present is forged from the ferment of myth and tradition. Florence! focuses not only on the city’s legendary cultural achievements but also on economic, political and religious developments. A selection of outstanding paintings, sculptures, drawings, textiles, written documents and decorative objects draws a picture of Florence as a laboratory of art and science. These masterpieces present the built, the painted and the written city. Everchanging, Florence is a work of art in its own right.

Subdivided into five main sections, the exhibition takes visitors on a chronological journey through Florence and its history. Each section begins with an introduction to the urban space of the period under examination. Maps and topographical views conjure an image of the city at specific points in time. The growth, development and transformation of Florence through the centuries form the central theme of the exhibition. The exhibition opens with Domenico di Michelino’s idealised view of Florence that unites the city with a portrait of one of its most illustrious sons, the poet Dante Alighieri. Dante and the reception of his work through the centuries constitute a recurring motif throughout the exhibition.

A selection of exquisite drawings, displayed in a cabinet of their own, pays homage to the Florentine culture of draughtsmanship and disegno. Florence! is complemented by a virtual reconstruction of the architectural history of the Florentine cathedral, with special emphasis on the construction of the vast dome, and by a film about ‘Florence, the City of Stone’. Presenting some 350 outstanding objects, the exhibition draws on loans from 45 institutions in and around Florence and from another 25 museums and galleries in Europe and the USA.

An exhibition of the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany in cooperation with the Soprintendenza Speciale per il Patrimonio Storico, Artistico ed Etnoantropologico e per il Polo Museale della città di Firenze and the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz Max-Planck-Institut.

More on the exhibition

The Medieval City

In the early twelfth century Florence attained political autonomy. Having conquered the surrounding territory, the city won access to markets and trade routes. Banking and the textile industry were the cornerstones of the burgeoning Florentine economy in the thirteenth century. Trade connected medieval Florence with other commercial hubs as far away as Asia, and Florentine traders were active in all the big markets. Merchants, bankers and artisans were organised in guilds, and from 1282 the city was governed by the Priorate, a body of representatives of the most powerful of the guilds.

Around 1300 Florence probably had almost 100,000 inhabitants. It was one of the largest cities in Europe and a leading economic power. But the Florentine Republic was forever torn by internal political strife. In the early thirteenth century the tensions between Guelphs and Ghibellines, the factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor respectively, erupted into open conflict. Later, clashes flared up between the wealthy, influential professionals (popolo grasso) and the craftsmen and labourers who were barred from forming guilds (popolo minuto). The fourteenth century was punctuated by some of the worst crises in the history of the city – natural disasters, the collapse of banks, wars, political defeats and the devastating plague epidemic of 1348 – but it was also a period of great innovation in painting and literature. Giotto created a new pictorial language and the poets Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio laid the foundation for a new vernacular literature.

The Renaissance City

At the end of the fourteenth century political stability and prosperity returned to Florence. The conquest of Pisa and its seaport in 1406 gave Florence access to the sea and allowed Florentine trade to reach new heights. It was against this background that the city emerged as the cradle of the innovations that define the Renaissance. Building on the foundations of the study of classical literature and philosophy, Florentine Humanism formulated new ethical and political ideals. This coincided with the artistic re-invention and re-articulation of pictorial space, primarily through the invention of single-point perspective (1410), and with the rediscovery of portraiture, monumental bronzes and the close observation of nature. The most important works of art of the period were the result of co-operations between outstanding artists and prosperous connoisseur patrons, religious orders, families or guilds.

Although fifteenth-century Florence was nominally still a republic, governed by a body of Lord Priors chosen from among its eligible citizens, by 1434 the Medici effectively controlled the government and, with it, the fate of the city. As wealthy patrons of art and science, they were instrumental in shaping the way Florence perceived itself and the way it was perceived from outside. The Renaissance was also a period of political, social and religious tension which found expression in the Pazzi conspiracy (1478) and in the rule and eventual execution of the Dominican friar Savonarola (1494–98).

Florence and the Tradition of Disegno

In the Renaissance drawings were not only seen as the foundation of all artistic endeavour – as a medium of studies and preparatory sketches – they were also appreciated as works of art in their own right and attracted a growing market of connoisseur collectors. In the mid-sixteenth century Florence emerged as the centre of the theoretical debate about the concept of disegno. In Italian the term does not only mean drawing, it also encompasses ‘the animating principle of all creative processes’ (Vasari).

