Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Retrospective

23 April to 25 July 2010 Städel Museum, Exhibition House

Also see Kirchner and the Berlin Street and

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938), founding member of the artist association “Brücke” (Bridge) and one of the most significant artists of Expressionism, had a lasting influence on the art of classic Modernism. The oeuvre of the painter, commercial artist and sculptor is being honored by the Städel Museum with the first comprehensive retrospective in Germany for 30 years, featuring over 180 works. “I am amazed at the power of my paintings in the Städel,” Kirchner wrote in his diary on 21 December 1925. Kirchner had close relations to both the Städel and Frankfurt. Not only was the Frankfurt Galerie Schames the venue in 1916 for one of the first Kirchner exhibitions, the Städel was also one of the first museums to buy paintings by Kirchner as early as 1919.

Drawing on its very own Kirchner collection which, with numerous major works, numbers amongst the most significant worldwide, and thanks to high-quality international loans the exhibition was able to present works from all the artist’s periods. Alongside masterworks from the Brücke era with its nudes, the works from his years in Berlin with the famous street scenes, the paintings shaped by World War I that reflect Kirchner’s existential fears, and the Davos works depicting subjects from the Swiss mountains, the less well known work from the artist’s early and late period is also presented. For the first time the works that attracted such controversy executed during his late period in the “new style”, which startle the viewer with their uncompromising twodimensionality and a high degree of abstraction will be on view in Frankfurt together with his major works. The retrospective in the Städel Museum enables a new perspective of the startling modernity of Kirchner, whose excessive lifestyle was reflected in his art in an incomparable manner.

The chronologically arranged exhibition started with a group of important self-portraits providing an overview of the artist’s various stages of life. Born 1880 in Aschaffenburg, in 1938 the artist took his own life in Frauenkirch-Wildboden near Davos. The very large scope of styles evident in his work in itself suggests that Kirchner was much more than “only” an Expressionist.

The next section of the exhibition was devoted to Kirchner’s early work, which shows him to be trying to find himself as an artist. He selects elements from Impressionism, Symbolism and Fauvism. Van Gogh, Henri Matisse and Edvard Munch are important points of reference. While in Kirchner’s painting

“Fehmarn Houses” from 1908

there is evidence of a post- Impressionist style influenced by van Gogh, he later became acquainted with works by Matisse in 1909, in many paintings the prevailing element is the innovative force of the emphasized two-dimensional. The influence of the French master is also clearly manifested in the painting

“Reclining Woman in White Chemise” from 1909

from the Städel collection, which was presented to the public for the first time in this exhibition. As it is on the rear side of the painting “Nude Female at the Window” from the year 1922/23 it was previously considered to be of little importance. It is one of the particular features of Kirchner’s work that he paints on both sides of the canvas. “I, too, have to make some economies now, and material has become very expensive. But thank God, a canvas has two sides,” the artist wrote in 1919. Owing to the fact that Kirchner did not “restore” as he called it, or re-work the rear side, something that frequently occurred, “Reclining Woman in White Chemise” is one of the few large-format early works preserved in its original state. The fact that it is signed also indicates that it can be seen as a finished work.

The third part of the exhibition focuses on Kirchner’s Expressionist works from his Dresden years. During this period Kirchner became a leading figure in the artist group “Brücke” established 1905 in Dresden, which succeeded within a few years in joining the league of the international avant-garde and exert a lasting influence on the image of Expressionism in Germany with its sensual-impulsive painting that has continued until today. In the conservative-academic art business of Germany under Wilhelm II not only the expressive colors and compositions with distorted perspectives had a provocative effect, but also the unconventional, anti-bourgeois style of living and working favored by the artist group, which was committed to the ideal of a sensual harmony of life and artistic activity. They met up in their studios to work free of social constraints and shared these studios in the same way that they shared their models, who were frequently also their respective partners.

A highlight of this creative phase is the painting

“Standing Nude with Hat” (Städel Museum)

for which, according to Kirchner, he was inspired by the painting

“Venus” by Lucas Cranach the Elder (also in the Städel).

