Nearly eighty masterpieces of Italian Renaissance drawing from Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, including a number of rarely seen works, were on view only at The Morgan Library & Museum from January 25 through April 20, 2008.

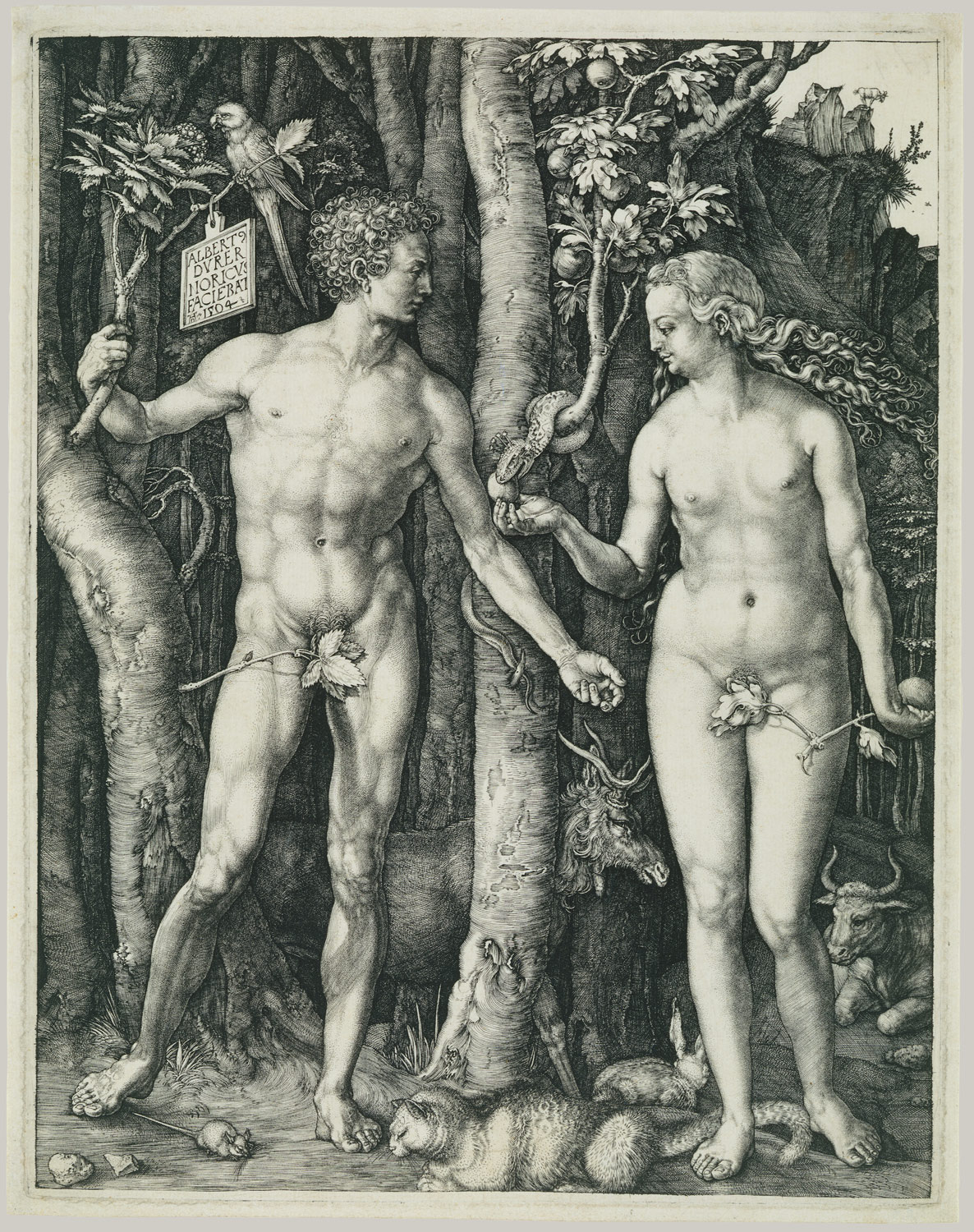

Michelangelo, Vasari, and Their Contemporaries: Drawings from the Uffizi surveyed the work of renowned masters who defined Florentine draftsmanship. The exhibition focused on works by important artists who participated in a major campaign of redecorating the famed

Palazzo Vecchio, one of the most impressive buildings in Renaissance Florence and the focal point of artistic activity throughout the sixteenth century.

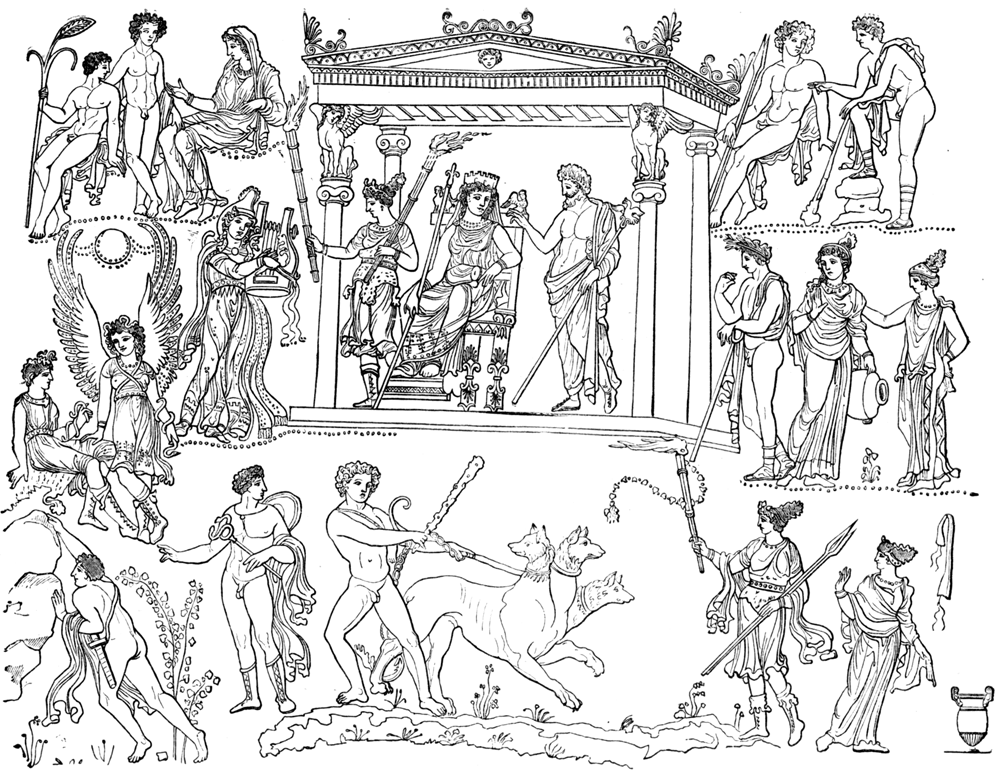

Under the auspices of Cosimo I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, (1519–74), this former city hall was transformed by the leading artists of the time into a palatial residence and an icon of Medici Florence. The artist-historian Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) acted as the mastermind and creative director of the complex and varied decorations for the palazzo, choosing as his collaborators the most talented painters in Florence. The exhibition demonstrates how drawing functioned not only as a means of planning the elaborate paintings, frescoes, and tapestries needed for the refurbishment of the palazzo, but also as a tool that facilitated the creative process for Vasari and his contemporaries.

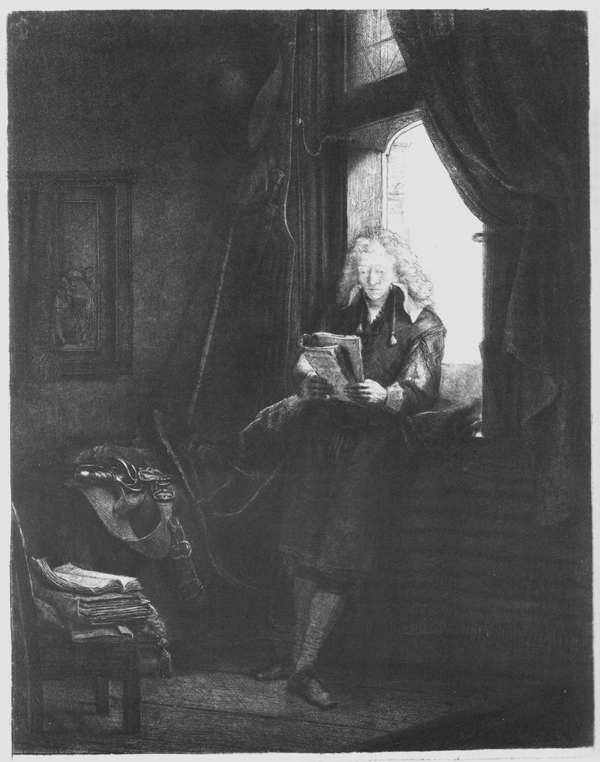

![]()

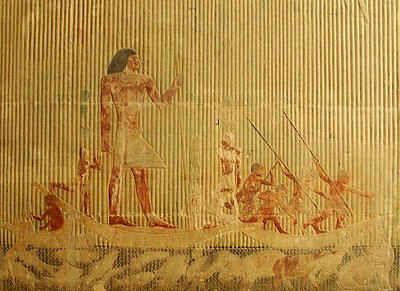

Pontormo, Two Studies of Male Figures ; (1521). Black chalk and red chalk, red wash, heightened with white chalk. Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi.

