ARTISTS

Coe, Sue

Kollwitz, KätheESSAY

All good art is political! There is none that isn’t. And the ones that try hard not to be political are political by saying, “We love the status quo.”... I’m not interested in art that is not in the world.—Toni Morrison

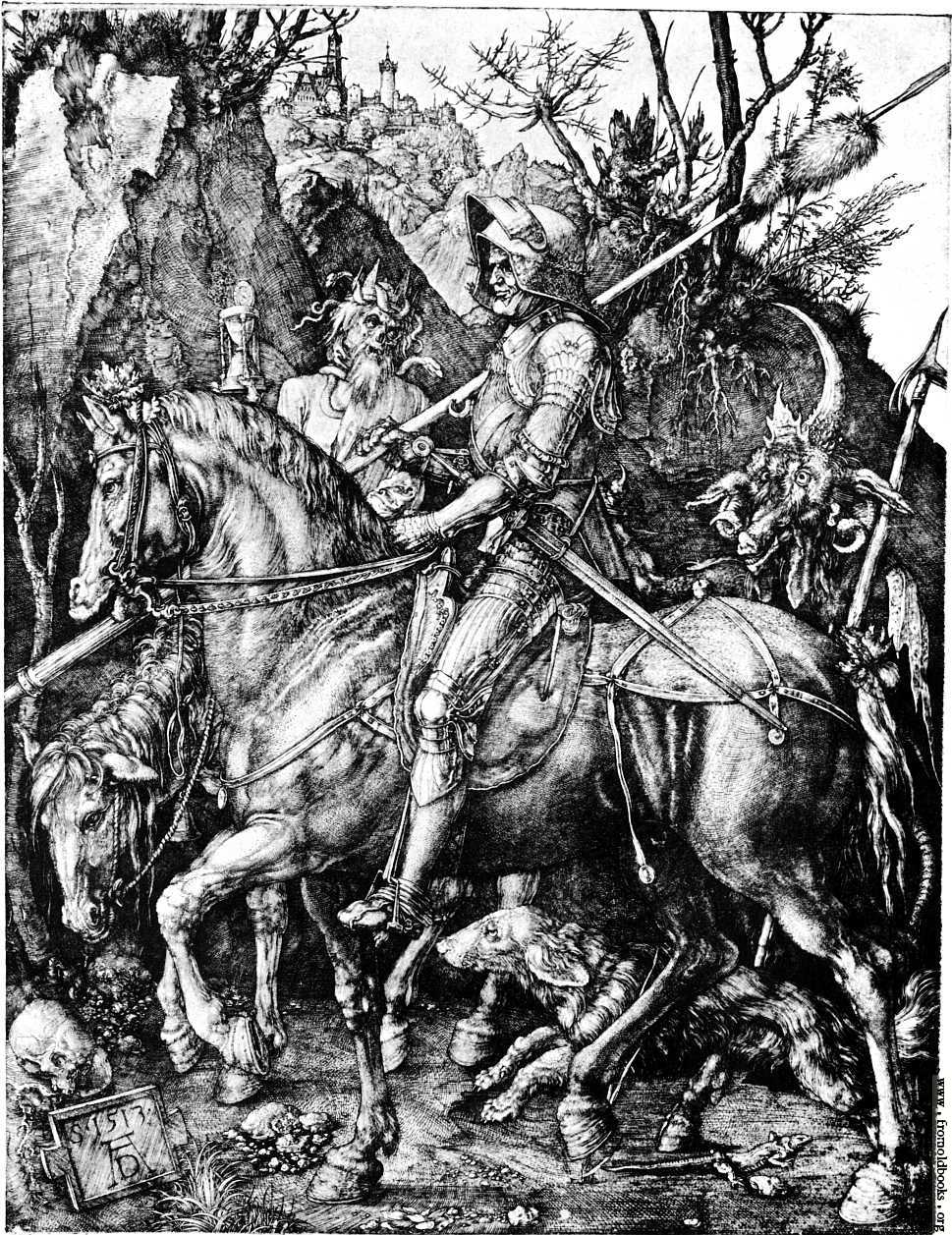

Prior to the twentieth century, art’s political grounding was taken for granted. Most European art—religious scenes, portraits and history painting—affirmed the values and legitimacy of the ruling class. As hereditary monarchs came under fire, first in the French Revolution and then in the more widespread but short-lived revolts of 1848, artists gradually lost their aristocratic support base. Painters like David, Ingres and Delacroix embraced the new order, helping shape the myth of modern France as a land of liberty, fraternity and equality. Others assumed a more critical stance. Daumier, whose caricatures at one point landed him in prison, lobbied for greater social justice. Goya, though employed by the Spanish court, created the satirical etching cycle

Caprichos and, in response to Napoléon’s aggressive imperialism, the scathing

Disasters of War. Egalitarian idealism, coupled with growing social unrest, prompted artists more frequently to depict peasants and workers. Art remained rooted in political realities, but the emphasis shifted.