In the tableau Kirchner presents his then girlfriend Dodo naked – and yet self-confident and chic. Alongside Dodo the portrayals of the eight year old Fränzi and the somewhat older Marcella, two of the children who regularly visited Kirchner’s studio, also played an outstanding role. This exhibition also featured portraits and nudes of the two girls, some originally from the Brücke Museum Berlin and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. These portrayals form a link to the circus and varieté subjects, which stand out for their exotic quality and lively display of color.

For the first time since 1980s the large-format main work

“Girl Circus Rider” from Saint Louis Art Museum

was shown in Europe again in the Frankfurt retrospective.

The topic of dance as an element of movement, as it is presented, say, in

“Varieté” (Städel Museum)

interested Kirchner throughout his lifetime and also features in his late work.

The move from Dresden to Berlin in 1911 meant a break for Kirchner: The new surroundings not only influenced the subjects in his work but also their style. He expressed the nervousness of the pulsating city with angular, pointed shapes, over-long bodies and bilious, wan colors. The relationships between the sexes are charged. Latent aggressive encounters between whores and clients replace the peaceful mood of the Dresden nudes. Kirchner transferred this clash in his street scenes to the public domain. Today, these paintings are still widely considered as the culmination of his oeuvre.

A highlight of the Berlin years shown in the exhibition – alongside a room featuring street scenes - nudes such as

“The Toilette; Woman before the Mirror” (Centre Pompidou, Paris)

or the work “Two Yellow Nudes with Bouquet of Flowers” (Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur) –

(left)

(center)

(right)

was the monumental triptych “Women Bathing” measuring ca. 196 x 350 cm.

This was the first time since Kirchner’s death that the triptych could be secured for an exhibition and shown together with loans from private collectors, the Kirchner Museum Davos and the National Gallery Washington. Kirchner himself describes it as one of his strongest works.

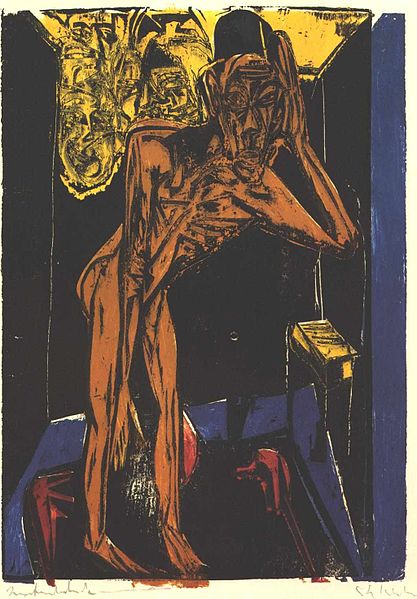

The artistically fertile era of the Berlin years experienced a deep cut through the outbreak of World War I. Kirchner responded to the awful reality of war with dread and inner conflict. He featured his own experiences and the existential fear he felt during his military service in paintings such as

“Artillerymen in the Shower” (Guggenheim Museum, New York)

or in the series of wood engravings on

“Pictures for Chamisso’s Peter Schlemih” (Städel Museum),

one of the most important prints of the 20th century.

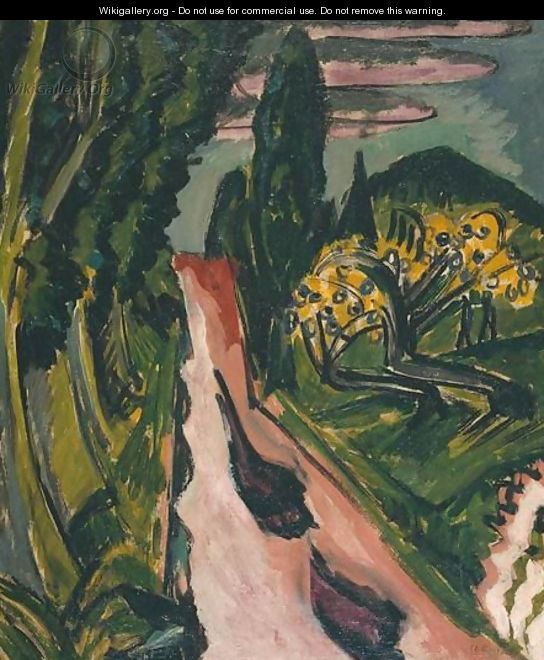

Following emotional and physical collapses Kirchner recuperated in a sanatorium in Königsstein im Taunus. Works such as

“West Harbor, Frankfurt” (Städel Museum) or

“Taunus Road“ (private collection)

were produced in this period.