PALAZZO VECCHIO

Palazzo Vecchio was built as the government headquarters of Florence during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. After Duke Cosimo I came to power in 1537 through a series of tense political machinations, the young ruler soon established his authority and significantly expanded Florentine territories and influence. A strong personality with a clear vision for his dukedom, Cosimo I moved his family from the traditional Medici residence to Palazzo Vecchio as a calculated gesture to confirm his identification with the state.

Cosimo I employed the arts as a means of demonstrating his absolute power. His decision to completely renovate and expand the palazzo was designed to exalt his status as sovereign against an extraordinarily prestigious backdrop. Historically, only the most respected artists and intellectuals had been involved with the palazzo’s alterations, and Cosimo’s campaign was no exception. Florence’s leading painters, sculptors, and architects were called upon to demonstrate their talents in the redecoration of the city’s historical and symbolic center, simultaneously glorifying their ruler as well as their own artistic endeavors.

THE ARTISTS

The exhibition was divided into three sections highlighting the artists who shaped the nature of Italian Renaissance drawing and contributed to the palazzo’s decorations under Duke Cosimo I.

The first section, “The Great Masters,” showcased the artists who directly preceded Vasari’s intervention in the palazzo and served as great artistic examples for subsequent generations. Michelangelo (1475–1564), who had already sculpted his masterpiece, the statue of David, for the palazzo and competed with Leonardo in the decoration of the palazzo’s main hall, was one of the preeminent models for Vasari and his collaborators. His black-chalk masterpiece, the

![]()

Bust of a Woman,

one of the so-called Divine Heads, exerted a tremendous influence on Florentine draftsmanship, and his sheet with studies of legs exemplifies his perfect anatomical constructions.

Andrea del Sarto (1486-1531), a guiding force in the history of Italian Renaissance art, also figured prominently in the exhibition with a red chalk Study of a Male Model, preparatory for his painting of the Madonna of the Stairs from the 1520s, and with a rare compositional study of high drama and emotional intensity, the

![]()

Lamentation of Christ.

Additionally, mannerist masters Pontormo (1494–1557), Rosso Fiorentino (1494–1540), Francesco Salviati (1510–1563), and Bronzino (1503–1572) were represented by exquisite examples of their graphic work. Michelangelo, Vasari, and Their Contemporaries: Drawings from the Uffizi

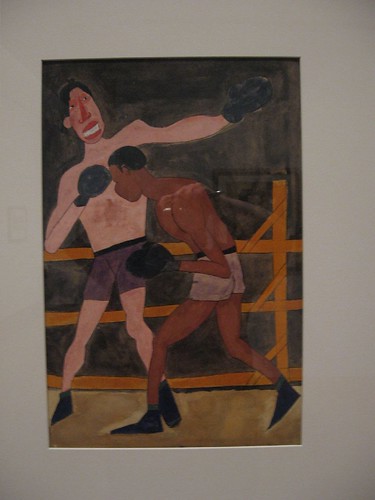

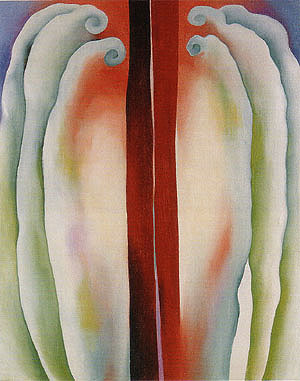

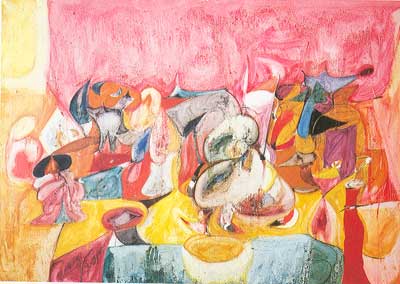

![]()

Pontormo’s vibrant study of Seated Male Figures

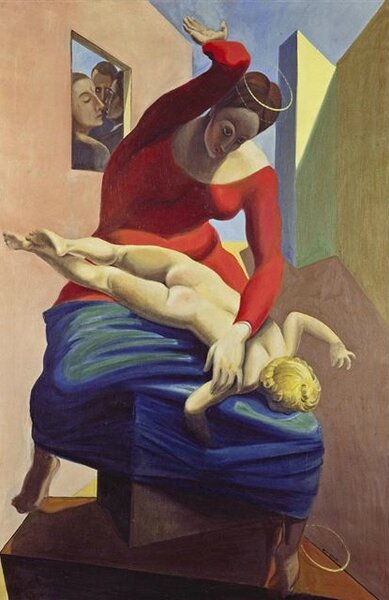

records his method of studying a live model’s movements to exceptional effect, and Rosso’s masterful yet highly personal approach to drawing is evident in his

![]()

Virgin and Child with Four Saints,

presumably a study for this oil painting:

![]()

Also on view were Bronzino’s meticulously rendered preparatory study for one of the nearly life-size figures that adorn the private chapel of Cosimo I’s wife Eleonora of Toledo (1522–1562) in the Palazzo Vecchio, and

![]()

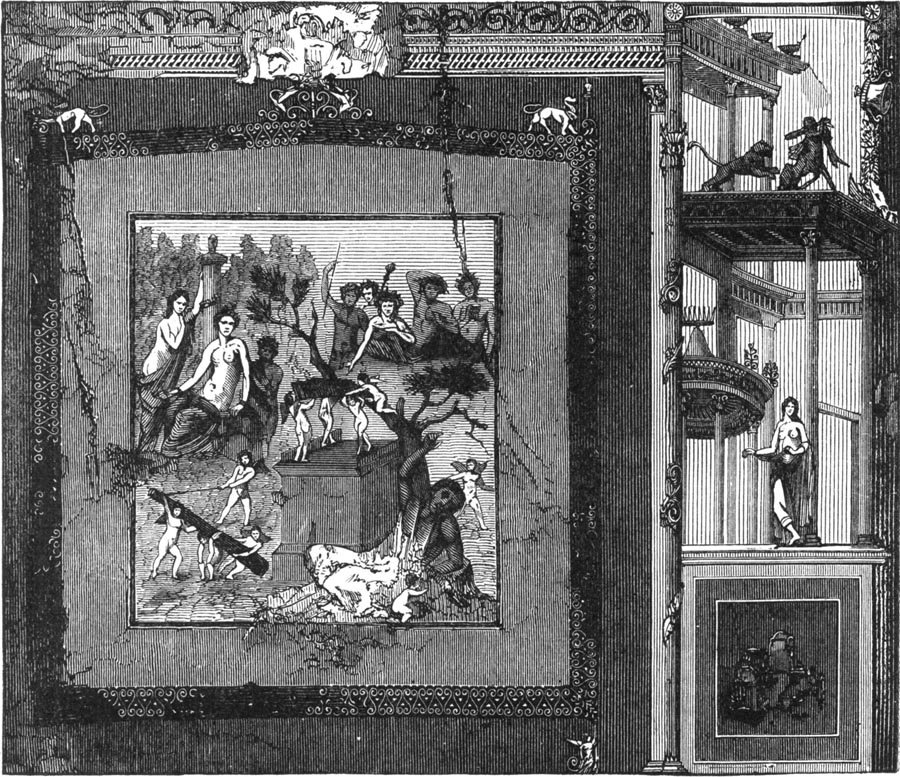

Salviati’s great graphic masterpiece, a tapestry design of The Age of Gold.

