Some 50 Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings and drawings that had never before been lent from the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, were the centerpiece of an exhibition devoted to the extraordinary art collection formed by Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet (1828-1909), the physician who cared for Vincent van Gogh in the months prior to his suicide in 1890, and who was immortalized in several renowned portraits by the artist.

The exhibition, which featured more than 130 works in all, includes an additional 40 paintings and works on paper from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and other collections in Europe and America that also once belonged to the legendary Dr. Gachet, who was both friend and patron to the artists — Monet, Pissarro, Guillaumin, Renoir, Sisley, and above all, Cézanne and Van Gogh — whose works he collected.

On view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art May 25 through August 15, 1999,

Cézanne to Van Gogh: The Collection of Doctor Gachet offered a unique overview of this fascinating assemblage, including major examples of these artists' work, copies made after them by Gachet and other amateur artists in his circle, and an interesting array of souvenirs, such as artists' palettes, tubes of paint, and various props, that record Gachet's close relationship with these 19th-century masters.

The exhibition also offered a detailed look not only at Dr. Gachet, but also his son and heir, Paul Gachet fils (1873-1962), who, following his father's death, kept the collection virtually hidden from sight in the family house in Auvers for more than half a century — frustrating art historians and, given the Gachets' practice of copying, raising questions about the authenticity of several key works — before donating a major portion of the collection to the French state over a period of years beginning in 1949.

The exhibition was organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Réunion des musées nationaux/Musée d'Orsay, Paris, and the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

About Doctor Gachet

Paul-Ferdinand Gachet maintained a medical practice in Paris, however, he spent most of his time at his country house in Auvers-sur-Oise, some 20 miles from the capital, where he became acquainted with a number of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters who worked in the area, including C#&233;zanne, Pissarro, and Guillaumin. The house was filled with works of art, most of which were tokens of friendship and souvenirs of artistic interchange, as well as assorted antiques, a printing press, and an infamous menagerie of animals. Here, Céézanne made a series of still-lifes based on vases and other objects in the Gachet household; Pissarro, working nearby in Pontoise, painted landscape motifs drawn from the environs; and several artists — among them Amand Gautier, Norbert Goeneutte, and Van Gogh — painted portraits of Dr. Gachet.

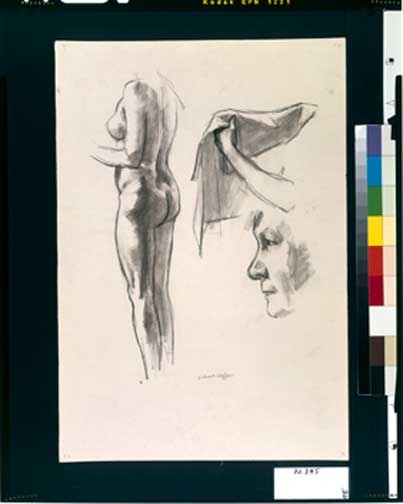

Though he was a physician by profession, Gachet — a fascinating, multifaceted, and eccentric individual — was also an artist in his own right under the pseudonym Paul van Ryssel ("Paul of Lille"), a name he adopted from the Flemish name for his hometown. His son Paul Gachet fils became an artist as well, adapting the name Louis van Ryssel. The artistic efforts of father and son extended from Dr. Gachet's avant-garde etchings and prints to the canvases they painted in an Impressionist idiom, and the copies both made after pictures that they owned by Cézanne, Pissarro, Van Gogh, and others.