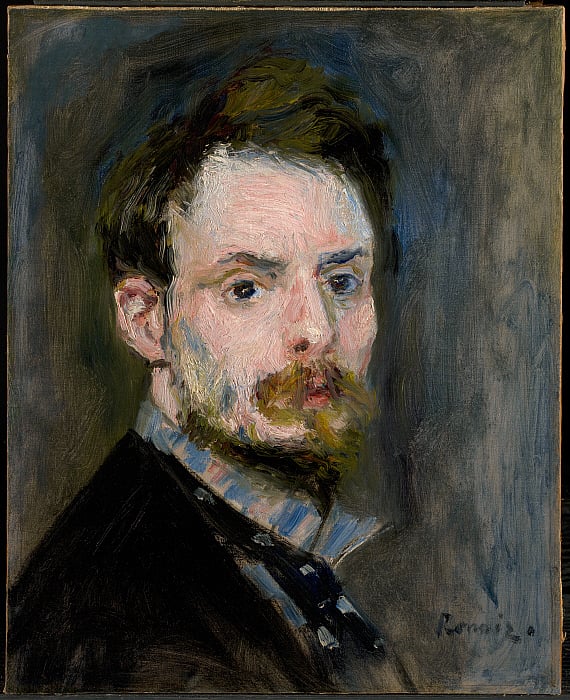

A significant number of artists identified with the forces of reform. The descriptor “avant-garde,” first applied to artists in 1825 by the socialist thinker Olinde Rodrigues, originally had political connotations. Artists, Rodrigues thought, were natural leaders in the struggle to remake society. The modernist stylistic upheavals that swept through Europe at the turn of the last century were not about “art for art’s sake.” Artists were looking for new forms that would give expression to the radically new circumstances of modern life. They wanted to sweep away the stale pictorial and moral conventions of the entrenched bourgeoisie. That modernism could indeed be perceived as a political threat was later affirmed by its suppression under Hitler and Stalin.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) grew up in a family of committed Christian dissidents. Her maternal grandfather, Julius Rupp, was the pastor of an underground Protestant congregation, the Free Society of Königsberg. Hounded by the police, fined and jailed, Rupp taught the future artist to value freedom of conscience over obeisance to the state. Though Kollwitz was not especially religious, she believed in duty, sacrifice and service to a higher cause. She viewed socialism as a secular path to “God’s kingdom on earth”—imagined by her grandfather as a classless society with equality and justice for all. Karl and Konrad Schmidt, the artist’s father and brother, were among the founding members of the German Social Democratic Party.

The German socialists supported women’s rights, and therefore Karl Schmidt encouraged his daughter’s professional aspirations. He dreamed she might become an acclaimed history painter. But such an achievement—then the pinnacle of artistic success—was unattainable for a woman. Prohibited from enrolling at the Academy, females were shunted into the lesser areas of creative endeavor—crafts, printmaking, at most landscape or portrait painting. Fearful of competition, men not only restricted women’s career options, but issued lengthy prescriptive pronouncements about the nature of femininity. Women, they opined, lacked the intellect, objectivity and spiritual understanding required to create anything of note; females could best serve the arts as muses. It was perhaps with these ideas in mind that Kollwitz later ascribed her professional persistence to the “masculine” aspects of her character.

