From 16 June 2012 to 27 January 2013, the Hermitage Amsterdam presented

Impressionism: Sensation & Inspiration: the world-famous Impressionist paintings from the vast collection of the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, in their artistic context. Masterpieces by pioneers like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Camille Pissarro were accompanied by the work of other influential French painters from the second half of the nineteenth century, such as Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérôme.

The exhibition focused on contrasts between artistic movements. For instance, visitors will see and experience the sensational quality of Impressionism, the movement that heralded a new age. All the paintings, drawings, and sculptures came from the collection of the St. Petersburg Hermitage. Seldom has such a rich survey of this period been on display in the Netherlands.

Sensation

Impressionism derives its name from Monet's painting Impression, soleil levant (1872); the name was first used mockingly by a journalist, but was soon adopted as a badge of pride. These artists rendered their fleeting impressions in vibrant colours for the pure pleasure of painting. They had no use for lofty ideas and worked in the open air under ever-changing light. The Impressionists brought a breath of fresh air to the stuffy art world of their day. Their subjects are easy to appreciate. Along with city scenes and landscapes, they often depicted the most charming aspects of everyday bourgeois life: Paris cafés and boulevards, seaside excursions, informal portraits, and rowing trips just outside town. The revolutionary ideas of this new generation clashed with the reigning academic tradition. Their colourful ‘impressions’ were seen as shocking and radical, and at first they were frequent targets of ridicule. Yet their radical approach to style, technique, and subject matter proved deeply inspiring to many artists. They ushered in a new perspective on reality, a new concept of beauty, a new era.

Inspiration

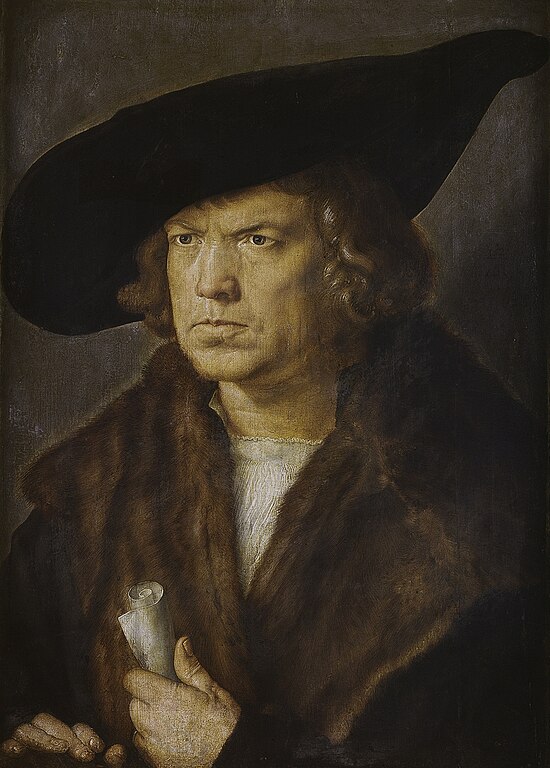

Impressionism began as a response to the classicism of the Paris Salon, an annual exhibition of officially selected art. The exponents of this style painted precisely as artists were expected to paint: carefully staged scenes with crisp outlines and an eye for detail. Their subjects were mythological, historical, or religious. The most prominent artists in the neo-classicist tradition were

![]()

Alexandre Cabanel (1823–89), Portrait of Countess Elizaveta A. Vorontsova-Dashkova [Portrait de la comtesse Élisabeth Vorontsova-Dachkova], 1873. Oil on canvas, 99 х 73 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

and

![]()

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), The Sale of a Female Slave in Ancient Rome, 1884. Oil on canvas, 92 х 74 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

.

One of the best-known French Romantics is

![]()

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Lion Hunt in Morocco [Chasse aux lions au Maroc], 1854. Oil on canvas, 74 x 92 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Painters such as

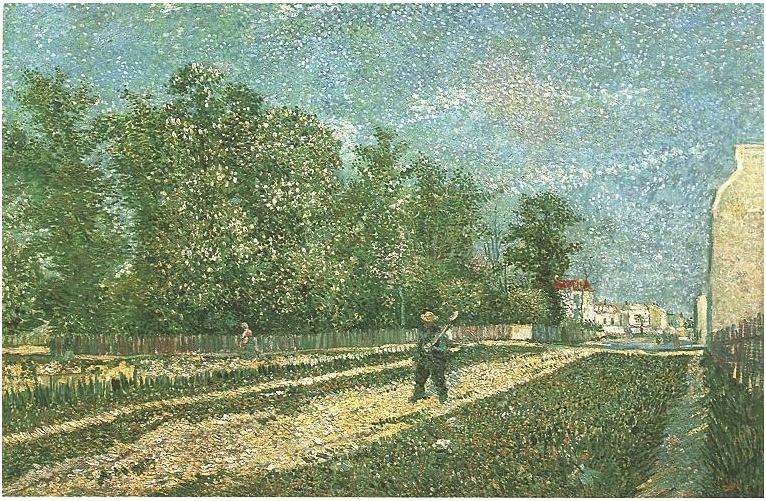

![]()