In 1563 Cosimo I founded the first academy, the Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno, which brought together painters, sculptors and architects. This was an important step in Cosimo I’s art politics. In addition to representational purposes, the academy served to protect artists, to safeguard the quality of their training and to establish norms of artistic practice. Giorgio Vasari, the first director of the academy, promoted the primacy of disegno as the guiding and unifying principle of the three artistic disciplines of painting, sculpture and architecture. Disegno became the basis of the nascent canon of the fine arts. Drawings and prints were collected together and laid the foundation for the formation of the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, one of the world’s most important collections of works on paper.

The Medici: The Grand Duchy

By the beginning of the sixteenth century the era of the Florentine Republic had definitely come to an end. In 1530 Emperor Charles V installed Alessandro de’ Medici as the first Duke of Florence. He was succeeded in 1537 by the eighteenyear- old Cosimo, a scion of the cadet branch of the Medici family. Cosimo I is widely regarded as the creator of the Tuscan state. He succeeded in safeguarding the independence of Florence, in conquering the Republic of Siena and, with it, southern Tuscany, and, finally, in being created Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1569. He established himself as an absolutist ruler, retaining the principal offices of the state, while the real power lay with the duke and his privy council, the Pratica secreta. The history of the city was rewritten in a dynastic and monarchist key. Under Cosimo and his sons, Francesco and Ferdinand, Florence became a true princely residence. The city was famous for its lavish celebrations, the rich Medicean collections of objects from all over the world and Galleria dei Lavori, founded in 1588, the first workshop to work exclusively for the court. Politically and economically, however, Florence suffered a gradual but inexorable decline. In the seventeenth century the Medici could no longer stem the downward spiral. Beset with internal political problems, the Grand Duchy suffered severe famines and plague epidemics.

Towards a Modern State

With the death of Gian Gastone de’ Medici in 1737 the male line of the Medici became extinct, and Tuscany passed to Francis Stephen, Duke of Lorraine and later Emperor Francis I. Under the House of Habsburg-Lorraine the backward Tuscan grand duchy of the Medici was modernised and transformed into a model state in the spirit of the Enlightenment. Grand Duke Peter Leopold (1765– 1790) pursued enlightened reform policies of exceptional ambition and reach. Instead of commissioning spectacular buildings and works of art, he sought to improve the living conditions of his Tuscan subjects. Among his most important reforms were the modernisation of the administration, the development of a better network of roads, the curtailment of the Inquisition and of the censorship of the Church, the dissolution of the old guild structures and – unprecedented at the time – the abolition of torture and capital punishment in 1786. Schools, hospitals, libraries and theatres were built in Florence and other cities in Tuscany. Peter Leopold’s art policies were equally innovative and unfailingly dictated by a concern for functionality and usefulness. The Uffizi were reorganised and opened to the public. A few years later the Florentine Science museums were founded. Florence became a destination for tourists on educational journeys and an international city with a flourishing salon culture.

Between Myth and Modernity

In the nineteenth century Florence was an international city and a destination for tourists on educational journeys. Particularly during the period of the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification, Florence was celebrated as the intellectual centre of Italy. In 1865, when Tuscany was incorporated into the newly established Kingdom of Italy, Florence briefly became the national capital.

The episode resulted in radical changes to the urban fabric, among them the construction of new ring roads and residential quarters, but also the ruthless demolition of the medieval city centre. At the same time, the modernisation went in hand with an enormous enthusiasm for all things medieval. And it is in painting that the near-mythical Middle Ages and modernity, the two facets of the city, are most clearly reflected. While traditional academic painters celebrated the idealised era of the city republic, the Macchiaioli gave rise to the only truly revolutionary artistic movement to have emerged in Novecento Italy.

In the late nineteenth century Florence was a city of international collectors and art dealers, who founded new museums, but also contributed to the large-scale exodus of Florentine art and the formation of first-rate collections outside Italy. Florence was home to an international set of artists, writers and scholars. Inspired by their enthusiasm for Renaissance art and culture, they created an image of Florence that continues to influence the way we see the city today

.

