The Ashmolean 23 March–22 July 2018

The Ashmolean will present a major exhibition of works by American artists that have never before travelled outside the USA (23 March–22 July 2018).

AMERICA’S COOL MODERNISM: O’KEEFFE TO HOPPER will show over eighty paintings, photographs and prints, and the first American avant-garde film, Manhatta, from international collections. Eighteen key loans will come from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and a further twenty-seven pieces are being loaned by the Terra Foundation for American Art with whom the exhibition is organised. Thirty-five paintings have never been to the UK and seventeen of these have never left the USA at all.

COOL MODERNISM examines famous painters and photographers of the 1920s and ‘30s with early works by Georgia O’Keeffe; photographs by Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand and Edward Weston; and cityscapes by Edward Hopper. It also displays the pioneers of modern American art whose work is less well-known in the UK, particularly Charles Demuth (1883–1935) and Charles Sheeler (1883–1965). On show will be major pieces by the so-called precisionist artists.

![I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, Charles Demuth (American, Lancaster, Pennsylvania 1883–1935 Lancaster, Pennsylvania), Oil, graphite, ink, and gold leaf on paperboard (Upson board)]()

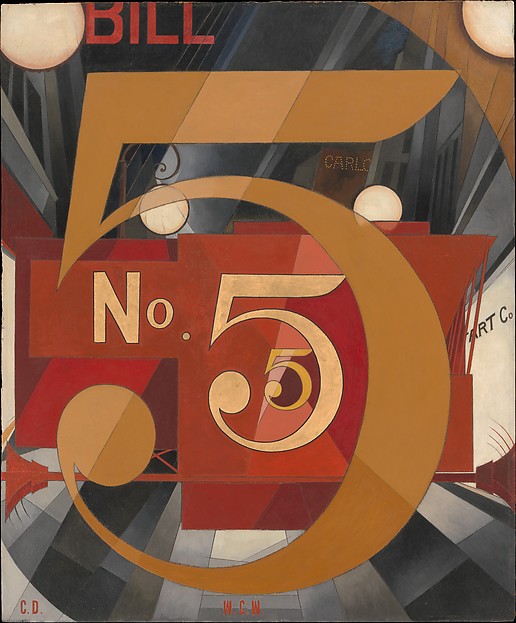

These include Demuth’s I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold (1928, from the Met), the painting Robert Hughes described as the ‘one picture so famous that practically every American who looks at art knows it.’ Made in 1928 and dedicated to the poet William Carlos Williams, the Figure 5, was one of a series of symbolist ‘poster-portraits’ which Demuth made of friends and fellow artists. Consisting of an enormous, stylized ‘5’ that occupies the entire picture plane and painted in bold colours on wallboard, the painting evokes new styles of advertising that were multiplying in American cities in the 1920s – a remarkable anticipation of Pop art later in the century.

![Americana, Charles Sheeler (American, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1883–1965 Dobbs Ferry, New York), Oil on canvas]()

Another important loan is Sheeler’s Americana (1931, from the Met) which has never been lent outside the USA. The painting shows a traditional American domestic scene with Shaker furniture and folk objects arranged in a near abstract composition – a blend of modernist forms with a historical subject.

Other rare loans include a painting by E.E. Cummings (1894–1962), better known for his poetry;

![https://media.nga.gov/public/objects/1/0/9/7/6/6/109766-primary-0-740x560.jpg]()

and Le Tournesol (The Sunflower) (c. 1920, NGA Washington DC) by Edward Steichen (1879–1973) who destroyed nearly all his paintings before dedicating himself to photography. The Sunflower was exhibited in Paris shortly after it was painted in 1922 and has not been seen in Europe since then.

Dr Xa Sturgis, Director of the Ashmolean, says:

‘It is an extraordinary privilege to borrow some of the greatest works ever made by American artists for this landmark exhibition. The Ashmolean is indebted to the Terra Foundation, the Met and other lenders for parting with so many of their treasures. We are bringing together an exceptional collection of paintings, photographs and prints - iconic pieces that have never been to the UK before and deserve to be better-known in this country. We will reveal a fascinating aspect of American interwar art that is yet to be explored in a major exhibition.’

The exhibition looks at a current in interwar American art that is relatively unknown. The familiar story of America in the ‘Roaring Twenties’ is that of The Great Gatsby, the Harlem Renaissance and the Machine Age; while the 1930s are known as the Steinbeckian world marked by the Depression and the New Deal.

This exhibition focuses on the artists who grappled with the experience of modern America with a cool, controlled detachment, eliminating people from their pictures altogether. For some this treatment reflected an ambivalence and anxiety about the modern world. Factories without workers and streets without people could seem strange and empty places.