Exhibition Highlights

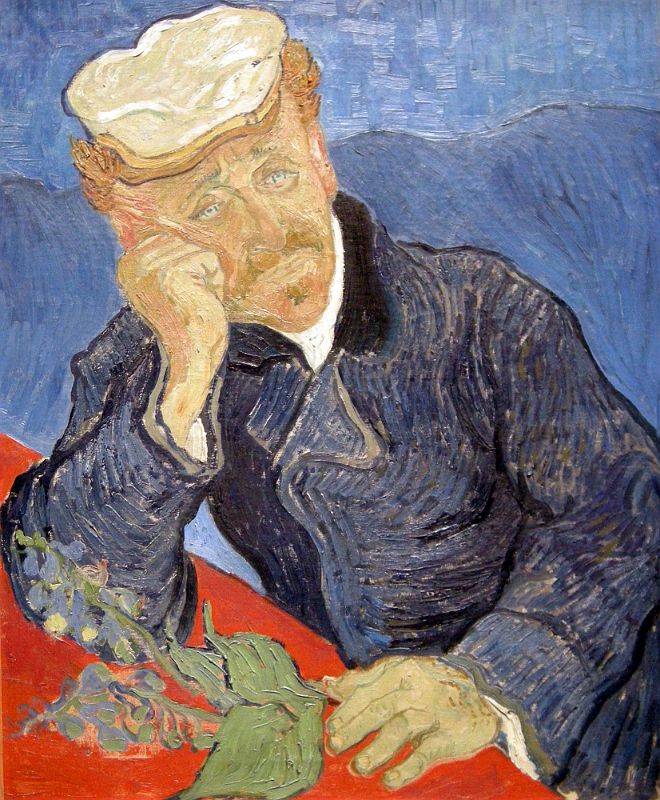

Cézanne to Van Gogh marked the first time since a 1954-55 Paris exhibition commemorating the gift by Paul Gachet fils that an exhibition focused on the collection and the first time ever that the Gachets' artistic endeavors have been presented alongside the work of the masters they copied. The exhibition featured nearly 60 paintings, including approximately ten works each by Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Guillaumin, with a representative selection of paintings by Pissarro, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, and the Gachets themselves. Adding further context to this presentation, the various artists' "souvenirs" — vases that appear in Cézanne's still lifes and Van Gogh's flower paintings, the white visor cap that Dr. Gachet wears in Van Gogh's celebrated oil portrait and the copper plate used for the artist's etched portrait of Dr. Gachet, as well as other related objects — were displayed adjacent to the works of art.

Highlights of the paintings in the exhibition included

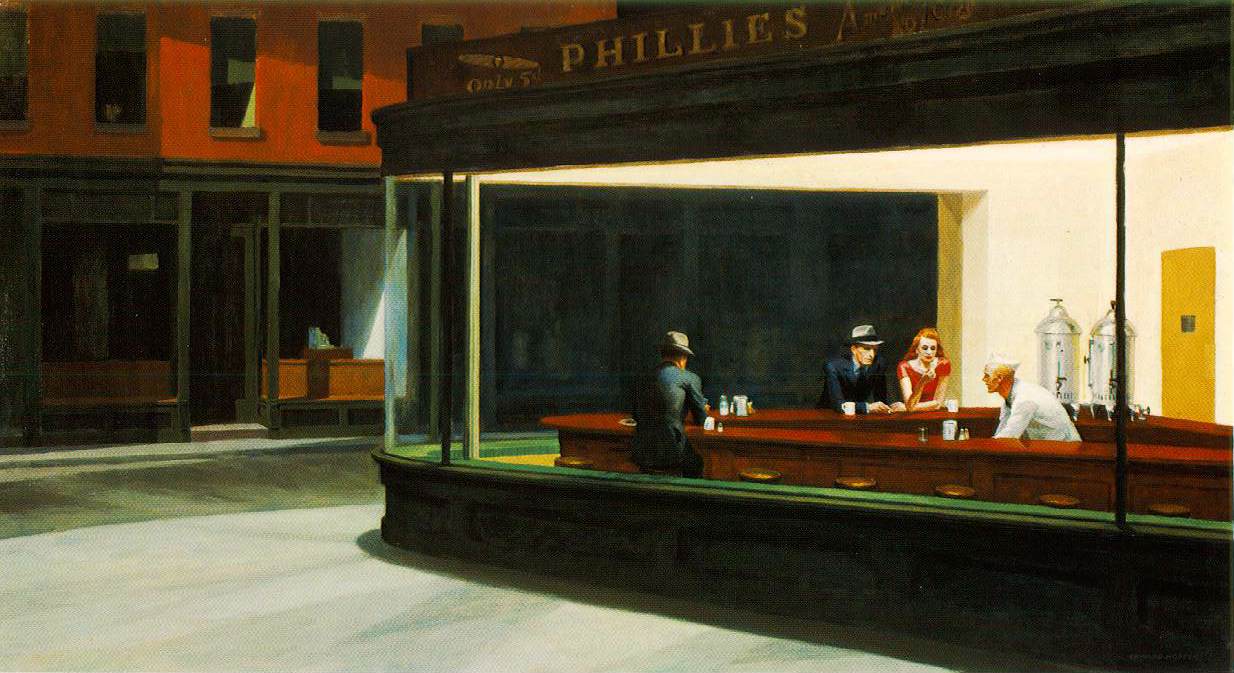

![]()