Théodore Rousseau (

Landscape with a Ploughman, 1860-1865)

and

![]()

Charles-François Daubigny (1817–78),

The Pond [L’Étang], 1858. Oil on canvas, 57.5 x 93.5 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

represent the Barbizon School. They can be seen as forerunners of the Impressionists, because they painted their realistic landscapes in the open air.

The exhibition placed the Impressionists in the company of their predecessors, contemporaries, and successors, including both kindred spirits and competing movements. Favourites like

![]()

Claude Monet (1840–1926), Woman in a Garden [Dame au jardin], 1867. Oil on canvas, 82.3 x 101.5 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

and

![]()

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919),

Portrait of the Actress Jeanne Samary [Portrait de Mlle Jeanne Samary], 1878. Oil on canvas, 174 x 101.5 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

were hung side by side with the work of Delacroix, Daubigny and Gérôme, as well as such magnificent paintings as

![]()

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906),

Smoker [Le fumeur], c. 1890–92. Oil on canvas, 92.5 x 73.5 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

and

![]()

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903),

Eü haere ia oe (Where Are You Going?). Woman Holding a Fruit [Eü haere ia oe (Où vas-tu?). La femme au fruit], 1893. Oil on canvas, 92.5 x 73.5 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

who were inspired by Impressionism to develop wholly original, personal styles.

In short, the Hermitage Amsterdam offered a clear and fascinating overview of the many currents and controversies in the turbulent French art scene between 1850 and 1900.

The visual arts too were going through door spectacular developments in France, although the pace of change was initially slow. Aside from the Romantic school (represented by artists such as Eugène Delacroix), this was also the heyday of Neoclassicism (Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jean-Paul Laurens) and Realism (Jean-Baptiste Corot, Jean François Millet). The artists who had been trained at the leading art academies painted everything exactly as they envisaged it in their imagination. Mythological, Biblical and historical tales and events were the most prestigious subjects. Any artist wanting to establish his name would try to exhibit his work in the annual Salon. This meant submitting it to the scrutiny of the jury, the members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, who applied strict selection criteria. The jury defined what was to be deemed ‘beautiful’, and looked askance at free spirits. The jury could make or break an artist’s career.

Édouard Manet quarrelled on more than one occasion with the Salon jury, which rejected some of his paintings for failure to meet the set criteria. As time went on, the young artists made their protests heard more loudly. In 1863, when over half of the entries were rejected, the situation escalated to the extent that Emperor Napoleon III was obliged to intervene. The result was an alternative exhibition featuring work that had failed to please the jury: the ‘Salon des Refusés’. But many rejected artists declined to take part, reasoning that building up a reputation as an outcast was a poor career move.

Manet did exhibit his paintings at the Salon des Refusés, and his

![]()

Déjeuner sur l’herbe

(which today hangs in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris) provoked an immediate outcry. Visitors were aghast to find themselves face to face with a nude lady – not even a Greek goddess – depicted sitting in a mundane park picnicking with two gentlemen clad in elegant suits, all painted in a multitude of bright dots of colour. The public thought the work a disgrace. Yet this Salon des Refusés became a breeding ground in the Paris art world for a new, ambitious group of painters.

![]()

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Head of a Woman [Tête de femme], c 1876. Oil on canvas, 38.5 x 36 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Fleeting impressions

It was in 1874 that the young renegades made their collective presence felt in public for the first time. Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (who had started his career by painting porcelain tea-cups) organised an exhibition in the studio of the photographer Paul Nadar, in which an amazing 31 painters took part. They included Claude Monet and his teacher Eugène Boudin. Paul Cézanne submitted his House of the Hanged Man. Alfred Sisley was represented with a landscape, and Camille Pissarro with his gardens in Pontoise. Other exhibitors included Berthe Morisot (the only woman) and Georges Seurat. Degas hoped, he wrote in a letter, that they would ‘get a few thousand people to sit up and take notice’.