CATALOGUE

![]()

America's Cool Modernism: O'Keeffe to HopperPaperback

by Katherine Bourgignon(Author), Leo Mazow(Contributor), Lauren Kroiz(Contributor)

![http://www.phillipscollection.org/willo/w/size2/1164w.jpg]()

Two works by Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) from his ‘Migration’ series, which is otherwise full of characters, are notable for the absence of people. They express the harsh experience of African Americans travelling north in hope of a better life. What they found was often more frightening than promising.

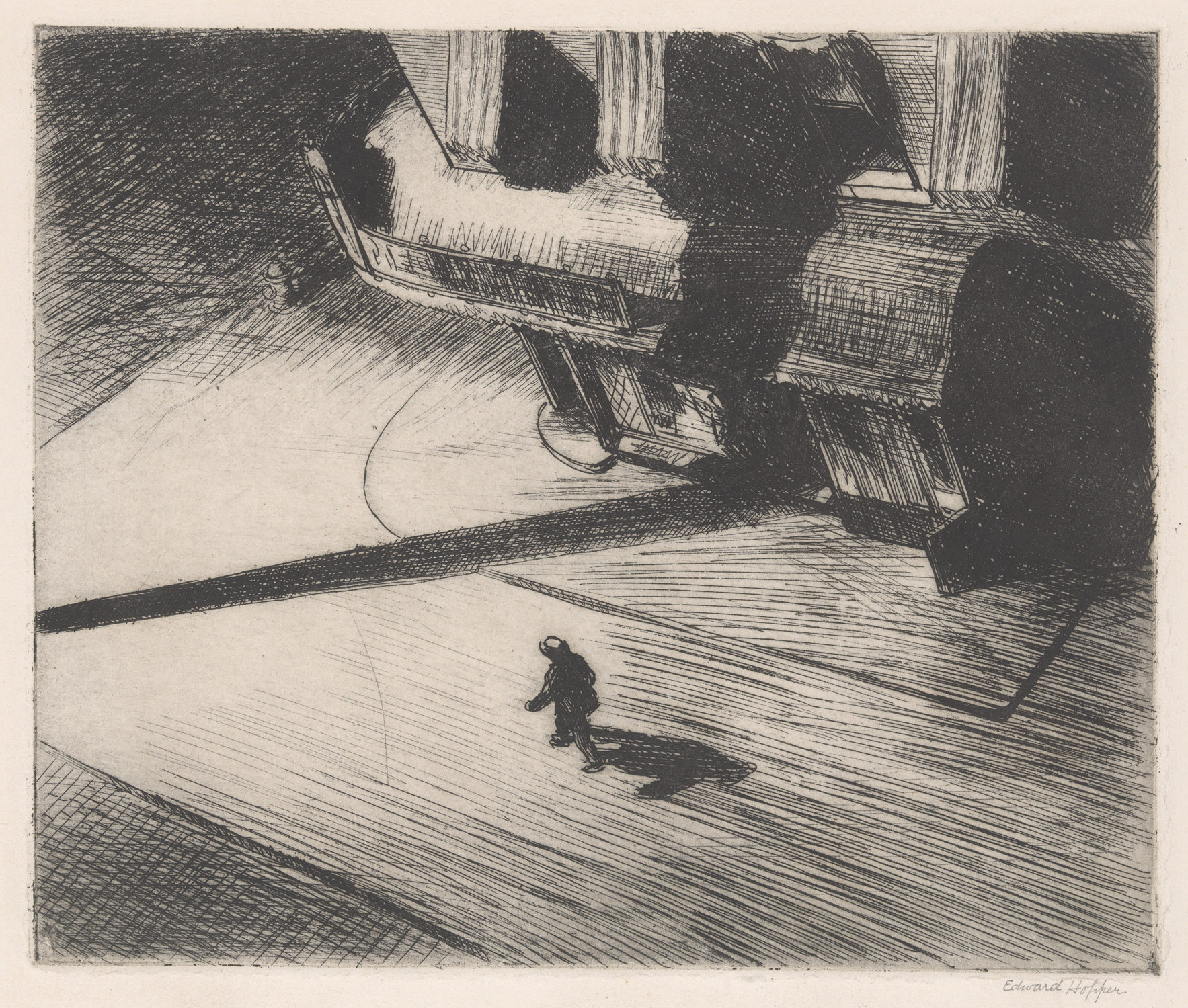

Edward Hopper’s Manhattan Bridge Loop (1928) has a gloomy atmosphere with a tiny, solitary pedestrian whose walking pace is at odds with the bridge’s traffic.