Cézanne's

A Modern Olympia (1873-74)

![]()

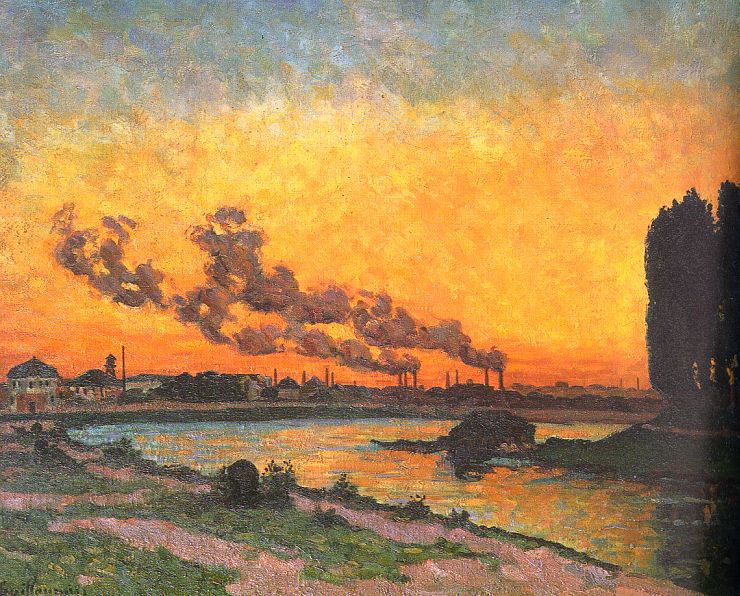

and Guillaumin's

Sunset at Ivry (ca. 1872-73),

which Dr. Gachet lent to the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874.

Other paintings by Cézanne included

![]() Green Apples (ca. 1872-73),

Green Apples (ca. 1872-73),

![]()

Dr. Gachet's House at Auvers (1872-73),

![]()

and Bouquet in a Small Delft Vase (1873). The Delft vase depicted was among the souvenirs on view.

Pissarro was represented by several exceptional canvases, including

![]() Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes

Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes (c. 1871-72),

which Van Gogh admired and described in a letter to his brother Theo,

![]()

and

Road at Louveciennes (1872).

![]()

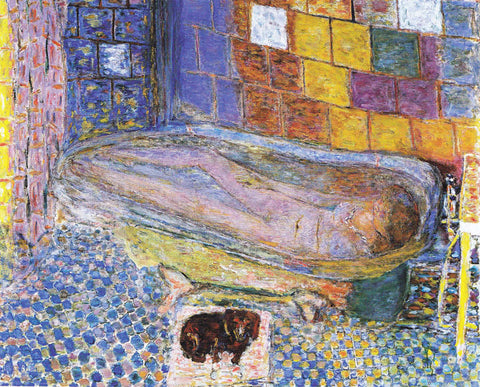

Guillaumin's

Reclining Nude (ca. 1872-77)

also caught the attention of Van Gogh when he visited Dr. Gachet's house.

![]()

Van Gogh's own works on view included the famous

Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890),

![]()

as well as his haunting

Self-Portrait (1889),

one of the last made before his suicide.

