Few artists have captured the public’s imagination with the force of Frida Kahlo (1907–1954). In celebration of the 100th anniversary of the birth of this Mexican artist and to recognize her powerful influence on artists working today, the Walker Art Center (in association with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) organized a major traveling exhibition that went beyond the myth, providing an intimate look at 46 of Kahlo’s hauntingly beautiful paintings and 90 photographs from her personal albums, many of which had never been seen by the public. Premiering at the Walker October 27, 2007 to January 20,2008 and co-curated by world-renowned Kahlo biographer and art historian Hayden Herrera and Walker associate curator Elizabeth Carpenter, the exhibition was on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, February 20–May 18, 2008 and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California, June 14–September 28, 2008.

While concentrating on Kahlo's hauntingly seductive and often brutal self-portraits, the exhibition also will include those particular portraits and still-life paintings that amplify her sense of identity. The peculiar tension between the intimacy of Kahlo's subject matter and the reserve of her public persona gives her self-portraits the impact of icons. As her practice progressed, her images grew in confidence and complexity, reflecting her private obsessions and political concerns. Kahlo struggled to gain visibility and recognition both as a woman and an artist, and she was a central player in the political and artistic revolutions occurring throughout the world.

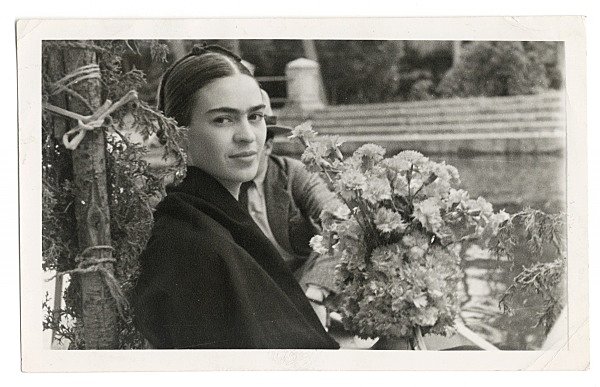

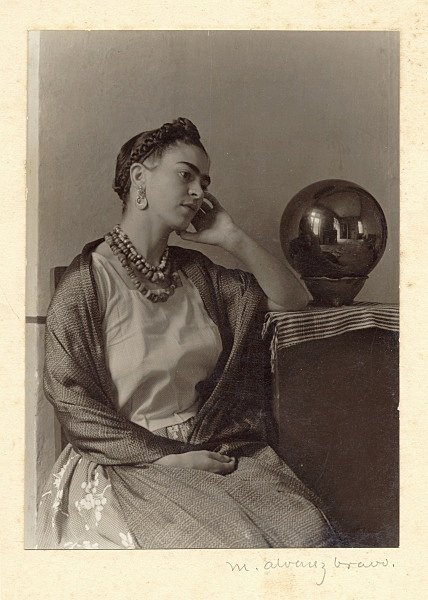

The exhibition also featured photographs that once belonged to Kahlo and Diego Rivera from the Vicente Wolf Photography Collection, many of which had never before been published or exhibited. Emblematic images of Kahlo and Rivera by preeminent photographers of the period (Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Lola Alvarez Bravo, Gisele Freund, Tina Modotti, Nickolas Muray) were on view alongside never-before-seen personal snapshots of the artist with family and friends, including such cultural and political luminaries as André Breton and Leon Trotsky. These photographs—several of which Kahlo hand-inscribed with dedications; effaced with self-deprecating marks; and kissed, leaving a trace of lipstick—pose fascinating questions about an artist who was both the consummate manufacturer of her own image and a beguiling and willing photographic subject.

During her lifetime, Kahlo was best known as the flamboyant wife of renowned muralist Rivera. Today she has become one of the most celebrated and revered artists in the world. Between 1926, when she began to paint while recuperating from a near-fatal bus accident, and 1954, when she died at age 47, Kahlo painted some 66 self-portraits and about 80 paintings of other subjects, mostly still lifes and portraits of friends. "I paint my own reality," she said. "The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to." Her reality and her need to explore and confirm it by depicting her own image have given us some of the most powerful and original images of the 20th century. Paradoxically, her work allowed her to both express and continually fabricate her own subjectivity.