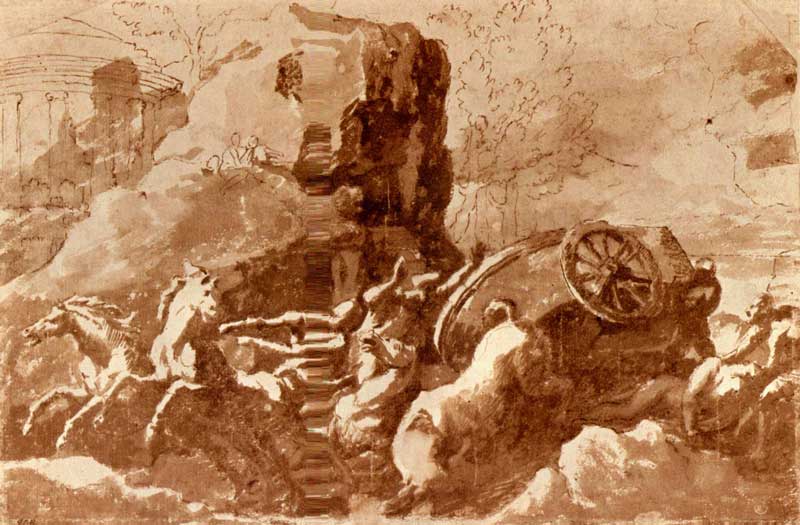

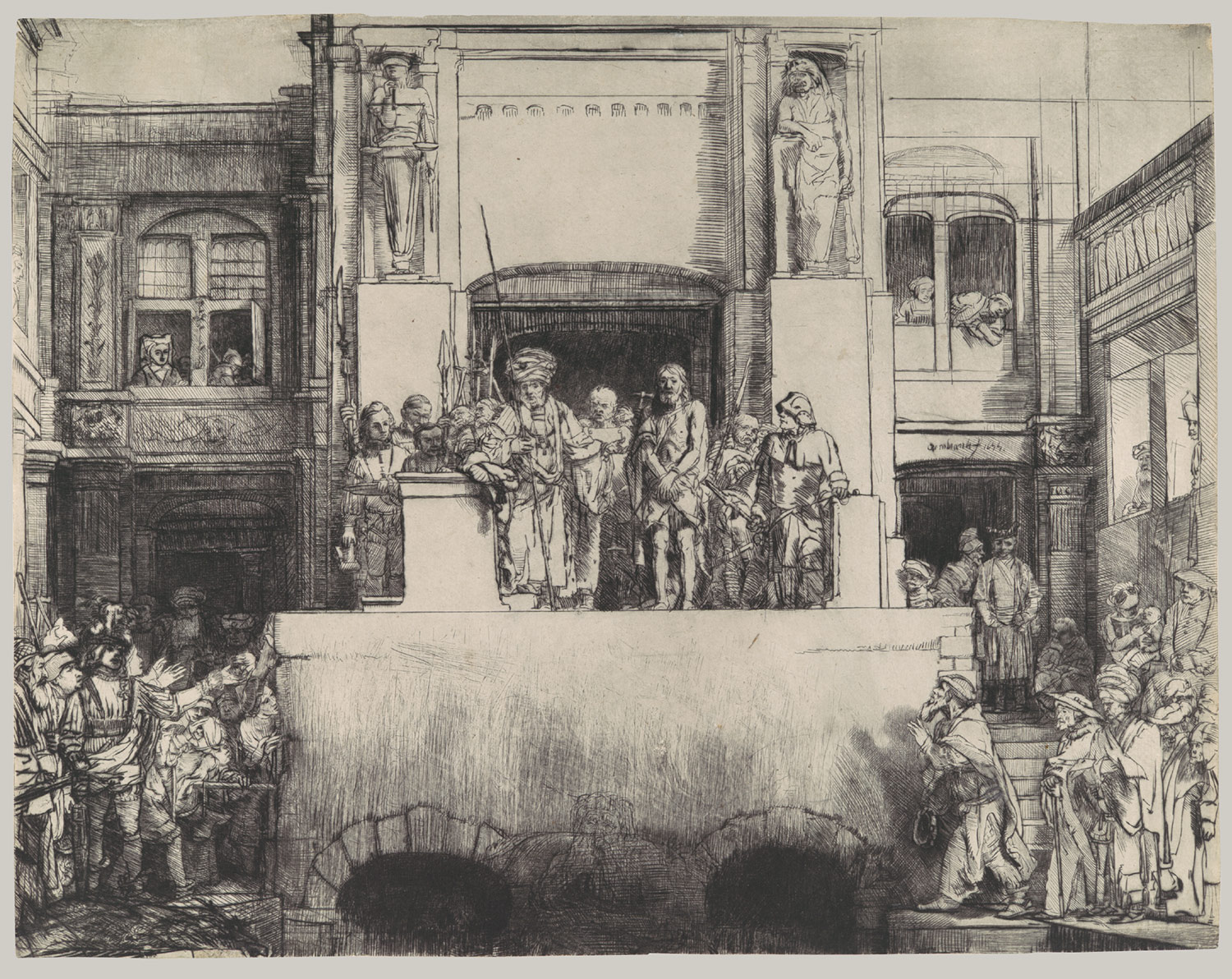

The second section of the exhibition, “Vasari and His Collaborators,” focused on Vasari’s own drawings as well as those of his collaborators in the various rooms of the palazzo, in particular the magnificent Salone dei Cinquecento (Hall of the Five Hundred). Under Vasari’s direction, artists such as Alessandro Allori (1535–1607), Bernardo Buontalenti (1513–1608), Giovanni Stradanus (1523–1605), Santi di Tito (1536–1603), and Giovan Battista Naldini (1537–1591) collaborated on expansive painted scenes commemorating the duke’s military exploits as well as the Medici’s illustrious ancestors. Among Vasari’s drawings on view was an exceptional compositional study of The Siege of Milan for the Room of Leo X and a design for the Salone dei Cinquecento.

The final portion of the exhibition, “The Painters of the Studiolo,” showcased drawings by painters of the celebrated Studiolo of Francesco I de’ Medici, Cosimo’s heir. Included were studies by late mannerist artists such as Girolamo Macchietti (1535–1592), Maso da San Friano (1531–1571) and Poppi (1544–1597).

From

Intelligent Life:I am amazed by the complicated flickering composition of Rosso Fiorentino's "Virgin and Child with SS. John the Baptist, Margaret, and Sebastian and an Elderly Male Saint (Joseph?)" from 1522-5, in black chalk and gray wash.

Ditto for the solid, sculptural muscularity (beefcake, again) of the

![]()

"Male Nude Seen From Behind" by Bronzino in 1540-6,

every arched muscle illuminated--the shadows creating an impossible stone texture.

I can hold a pen, but I know my pen stroke could never create the flutter of the

![]()

"Punishment of Titius", done by Poppi (a Michelangelo copy) in which the agitated bird flies down in feathered strokes on the softly moulded writhing figure, which may very well be as delicate and beautiful as the Michelangelo original.

It goes without saying that the drawings on view are not simply life drawings, or copies of other works. In this show drawing from life meets that special, master Mannerist edge. As Holland Cotter said in the New York Times, "everyone wanted to make art this good and this strange".

Michelangelo's bizarrely polished masculine figures and limbs sit across from a quick sketch by Pontormo, "Two Studies of Male Figures" from 1521, in which the males in question look like crash-test dummies, twisting and turning in heavy charcoal strokes, emerging from the chaos of the page.