In this objective, they succeeded gloriously. But they also unleashed a harsh, dismissive response from the critics. The journalist Louis Leroy, after visiting the show, dashed off a scornful review in the daily press. He reserved his most withering remarks for Monet’s Impression, soleil levant (1872): ‘Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape’. He went on to brand Monet and the rest a bunch of ‘impressionists’. The word stuck: the artists themselves soon adopted it as a proud sobriquet. They saw Manet as their primary source of inspiration, although he refused to call his work impressionist.

Most of the visitors left the exhibition in a state of shock, having completely failed to comprehend the style of these painters. The impressionists had sparked a scandal. In their work, it was not the subject they depicted that mattered most, but the fleeting impression of that subject, painted in bright colours, in short, rapid strokes placed alongside each other. The rendering of natural light figured prominently in this approach.

![]()

Claude Monet (1840–1926), Corner of a Garden at Montgeron [Un coin de jardin à Montgeron], 1876. Oil on canvas, 175 x 194 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The Impressionists did not work in stuffy studios like the Salon artists, but went outside and painted in the open air, like the Barbizon painters (whose brown and green landscapes, painted from life, were also turned away by the Salon jury). By this time, painting en plein air had become easier, since tubes of ready-made paint were available, and pre-primed canvases could be purchased, already stretched on timber frames.

New view of the world

The Impressionists’ subjects were also different from those of their predecessors. They took no interest in depicting a Lion hunt (above) such as the one by Delacroix in 1854, or Peasant woman guarding her cow near the woods, painted in 1865-1870 by the Realist Corot.

![]()

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796–1875), Peasant Girl Grazing a Cow at the Forest [Paysanne gardant sa vache a la lisière d'un bois]. 1865–1870. Oil on canvas, 47.5 x 35 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Instead, they painted everyday scenes showing the new bourgeoisie that had been emerged in the industrial revolution: rowing trips and seaside outings, people walking along the banks of the Seine, parading along the boulevard, and enjoying Parisian night life. They were also fascinated by the constant changes of atmosphere in the natural world and the city. For the rest, the impressionists did not seek to convey any message with their work.

Take the painting Woman in the garden by Monet (1867),(above) featured in the exhibition at the Hermitage Amsterdam. It shows a woman, seen from behind. It does not matter who she is; Monet is not interested in conveying her character. Her white dress and parasol do tell us something – about the fashions of the day, for instance. But the atmosphere of this painting is determined mainly by the effect of the sunlight and the sections left in the shade, and the subtle colour distinctions between them. Your first impression is always the most important, say the Impressionists. But we are also struck by the sheer cheerfulness, the carefree beauty – beauty for its own sake. The emphasis was no longer on what was depicted, but on how it was painted. It was a new look at the world.

For a better understanding of the sensation that the Impressionists caused in the late nineteenth century, from our vantage point in 2012 – no simple matter, since today Impressionism is universally accepted and admired – the exhibition in the Hermitage Amsterdam goes back to that time. It returns to the age in which those revolutionary painters first stirred up controversy. That is why, in this exhibition, the impressionist paintings and drawings of Monet, Sisley, Pissarro and Renoir were hung alongside the Salon art of their contemporaries.

![]()

Edmond-Georges Grandjean (1844–1908), View of the Champs-Élysées from the Place de l'Étoile in Paris [L’avenue des Champs- Élysées, vue de la place de l’ Étoile], 1878. Oil on canvas, 85.5 х 136.5 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Look at the more traditional painting View of the Champs-Elysées from the Place de l'Étoile in Paris (1878) by Edmond-Georges Grandjean and compare it to the Impressionist Place du Théâtre Français in Paris (1898) by Pissarro or The River Banks at Saint-Mammès (1884) by Sisley. The differences are immediately obvious. It is the apparent reality versus an impression of the reality. Precision versus the ephemeral.

