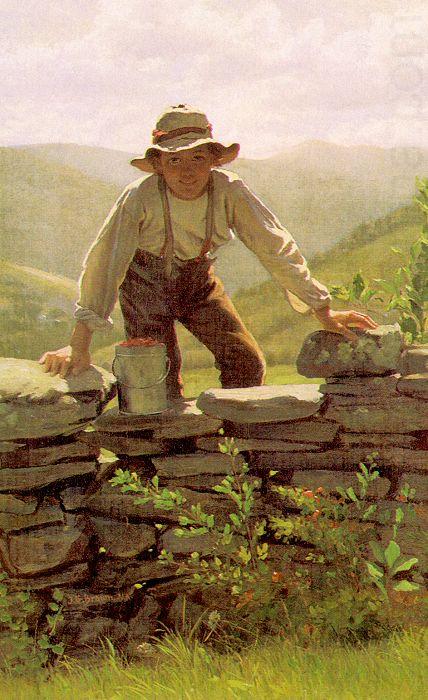

A rare opportunity to trace the development of American art across more than 200 years was offered in American Spectrum: Paintings and Sculpture from the Smith College Museum of Art, on view March 4-May 27, 2001 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The collection of 62 works dating from 1733 to 1948 traveled to eight venues in the United States while the Smith College Museum of Art in Northampton, Massachusetts was closed for renovation and expansion. America's leading masters were represented in this show, including the painters Thomas Cole, John Singleton Copley, John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, and Childe Hassam, and the sculptors Alexander Calder, Daniel Chester French, Elie Nadelman, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

From

+Mrs.+John+Erving+(Abigail+Phillips,+1702-1759).jpg)

John Smibert's Mrs. John Erving (c. 1733)

to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith's The Red Mean: Self-Portrait (1992),

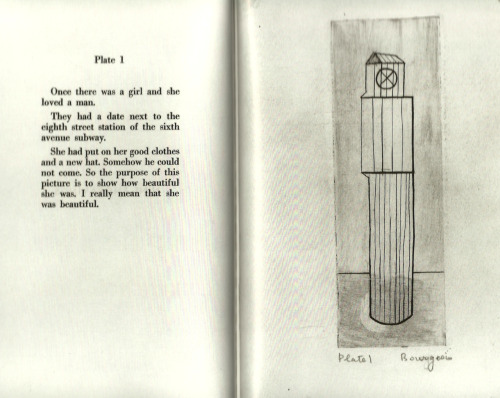

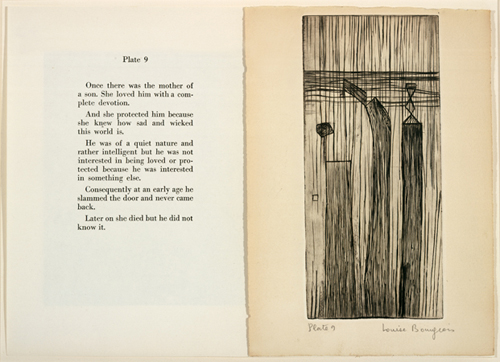

"American Spectrum: Paintings and Sculpture from the Smith College Museum" spanned over 250 years of American art. The seventy-five works selected for the exhibition represented many of America's most revered artists including painters Joseph Albers; Thomas Cole, NA; Winslow Homer, NA; Edward Hopper; George Inness, NA; Franz Kline; Robert Motherwell; Georgia O'Keeffe; John Singer Sargent, NA, and Gilbert Charles Stuart. Sculptors include Alexander Caider; Daniel Chester French, NA; Elie Nadelman; Louise Nevelson; and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, NA, among others.

The Smith collection began to take shape in 1879 when the college's first president L. Clarke Seelye decided he wanted students to have an art gallery where they could "be made directly familiar with the famous masterpieces." His early strategy was to acquire reproductive prints and casts of historic pieces, and to buy original contemporary art. Works in this exhibition that he bought directly from the artists include

/In_Grandmothers_Time.jpg)

Thomas Eakins's In Grandmother's Time

and Albert Pinkham Ryder's Perrette,

and possibly William Merritt Chase's Woman in Black.

Among them was Rockwell Kent's early work

Dublin Pond (1903),

a painting which the artist had recently submitted for the National Academy's Annual, purchased by the museum when the artist was only twenty-one, and the first works by the artist to be part of an institutional collection.

After Seelye firmly established the museum's American holdings, the collection continued to evolve into the 20th-century through equally astute acquisitions. Purchased in 1931,

Edith Mahon (1904)

was widely considered one of Thomas Eakins' finest portraits, and also constituted the first work by Eakins in any public art collection.

Notable bequests were also crucial in building the collection. They include

John Singleton Copley 's portrait of the Boston merchant, The Honorable John Erving, (c. 1772),

presented to the college by the judge's descendant and Smith Alumnus Alice Erving.

Gifts of modern and contemporary art include superb works by Arthur G. Dove, William Glackens, NA, Childe Hassam, NA, Willem de Kooning, Louise Nevelson, Joan Snyder, and Donald Sultan, and many others.