For others, this cool treatment of contemporary America was a positive response - an expression of optimism and pride. Skyscrapers and bridges become studies in geometry; and cities are cleansed and ordered with no crowds and no chaos.

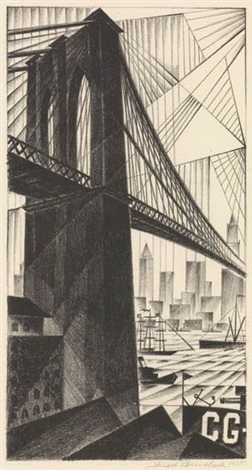

Louis Lozowick’s (1892–1973) prints capture the energy of the city in curving sprawls and buildings soaring into the sky; while Ralston Crawford (1906–78)

and Charles Sheeler depict the architecture of industrial America – factories, grain elevators, water plants – as the country’s new cathedrals, glorious in their scale and feats of engineering, yet oddly emptied of people.

These artists were also engaged in a conscious effort to develop a distinctly American modernism, not derived from Europe but rooted in American cultural tradition and the landscape. They drew a direct line of descent from the simple utilitarian forms of Shaker furniture and rural barns to the standardized, machine-made world of the 1920s and ‘30s. In painting and photographing these subjects in a commensurate style – crisp surfaces, flattened perspective, linear purity - artists and critics were revealing an essential attribute of the American character – modernity.

Dr Katherine Bourguignon, Terra Foundation for American Art and exhibition curator, says:

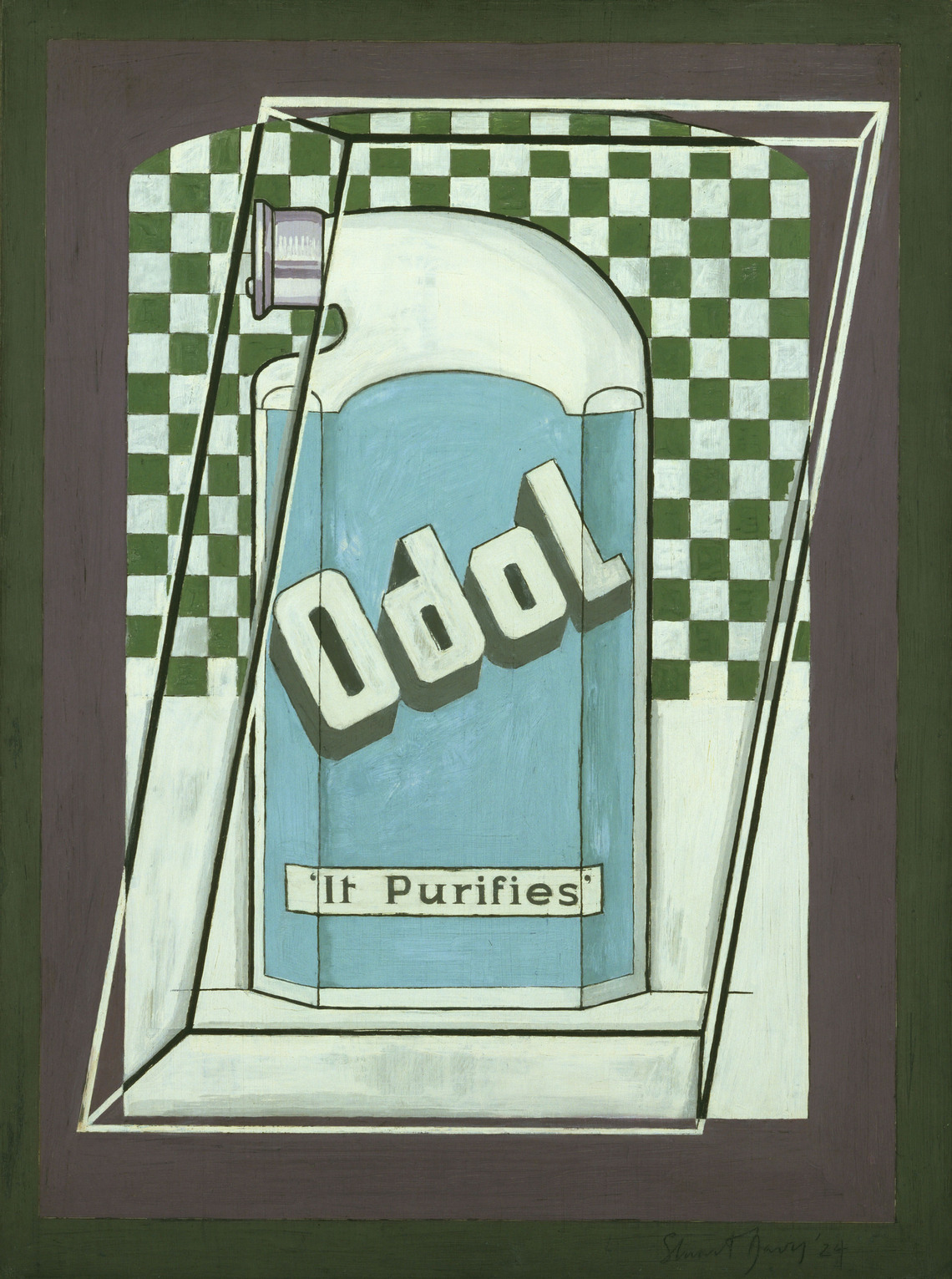

‘In addition to the artists who are well-known in the UK, this exhibition is an opportunity to introduce a European audience to important figures like Patrick Henry Bruce, Helen Torr and Charles Sheeler; and photographers of the interwar period including Imogen Cunningham and Berenice Abbott. These artists were actively seeking to create art that could be seen as authentically ‘American’. Decades before the Pop artists addressed consumerism and the American character, artists in the 1920s and ‘30s were dealing with these themes in remarkably modern images marked by emotional restraint and ‘cool’ control.’

Images

![https://i.pinimg.com/originals/60/8b/d4/608bd4a16890ad1a1f8a4572da695e1a.jpg]()

Marsden Hartley (1877, –, 1943), Painting No. 50, 1914–15, Oil on canvas, 119.4 x 119.4 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,

Edward Steichen (1879, –, 1973), Le Tournesol (The Sunflower), c.1920, Tempera and oil on canvas, 92.1 x 81.9 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, © The Estate of Edward Steichen/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York,

E.E.Cummings (1894, –, 1962), Sound, 1919, Oil on canvas, 89.2 x 88.9 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York , © The Estate of E.E. Cummings,

Patrick Henry Bruce (1881, –, 1936), Peinture, 1917–18, Oil & graphite on canvas, 65.1 x 81.6 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,

Morton Schamberg (1881, –, 1918), Untitled (Mechanical Abstraction), 1916, Oil on composition board, 49.8 x 39.8 cm, © Whitney Museum of Modern Art, New York,

John Covert (1882, –, 1960), Resurrection, 1916, Oil, gesso & pile fabric on plywood, 60.6 x 65.9 cm, © Whitney Museum of Art, New York / estate of the artist,

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887, –, 1986), Black Abstraction, 1927, Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 102.2 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York , © Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York,

![https://fineartamerica.com/images/artworkimages/medium/1/arthur-dove-1880-1946-mountain-and-sky-arthur-dove.jpg]()

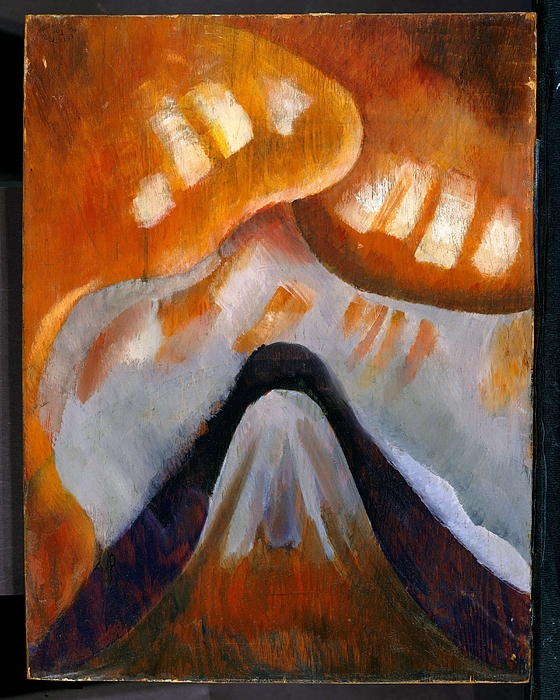

Arthur Dove (1880, –, 1946), Mountain and Sky, c.1925, Oil on wood panel, 39.7 x 30.2 cm, © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Arthur Dove (1880, –, 1946), Goat, 1935, Oil on canvas with selective varnish, 58.4 x 78.7 cm, © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Arthur Dove (1880, –, 1946), Fishboat, 1930, Oil on paperboard nailed to wood strainer, 61.6 x 84.5 cm, © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Arthur Dove (1880, –, 1946), Boat going through Inlet, c. 1929, Oil on tin, 51.4 x 71.8 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Art Acquisition , Endowment Fund, Chicago,

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887, –, 1986), Abstraction, 1919, Oil on canvas, 25.7 x 17.9 cm, The Newark Museum, New Jersey, © Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York,