![]()

Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), Place du Théâtre Français, Paris [Place du Théâtre Français], 1898. Oil on canvas, 65.5 x 81.5 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Alfred Sisley (1839–99), River Banks at Saint-Mammès [Berges de la rivière à Saint-Mammès], 1884. Oil on canvas, 50 x 65 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Or take the Portrait of Countess Elizabeth Vorontsova-Dashkova (1873) by Cabanel,

![]()

Alexandre Cabanel (1823–89), Portrait of Countess Elizaveta A. Vorontsova-Dashkova [Portrait de la comtesse Élisabeth Vorontsova-Dachkova], 1873. Oil on canvas, 99 х 73 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

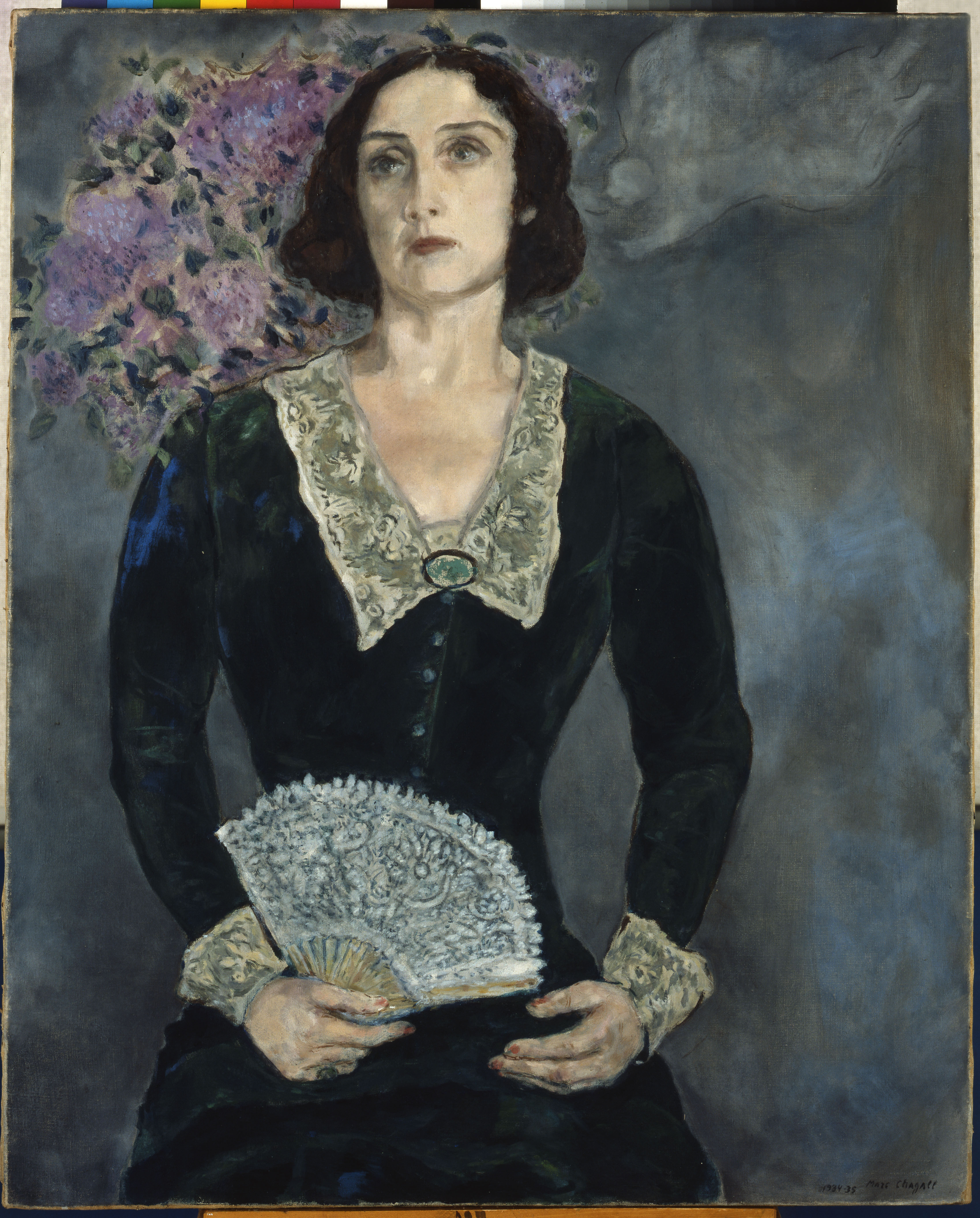

which was eminently acceptable to the Salon jury. This lady needs to be admired from a suitable distance, while Renoir’s

Portrait of the actress Jeanne Samary (1878)

![]()

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919),

Portrait of the Actress Jeanne Samary [Portrait de Mlle Jeanne Samary], 1878. Oil on canvas, 174 x 101.5 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

rather invites viewers to engage the sitter in conversation. The Parisian public keenly felt the tension between the traditional images and the groundbreaking new work, a tension that inevitably led to controversy.