Kahlo was born in 1907 in Coyoacán, then a southern suburb of Mexico City. Three years after the 1925 bus accident, she showed her paintings to Rivera. He admired the paintings, and the painter, and a year later they married. Theirs was a tumultuous relationship: Rivera once declared himself to be "unfit for fidelity," and Kahlo largely withstood his promiscuity. As if to assuage her pain, Kahlo recorded the vicissitudes of her marriage in paint. She also recorded the misery of her deteriorating health—the orthopedic corsets she was forced to wear, the numerous spinal surgeries, plus a number of miscarriages and therapeutic abortions. Her painful subject matter is distanced by an intentional primitivism, as well as by the canvases' small scale. Kahlo's sometimes grueling imagery is also mitigated by her sardonic humor and extraordinary imagination. Her sense of fantasy, fed by Mexican popular art and pre-Columbian culture, was noted by surrealist poet and essayist Breton when he came to Mexico in 1938 and claimed Kahlo for Surrealism. She rejected the designation but clearly understood that doors would open under the surrealist label—and they did: Breton helped secure exhibitions for her in New York in 1938 and Paris in 1939.

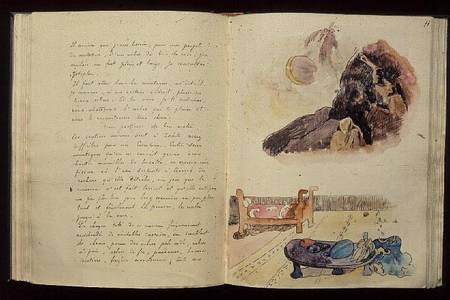

Soon after Kahlo returned from attending her Paris show, Rivera asked her for a divorce. They remarried a year later. In the second half of the 1940s Kahlo's health worsened; she was hospitalized for a year between 1950 and 1951, and in 1953 her right leg was amputated at the knee due to gangrene. Her insistence on being strong and joyful in the face of pain sustained her, however; she drew a picture of her severed limb in her journal and wrote, "Feet, what do I need them for if I have wings to fly?"

Kahlo had her first exhibition in Mexico in 1953. Defying doctor's orders, she attended the opening and received guests while reclining on her own four-poster bed. Because she could not sit up for long and she suffered severe effects from prescribed painkillers, her paintings in the period from 1952 to 1954 lost the jewel-like refinement of her earlier works. Her late still lifes and self-portraits—many of which proclaim Kahlo's allegiance to Communist doctrine—testify to her passion for life and her indomitable will, however.

Frida Kahlo brought together works such as

Henry Ford Hospital (1932),

depicting the artist's miscarriage in Detroit (a first in terms of the iconography of Western art history), and

The Broken Column (1944), painted after she underwent spinal surgery.

It also included self-portraits such as

Me and My Doll (1937)

and Self-Portrait with Monkeys (1943),

both of which explore the theme of childlessness.

The artist's suffering over Rivera's betrayals is reflected in paintings like her masterful double-portrait

The Two Fridas (1939);

created during her separation and divorce from Rivera, the work presents a powerful depiction of pain inflicted by love and Kahlo's divided sense of self.

Collectively, these images suggest the extent to which, for Kahlo, painting served as catharsis, as well as an opportunity to redefine and critique modern bourgeois society.

Collectors of Kahlo's work can be found around the world—the paintings in the exhibition come from some 30 private and institutional collections in France, Japan, Mexico, and the United States. Several paintings have never before been on public view in the United States. Two of the most important and extensive collections of Kahlo's work—the Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño Collection in Mexico City and the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of Modern and Contemporary Mexican Art, currently housed in the Centro Cultural Muros in Cuernavaca—have loaned some of their most treasured Kahlo paintings to the exhibition.

The exhibition was accompanied by a richly illustrated 304-page catalogue featuring more than 100 color plates, as well as critical essays by Herrera, exhibition co-curator Elizabeth Carpenter, and Latin American art curator and critic Victor Zamudio-Taylor. A separate plate section is devoted to works from the Vicente Wolf Photography Collection. The catalogue also includes an extensive illustrated timeline of relevant socio-political world events, artistic and cultural developments, and significant personal experiences that took place during Kahlo's lifetime, along with a selected bibliography, exhibition history, and index.