Arthur Dove (1880, –, 1946), Penetration, 1924, Oil on board, 54 x 44.8 cm, © The Jan T. and Marica Vilcek Collection,

Helen Torr (1886, –, 1967), Purple and Green Leaves, 1927, Oil on copper, mounted on board, 51.4 x 38.7 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© Estate of Helen Torr, with the permission of John and Diane Rehm,

Helen Torr (1886, –, 1967), Crimson and Green Leaves, 1927, Oil on plywood, 35.9 x 31.8 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Estate of Helen Torr, with the permission of John and Diane Rehm,

Paul Strand (1890, –, 1976), Still Life, Pear and Bowls, Twin Lakes, Connecticut, 1916, Printed on Lana Gravure paper, 25.4 x 28.6 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive,

Imogen Cunningham (1883, –, 1976), Magnolia Blossom, 1925, Gelatin silver print, Private Collection, New York, © The Imogen Cunningham Trust, all rights reserved,

Paul Strand (1890, –, 1976), Abstraction, Porch Shadows, Twin Lakes, Connecticut, 1916, Printed on Lana Gravure paper, 30.2 x 20.4 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive,

Berenice Abbott (1898–1991), John Watts Statue: From Trinity Churchyard, Looking toward One Wall , Street, Manhattan,, 1 February 1938, Gelatin silver print, 24.1 x 19.1 cm, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York, © Berenice Abbott, ,

Imogen Cunningham (1883, –, 1976), Fageol Factory, Oakland, 1934, Gelatin silver print, 17.7 x 22.7 cm, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, © The Imogen Cunningham Trust, all rights reserved,

Charles Sheeler (1883, –, 1965), Bucks County Barn, c.1916, Gelatin silver print, 19.1 x 23.9 cm, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, © Estate of Charles Sheeler,

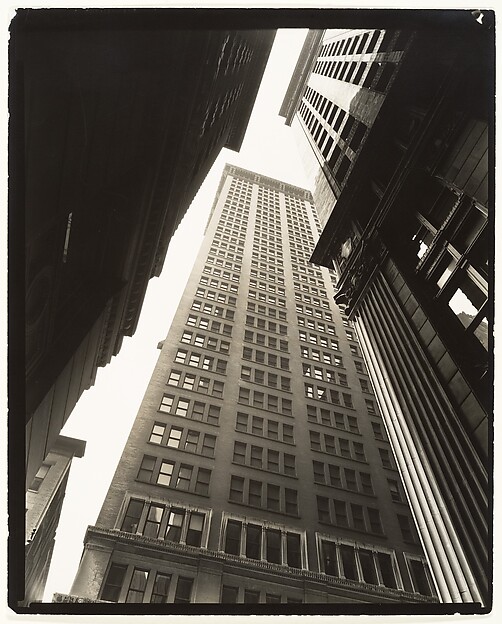

Charles Sheeler (1883, –, 1965), New York, towards the Woolworth Building, 1920, Gelatin silver print, 24.5. x 19.5 cm, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, © Estate of Charles Sheeler,

Alfred Stieglitz (1864, –, 1946), From my window at The Shelton, West, 1931, Gelatin silver print, 23.7 x 19 cm, © George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY,

Paul Strand (1890, –, 1976), Abstraction, Bowls, Twin Lakes, Connecticut, 1936, Photogravure, 22.8 x 16.6 cm, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive,

Paul Strand (1890, –, 1976), The White Fence, Port Kent, New York, 1916 (printed 1917), Photogravure, 16.5 x 21.5 cm, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive,

Charles Demuth (1883, –, 1935), I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, 1928, Oil, graphite, ink and gold leaf on paperboard, 90.2 x 76.2 cm, © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887, –, 1986), East River from The Shelton Hotel, 1928, Oil on canvas, 30.5 x 81.3 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © 2017 Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York,

Imogen Cunningham (1883, –, 1976), Two Calla Lilies, c.1925, Gelatin silver print, 30 x 22.6 cm, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, © The Imogen Cunningham Trust, all rights reserved,

Joseph Stella (1877, –, 1946), Telegraph Poles with Buildings, 1917, Oil on canvas, 92.1 x 76.8 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago , / artist’s estate,

Joseph Stella (1877, –, 1946), Metropolitan Port, 1935–37, Oil on canvas, 89.2 x 74.3 cm, © Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC / artist’s estate,

Oscar Bluemner (1867, –, 1938), Little Falls, New Jersey, 1917, Oil on masonite, , 37.5 x 50.4 cm, © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Charles Sheeler (1883, –, 1965), MacDougal Alley, 1924, Oil on canvas, 66.5 x 52 cm, Davison Art Center Collection, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT, © Estate of Charles Sheeler,

Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), Water, 1945, Oil on canvas, 61 x 74.3 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Estate of

Niles Spencer (1893, –, 1952), Erie Underpass, 1949, Oil on canvas, 71.1 x 91.4 cm, © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York / artist’s estate,

George Ault (1891, –, 1948), Hoboken Factory, 1932, Oil on canvas, 50.8 x 55.9 cm, © Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, , Washington DC / artist’s estate,

Niles Spencer (1893, –, 1952), Waterfront Mill, 1940, Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 91.4 cm, © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York / artist’s estate,

Paul Kelpe (1902, –, 85), Machinery (Abstract #2), 1933–34, Oil on canvas, 97 x 67 cm, © Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC, Charles Sheeler (1883, –, 1965) and

Charles Demuth (1883–1935), Nospmas. M. Egiap Nospmas. M., 1921, Oil on canvas, 61 x 51.4 cm, © Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, New York,

Louis Lozowick (1892, –, 1973), Red Circle, 1924, Oil on canvasboard, 45.7 x 38.1 cm, The Jan T. and Marica Vilcek Collection, © Estate of Louis Lozowick,

Jacob Lawrence (1917, –, 2000), The Migration Series, panel no.25: They left their homes. Soon some, communities were left almost empty., 1940–41, Casein tempera on hardboard, 45.72 x 30.48 cm, The Phillips Collection, Washington DC, © 2016 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle , / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York,

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), The Migration Series, panel no. 31: The migrants found improved housingwhen they arrived north., 1940–41, Casein tempera on hardboard, 30.48 x 45.72 cm, The Phillips Collection, Washington DC, © 2016 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle , / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York,

Arnold Rönnebeck (1885, –, 1947), Brooklyn Bridge, 1925, Lithograph on off-white wove paper, 32.1 x 17 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,

Charles Demuth (1883, –, 1935), Welcome to our City, 1921, Oil on canvas, 63.8 x 51.1 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,

Charles Demuth (1883, –, 1935), Rue du Singe Qui Pêche, 1921, Tempera on academy board, 52.2 x 41 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,

Louis Lozowick (1892, –, 1973), New York, 1925, Lithograph on off-white wove paper, 29.1 x 22.9 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© Estate of Louis Lozowick,

![https://i.pinimg.com/originals/50/07/23/500723f387208d16e1b43752b53636b2.jpg]()

Howard Cook (1901–80), Skyscraper, 1928, Wood engraving on cream Japanese paper, 45.7 x 21.9 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago , / artist’s estate,

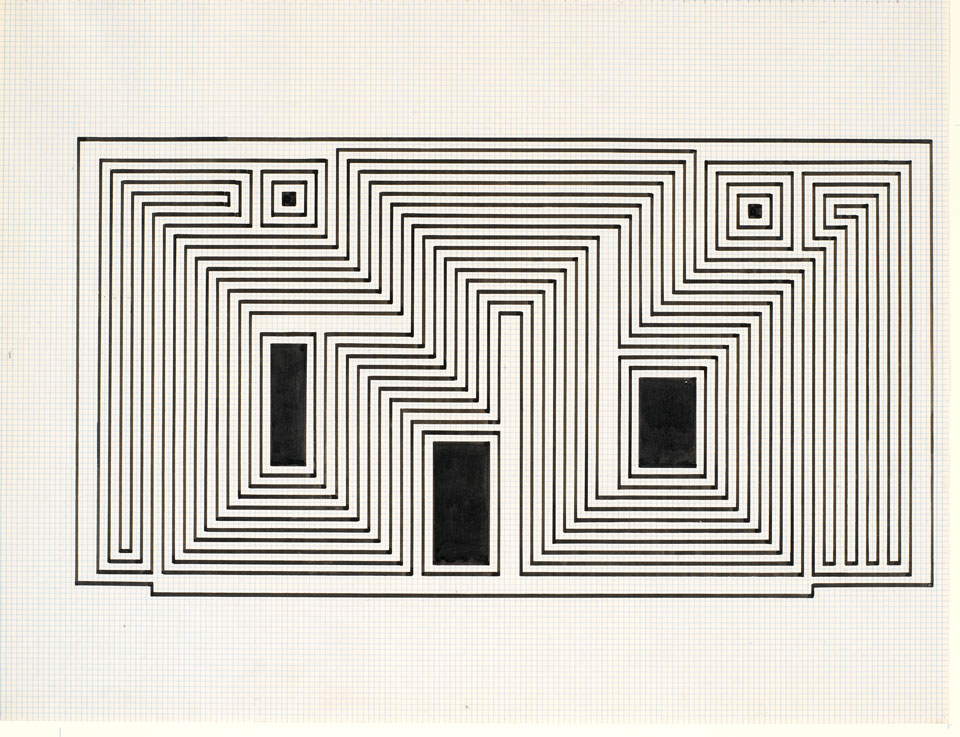

Charles Sheeler (1883, –, 1965), Delmonico Building, 1927, Lithograph on wove ivory paper, 24.8 x 17.1 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© Estate of Charles Sheeler,