From ArtTattler:

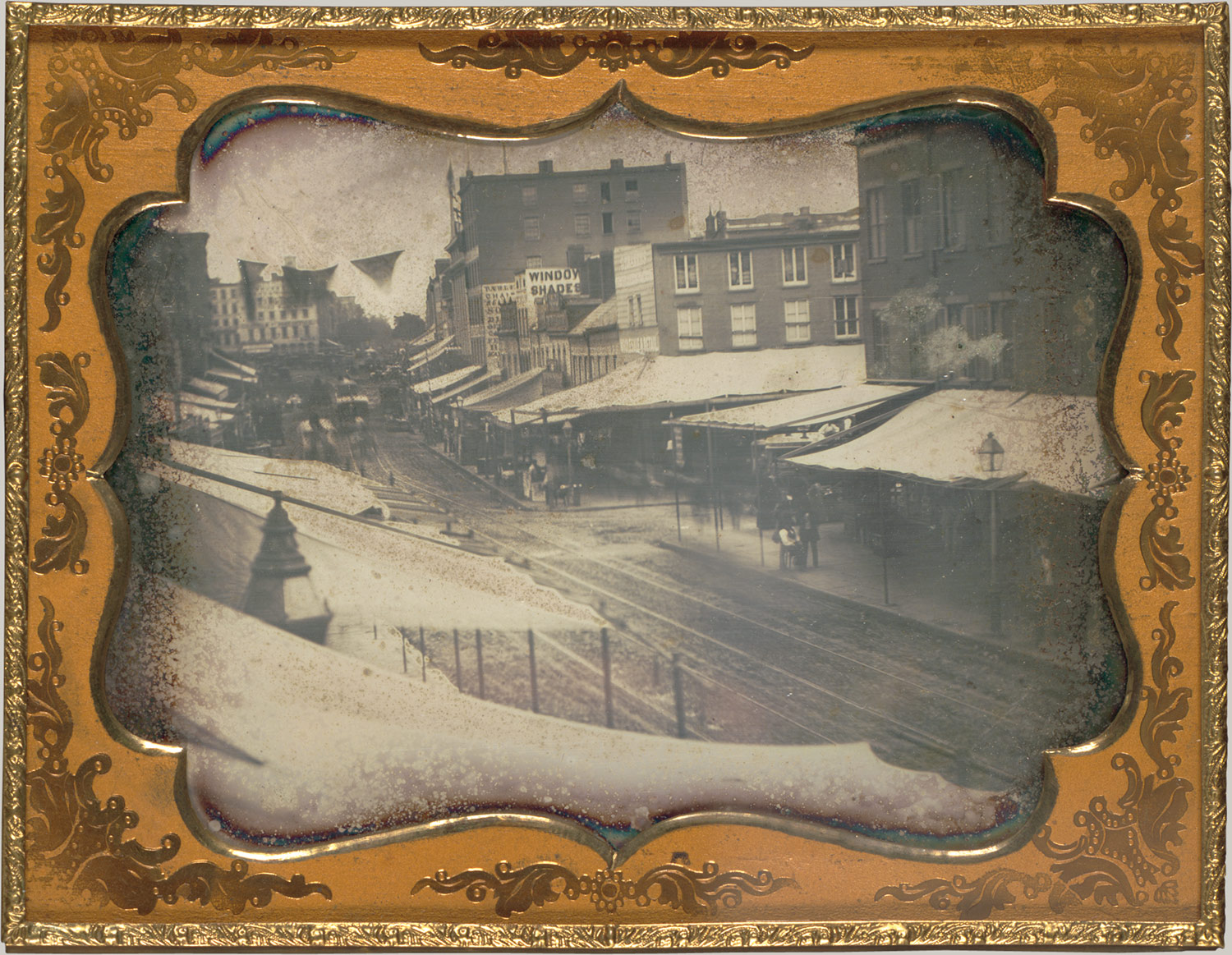

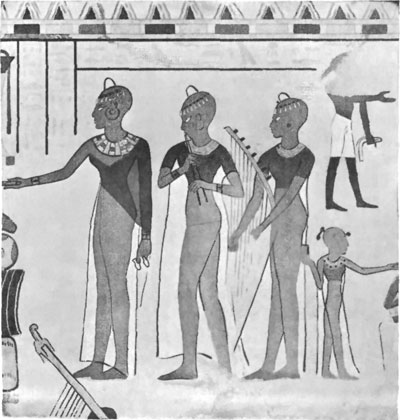

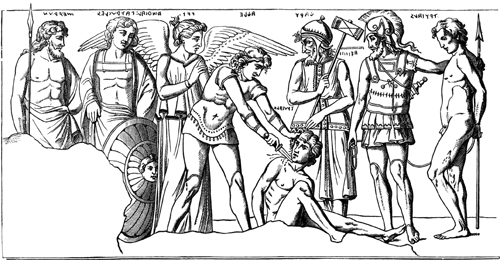

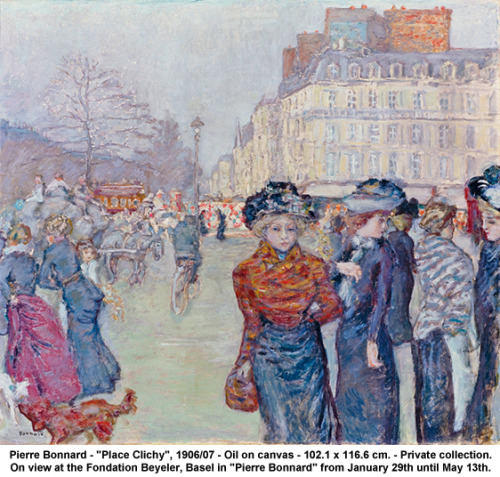

![]()

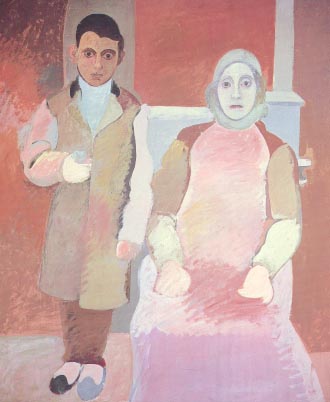

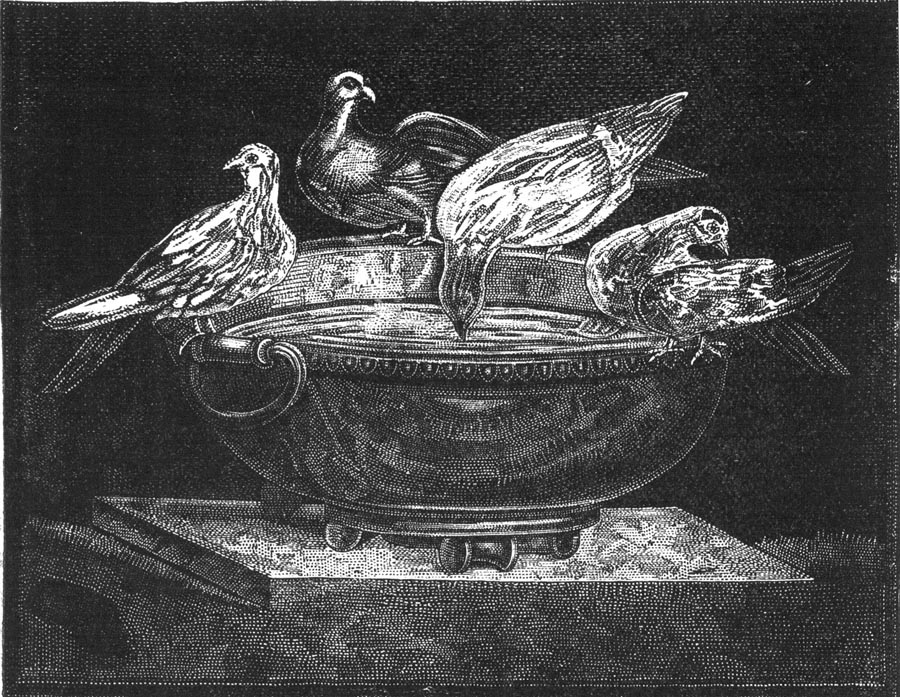

An important figure in the transition between mannerism and the baroque period at the end of the sixteenth century, Santi di Tito emphasized in his works a narrative clarity and simplicity of expression. This preparatory drawing is for a fresco in a chapel dedicated to St. Luke, the patron saint of the arts, in the church of Santissima Annunziata in Florence. Intended as an allegorical representation of architecture, its subject employs the story of Solomon directing the building of the temple, presented in a straightforward composition that directs the viewer’s eye to the main figures elegantly highlighted in brilliant white.