Frida Kahlo was organized by the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, in association with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition was co-curated by Hayden Herrera and Walker Art Center Associate Curator Elizabeth Carpenter.

More images from the exhibition:

Frida Kahlo, The Frame, circa 1938

oil on aluminum and glass_11-1/4 x 8-1/8 inches unframed_12-11/16 x 9-5/8 inches framed

Collection Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Photographer unknown, Diego Rivera, Cuernavaca, 1930

Vicente Wolf Photography Collection

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (Autorretrato con collar de espinas y colibrí), 1940

oil on canvas_24-5/8 x 18-7/8 inches_Nikolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin

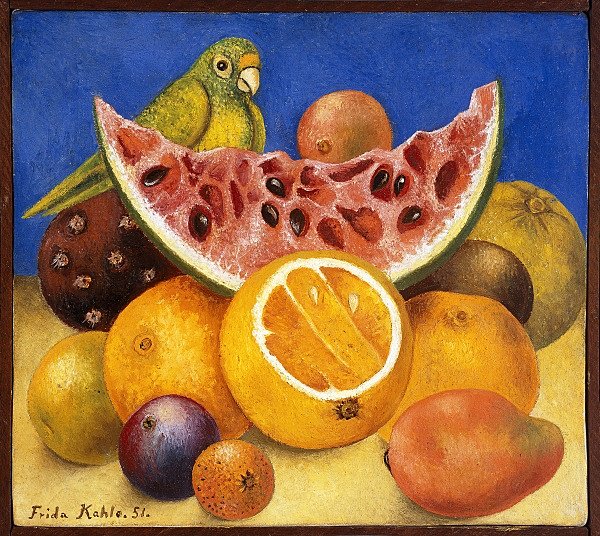

Frida Kahlo, Still Life with Parrot and Fruit (Naturaleza muerta con loro y frutas), 1951

oil on canvas_9-7/8 x 11-1/16 inches_Nikolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Lola Alvarez Bravo, Frida Kahlo with 1930 Self-Portrait drawing by Diego Rivera, Coyoacan, circa 1945

Vicente Wolf Photography Collection

© 1995 Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona Foundation

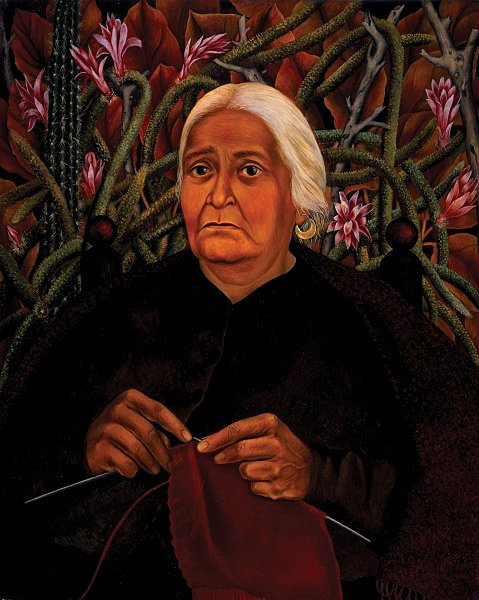

Frida Kahlo, Portrait of Doña Rosita Morillo (Retrato de Doña Rosita Morillo), 1944

oil on Masonite_30-1/16 x 24 inches unframed_39-3/8 x 33 x 2-3/8 inches framed_Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico City

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Frida Kahlo, Me and My Parrots (Yo y mis pericos), 1941

oil on canvas_32 x 24-1/2 inches

Private Collection © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Frida Kahlo, The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Diego, Me and Señor Xólotl [El abrazo de amor del universo, la tierra (México), Diego, yo y el señor Xólotl], 1949

oil on Masonite_27-9/16 x 23-13/16 inches_The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of Modern and Contemporary Mexican Art: Courtesy The Vergel Foundation; Muros; Costco / Comercial Mexicana

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México,

Frida Kahlo, My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree) [Mis abuelos, mis padres, y yo (árbol genealógico)], 1936

oil and tempera on metal_12-1/8 x 13-5/8 inches_The Museum of Modern Art, New York_Gift of Allan Roos, M.D., and B. Mathieu Roos, 1976_digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Photographer unknown, Frida on a boat, Xochimilco, Mexico City, n.d.