Propelled by personal preference as well as the available educational opportunities, Kollwitz made her way, through a succession of women’s art schools and private lessons, to printmaking. It was a fortuitous choice, because history painting in the grand tradition was waning, along with the aristocracy. History as a subject, however, could better be depicted in a sequence of prints than in a single painted image. Inspired by the print cycles of Max Klinger, Kollwitz’s first foray in this realm was

Revolt of the Weavers, a series of three lithographs and three etchings loosely based on Gerhart Hauptmann’s play about the 1844 Silesian weavers’ rebellion. The

Weavers prints (1893-97) evidenced a mastery of craft and nuance heretofore seen only in academic history painting: the orchestration of complex figural groupings and subtle chiaroscuro effects in a variety of evocative pictorial spaces to convey a compelling dramatic narrative. Kollwitz’s intensive engagement with the expressive capabilities of printmaking techniques parallels, and to some extent precedes, the work of modernists such as Edvard Munch and the German

Brücke artists, but Kollwitz’s prints were revolutionary less in form than in content. And while for male modernists printmaking was always secondary to work in other, more “important” mediums, for Kollwitz it remained primary.

Revolt of the Weavers and Kollwitz’s next, similarly themed print cycle,

Peasant War (1902-08), treated both genders as comrades in arms. This was in keeping with the tenets of German socialist feminism, which held that proletarian men and women were united under the yoke of capitalism and would be liberated together when that yoke was lifted. However, through exposure to the working-class patients of her husband Karl Kollwitz, a physician, the artist began to recognize that proletarian women had unique problems stemming from their subordination to and dependency on proletarian men. “As soon as the man drinks or gets sick or loses his job, the same thing always happens,” Kollwitz observed. “Either he hangs like a dead weight on his family and lets them support him...or he becomes depressed... or crazy... or he kills himself.”

Kollwitz grew increasingly concerned with women’s issues such as inadequate wages, temperance, domestic violence and lack of access to contraception or abortion. After completing the

Peasant War series, she took her subjects from lived experience rather than history, and motherhood came to assume a central role in her work. The mother’s instinctual drive to save her children from harm was rendered with an evocative realism that encouraged viewers to empathize with the woman’s plight. At the same time, the images were a symbolic call to action, an invocation to fashion a world that would be safe for future generations.

Like many progressive Europeans on both sides of the conflict, Kollwitz initially imagined that World War I would wipe away the stale remnants of bourgeois materialism and lead to a renewal of human society. Steeled by a deeply ingrained sense of duty, she was even prepared to sacrifice her teenaged son, Peter, for the greater good. She grudgingly granted him permission to volunteer, and was devastated when he fell on the Belgian front scarcely two months later. It was hard for the artist to accept that her boy had died for nothing. She only gradually grew to understand not just that this particular war was pointless, but that all wars hobble humanity by eviscerating the rising generation. “Seed-corn,” Kollwitz declared (quoting Goethe), “must not be ground.”

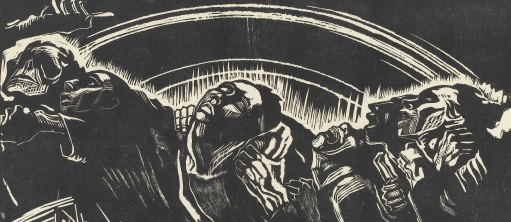

World War I transformed Kollwitz into a committed pacifist. Unlike Otto Dix and George Grosz, whose depictions of the war were conditioned by their army experiences, her

War cycle (1921-22) emphasized the home front. In the first plate,

The Sacrifice (Das Opfer), a mother holds her infant aloft, as though offering him to the gods. But the German word

Opfer also means “victim,” and it is clear that the artist’s interpretation is elegiac rather than heroic. Another plate,

The Volunteers, shows a surge of youth heedlessly following the drumbeat of death, Peter’s face recognizable at the forefront. In a 1923 antiwar poster commissioned by the International Federation of Trade Unions and distributed in fourteen languages, Kollwitz focused on the “survivors,” whom she described as “women huddled together in a black lump, protecting their children just as animals do with their own brood.” In 1924, on the tenth anniversary of World War I, she created the iconic poster

Never Again War!No longer the naïve revolutionary who once dreamed of joining her father and brother on the barricades, Kollwitz found it impossible to take sides in the political conflicts that roiled the Weimar Republic. The Social Democrats were too susceptible to rightwing pressure, the Communists too prone to violence. Nevertheless, Peter’s death had redoubled her desire to serve humankind in the broadest sense. She was quick to lend her art in support of any cause that moved her: the food shortages that swept through Germany, Austria and Russia after the war, the plight of prisoners, the poor and, as always, the extra burden shouldered by women and children. Her aim was to “bear witness,” to “express...the suffering of human beings.” “My art serves a purpose,” Kollwitz continued. “I want to exert an influence in my own time, in which human beings are so helpless and destitute.”