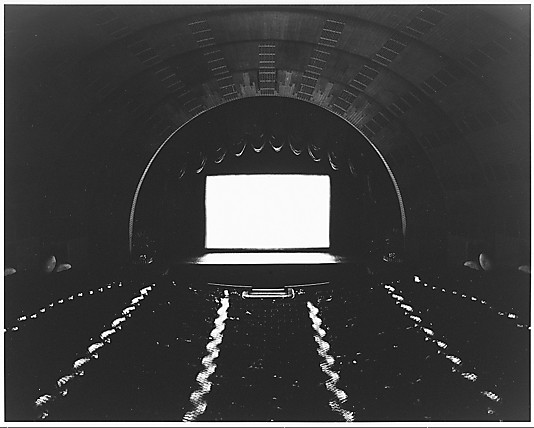

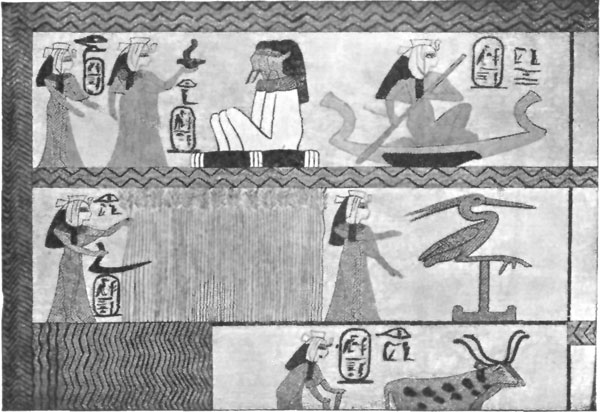

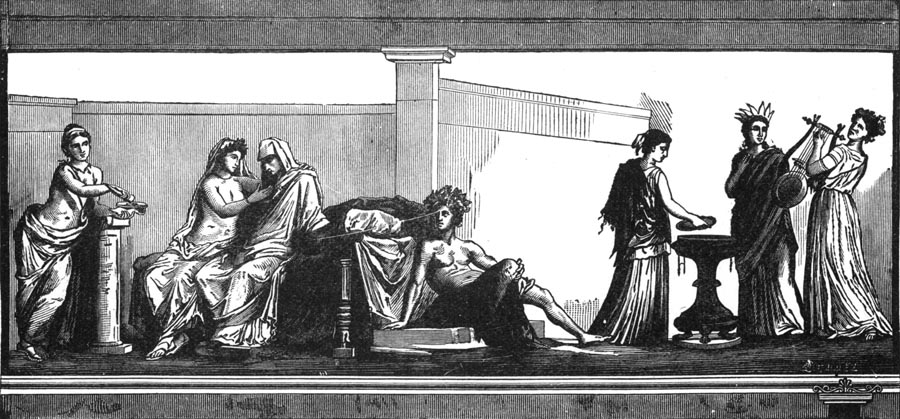

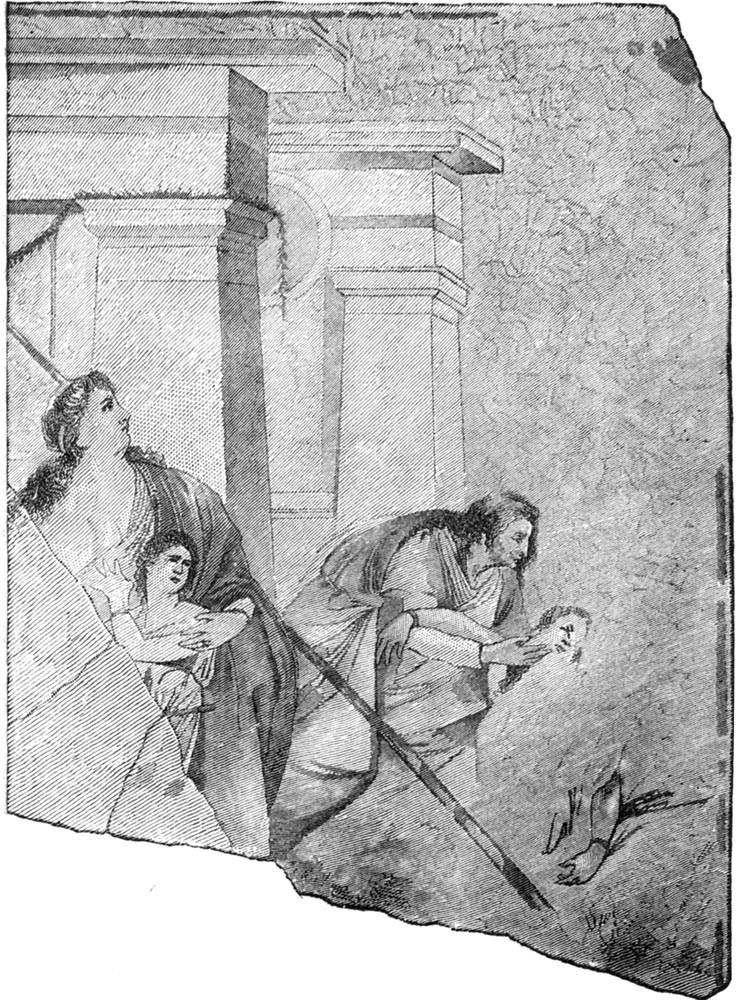

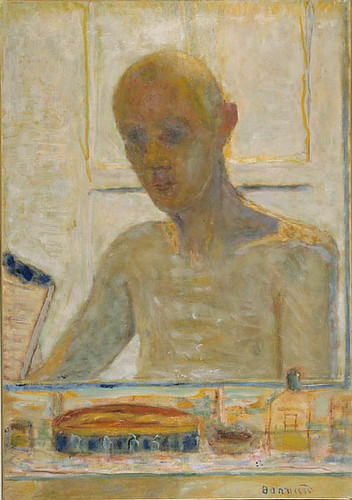

![]()

Known as the first chronicler of the lives of Renaissance artists, Vasari had a prominent career as artist to both the Medici court in Florence and the papal court in Rome. This drawing comes from one of the most important commissions of Vasari’s career: Pope Julius III hired him to oversee the design and construction of his family’s funerary chapel in Rome, a project supervised by Michelangelo. Probably a study for the figure of John the Evangelist, this drawing displays Vasari’s exceptional ability to conjure a figure in his mind and transfer it flawlessly to paper.