Vicente Wolf Photography Collection

Frida Kahlo, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale (El suicidio de Dorothy Hale), 1939

oil on Masonite with painted frame_23-1/2 x 19-1/2 inches framed_Collection of Phoenix Art Museum_Gift of an anonymous donor

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Julien Levy, Frida Kahlo, New York, 1938

Vicente Wolf Photography Collection

© 2001 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Frida Kahlo, Without Hope (Sin esperanza), 1945

oil on canvas mounted on Masonite_11-1/16 x 14-3/16 inches_Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico City

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

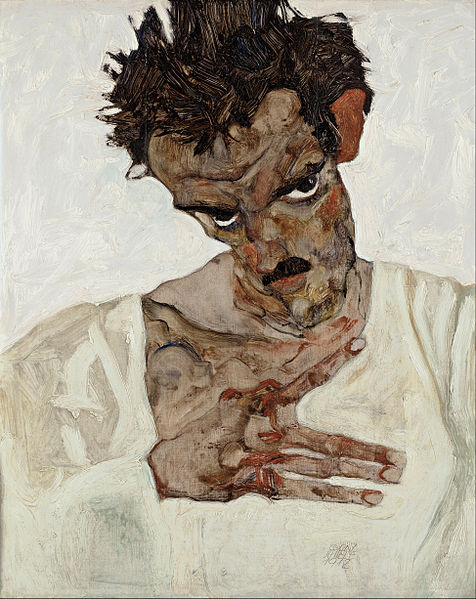

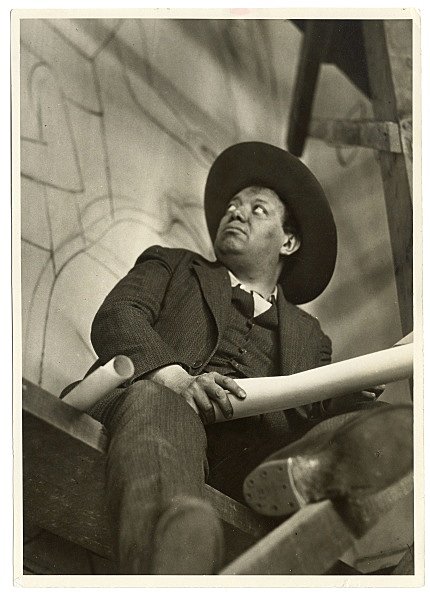

Peter A. Juley, Diego Rivera at work on Liberation of the Peon, New York, 1931

Vicente Wolf Photography Collection

© Peter A. July Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Frida Kahlo, Still Life: Pitahayas (Naturaleza muerta: Pitahayas), 1938

oil on aluminum_10 x 14 inches_Collection of Madison Museum of Contemporary Art_Bequest of Rudolph and Louise Langer

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Necklace (Autorretrato con collar), 1933

oil on metal_13-3/4 x 11-7/16 in. (35 x 29 cm)_The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of Modern and Contemporary Mexican_Art: Courtesy The Vergel Foundation; Muros; Costco / Comercial Mexicana

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Photographer unknown, Frida Kahlo in her studio at Casa Azul, Coyoacán, n.d.

Vicente Wolf Photography Collection

Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Frida Kahlo, Coyoacan, circa 1938

Vicente Wolf Photography Collection

Courtesy of Manuel Alvarez Bravo Estate and ROSEGALLERY

Frida Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931

oil on canvas_39-3/8 x 31 inches

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Albert M. Bender Collection, Gift of Albert M. Bender © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Frida Kahlo, My Nurse and I (Mi nana y yo), 1937

oil on metal_12 x 13-3/4 inches_Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico City

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Guillermo Kahlo, Kahlo family portrait, Coyoacán, Mexico City, 1926