Kollwitz’s rejection of any fixed ideology did not keep her work from being appropriated for unintended political ends. Even the Nazis, who quickly eliminated all the artist’s professional outlets, found a use for one of her lithographs,

Bread! Though Kollwitz was never a Communist, the East Germans made her their own after World War II. In the West, which sought to whitewash the reality of Nazi collusion, she was offered up as the prototypical “good German.” The evident ease with which socially engaged art could be misappropriated for propaganda purposes prompted many artists to back away from politics in the second half of the twentieth century.

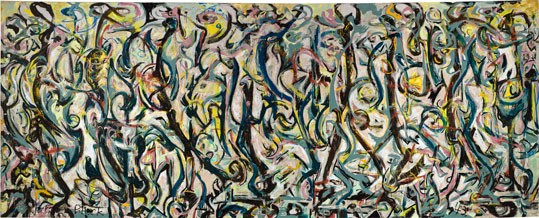

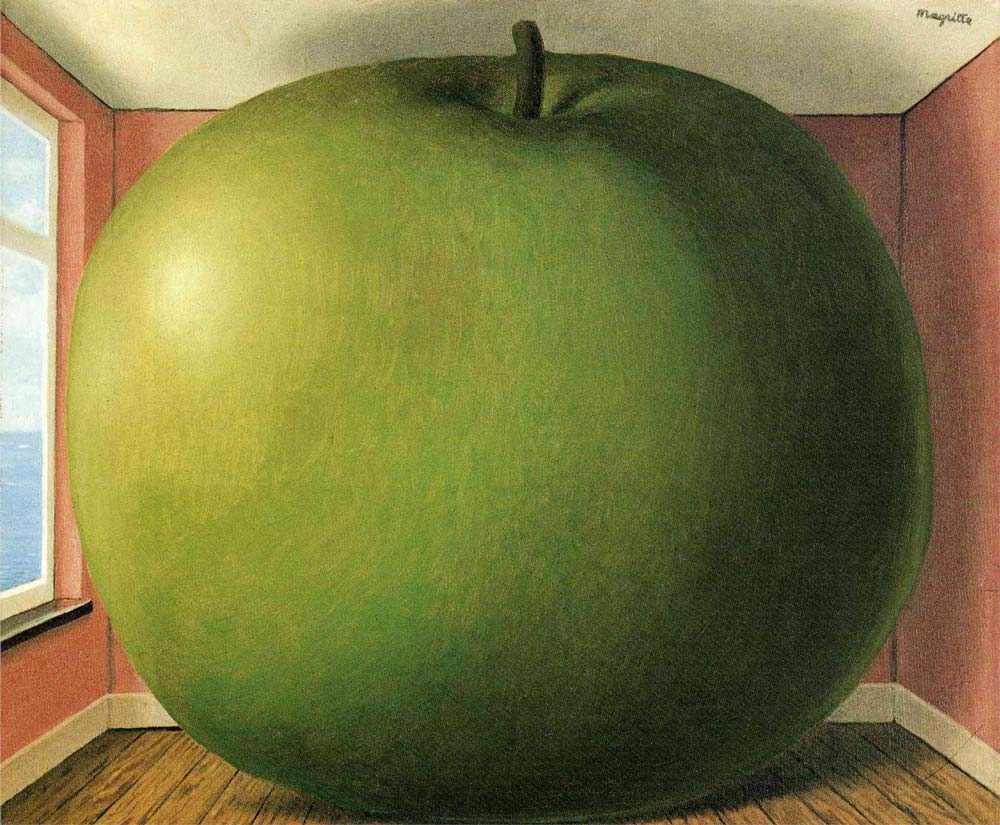

During the Cold War, U.S. cultural policy willfully discredited any sort of political art. Figurative work was dismissed based on its superficial resemblance to Soviet Socialist Realism. The history of prewar European modernism was rewritten to downplay the artists’ humanistic motivations and oftentimes socialist leanings. The critic Clement Greenberg seconded and advanced Alfred Barr’s formalist approach, which drove the agenda at the Museum of Modern Art. The goal, Greenberg decreed, was to create a work of art xso vacuous that it could not “be reduced in whole or in part to anything not itself.” Lauded for its lack of apparent content, Abstract Expressionism was used by the American government to galvanize intellectual opposition to Communism and to promote the ideal of democratic freedom abroad.