Of his landscapes in the exhibition, the intimate view of

![]() Dr. Gachet's Garden

Dr. Gachet's Garden (1890),

with its profusion of riotous flora,

contrasts markedly with the expansive vista of

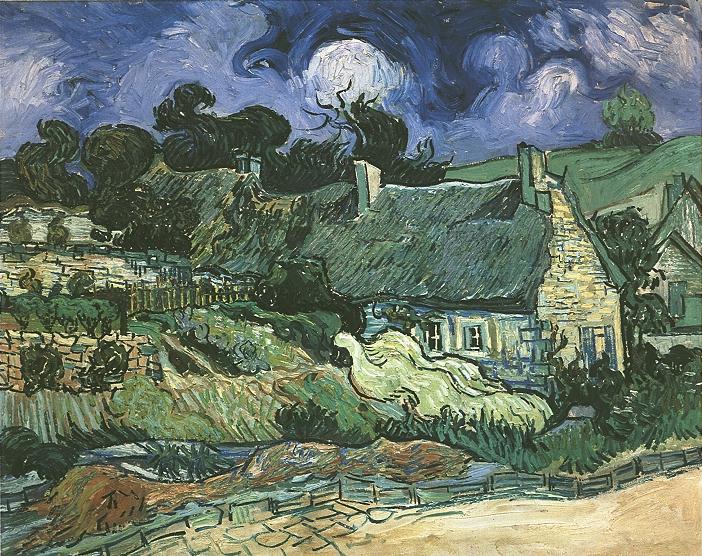

![]() Thatched Huts at Cordeville, Auvers

Thatched Huts at Cordeville, Auvers (1890),

yet both reveal Van Gogh's characteristically exuberant brushwork and brilliant palette.

Among the paintings by Dr. Gachet are the still-life Apples, a copy after Cézanne's A Modern Olympia, and a copy after Pissarro's Study at Louveciennes, Snow, a work that Gachet never owned, but had borrowed from Pissarro for the purpose of copying. An indication of the degree to which Dr. Gachet's house was a vortex of artistic interchange is revealed not only in the copies that amateurs such as the Gachets made of the artists' paintings, but in the copies that the artists themselves made of each other's works.

The exhibition included Cézanne's etching,

Sailboats on the Seine at Bercy (after Guillaumin) as well as his still-life painting (here is a similar painting):

![]() The Seine At Bercy Paintings After Armand Guillaumin

The Seine At Bercy Paintings After Armand Guillaumin by Paul Cézanne

![]() Bouquet with Yellow Dahlia

Bouquet with Yellow Dahlia (1873), which incorporates the same tablecloth and similar motifs found in a Guillaumin still-life that was also painted in Gachet's house at around the same time.

![]()

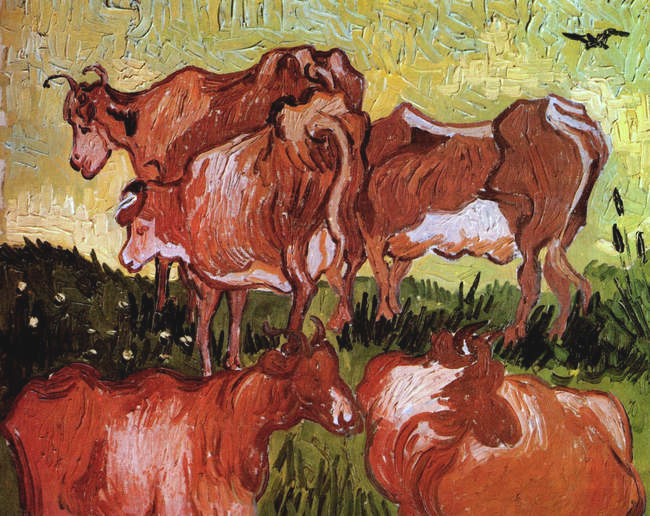

Van Gogh's painting

Cows (after Van Ryssel and Jordaens)is an oil copy of a Gachet etching of a Jordaens oil. Continuing this tradition, Paul Gachet fils, painting as Louis van Ryssel, was also inspired by the works in his father's collection, making oil and watercolor copies of many paintings. In other works, he adopted the style and palette of Van Gogh to paint works of his own conception, including a portrait of Van Gogh's mother, which the younger Gachet presented to Vincent's nephew (also named Vincent van Gogh) in 1905.