Louis Lozowick (1892, –, 1973), Minneapolis, 1925, Lithograph on off-white wove paper, 29.5 x 22.5 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago, © Estate of Louis Lozowick,

John Taylor Arms (1887, –, 1953), The Gates of the City, 1922, Colour etching and aquatint on cream laid paper, 21.6 x 20.2 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago , / artist’s estate

Paul Landacre (1893, –, 1963), The Press, 1934, Wood engraving on wove Japanese paper, 21 x 21 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© The Paul Landacre Estate / VAGA, New York,

Samuel Margolies (1897, –, 1974), Man’s Canyon, 1936, Etching and aquatint on cream laid paper, 30.2 x 22.4 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago , / artist’s estate,

William Charles McNulty (1889, –, 1963), New York in the Fifties, 1931, Drypoint on off-white paper, 34.3 x 17.9 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago , / artist’s estate,

Howard Cook (1901, –, 80), Time Square Sector, 1930, Etching on off-white paper, 30.5 x 25.1 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago , / artist’s estate,

Edward Weston (1886–1958), Steel: Armco, Middletown, Ohio, 1922, Palladium print, Private Collection, New York, © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents,

Paul Strand (1890–1976), From the El, 1915, Platinum print, 33.6 x 25.9 cm, Private Collection, New York, © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive,

Berenice Abbott (1898, –, 1991), Canyon, Broadway and Exchange Place, Manhattan, 1936, Gelatin silver print, Private Collection, New York, © Berenice Abbott,

Charles Sheeler (1883, –, 1965), Coke Ovens-River Rouge, 1927, Gelatin silver print, Private Collection, New York, © Estate of Charles Sheeler,