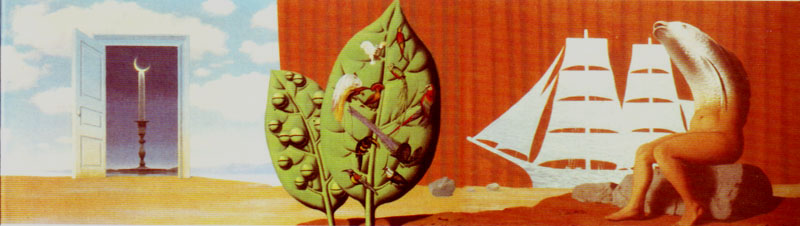

As the Cold War example demonstrates, it is remarkably difficult to disentangle even ostensibly apolitical art from the dominant power structure. The art world’s attempt to distance itself from the real world in the mistaken belief that this will keep the work “pure” does not solve the problem of misappropriation. Yet artists today remain torn between a desire to address pressing social concerns such as racism, income inequality and climate change, and the arcane visual language favored by the art world. “There’s... too much inbred art about itself or otherwise so specialized that it takes reams of explaining in almost unreadable texts just to say why it’s relevant at all,” the critic Jerry Saltz wrote in a recent jeremiad. “And the things that might feel relevant, or radical, in another context often get so buffered and wrapped in the wealth of the system...that they cease to offer anything new-seeming.” Genuine political engagement is still fundamentally at odds with contemporary art-world practice.

Sue Coe (b. 1951) is not of the art world. As a girl, she assumed she would become a factory worker, like her mother, or a secretary. Art was her escape, at first emotionally and then literally, from a working-class fate. When she was seventeen, Coe got a scholarship to attend the Chelsea School of Art in London, where she trained to be an illustrator. “I knew I had to make a living at art. No one was going to support me except myself,” she recalls. “[Illustration] was one of the few career paths that was open to women: children’s books, or greeting card illustrations, or a job making wallpaper designs (flowers are ‘female’).” In 1972 Coe moved to New York and began doing editorial illustration for

The New York Times and similar publications. Designing for the printed page taught the artist to refine her visual messaging. “If the images are not an effective lure,” she explains, “immediately compelling or accessible, the viewer will not consider reading the content.” While then unfamiliar with Klinger’s treatise

Painting and Drawing, Coe, like Kollwitz, instinctively understood that black-and-white is better suited to social criticism than color.

Coe had developed the first shreds of a political consciousness protesting the Vietnam War as a student in London. “I could see this was a moral stand,” she remembers, “even though at the time I didn’t know Karl from Groucho.” In New York, she joined the Arts Club, a place where aging Marxists, many of them survivors of the Great Depression and the McCarthy-era blacklist, met to discuss politics and print posters in support of local issues like tenants’ rights. She also broadened her aesthetic horizons, discovering the work of Daumier, Dix, Goya, Grosz and, of course, Kollwitz. Free of formalist dogma and its concomitant prescriptions, which still gripped American academia, Coe selected from the broad panoply of art history those influences that spoke to her. Tired of the constraints imposed by her editors, she also began choosing her own subjects and working on a larger scale.

Coe made her reputation as an artist in the mid 1980s with canvases based on headline events, including the notorious pool-table rape of a New Bedford woman (now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art) and the “subway vigilante,” Bernard Goetz. However (again like Kollwitz), she preferred to work in series that facilitated a more in-depth exploration. “My preference,” she says, “is to choose a topic, or have it choose me, and research it and do it well over a decade.” Coe’s approach is journalistic, and she likes to see her images accompanied by factual reportage, preferably in book form. In 1983, she published her first book, with text by Holly Metz,

How to Commit Suicide in South Africa. This and her next book,

X (The Life and Times of Malcolm X) (1986), explored the relationship between racial prejudice and genocide. More generally, Coe’s work has been an indictment of the ways in which capitalism subjugates the weak, dividing society into classes of oppressors and victims. Writing in the catalogue of her 1987-89 traveling retrospective,

Police State, the art historian Donald Kuspit credited the artist with creating “a new genre, somewhere between political cartoon and history painting.”