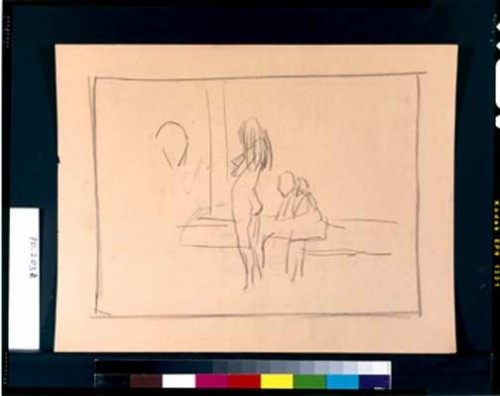

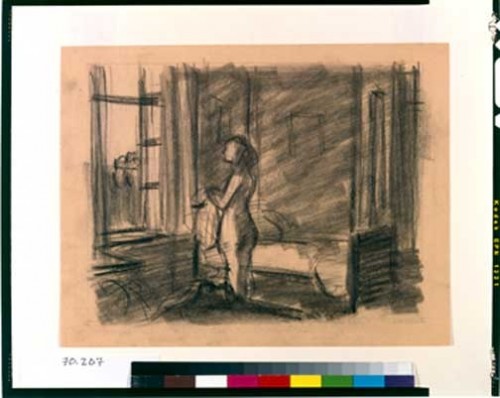

Among the more than 50 works on paper were drawings by the masters and the Gachets and other amateurs, about 25 watercolor copies of paintings, and a selection of prints made in Dr. Gachet's attic studio by Cézanne, Pissarro, Van Gogh, and the Gachets. The only etchings ever created by Cézanne

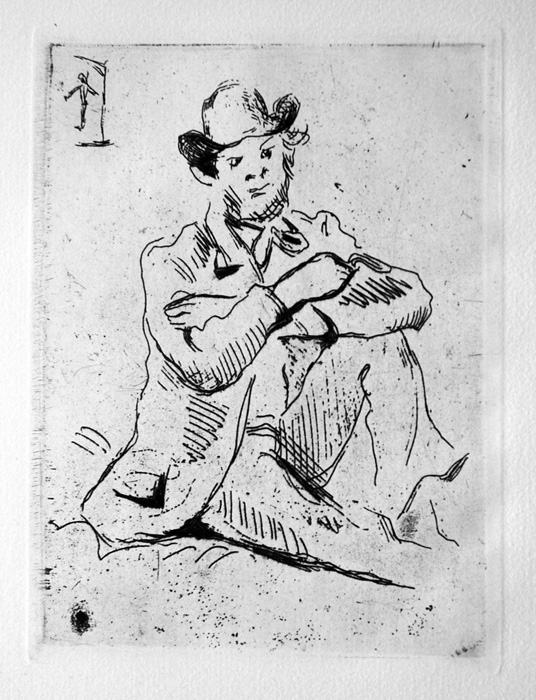

![]() Guillaumin au pendu (Salomon 2 ii/ii). Original etching, 1873. Edition unknown (c. 1000 unsigned impressions).

Guillaumin au pendu (Salomon 2 ii/ii). Original etching, 1873. Edition unknown (c. 1000 unsigned impressions). The poet and painter Armand Guillaumin was Cezanne's friend and probably introduced him to etching. Here we see him siitting beneath the sign of the inn, Le Pendu / The Hanged Man

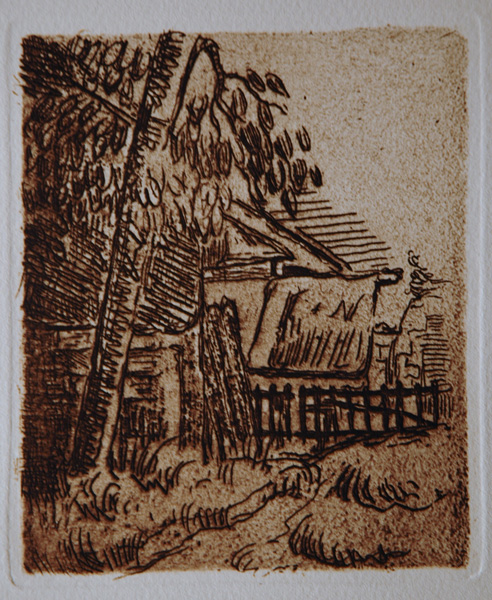

![]() Paysage à Anvers (Salomon 5). Original etching printed in color, 1873. Edition: 600 impressions pulled in1914 for Homage to Cezanne.