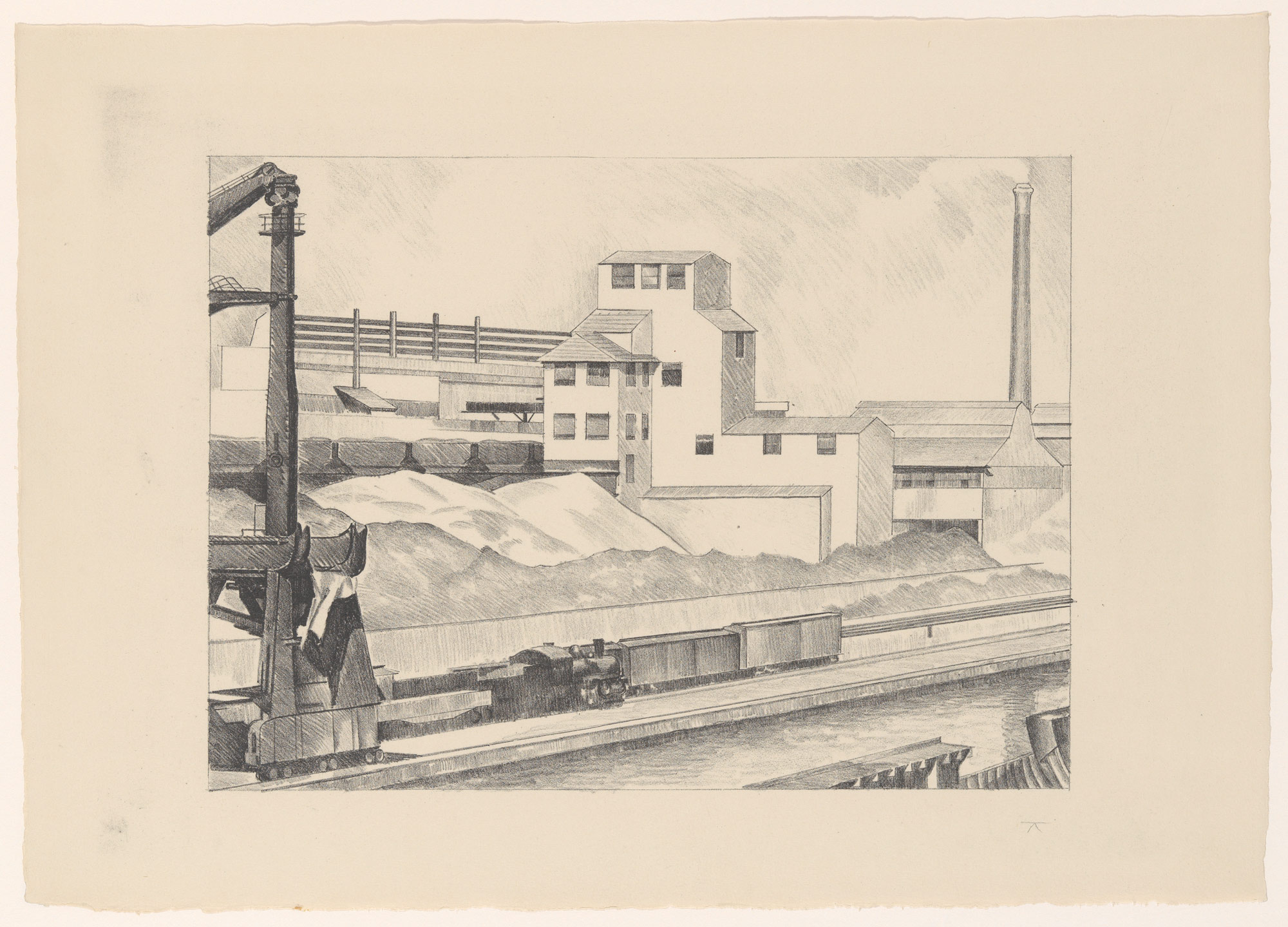

Charles Sheeler (1883, –, 1965), Industrial Series #1, 1928, Lithograph, Private Collection, New York, © Estate of Charles Sheeler,

Ralston Crawford (1906–1978), Buffalo Grain Elevators, 1937, Oil on canvas, 102 x 127.6 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC, © Ralston Crawford Estate,

Charles Sheeler (1883, –, 1965), Bucks County Barn, 1940, Oil on canvas, 46.7 x 72.1 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© Estate of Charles Sheeler,

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Ranchos Church, 1930, Oil on canvas, 61 x 91.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York,

Ralston Crawford (1906–1978), Smith Silo, Exton, 1936–37, Oil on canvas, 76.8 x 91.4 cm, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, © Ralston Crawford Estate,

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Dawn in Pennsylvania, 1942, Oil on canvas, 61.9 x 112.4 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of , American Art,

Stuart Davis (1892–1964), Odol, 1924, Oil on canvas, 60.9 x 45.6 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York, © The estate of Stuart Davis/DACS, London/VAGA, New York 2017,

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Night in the Park , 1921, Etching on white wove paper, 17.3 x 21 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of , American Art,

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), From Williamsburg Bridge, 1928, Oil on canvas, 74.6 x 111.1 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of , American Art,

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Manhattan Bridge Loop, 1928, Oil on canvas, 88.9 x 152.4 cm, Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover MA, © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of , American Art,

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), The Cat Boat, 1922, Etching on off-white wove paper, 20 x 24.9 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago, © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of , American Art,

Martin Lewis (1881–1962), Which Way?, 1932, Aquatint on pale blue paper, 26.2 x 40.3 cm, © Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago , / artist’s estate,

Grant Wood (1891–1942), January , 1938, Lithograph on BFK Rives off-white paper, 22.7 x 30.2 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© Successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/Licensed by VAGA, , New York,

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Night Shadows , 1921, Etching on white wove paper, 17.5 x 21 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of , American Art,

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), The Railroad, 1922, Etching on off-white laid paper, 20 x 25.1 cm, Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, Chicago,© Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of , American Art,

Grant Wood (1891–1942), Fertility, 1939, Lithograph, 22.7 x 30.2 cm, Private Collection, New York, © Successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/Licensed by VAGA, , New York,

Grant Wood (1891–1942), July Fifteenth, 1938, Lithograph on paper, Private Collection, New York, © Successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/Licensed by VAGA, , New York,

Paul Strand (1890–1976), Akeley Motion Picture Camera, New York City, 1923, Gelatin silver print, 24.5 x 19.5 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive

Benton Murdoch Spruance (1904–1967), American Pattern - Barn, 1940, Lithograph, 19.4 x 35.6 cm, © Private Collection, New York / artist’s estate,

'The Bodleian Libraries holds one of the most important collections of medieval manuscripts in the world, and this exhibition celebrates all aspects of the ingenuity and craftsmanship that went into some of the most beautiful, and everyday items that still survive today. The exhibition provides an intriguing and surprising history of English literature in one room.'

'The Bodleian Libraries holds one of the most important collections of medieval manuscripts in the world, and this exhibition celebrates all aspects of the ingenuity and craftsmanship that went into some of the most beautiful, and everyday items that still survive today. The exhibition provides an intriguing and surprising history of English literature in one room.'