Essentially, Sue Coe picked up where Kollwitz left off. Coe views herself as “a witness” who uses art “to help serve justice and highlight the oppression that is concealed.” Even in our media-saturated environment, there are incidents—such as police shootings or the so-called suicides of jailed anti-apartheid activists—that can only be recreated after the fact, and locations—such as slaughterhouses—where cameras are not allowed. There are also a great many horrific places—such as prisons, AIDS wards and sweatshops—that we know exist but prefer to ignore. Coe’s job is to go there, observe and record. “People think they can choose to be indifferent,” she explains, “and the filter of art is a useful veil to present the reality. It opens up a chance to have a dialogue where the viewer asks questions and is more open to the challenge of change.”

For Coe, the predations of capitalism transcend the specifics of identity politics, uniting all socioeconomic minorities in common oppression. Growing up near a slaughterhouse on the outskirts of London, she came to view non-human animals as part of an overriding continuum of corporate violence. “We need economic, gender

and species equality,” she declares. Today the sort of widespread hunger depicted by Kollwitz is rarely seen in developed nations. Instead, we suffer from the problems of overproduction, which are subtler and more globally diffuse: malnutrition, the destruction of indigenous crops, deforestation and sweeping environmental degradation. Agribusiness and the meat industry are behind many of these calamities, Coe points out. “Animal agriculture is among the leading causes of climate change,” she says. “Animals as a class of beings are facing extinction.” Coe sees farmed animals as analogous to the children in Kollwitz’s work: innocent creatures trod under by the malevolence of an unjust system; creatures that stand both for themselves and for the future, in that their persecution reflects existential environmental concerns.

From the outset, Coe’s art has been predicated on the belief that, “if people know the facts, they’ll change the system.”

How to Commit Suicide in South Africa was widely used as an organizing tool on college campuses, supporting the disinvestment movement that ultimately contributed to the end of apartheid. Since Coe began focusing on animal rights in the late 1980s, people have become much more aware of issues first highlighted in her work: the immense cruelty of factory farming; the meat industry’s disproportionate consumption of natural resources; the concomitant pollution and degradation of our food supply. In fact, these consciousness-raising efforts have proved so successful that Coe worries animal welfare will come to overshadow animal rights. She does not merely want to improve conditions for food animals, but to end meat consumption altogether. She sees her work as empowering viewers with a simple message: go vegan. “Changing what we eat is one way to do something positive for the environment and to help other people,” Coe says. “We can control what we put into our mouths, what we put into our bodies, and with this starting point, who knows what is possible?”

Käthe Kollwitz and Sue Coe are outliers in the context of an art world that, even in its more rebellious moments, has tended to serve the interests of the powerful. Both artists found niches in genres— printmaking and illustration—that connect directly with the general public but are not heavily contested by men. And as women, each intuitively understood the far-ranging effects of discrimination and oppres- sion. “Women are closer to the heel of the boot,” Coe observes. “They are forced into the roles of being the caretaker, the peacemaker, and as such are the last line of defense for the most vulnerable.”

Rooted in the real world, the art of Käthe Kollwitz and Sue Coe communicates with people in a visual language they understand. Though their styles are very different, both artists combine immediately recognizable representational elements with an expressive abbreviation of form that directly engages the emotions. Kollwitz sometimes spent years refining a single image, trying out variations until she found the most effective synthesis of content and form. “It’s always been a balance of form and content, throughout the history of art,” Coe notes. “The work must achieve a level of technique to convince the viewer to look at the sincerity of the content.” “Admittedly, my art is not ‘pure’ art,” Kollwitz declared. “But art nonetheless.” One-hundred-and-fifty years after the older artist’s birth, the magnitude of her accomplishment still resonates, not just with followers like Coe, but with those of us who know we have yet to achieve equality and justice for all.

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Sibylle von Heydebrand and Daniel Stoll for lending so many of their Kollwitz treasures to our exhibition. This show would not have been possible without their cooperation. The Galerie St. Etienne’s exhibition coordinator, Fay Beilis Duftler, also provided invaluable contributions to the project. Copies of Sue Coe’s latest book (her seventh),

The Animals’ Vegan Manifesto, (122 pages, 115 black & white illustrations, soft-cover) may be purchased for $17.00, plus $10.00 shipping and handling. New York residents, please add sales tax. Checklist entries are accompanied by their catalogue raisonné numbers, where applicable. Image dimensions are given for prints, full dimensions for all other works.

Johannes Vermeer, The Astronomer, 1668, oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des peintures, Acquired by "dation" in 1982. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre)/Franck Raux

Johannes Vermeer, The Astronomer, 1668, oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des peintures, Acquired by "dation" in 1982. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre)/Franck Raux