Gallery owner Durand-Ruel

The eventual breakthrough and success of Impressionism were largely thanks to the efforts of the Parisian gallery-owner Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922). He saw something in those paintings that no one else was yet able to see. He purchased them to enable his protégés to carry on working – and to give them something to live on. Reselling them was not always possible, and more than once he was on the verge of bankruptcy. It was not until he opened branches in London, Brussels and New York, and tapped into a new group of collectors, that the Impressionists conquered the world. He was the first gallery owner who succeeded in selling a new ‘school’. ‘Without Durand-Ruel’, said Renoir, generous as ever, ‘we would not have survived and caviar would have been a good deal rarer.’

Among Durand-Ruel’s more important clients were the Russians Mikhail (1870-1903) and Ivan Morozov (1871–1921) and Sergei Shchukin (1854–1936). These fabulously wealthy textile merchants from Moscow bought work by the French Impressionists – Sisley was Morozov’s favourite artist – from a desire to inject new vitality into the art of their own country. They dared to take the rebellious French paintings to Russia and to display them in their own homes so that young Russian artists could see what was happening in Paris, the beating heart of European art. And they could draw inspiration from it. Most of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings that were on view at the museum came from the collections of these two great art lovers.

![]()

Charles-François Daubigny (1817–78), The Pond [L’Étang], 1858. Oil on canvas, 57.5 x 93.5 cm © State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The Impressionists were a source of inspiration for numerous painters. One of them was Dutch – Vincent van Gogh. It is well known that upon arriving in Paris in 1886, Van Gogh immediately fell under the spell of the Impressionists. He made their acquaintance through his brother Theo, who ran an art gallery. It was in their work that he found the sunlight and the colours he had been looking for. In a letter to a friend he wrote: ‘In Antwerp I did not even know what the Impressionists were, now I have seen them and . . . I have much admired certain Impressionist pictures.’ He incorporated their ideas and techniques into his work in an entirely individual fashion.

More images from the exhibition:

![]()

Jean-Paul Laurens (1838–1921), Emperor Maximilian of Mexico before his Execution [L’empereur Maximilien du Mexique avant son exécution], 1882. Oil on canvas, 224.5 x 302.5 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Girl with a Fan [Jeune femme à l’éventail], 1880. Oil on canvas, 65 x 50 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Claude Monet (1840–1926), Meadows at Giverny [Les prairies à Giverny], 1888. Oil on canvas, 92.5 x 81.5 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Benjamin Constant (1845–1902), Portrait of Mrs Marina S. Derwis [Portrait de Mme Marina Sergeievna von Derwis], c 1899. Oil on canvas, 133.5 х 100 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Alphonse Marie de Neuville (Deneuville, 1835–85), Street in an Old Town [Rue de la vieille ville], 1873. Oil on panel, 51 х 34.5 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Alphonse Marie de Neuville (Deneuville, 1835–1885), Champigny (een zolder in Champigny, 2 december 1870) [Champigny (Le grenier à Champigny le 2 décembre 1870)], 1875. Olieverf op doek, 51 х 74,5 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Eugène Fromentin (1820–76), Thieves in the Night [Voleurs de nuit], 1868. Oil on canvas, 115 х 167 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Child with a Whip [Enfant au fouet], 1885. Oil on canvas, 105 x 75 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Banks of the Marne [Les bords de la Marne], 1888–90. Oil on canvas, 65.5 x 81.3 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

![]()

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Fatata Te Moua (At the Foot of a Mountain) [Fatata te Mouà (Au pied de la montagne)], 1892. Oil on canvas, 68 x 92 cm

© State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

.jpg!Large.jpg)

/Selfportrait_Monkeys.jpg)

/Frida_as_Tehuana.jpg)

/Selfportrait_Necklace.jpg)

/Frida_Kahlo_on_the_bed.jpg)

/frida_Kahlo_the_Bride.jpg)

/Frida_with_selfportrait.jpg)

/FridaKahlo_with_flowers.jpg)

/Frida_Kahlo_with_idol.jpg)

,_1899%E2%80%931900_monotype.jpg)

_(1).jpg)

_Christus_gewidmet,_oil_on_canvas,_174.6_x_192.4_cm,_Museum_of_Modern_Art,_New_York.jpg)

_1862.jpg/235px-Whistler_James_Symphony_in_White_no_1_(The_White_Girl)_1862.jpg)

,_John_Singer_Sargent,_1884_(unfree_frame_crop).jpg/300px-Madame_X_(Madame_Pierre_Gautreau),_John_Singer_Sargent,_1884_(unfree_frame_crop).jpg)