Kirchner would also find important sponsors of his work in Frankfurt: Not only his gallery owner Ludwig Schames, but also some of his most important collectors lived here. They included the chemist Carl Hagemann, whose collection of contemporary art was one of the most comprehensive at the time. The Städel largely owes the Kirchner works it owns to this collection, which was made over to the Museum after World War II by Hagemann’s heirs as a gift or permanent loan.

Broken by his experiences of the war Kirchner went to Davos in 1917 to recuperate and remained there until his death in 1938. Originally intended as a place of temporary retreat the Swiss Alps rapidly became an important source of artistic inspiration. The artistic challenge was no longer posed by the pulsating city but the majestic landscape of the mountains and the peasant life he experienced there.

The final section of the exhibition explores Kirchner’s “new style” developed from the mid-1920s. A completely transformed color palette of pink, brown and lilac tones made demands on the observer’s aesthetic perception. What is remarkable is that as in his early work the artist was inspired primarily by French art. The curved forms and geometrically abstract figures frequently recall Picasso. Kirchner’s renewed change of style, which he himself always regarded as an advancement met with little understanding amongst his supporters. Even today critics and public occasionally respond with irritation at this “post-Expressionist” work phase.

Kirchner experienced the most vehement attack on his art in 1937, as a result of the National Socialists banning what they considered to be “degenerate art”: more than 600 works by Kirchner were removed from German museums. The Städel also lost all of its Kirchner works at the time. Since the mid-1930s the artist’s physical condition had deteriorated once again. Kirchner was again consuming substantial amounts of tranquilizers, also because of his increasing depressions. In March 1938 when the German army marched into Austria and stood just 20 kilometers away from Davos as the crow flies, Kirchner destroyed part of his works – presumably out of fear they might fall into the hands of the Nazis in the event of them occupying Switzerland. On the morning of June 15, 1938 Kirchner put an end to his life close to his home by shooting himself twice in the heart.

Catalogue:

The exhibition was accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue published by Hatje Cantz Verlag and edited by Felix Krämer, which primarily presents more recent positions of research on Kirchner. It features essays by Felix Krämer, Thomas Röske, Karin Schick and Hanna Strzoda and articles by Javier Arnaldo, Nicole Brandmüller, Melanie Damm, Chantal Eschenfelder, Nina Jaenisch, Daniel Koep, Bettina Lange, Sandra Oppmann, Beate Ritter and Nerina Santorius. German and English edition.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Biography

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was a torn, extremely contradictory character, radically and relentlessly demanding of himself. He was an artist, who frequently reinvented himself and who controlled his public image painstakingly. The self-portraits, which predominantly date back to the years of World War I and his time in Davos are an important tool for the construction of his image. While the wartime works show a physically and psychologically weak person, the Swiss works reflect a gradual improvement in his health.

Equally those portraits showing him together with his partner Erna Schilling point towards a change: Initially Erna was his model and muse, in later years, however, she is increasingly recognisable as partner and “companion”. The notion of “twofold entity” is manifest in the increasing similarity of the representation of Erna and Kirchner. In everyday-life, however, there was little sense of equality: Erna had to fully submit to Kirchner and his art.

The early years

In June 1905 while they were registered as students of architecture, Kirchner and his fellow students Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rotluff founded the artists’ group Brücke. Driven by their ambition to renew art against “the established older forces”, in their programme they called for the younger generation “to paint immediate and unadulterated”: New painting no longer sought naturalism in the representation of things. It was important to artistically capture the essence of a theme. Members of the international avant-garde, such as Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch and Henri Matisse, served as inspiration for the Brücke-members in the early stages. Their models also contributed to their style.

Kirchner and his artist colleagues turned against the study of traditional poses performed by professional models, commonly used in the academies. Instead they held sessions at their workshops, where they sketched the natural and unrestrained movements of their partners. Kirchner’s Dresden lover Doris Große was a favourite at this time and after their relationship had finished, the artist continued to consider her an ideal female figure.