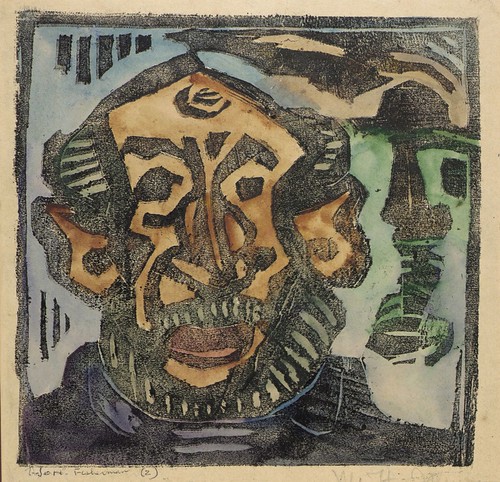

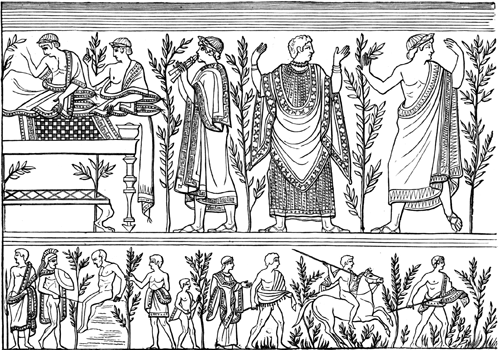

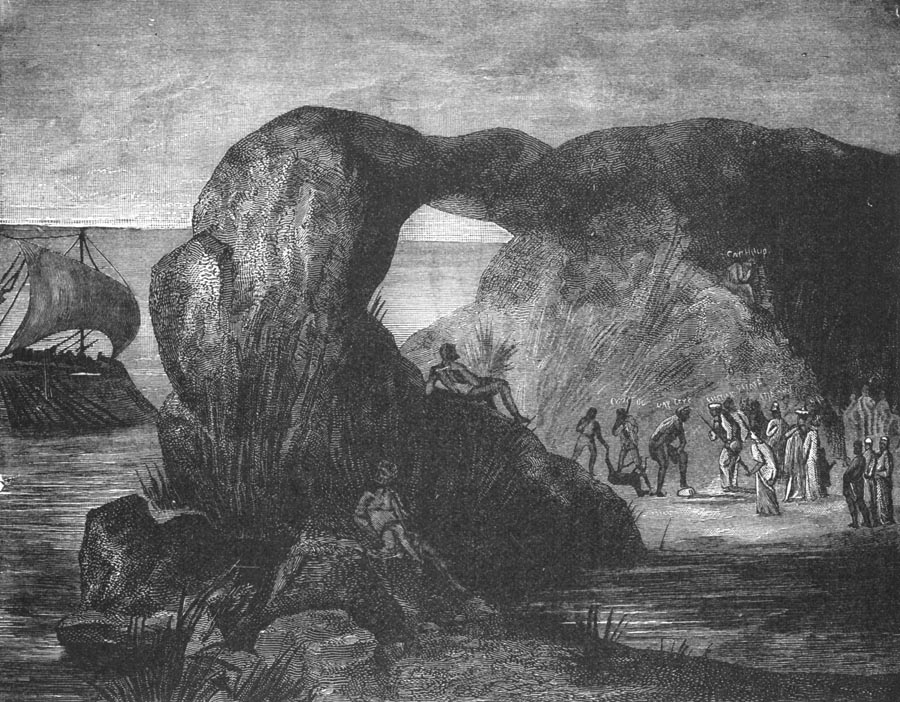

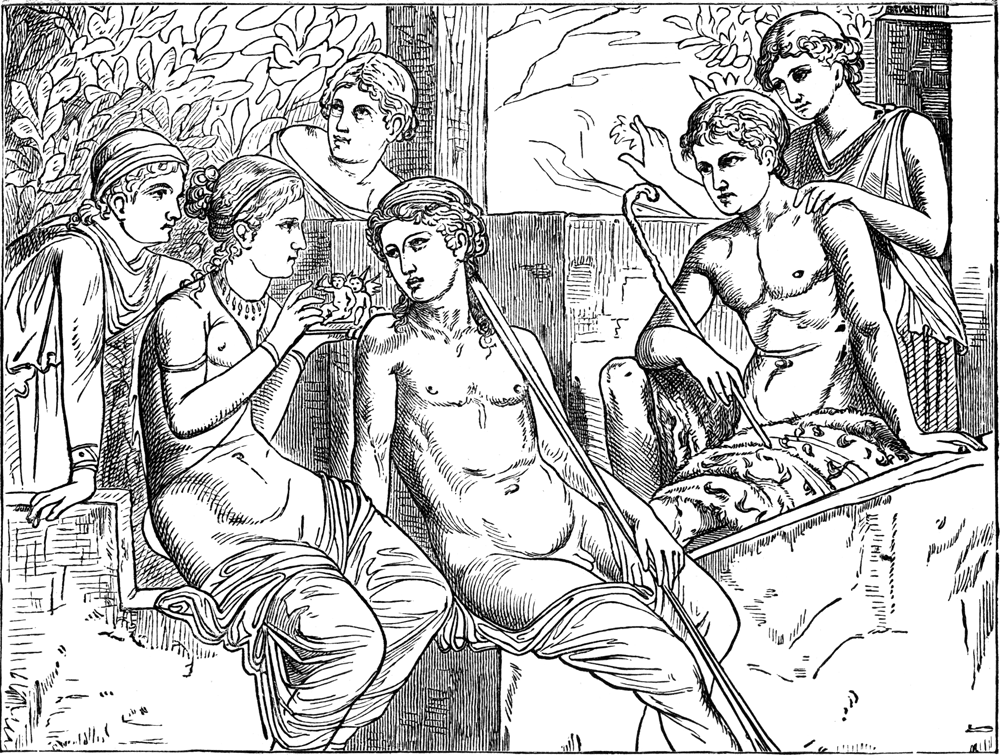

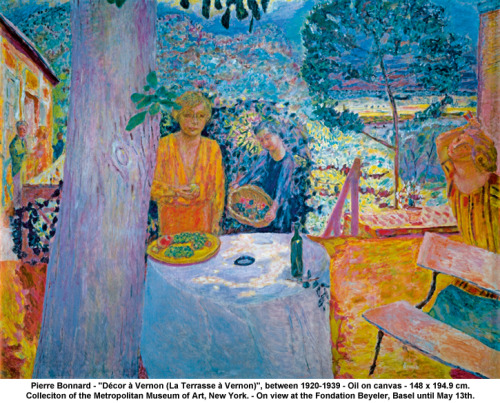

![]()

Trained by Bronzino and deeply familiar with Michelangelo’s sculpture, Allori was often commissioned to supply designs for the ducal tapestry workshop. This detailed representation of a crowd paying homage to Bacchus is the only preparatory drawing that survives from a series intended as models for tapestries with scenes from Bacchus’s life. Finely executed in a wide variety of techniques, this is a typical example of the increasing interest in exuberant decoration that characterized Florentine draftsmanship of the later sixteenth century.

More images and comments here and

here.

The exhibition was organized by special arrangement with the Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale fiorentino and the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi and was conceived by Annamaria Petrioli Tofani, former director of the Uffizi. It will only be shown in New York and is curated by Rhoda Eitel-Porter, Charles W. Engelhard Curator and department head of Drawings and Prints, The Morgan Library & Museum.

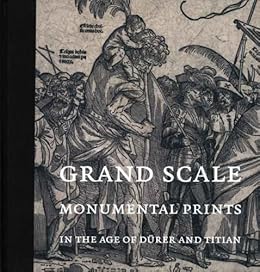

CATALOGUE

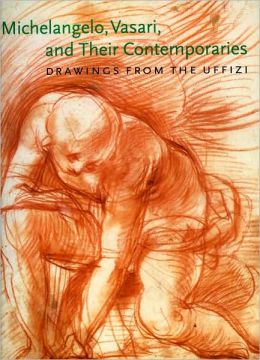

![]() Michelangelo, Vasari, and Their Contemporaries: Drawings from the Uffizi

Michelangelo, Vasari, and Their Contemporaries: Drawings from the Uffizi was accompanied by a catalogue written by Annamaria Petrioli Tofani with contributions by Rhoda Eitel-Porter.

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST

The Great Masters

Michelangelo Buonarroti CAPRESE, FLORENCE, 1475–1564 ROME

Studies of a Male Leg (recto and verso)

Metalpoint (lead?)

342 x 280 mm (13 7/16 x 11 in.)

Inv. 18719

Michelangelo Buonarroti CAPRESE, FLORENCE, 1475–1564 ROME

Bust of a Woman, Head of an Old Man, and Bust of a Child

Verso: Male Heads and Other Studies

Black chalk

357 x 252 mm (14 1/10 x 9 15/16 in.)

Inv. 598

Andrea del Sarto (Andrea d’Agnolo) FLORENCE 1486–1530 FLORENCE

Studies of a Male Model Seated on the Ground

Verso: Study of Drapery

Red chalk and red wash

265 x 200 mm (10 7/10 x 7 7/8 in.)

Inv. 318

Andrea del Sarto (Andrea d’Agnolo) FLORENCE 1486–1530 FLORENCE

Lamentation of Christ

Black chalk and gray wash

Inscribed at lower center, in pen and brown ink di mano dandrea del Sarto

276 x 226 mm (10 7/8 x 8 7/8 in.)

Inv. 642

Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci) PONTORMO, EMPOLI, 1494–1556 FLORENCE

Two Studies of Male Figures

Verso: Seated Nude Boy

Black and red chalk, red wash, heightened with white chalk; verso: red chalk

285 x 408 mm (11 1/4 x 16 1/16 in.)

Inv. 6740

Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci) PONTORMO, EMPOLI, 1494–1556 FLORENCE

Male Nude Seen from Behind and Study of a Head

Verso: Study of a Male Nude

Black chalk on paper tinted pink; verso: black chalk

225 x 165 mm (8 7/8 x 6 1/2 in.)

Inv. 6593 F

Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci) PONTORMO, EMPOLI, 1494–1556 FLORENCE

Eve’s Expulsion from Earthly Paradise

Black chalk

291 x 210 mm (11 7/16 x 8 1/4 in.)

Inv. 6715

Rosso Fiorentino (Giovan Battista di Jacopo) FLORENCE 1494–1540 PARIS

Virgin and Child with SS. John the Baptist, Margaret, and Sebastian and an Elderly Male Saint (Joseph?)

Black chalk and gray wash

331 x 253 mm (13 x 19 15/16 in.)

Inv. 479

Rosso Fiorentino (Giovan Battista di Jacopo) FLORENCE 1494–1540 PARIS

Nude Woman Standing with One Arm Above Her Head

Red chalk, with traces of black chalk

365 x 176 mm (14 3/8 x 6 15/16 in.)

Inv. 6478

Andrea di Cosimo Feltrini FLORENCE 1477–1548 FLORENCE

Study for a Grotesque

Black chalk

171 x 283 mm (6 3/4 x 11 1/8 in.)

Inv. 143

Baccio Bandinelli FLORENCE 1493–1560 FLORENCE

Hercules Standing

Red chalk

405 x 197 mm (15 15/16 x 7 3/4 in.)

Inv. 520

Baccio Bandinelli FLORENCE 1493–1560 FLORENCE

Hercules and Cacus

Verso: Studies of Heads and Arms

Pen and brown ink (recto and verso)

399 x 282 mm (15 11/16 x 11 1/8 in.)