Catalogue

FLORENZ!

Format: 24,5 x 28 cm, Hardcover

Pages: 384 with 450 colour illustrations

Trade edition: Hirmer

ISBN: 978-3-7774-2089-9 (German)

Texts by H. Baader, C. Barteleit, A. Giusti, Ph. Helas, W.-D. Löhr, V. Reinhardt,

J. Renn, B. Roeck, E. Spalletti, C. Tauber, T. Verdon and G. Wolf

Images and Credits:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Domenico di Michelino The Allegory of the Divine Comedy, 1465 Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore Archivio storico e fototeca, Firenze

THE MEDIEVAL CITY

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Andrea Pisano and collaborators Weaving 1334–36 Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore Archivio storico e fototeca, Firenze

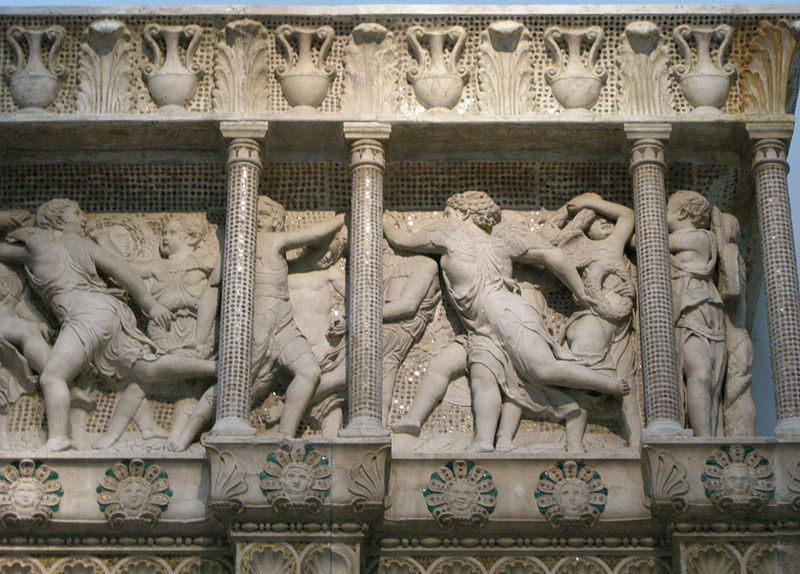

THE RENAISSANCE CITY

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Sandro Botticelli Minerva and the Centaur End of 1480ies Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence© 2013. Foto Scala, Florence – courtesy of Ministero Beni e Attività Culturali

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Donatello Head from the Cantoria 1433–38, Bronze Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence © Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore Archivio storico e fototeca, Firenze

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Masaccio (Tommaso di ser Giovanni di Mone Cassai) San Giovenale Triptych 1422_Museo Masaccio d’Arte Sacra,_Cascia di Reggello_

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Studies for a monumental wall tomb 1525/26 The British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Michelangelo Buonarroti The Medici tombs in the New Sacristy 1520/21 Black chalk on paper The British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Domenico Ghirlandaio and workshop Saint Peter Martyr 1490-98 Fondazione Magnani Rocca Mamiano_di Traversetolo (Parma)_© 2013. Foto Scala, Florence

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Filippino Lippi Tobias and the Angel 1475/80 Oil and tempera (?) on wood © Washington, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Filippino Lippi Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Angels (“Tondo Corsini”) ca. 1481–1482 Collection Ente Cassa di Risparmio, Florence

THE MEDICI: THE GRAND DUCHY

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Agnolo Bronzino Eleonora von Toledo um 1543 Národni Gallerí, Prag © National Gallery in Prague 2013

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Benvenuto Cellini Perseus with Medusa’s Head c. 1553 Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence © 2013. Foto Scala, Florence – _courtesy of Ministero Beni e Attività Culturali

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Benvenuto Cellini Design for the seal of the Accademia del Disegno 1562/64_Black chalk, ink and wash on paper © London, British Museum

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Giovanni Antonio de‘ RossiCameo showing the family of Cosimo I.1558–1562_Florence, Museo degli Argenti_© S.S.P.S.A.E. e per il Polo Museale della città di Firenze – Gabinetto Fotografico