Paysage à Anvers (Salomon 5). Original etching printed in color, 1873. Edition: 600 impressions pulled in1914 for Homage to Cezanne.and Van Gogh were made in Dr. Gachet's house, and the exhibition included impressions of all five prints by Cézanne and the sole etching of Van Gogh's career —

![]() Portrait of Dr. Gachet (The Man with a Pipe)

Portrait of Dr. Gachet (The Man with a Pipe)— shown in four differently colored prints in addition to the original copper plate. Another rarely exhibited treasure, Van Gogh's sketchbook from his Auvers period, was also featured in the exhibition.

The watercolors on view included a selection of works copied from Van Gogh's oil paintings in the Gachet collection that were made by Blanche Derousse (1873-1911), a local seamstress, amateur artist, and friend of the Gachet family in Auvers. Originally intended to illustrate a never-realized catalogue of Dr. Gachet's collection of Van Gogh canvases, these intimately scaled works offered an enlightening overview of the scope and quality of the works once owned by Dr. Gachet, before they were dispersed through sales and donations made by his son.

Perhaps the most poignant example in the exhibition of the bond between Dr. Gachet and Van Gogh was Gachet's charcoal portrait of the artist on his deathbed. Further testament of the high esteem in which artist and doctor held one another is a letter from Vincent to his brother Theo, describing Dr. Gachet and his new surroundings in Auvers. Two letters sent by Dr. Gachet to Theo include the urgent note that Vincent had shot himself and imploring Theo to come to Auvers. The second letter, written after Vincent's death, in which Dr. Gachet characterizes the artist as a "giant" and a "philosopher" and writes of his profound appreciation for Van Gogh's paintings, had only recently been rediscovered after being lost for decades. Several photographs of the Gachet household, detailing how the collection was displayed during their lifetimes, were also on view.

During those decades in which the works were sequestered in the Gachet house — most had never been photographed or exhibited prior to their donation — speculation swirled around the collection, the Gachets' intentions for its disposition, and the veracity of the younger Paul Gachet's accounts of the family's interaction with these now-celebrated artists. The exhibition provided a unique opportunity to compare great paintings by Cézanne and Van Gogh with copies made by the Gachets and others in their circle and to reassess, in light of new technical and documentary findings, those works — such as the Orsay version of Portrait of Dr. Gachet — that have been the subject of particular controversy. Most of the copies had never before been exhibited and visitors to the exhibition could evaluate for themselves whether either Gachet had the impetus or, more importantly, the artistic ability to convincingly fake the work of the masters.

Organizers

The exhibition was co-organized by Susan Alyson Stein, Associate Curator of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Anne Distel, Chief Curator, Musée d'Orsay. Andreas Blühm, Head of Exhibitions, and Sjraar van Heugten, Curator of Drawings and Prints, both of the Van Gogh Museum, are responsible for coordinating the exhibition in Amsterdam.

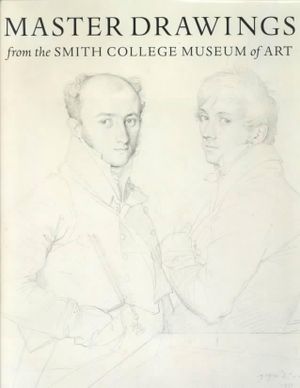

Catalogue

![]()

The

fully illustrated catalogue that accompanied the exhibition addresses these issues and others in historical and technical essays and entries that include a wealth of information that has newly come to light. The catalogue, published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, also documents the contents and history of the entire Gachet collection — beyond what was donated to the French state — in essays, as well as a checklist of artists and works in the collection, a summary catalogue of approximately 150 works, and an illustrated checklist of copies. Featuring 500 illustrations, including 117 in color, the 328-page catalogue is available in both hardcover and paperback.

Travel Information

Cézanne to Van Gogh: The Collection of Doctor Gachet premiered at the Grand Palais, Paris (January 30 through April 26, 1999), and, following the Metropolitan's presentation, was on view at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam (September 24 through December 5, 1999).

_-_WGA03122.jpg/461px-Jan_de_Bray_-_The_de_Bray_Family_(The_Banquet_of_Antony_and_Cleopatra)_-_WGA03122.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/593px-Egon_Schiele_-_Self-Seer_II_(Death_and_Man)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

-large.jpg)

.+The+Provencal+Jug+1930.jpg)