Inv. 714

Baccio Bandinelli FLORENCE 1493–1560 FLORENCE

Portrait of Duke Cosimo dei Medici

Black chalk, stumped

268 x 204 mm (10 9/16 x 8 in.)

Inv. 15010

Baccio Bandinelli FLORENCE 1493–1560 FLORENCE

Christ Shown to the People (Ecce Homo)

Pen and brown ink, with traces of black chalk

424 x 566 mm (16 11/16 x 22 1/4 in.)

Inv. 705

Bacchiacca (Francesco Ubertini) BORGO SAN LORENZO 1494–1557 FLORENCE

A Goat Being Milked

Verso: A Barking Dog

Black chalk, stumped, pricked for transfer; verso: black chalk, stumped

228 x 116 mm (9 x 4 9/16 in.)

Inv. 1927

Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo) FLORENCE 1503–1572 FLORENCE

Male Nude Seen from Behind

Black chalk, with gray wash, on paper tinted yellow ochre

422 x 165 mm (16 5/8 x 6 1/2 in.)

Inv. 6704

Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo) FLORENCE 1503–1572 FLORENCE

Study of Two Nude Half Figures and a Right Arm

Verso: Studies of Figures and Drapery

Black chalk, with touches of gray wash; verso: black chalk

322 x 247 mm (12 11/16 x 9 3/4 in.)

Inv. 10320

Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo) FLORENCE 1503–1572 FLORENCE

Flying Putti

Black chalk, stumped

263 x 184 mm (10 3/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

Inv. 570

Attributed to Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo) FLORENCE 1503–1572 FLORENCE

Half-Length Portrait of a Gentlewoman

Red chalk, red wash, with traces of white chalk

391 x 267 mm (15 3/8 x 10 1/2 in.)

Inv. 414

Francesco Salviati (Francesco de’ Rossi) FLORENCE 1510–1563 ROME

The Allegory of Fortune

Black chalk

457 x 296 mm (18 x 11 5/8 in.)

Inv. 609

Francesco Salviati (Francesco de’ Rossi) FLORENCE 1510–1563 ROME

The Age of Gold

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white gouache, over traces of black chalk

414 x 533 mm (16 5/16 x 21 in.)

Inv. 1194

Francesco Salviati (Francesco de’ Rossi) FLORENCE 1510–1563 ROME

A Seminude Youth with a Bow in His Right Hand

Red chalk, with traces of red wash

415 x 238 mm (16 5/16 x 9 3/8 in.)

Inv. 538 S

Bernardo Buontalenti FLORENCE 1513–1608 FLORENCE

Lunette with the Coat of Arms of Cosimo I dei Medici and Eleonora of Toledo

Verso: Lunette with the Medici Coat of Arms

Red chalk, pricked for transfer, on paper darkened by pouncing; verso: pen and brown ink, over black chalk

291 x 537 mm (11 7/16 x 21 1/8 in.)

Inv. 427

Vasari and His Collaborators

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

The Damned Soul (After Michelangelo)

Black chalk

232 x 198 mm (9 1/8 x 7 13/16 in.)

Inv. 18738

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

A Prophet

Pen and brown ink

284 x 167 mm (11 3/16 x 6 9/16 in.; original sheet, trimmed and laid down on secondary support)

Inv. 1207 S

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

Allegory of Charity

Pen and brown ink, with gray wash, heightened with white gouache, over traces of black chalk, on paper tinted yellow-ochre

413 x 250 mm (16 1/4 x 9 13/16 in.)

Inv. 1071 S

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

Study for the Decoration of a Loggia

Pen and brown ink, with brown wash, over traces of black chalk

294 x 479 mm (11 9/16 x 18 7/8 in.)

Inv. 1618

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

Study for the Decoration of a Ceiling with Virtue Overcoming Fortune and Envy

Pen and brown ink, with brown wash, over traces of black chalk

448 x 368 mm (17 5/8 x 14 1/2 in.)

Inv. 1617

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

Pietà

Pen and brown ink, over traces of black chalk

417 x 305 mm (16 7/16 x 12 in.)

Inv. 625

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

Study for a Frontispiece

Pen and brown ink

265 x 196 mm (10 7/16 x 7 3/4 in.)

Inv. 394

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

St. John the Evangelist

Black chalk

353 x 253 mm (13 7/8 x 9 15/16 in.)

Inv. 14274

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

Studies of Male Figures

Black chalk

212 x 364 mm (8 3/8 x 14 5/6 in.)

Inv. 13844

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

The Florentine Victory over Milan

Pen and brown ink, light brown wash, over black chalk, squared in black chalk

427 x 368 mm (16 13/16 x 14 1/2 in.)

Inv. 626

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

Male Figure Seated on a Stool

Black chalk, heightened with white gouache, on grayish green paper

364 x 212 mm (14 5/16 x 8 3/8 in.)

4 of 9

Inv. 8502

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

The Triumph of Cosimo I at Montemurlo

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over traces of black chalk, heightened with white gouache, lightly squared in black chalk, on faded blue paper

392 x 271 mm (15 7/16 x 10 11/16 in.)

Inv. 1186

Giorgio Vasari AREZZO 1511–1574 FLORENCE

Study for a Ceiling Dedicated to Saturn

Pen and brown ink, light brown wash, over black chalk

376 x 402 mm (14 13/16 x 15 13/16 in.)

Inv. 7

Vincenzo Borghini FLORENCE 1515–1580 FLORENCE

Study for the Wainscot of the West Wall in the Salone dei Cinquecento

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk

234 x 348 mm (9 3/16 x 13 11/16 in.)

Inv. 119

Vincenzo Borghini FLORENCE 1515–1580 FLORENCE

Study of a Fountain

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over traces of black chalk

240 x 263 mm (9 7/16 x 10 3/8 in.)

Inv. 1611

Cristoforo Gherardi BORGO SAN SANSEPOLCRO 1508–1556 FLORENCE

Vulcan’s Forge

Pen and brown ink, brown wash

229 x 414 mm (9 x 16 5/6 in.)

Inv. 760

Giovanni Stradanus (Jan van der Straet) BRUGES 1523–1605 FLORENCE

The Triumph of the Florentine Army After Taking Siena

Pen and brown ink, brown and gray wash, over traces of black chalk

345 x 345 mm (13 9/16 x 13 9/16 in.)

Inv. 657

Giovanni Stradanus (Jan van der Straet) BRUGES 1523–1605 FLORENCE

The Capture of Vicopisano

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white gouache, on faded blue paper

377 x 185 mm (14 13/16 x 7 1/4 in.)

Inv. 1184

Giovanni Stradanus (Jan van der Straet) BRUGES 1523–1605 FLORENCE

The Fox and Hare Hunt

Pen and brown ink, with traces of white heightening

Inscribed at lower left, Della Strada/ inventor 1567

242 x 382 mm (9 1/2 x 15 in.)

Inv. 2347

Giovanni Stradanus (Jan van der Straet) BRUGES 1523–1605 FLORENCE

The Ship of Religion Guided by the Holy Spirit

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white gouache, over traces of black chalk, on paper tinted (?) with ochre

243 x 355 mm (9 5/8 x 14 in.)

Inv. 1082 S

5 of 9

Marco Marchetti da Faenza FAENZA ca. 1526/27–1588 FAENZA

Wall Decoration with the Medici Coat of Arms

Pen and brown ink, brown wash

217 x 308 mm (8 9/16 x 12 1/8 in.)

Inv. 95

Girolamo Macchietti FLORENCE 1535–1592 FLORENCE

The Adoration of the Magi

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk, heightened with white gouache, on faded blue paper

263 x 216 mm (10 3/8 x 8 1/2 in.)

Inv. 1087

Girolamo Macchietti FLORENCE 1535–1592 FLORENCE

Head of a Young Man

Red chalk, red wash

284 x 206 mm (11 3/16 x 8 1/8 in.)

Inv. 7288

Giovan Battista Naldini FLORENCE 1537–1591 FLORENCE

A Satyr Holding a Bunch of Grapes

Black chalk, stumped, heightened with white gouache

412 x 245 mm (16 1/4 x 9 5/8 in.)

Inv. 17175

Giovan Battista Naldini FLORENCE 1537–1591 FLORENCE

Naval Battle

Black chalk, stumped, with traces of heightening in white gouache, on greenish blue paper

258 x 415 mm (10 3/16 x 16 5/16 in.)

Inv. 16501

Jacopo Zucchi FLORENCE ca.1540–1596 ROME

Allegory of the City of Pistoia

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white gouache, on paper tinted blue

212 x 212 mm (8 3/8 x 8 3/8 in.)