Albert Bierstadt, Echo Lake, Franconia Mountains, New Hampshire, 1861, oil on canvas, Smith College Museum of Art, Purchased with the assistance of funds given by Mrs. John Stewart Dalrymple (Bernice Barber, class of 1910), 1960.37)

Stories behind some of the works make them all the more intriguing.

Edward Hopper's Pretty Penny (1939) is a joyous, light-filled portrait of the house of the actress Helen Hayes.

Hopper was commissioned to do the painting, but was reluctant to accept at first because he considered it tradesman's work. He eventually relented, creating a work without the darkness and alienation so common in his paintings of American houses. Hayes, who received an honorary doctorate from Smith in 1940, gave the painting to the museum in 1964.

Edwin Romanzo Elmer, a painter who died unknown, is represented by two paintings in the exhibition,

Mourning Picture (1890)

and A Lady of Baptist Corner, Ashfield, Massachusetts (the Artist's Wife), (1892).

Mourning Picture is a family portrait of the artist, his wife, and their daughter, who had died not long before, and a pet sheep against the backdrop of a Victorian house. It was first shown in a post office in 1890 and then was not seen again until 1950 when the artist's niece showed it to Henry-Russell Hitchcock, then director of the Smith Museum. Hitchcock recognized its value at once. It became one of the most popular and most frequently reproduced paintings in the collection. In the portrait of his wife operating a machine he invented to make whip snaps (the braided end of horsewhips), Elmer shows his love of detail - from the design of the carpet to the play of light and shadow in the scene.

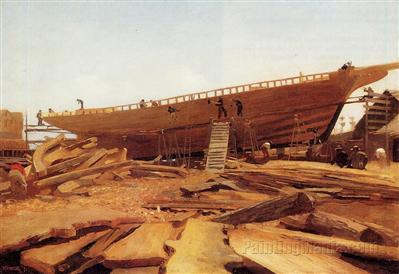

Other paintings in the exhibition gloriously document man's achievements in transportation and industry.

Winslow Homer's Shipyard at Gloucester (1871) captures a crew building a schooner so accurately that a historian has been able to determine the hull type and the details of the ship under construction.

Among the dozen sculptures in the exhibition were Elie Nadelman's elegantly designed Resting Stag (c. 1915) and Augustus Saint-Gaudens's Diana of the Tower (1899). Nadelman's deer, in gold-leafed veneer and a wood-veneered base, was created at the height of his career. Saint-Gaudens's bronze sculpture is one of a number of reductions the artist made of Diana, an 18-foot figure that sat atop a 330-foot-high tower at Madison Square Garden in New York at the turn of the century. The sculpture was created as weathervane. The Smith Museum's variant is 36 inches high and the only known kinetic version.

A 307-page catalogue, Masterworks of American Painting and Sculpture from the Smith College Museum of Art, accompanied the exhibition. In the book, 79 of the museum's most important American works are illustrated in full color and discussed in comprehensive essays. An illustrated checklist with 85 additional works from the museum is included. Linda Muehling, associate curator of painting and sculpture at Smith Museum, is the editor and principal author.

Childe Hassam, White Island Light, Isles of Shoals, at Sundown, 1899, oil on canvas, Smith College Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold D. Hodgkinson (Laura White Cabot, class of 1922), 1965.4

American Spectrum: Paintings and Sculpture from the Smith College Museum of Art was organized by the Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts.

The eight venues for this exhibition were: Faulconer Gallery at Grinnell College in Grinnell, Iowa, February 5-April 23, 2000; National Academy of Design Museum, New York, June 21-September 10, 2000; Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida, October 28, 2000-January 7, 2001; the MFAH, March 4-May 28, 2001; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, June 29-September 30, 2001; Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, October 28, 2001-January 13, 2002; Tucson Museum of Art, Tucson, Arizona, February 16-April 28, 2002; and Katonah Museum of Art, Katonah, New York, June 23-September 15, 2002.

.jpg/487px-Nicolas-Pierre-Baptiste_Anselme,_called_Baptiste_a%C3%AEn%C3%A9_by_Jean-Baptiste_Greuze_(1725_-_1805).jpg)

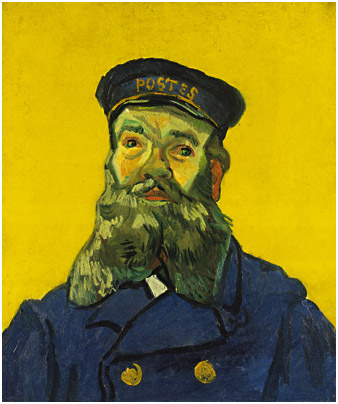

_van_Gogh_Getty.jpg/452px-Portrait_of_the_Postman_Joseph_Roulin_(1888)_van_Gogh_Getty.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/415px-Hans_the_Younger_Holbein_-_A_Lady_with_a_Squirrel_and_a_Starling_(Anne_Lovell%3f)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)