Vicente Wolf Photography Collection

© Courtesy of Guillermo Kahlo Estate

Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait, 1930

oil on canvas_26 x 22 inches

Private Collection © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

Frida Kahlo, Moses (Moisés), 1945

oil on Masonite_20 x 37 inches_Private collection, Texas

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

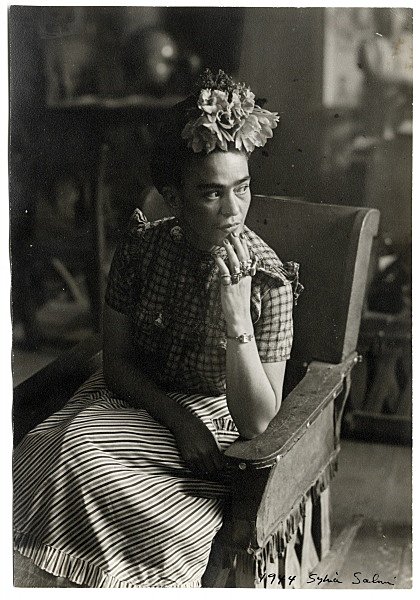

Sylvia Salmi, Frida Kahlo, 1944

Vicente Wolf Photography Collection

Frida Kahlo, Itzcuintli Dog with Me (Escuincle y yo), circa 1938

oil on canvas_28 x 20-1/2 inches_Private Collection

© 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av., Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

.jpg!Large.jpg)

_(1).jpg)

+Through+the+Vines+1908.jpg)

.jpg!Large.jpg)

_-_WGA10422.jpg/507px-El_Greco_-_A_Boy_Blowing_on_an_Ember_to_Light_a_Candle_(Sopl%C3%B3n)_-_WGA10422.jpg)

.jpg!HalfHD.jpg)

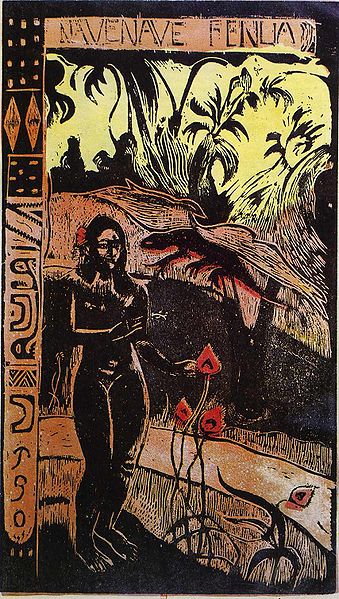

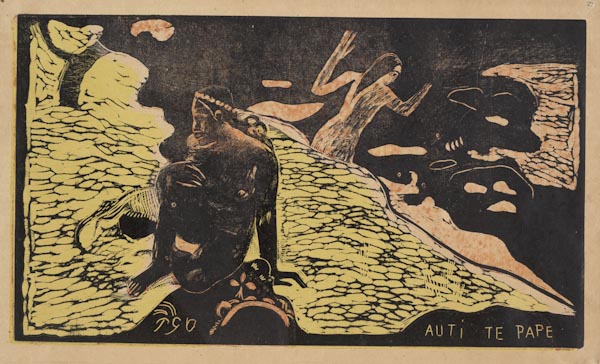

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/463px-Paul_Gauguin_-_Ia_Orana_Maria_(Hail_Mary)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/378px-Paul_Gauguin_-_Noa_Noa_(Fragrant,_Fragrant)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

_-_St._Malo_(Unknown).JPG/800px-Maurice_Prendergast_(1858-1924)_-_St._Malo_(Unknown).JPG)

_-_Evening_on_a_Pleasure_Boat_(1895-1898).jpg/640px-Maurice_Prendergast_(1858-1924)_-_Evening_on_a_Pleasure_Boat_(1895-1898).jpg)

_(Spanish_-_Bullfight,_Suerte_de_Varas_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/585px-Francisco_Jos%C3%A9_de_Goya_y_Lucientes_(Francisco_de_Goya)_(Spanish_-_Bullfight,_Suerte_de_Varas_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg!Large.jpg)

,_John_Singer_Sargent,_1884_(unfree_frame_crop).jpg/300px-Madame_X_(Madame_Pierre_Gautreau),_John_Singer_Sargent,_1884_(unfree_frame_crop).jpg)