The Expressionist in Dresden

Born into a respectable middle-class family, Kirchner was fascinated by the music hall and circus scene. He repeatedly focussed on the movement of danceand artistic performances, much like the play with sensuality and eroticism. Kirchner crafted furniture for his workshop – life and work place at the same time – with which he created an alternative place for free life and sexuality. The art and culture of native peoples in Africa served as ideals. A group of young girls was among the models in Dresden. Fränzi, who met the Brücke when she was eight years old, and Marcella are often portrayed. Nude representations as allegories of an uncivilised world were of particular interest. The artists used the inexperience and innocence of the children, which was the nearest approximation of their idea of unspoilt nature. The girls accompanied the artists on their excursions to the Moritzburg Ponds near Dresden. Here they studied nudes en plein air. The closeness of the artists in life and work at the time was reflected in a common Brücke-style.

The Expressionist in Berlin

Full of expectations Kirchner moved to Berlin in the autumn of 1911. When success was not immediate – the MUIM-Institute, which he and Pechstein had founded only attracted two students – Kirchner deplored the capital as “terribly common”. The dissolution of the Brücke in 1913 further taints his view of his new city.

The pulsating atmosphere of the metropolis nevertheless inspired Kirchner to new subjects and also brought with it a stylistic change. He uses steep perspective, agitated hatching and the glaring colours of city illuminations to capture the clandestine contact of punter and cocotte in Berlin’s streets and squares.

The harmony between the sexes, as portrayed in Dresden, is being replaced by latent aggression. The ideal of beauty is now strongly influenced by the dancer Erna Schilling, whom Kirchner met in 1912. She would be his partner until his death. Together with her, he left behind the hectic of the capital in summer for Fehmarn island, where they sojourned in a paradisiacal parallel world.

War and Breakdown

Once World War I had broken out, Kirchner voluntarily enlisted. He started his basic training in Halle in 1915. This experience is reflected in several of his works. Unsuitable for service, Kirchner suffered a physical and psychological break down after only two months. Repeated sojourns at Dr. Kohnstamm Sanatorium in Königstein followed. From the Taunus Kirchner also travelled to nearby Frankfurt, where he visited his gallerist Ludwig Schames. Other sanatoria he sought cure at were in Berlin and Kreuzlingen.

In spite of his illness Kirchner was highly productive. Landscapes, scenes of life at the sanatorium and intensive portraits of himself and others date from this period. His immense fear of being drafted again – temporarily Kirchner even refused to eat in order to remain unfit for service – ceased only when the war was over.

In the Mountains. First years in Davos

In 1918 Kirchner retired to the Swiss village of Davos, where he would lead a simple and secluded life until his suicide in 1938. Davos would become his second home. Soon Erna would follow him there. The quietude of the Alps resulted in new themes: landscapes and scenes of life of the mountain farmers replaced the glittering demimonde of Berlin. Kirchner’s style became calmer and increasingly flat. Violets, pinks and greens now determined the palette. While he had retired to the remote mountains, Kirchner and his art remained ever present in Germany.

Kirchner kept abreast with the art scene through the press, exchanged letters with art collectors and penned praising reviews of his work under pseudonym. 1925/26 Kirchner returned to Germany for the first time. He visited Frankfurt, Chemnitz, Dresden and Berlin. Many works were inspired by this trip.

The “New Style“

By 1925 the “new Style” marks Kirchner’s gradual departure from his expressive-figurative period. His art is becoming increasingly abstract. The pictorial compositions evolve out of colour-planes, which are frequently outlined by a contour. Kirchner’s play with simplified overlapping shapes seems at odds with his simultaneous attention to detail. This infuses his works with a curious tension.

The artist considered his change of style as the logical development of his oeuvre, a notion which he supported by theory. He further explained, he was seeking no less than the “connection of contemporary German art with the international (sense of) style”. The formal proximity of the “new Style” to the art of key figures of the international avantgarde, first and foremost Pablo Picasso, is striking. In spite of his pursuit of abstraction, Kirchner never excluded figurative elements, which he considered to be the link and thereby the key to the understanding of his art.