Inv. 1491

Friedrich Sustris PADUA ca. 1540–1599 MUNICH

The Triumph of Giuliano dei Medici

Pen and brown ink, light brown and gray wash, over black chalk; squared in black chalk

318 x 385 mm (12 1/2 x 15 3/16 in.)

Inv. 592

The Artists of the Studiolo

Carlo Portelli LORO CIUFFENNA before 1510–1574 FLORENCE

The Family of Darius Before Alexander

Pen and brown ink, with light brown wash, over black chalk

328 x 218 mm (12 15/16 x 8 9/16 in.)

Inv. 1482

Carlo Portelli LORO CIUFFENNA before 1510–1574 FLORENCE

Two Standing Figures, One Holding a Pitcher

Brush and light brown wash, over black chalk

330 x 217 mm (3 x 8 9/16 in.)

Inv. 12137

Jacopo Coppi (Jacopo del Meglio) 1523–1591

Women in a Landscape with the Allegory of a River

6 of 9

Pen and brown ink, with brown wash, over black chalk

246 x 382 mm (9 11/16 x 15 1/16)

Inv. 15556

Giovanni Stradanus (Jan van der Straet) BRUGES 1523–1605 FLORENCE

The Banquet of King Cyrus the Great

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white gouache, on paper tinted brown

292 x 644 mm (11 1/2 x 25 3/8 in.)

Inv. 2341

Giovanni Stradanus (Jan van der Straet) BRUGES 1523–1605 FLORENCE

Allegory of the Immortality of Poetry

Black chalk, pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white gouache, on paper tinted ochre; the figure of Time inserted on a separate piece of paper

Inscribed at lower right, Gio. Stradanu . . . faciebat 1585

469 x 344 mm (18 1/2 x 13 1/2 in.)

Inv. 544 S (and 825 E)

Maso da San Friano (Tommaso Manzuoli) FLORENCE 1531–1571 FLORENCE

An Angel in Flight and Separate Studies of Arms and a Head

Black chalk, gray wash, heightened with white gouache, on darkened blue paper

206 x 313 mm (8 1/8 x 12 5/16 in.)

Inv. 6466

Maso da San Friano (Tommaso Manzuoli) FLORENCE 1531–1571 FLORENCE

The Three Marys at the Tomb

Pen and brown ink and wash, over black chalk

184 x 311 mm (7 1/4 x 12 1/4 in.)

Inscribed at lower left, in pen and brown ink, Tommaso.

Inv. 7277

Maso da San Friano (Tommaso Manzuoli) FLORENCE 1531–1571 FLORENCE

The Risen Christ

Black chalk, with gray wash, on paper tinted gray

237 x 181 (9 5/16 x 7 1/8 in.)

Inscribed at lower left, in pen and brown ink, Tomso Manzuoli.

Inv. 7283

Maso da San Friano (Tommaso Manzuoli) FLORENCE 1531–1571 FLORENCE

Two Nude Children and a Dog

Black chalk, with gray wash, traces of white heightening, on blue-gray paper

254 x 295 mm (10 x 11 5/8 in.)

Inv. 1822 S

Girolamo Macchietti FLORENCE 1535–1592 FLORENCE

Male Nude Seen from Behind

Red chalk, with red wash, heightened with white, on paper tinted red

295 x 208 mm (11 5/8 x 8 3/16 in.)

Inv. 17585

Alessandro Allori FLORENCE 1535–1607 FLORENCE

Studies for a Man with a Naked Torso Holding a Sword

Black chalk, with touches of wash

430 x 278 mm (16 15/16 x 10 15/16 in.)

Inv. 10253

Alessandro Allori FLORENCE 1535–1607 FLORENCE

Study of a Pitcher

Black chalk, with brown wash

7 of 9

440 x 249 mm (17 5/16 x 9 13/16 in.)

Inv. 716

Alessandro Allori FLORENCE 1535–1607 FLORENCE

Seated Male Nude with Raised Right Arm

Black chalk, with touches of wash, heightened with white chalk, on paper tinted light brown

436 x 312 mm (17 3/16 x 12 1/4 in.)

Inv. 10206

Alessandro Allori FLORENCE 1535–1607 FLORENCE

Half-Length Male Portrait

Black chalk, stumped

363 x 258 mm (14 5/16 x 10 3/16 in.)

Inv. 18486

Bibliography: Petrioli Tofani 2002, p. 34.

Alessandro Allori FLORENCE 1535–1607 FLORENCE

The Triumph of Bacchus

Black chalk, pen and brown ink, with brown-gray wash, heightened with white gouache, on paper tinted light brown; squared in red chalk

281 x 471 mm (11 1/6 x 18 9/16 in.)

Inv. 740

Santi di Tito SANSEPOLCRO 1536–1603 FLORENCE

The Crossing of the Red Sea and a Study of Drapery

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over traces of black chalk, over a drapery study in red chalk, on faded blue paper

269 x 204 mm (10 9/16 x 8 in.)

Inv. 2003 S

Santi di Tito SANSEPOLCRO 1536–1603 FLORENCE

Studies of the Head, the Face, and the Bust of a Child

Red chalk, stumped

163 x 213 mm (6 7/16 x 8 3/8 in.)

Inv. 16320

Santi di Tito SANSEPOLCRO 1536–1603 FLORENCE

Solomon Building the Temple of Jerusalem

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk, heightened with white gouache, on faded blue paper; squared in black chalk

272 x 227 mm (10 11/16 x 8 15/16 in.)

Inv. 752

Santi di Tito SANSEPOLCRO 1536–1603 FLORENCE

Male Nude

Black chalk, stumped, with traces of white chalk, on blue paper

397 x 248 mm (15 5/8 x 9 3/4 in.)

Inv. 16326

Santi di Tito SANSEPOLCRO 1536–1603 FLORENCE

Battle Scene, Possibly the Victory of Joshua over the Amorites

Verso: Faint Sketch of a Nude Figure

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white gouache, on blue paper; squared in black chalk; verso: black chalk

286 x 217 mm (11 1/4 x 8 9/16 in.)

Inv. 7706

Giovan Battista Naldini FIESOLE 1537–1591 FLORENCE

Furius Camillus Punishes the Treacherous Schoolmaster of Falerii

Red chalk, stumped, heightened with white gouache

397 x 267 mm (15 5/8 x 10 1/2 in.)

Inv. 14609

Giovan Battista Naldini FIESOLE 1537–1591 FLORENCE

Head of a Youth Turned to the Left

Black and red chalk, heightened with white gouache

277 x 193 mm (10 15/16 x 7 5/8 in.)

Inv. 1965 S

Giovan Battista Naldini FIESOLE 1537–1591 FLORENCE

Seated Male Nude

Verso: Study of Legs

Black chalk, stumped, heightened with white gouache, on blue paper

267 x 180 mm (10 1/2 x 7 1/16 in.)

Inv. 6540

Jacopo Zucchi FLORENCE ca.1540–1596 ROME

Studies of Decorative Elements (recto and verso)

Pen and brown ink, with brown wash; verso: black chalk, pen and brown ink, with light brown wash

340 x 252 mm (13 3/8 x 9 15/16 in.)

Giovanni Maria Butteri FLORENCE ca.1540–1606 FLORENCE

Allegory of the River Mugnone

Verso: Allegory of the River Arno

Black chalk, stumped, squared in black chalk; verso: black chalk

149 x 230 mm (5 7/8 x 9 1/16 in.)

Inv. 7260

Poppi (Francesco Morandini) POPPI 1544–1597 FLORENCE

Two Nude Figures Fighting

Black chalk, stumped, heightened with white chalk, on blue paper

277 x 192 mm (10 15/16 x 7 9/16 in.)

Inv. 1797

Poppi (Francesco Morandini) POPPI 1544–1597 FLORENCE

The Punishment of Titius

Black chalk

221 x 339 mm (8 11/16 x 13 3/8 in.)

Inv. 248

Poppi (Francesco Morandini) POPPI 1544–1597 FLORENCE

Composition with Copies of Sculptural Models

Black chalk, with gray wash

148 x 105 mm (5 13/16 x 4 1/8 in.)

Inv. 4274

Poppi (Francesco Morandini) POPPI 1544–1597 FLORENCE

Four Heads

Black chalk, with gray wash

142 x 96 mm (5 9/16 x 3 3/4 in.)

Inv. 4257 F

.jpg!Large.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/703px-Rembrandt_Harmensz._van_Rijn_-_Christ_Crucified_Between_the_Two_Thieves_(%22The_Three_Crosses%22)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)